[1/31/22 Update]: Looking for something a little more recent? Check out my 2021 edition of this list

More ramblings: if one novel isn’t enough for you, you can also find my 2017, 2016, 2015, and 2014 lists.

Podcast: you can listen to my flat Top 10 list on The Spoiler Warning.

[Cross-posted to Medium]

Introduction

The enterprise of list-making is a doomed one from the start. Art doesn’t adhere to an objective value metric—or even a stable subjective metric—and

even if it did it wouldn’t be transitive (A > B and B > C != A > C), and even if it were it would profoundly miss the point.

It’s why it’s valid to critique awards shows on the basis of inclusion; why rebuttals about “meritocracies” feel childish to

anyone with a passion for the craft. What are the four best ingredients in food? Your top two family members? The nations of the world ranked 195 to 1?

You might notice the most avid fans of a thing are often the least likely to give blanket recommendations—not because they’ve forgotten

how to love, but because they’ve learned to savor the million forms love takes. They know there’s space on the shelf for both triple and session;

that it’s valid to wax poetic about a bretty saison before cheerfully ordering a pilsner.

Great is all around us; the only question is you. What are you in the mood for? What are you looking to fill?

You’ve heard it a thousand times, but that doesn’t make it less true: art isn’t a monologue, it’s an active conversation.

Nowhere is that more apparent than in the universe of film. The time and place in which I enter a movie informs it almost as

much as the content itself: what’s corny in my living room becomes heartbreaking on a red-eye; what’s obvious one year becomes vital in the next.

For those fleeting aspects (mood, location, the insufferable teenagers next to me) I do my best to compensate, but for the

long-lived ones it’d be hollow to try—you can’t sift out context.

Cinema is a response to the world as is, and a breathless provocation for us to respond in kind. Sorry To Bother You is undoubtedly political, but so

are Aquaman, Blockers, and Paddington 2. If not in the editing room, certainly in the multiplex: the moment they opened the doors and let us in,

all of our baggage became a part of the narrative.

So what baggage were we bringing to the theatres last year? Plenty, to be sure: anger in droves, hope a bit less than usual, cynicism,

desperation, exasperation and then some. But if I could find a catch-all description of the prevailing sensation, it would be trauma:

individuals exposing it, society wrestling with it. If 2017 was foggy from a whiplash-induced daze, 2018 was a conscious attempt towards action and response.

Social movements like Times Up forced us to reckon with past injustices; others like Black Lives Matter continued to shine a spotlight on the present.

Parkland students used their trauma as a catalyst for change, while abuse victims relived theirs to bring powerful men to account. Sometimes this yielded legal

results (Weinstein, Cosby, and Spacey each in various stages of prosecution), but more often it provoked some national reckoning: what will we permit, what

will we believe, what right do we have to intentionally forget?

We listened to their stories and tried to internalize their pain; we grappled with

supposed redemption arcs,

re-examined past figures we’d let too easily off the hook.

Both the most discussed comedy special and the Grammy winning song were explicitly about deconstructing trauma and society’s response.

A far cry from strawberry champagne on ice.

I won’t speak for anyone else, but I felt drained by 2018.

I’d wanted to be the sort of person who could absorb all that suffering: to mourn every tragedy from Pittsburgh to Puerto Rico, disown every abuser,

voice outrage at every national sin.

But as the headlines kept coming, my anger felt impotent; my sadness turned hoarse and performative. What was I supposed to do with

all that heaviness? Should I hide behind layers of protective abstraction: ignore it, rationalize it, quarantine it from the heart?

Should I shout back in defiance, or use it as fuel: take some step to redeem it, or turn it into art?

Or should I let the sadness be the thing in itself: seek to understand it, internalize it, commune and move on?

When coming up with a theme for this Best Of list, I wanted let that question guide me: “what do we do with past and present trauma?”

And so, in a classic case of biting off more than I can chew, I’ve compiled a dozen answers to that question—and with each

a pair of excellent films that explore it from a different angle.

While I’m happy to stand by this as a Top 24, the pairing constraint involves a handful of sacrifices1—some films fell lower on the list

than I’d have placed them alone, others made absent entirely.

With that said, the order is still important to me, reflecting both my love for each individual title and the weight their combined message carries.

The lower the number the higher my “score”, with the second in the pair typically rating higher than the

first. But, again, there’s no use in stack-ranking art.2

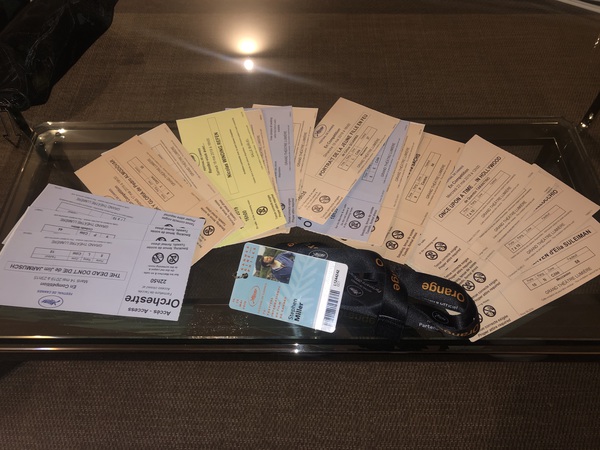

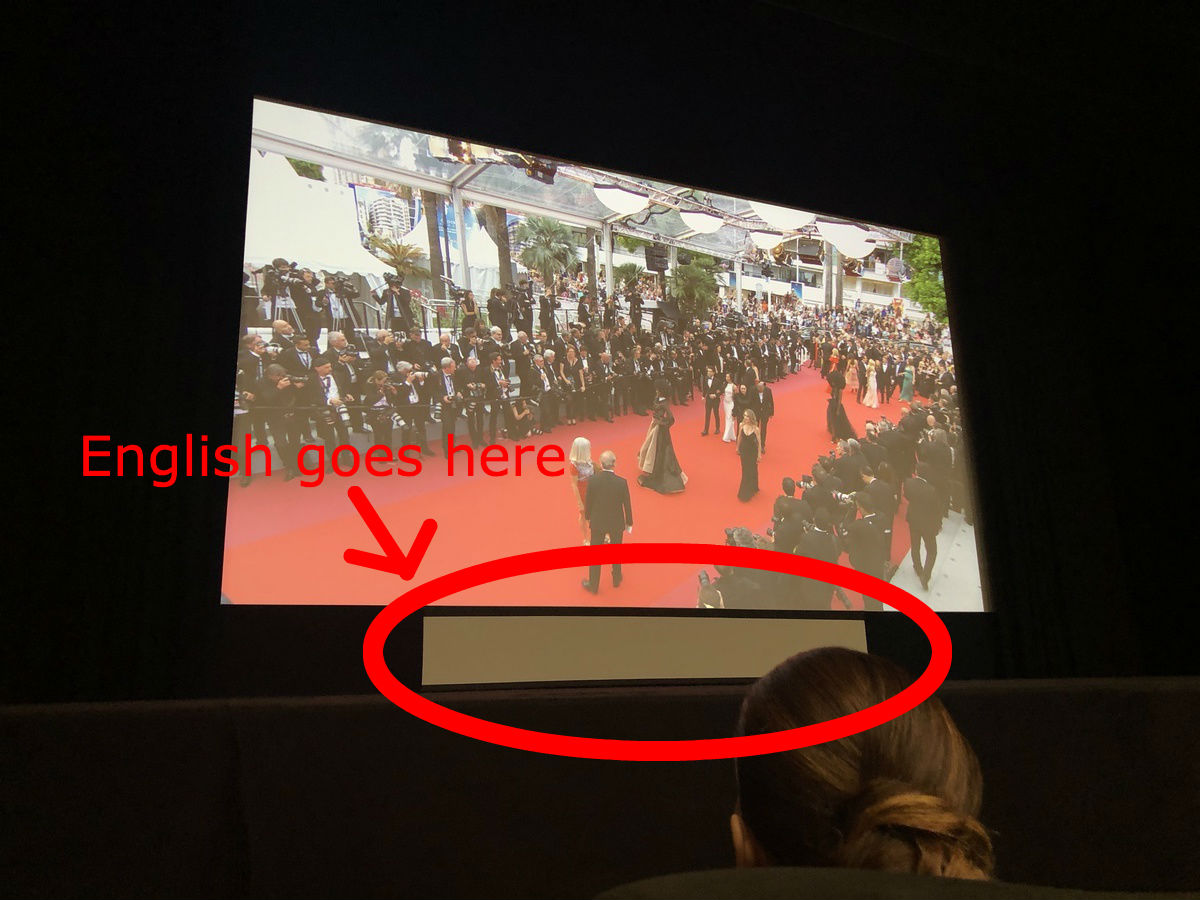

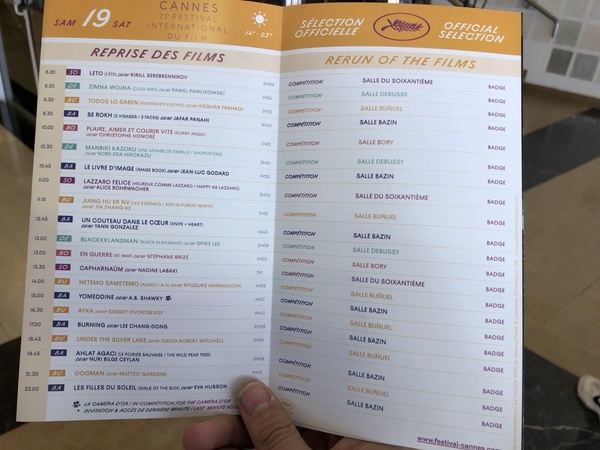

P.S. The standard convention is to hold off on festival screenings till their official release, such that

certain Cannes or Tribeca films should technically fall under 2019. I mostly held to that…except, of

course, when I didn’t, for reasons that are boring and arbitrary.

P.P.S. In 2018 I saw about 120 movies, but there are still bound to be blind spots. Offhand, I know I missed: At Eternity’s Gate,

Zama, Happy As Lazaro, Hale County This Morning This Evening, Border, Hereditary, The Old Man And The Gun, The Mule.

There are also a few I’d hoped to revisit before making this list, given how beloved they seem to be relative

to my (mostly positive!) response: Burning, The Favourite, Cold War, First Reformed.

Enough prologue. How ought we respond to the trauma of this world? We can…

- Quarantine it: Isle of Dogs & Leave No Trace ↯

- Redeem it: Bad Times at the El Royale & The Ballad of Buster Scruggs ↯

- Gild it: Madeline’s Madeline & The Wild Pear Tree ↯

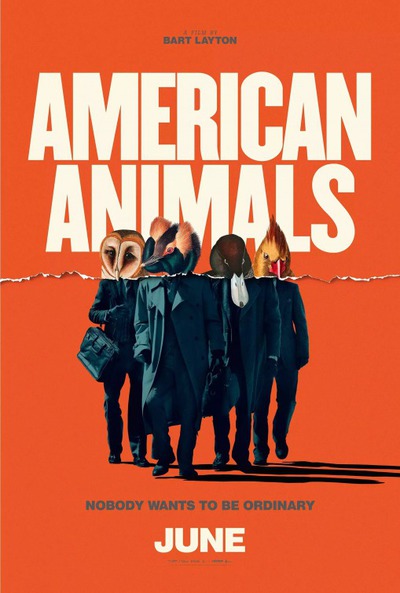

- Rationalize it: American Animals & Thoroughbreds ↯

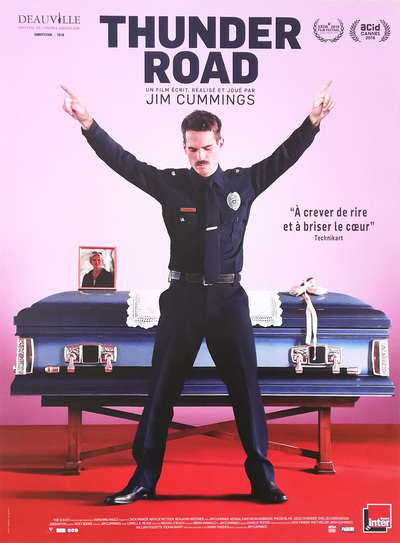

- Thaw it: Thunder Road & State Like Sleep ↯

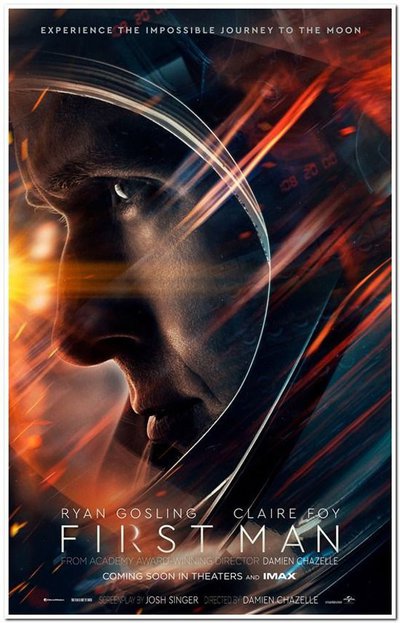

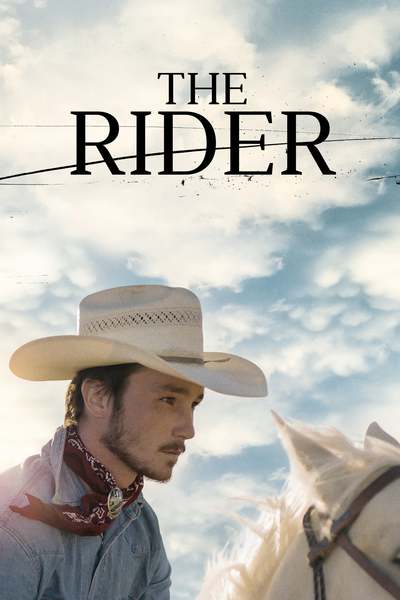

- Outrun it: First Man & The Rider ↯

- Defy it: Support the Girls & Widows ↯

- Expose it: The Tale & BlacKkKlansman ↯

- Reconcile it: Wildlife & Roma ↯

- Share it: Shoplifters & Private Life ↯

- Ameliorate it: Won’t You Be My Neighbor & Eighth Grade ↯

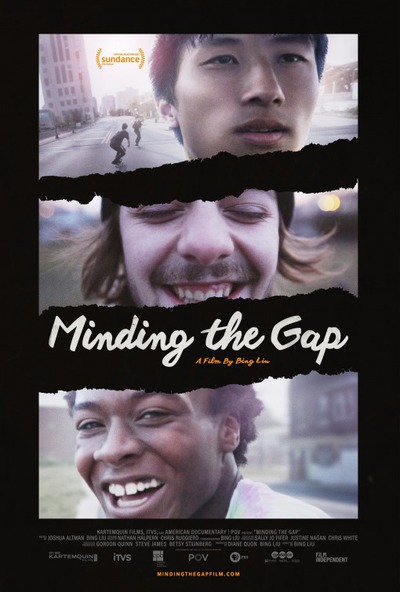

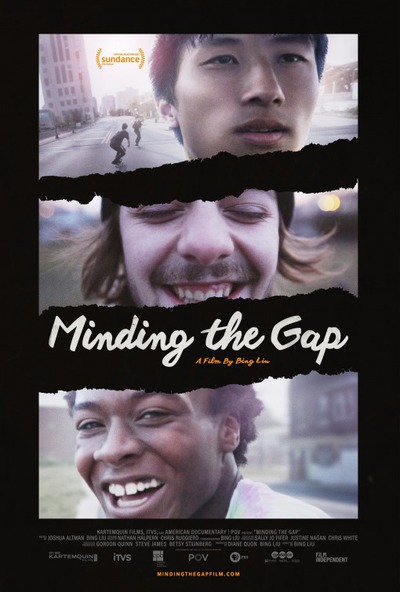

- Unravel it: Blindspotting & Minding the Gap ↯

- Plus some honorable mentions ↯

You know the feeling: you open your news feed after a hellish week, see something terrible, and feel the sudden desire to retreat.

You know it matters, know you have some civic duty to confront it head-on. But you know other things, too: that you’re goddamn

tired; that it’s always something, isn’t it; that nothing anybody does seems to make a dent anyway so why expend the energy.

Wouldn’t it be easier to tamp the bad feelings down? To give yourself permission to look away?

Isle of Dogs is a parable about multiple levels of retreat, beginning with the collective one of the city of Megasaki.

When rapid industrial growth causes an influx in environmental waste, they opt for an S.E.P.

solution. Solving it may be hard, but shoving the problem somewhere else? That one’s easy.

And when the city’s dogs are stricken with disease, they repeat in kind: don’t cure them,

don’t empathize them, simply move their pain out of sight.

Better yet, kill two birds with one stone; and so, dogs roam freely on the ruins of Trash Island.

Political analogs, of course, abound (refugee crises, climate change, our present rhetoric around immigration).

But what truly resonates with me is its sense of personal retreat, in the behavior of dogs who were abandoned.

Chief (Bryan Cranston) has experienced too much heartlessness to hope for anything better. Rather than fight it, he responds in kind.

He cuts off all feelings for Dog’s Best Friend, opting instead to be an island unto himself.

“I bite,” he says bluntly, and it isn’t a warning. It’s an act of resignation.

But through Anderson & Co’s magnificent visual design, we see in his eyes that hope isn’t lost.

Can he get off this literal and figurative wasteland? Can the people of Megasaki swim to meet him halfway?

Isle of Dogs is a parable about multiple levels of retreat, beginning with the collective one of the city of Megasaki.

When rapid industrial growth causes an influx in environmental waste, they opt for an S.E.P.

solution. Solving it may be hard, but shoving the problem somewhere else? That one’s easy.

And when the city’s dogs are stricken with disease, they repeat in kind: don’t cure them,

don’t empathize them, simply move their pain out of sight.

Better yet, kill two birds with one stone; and so, dogs roam freely on the ruins of Trash Island.

Political analogs, of course, abound (refugee crises, climate change, our present rhetoric around immigration).

But what truly resonates with me is its sense of personal retreat, in the behavior of dogs who were abandoned.

Chief (Bryan Cranston) has experienced too much heartlessness to hope for anything better. Rather than fight it, he responds in kind.

He cuts off all feelings for Dog’s Best Friend, opting instead to be an island unto himself.

“I bite,” he says bluntly, and it isn’t a warning. It’s an act of resignation.

But through Anderson & Co’s magnificent visual design, we see in his eyes that hope isn’t lost.

Can he get off this literal and figurative wasteland? Can the people of Megasaki swim to meet him halfway?

Sometimes emotional retreat doesn’t call for hardening; sometimes it simply calls for solitude. In Leave No Trace, Debra Granik delicately

prods at the cons and pros of this choice: the pain of isolation vs the relief of no longer being seen.

Will (Ben Foster) is a widower and a veteran, borne witness to trauma we’re only obliquely privy to.

He has concluded this world is simply too much to bear, opting instead for a makeshift life in the woods.

He and his daughter Tom (Thomasin McKenzie) fashion their own universe:

an ad hoc curriculum of library books and survival guides, a language of signals only they can understand.

For Will, this setup is perfect—provided they don’t get caught. For Tom it’s more complicated: without the catalyst of trauma, she also lacks

his will to isolate. She has physical needs to be “of this world”, but she has other, deeper, emotional needs. She can’t live

life solely as an observer. As they fumble to find balance between those two poles, we see glimmers of human connection: one scene in particular,

involving an animal training class, is among the warmest and most emotionally gratifying of the year.

But warmth and numbness can’t easily coexist, and Granik resists the urge to put a finger on the scales.

She suggests vulnerability isn’t a path we can all take, or at least not one we have a right to force.

Maybe true openness means respecting others’ need to close: giving what we can, withholding what we must,

and trusting the love we scatter along the trail will be found in due time.

Sometimes emotional retreat doesn’t call for hardening; sometimes it simply calls for solitude. In Leave No Trace, Debra Granik delicately

prods at the cons and pros of this choice: the pain of isolation vs the relief of no longer being seen.

Will (Ben Foster) is a widower and a veteran, borne witness to trauma we’re only obliquely privy to.

He has concluded this world is simply too much to bear, opting instead for a makeshift life in the woods.

He and his daughter Tom (Thomasin McKenzie) fashion their own universe:

an ad hoc curriculum of library books and survival guides, a language of signals only they can understand.

For Will, this setup is perfect—provided they don’t get caught. For Tom it’s more complicated: without the catalyst of trauma, she also lacks

his will to isolate. She has physical needs to be “of this world”, but she has other, deeper, emotional needs. She can’t live

life solely as an observer. As they fumble to find balance between those two poles, we see glimmers of human connection: one scene in particular,

involving an animal training class, is among the warmest and most emotionally gratifying of the year.

But warmth and numbness can’t easily coexist, and Granik resists the urge to put a finger on the scales.

She suggests vulnerability isn’t a path we can all take, or at least not one we have a right to force.

Maybe true openness means respecting others’ need to close: giving what we can, withholding what we must,

and trusting the love we scatter along the trail will be found in due time.

Closing may work when the problem is external, but what if the trauma comes from within? Your own past sins, your present demons?

There’s no running from the wrong we inflict on ourselves. We either dig in our feet and declare it a right, or we orient it toward

some arc of redemption. Two films this year, both antihero-brimming period pieces, highlight the allure of that arc—and the difficulty of tracing it.

In Drew Goddard’s Bad Times At The El Royale, our leads find themselves in the same run-down motel on the same stormy night,

at the border between California and Nevada.

There’s Jeff Bridges’ heavy-drinking priest, whose kind eyes and courteous demeanor only betray the regret

they were cultivated to hide. There’s Dakota Johnson’s Emily, the brash enigma whose poker face is only slightly more convincing.

She’s seeking redemption as well; not only for the things she’s done that need salvation, but the things she’s prepared to do to save someone else.

Cynthia Erivo’s Darlene is haunted, but not by regret; she’s living to redeem a past she couldn’t control.

Others too, who won’t be named—each tenant trying to rectify the person they’ve become

with the person they’d hoped to be. To cross some spiritual line, where the light is more flattering or the

provisions more substantial, where the rooms aren’t so achingly sparse.

Everyone, that is, but Chris Hemsworth’s Billy, a Manson-esque figure whose chilly certainty offers a different sort of

comfort: a sturdy logical formula that rounds “regret” down to “none”. He does his damndest to wreak havoc on the Royale.

But neither logic nor plan nor performative confession, can drown out that voice inside. Her song echoes through darkness in defiance of easy answers.

“Love don’t come easy, it’s a game of give and take.”

In Drew Goddard’s Bad Times At The El Royale, our leads find themselves in the same run-down motel on the same stormy night,

at the border between California and Nevada.

There’s Jeff Bridges’ heavy-drinking priest, whose kind eyes and courteous demeanor only betray the regret

they were cultivated to hide. There’s Dakota Johnson’s Emily, the brash enigma whose poker face is only slightly more convincing.

She’s seeking redemption as well; not only for the things she’s done that need salvation, but the things she’s prepared to do to save someone else.

Cynthia Erivo’s Darlene is haunted, but not by regret; she’s living to redeem a past she couldn’t control.

Others too, who won’t be named—each tenant trying to rectify the person they’ve become

with the person they’d hoped to be. To cross some spiritual line, where the light is more flattering or the

provisions more substantial, where the rooms aren’t so achingly sparse.

Everyone, that is, but Chris Hemsworth’s Billy, a Manson-esque figure whose chilly certainty offers a different sort of

comfort: a sturdy logical formula that rounds “regret” down to “none”. He does his damndest to wreak havoc on the Royale.

But neither logic nor plan nor performative confession, can drown out that voice inside. Her song echoes through darkness in defiance of easy answers.

“Love don’t come easy, it’s a game of give and take.”

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is singing different variations on that tune.

Every piece of the Coen’s six-part anthology involves someone trying to

turn the wagon around: searching for some action that can enshrine their misdeeds in glory, recast their brutal existance

as part of a meaningful whole.

And in typical Coen spirit, it definitely don’t come easy—in those rare cases where it comes at all.

It’s a film about characters who hope to become more than characters, who ask for more than the cards they’ve been dealt.

Can Tim Blake Nelson’s Buster be immortalized in death?

Can James Franco’s outlaw find beauty in his fate?

Can Harry Melling’s Artist evangelize softness to a hardened world?

Can Liam Neeson’s Impresario use his calloused hands in service thereof?

Can Tom Waits’ Prospector find the one thing that will justify his endless digging?

Can Zoe Kazan’s Alice conjure unlikely love amid cruelty and death?

Can our stage coach passengers, by some trick of the light, spin their selfish narratives into something fundamentally good?

And is there any use in trying if the outcome stays the same?

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is singing different variations on that tune.

Every piece of the Coen’s six-part anthology involves someone trying to

turn the wagon around: searching for some action that can enshrine their misdeeds in glory, recast their brutal existance

as part of a meaningful whole.

And in typical Coen spirit, it definitely don’t come easy—in those rare cases where it comes at all.

It’s a film about characters who hope to become more than characters, who ask for more than the cards they’ve been dealt.

Can Tim Blake Nelson’s Buster be immortalized in death?

Can James Franco’s outlaw find beauty in his fate?

Can Harry Melling’s Artist evangelize softness to a hardened world?

Can Liam Neeson’s Impresario use his calloused hands in service thereof?

Can Tom Waits’ Prospector find the one thing that will justify his endless digging?

Can Zoe Kazan’s Alice conjure unlikely love amid cruelty and death?

Can our stage coach passengers, by some trick of the light, spin their selfish narratives into something fundamentally good?

And is there any use in trying if the outcome stays the same?

Let’s consider the Artist from above. Unlike other members of the Coen-verse, he offers a different sort of

redemption: no behavior changed, no triumph sought. He promises instead to render an ugly world beautiful.

And isn’t that the allure of art? The chance to alchemize suffering, to put it in service to something greater than itself?

At its best, art becomes a balm for our pain. But, like all numbing agents, it can also be addictive.

Two dreamlike films explore that pull: the beauty it promises and the obsession it demands.

In Josephine Decker’s feverish Madeline’s Madeline, the causal relationship between art and suffering is blurry from the start.

Evangeline (Molly Parker) is an experimental playwright dedicated to finding honesty in art.

And she sees in Madeline (Helena Howard) her ultimate muse: someone who can not only mine her own pain for beauty,

but mine it to seemingly inexhaustible extremes. She doesn’t just emote, she inhabits her art. She becomes whatever she is asked

to reflect: a cat, a monster, a disapproving mother, a dazzling prodigy or a hopeless problem child.

And her powers are as mesmerizing as they are terrifying.

Games become nightmares; warm-up exercises topple into fiery exorcisms. Madeline’s mother (Miranda July) had hoped

the theatre would act as therapy, as a way of releasing Madeline’s anger. But supply-side economics suggests a dual force:

the more her anger’s release is praised, the more she must produce to maintain it. With its towering performances and

dizzying visual language, the film

thrusts us into a similarly dissonant headspace. What is the line between supporter and vouyer?

Is Madeline’s suffering building to catharsis or doubling down on itself, a fractal that emboldens

the very pain it reflects? Can the labyrinth of the heart never be fully exhumed? Or by burrowing into her darkness,

might we eventually hit sky?

In Josephine Decker’s feverish Madeline’s Madeline, the causal relationship between art and suffering is blurry from the start.

Evangeline (Molly Parker) is an experimental playwright dedicated to finding honesty in art.

And she sees in Madeline (Helena Howard) her ultimate muse: someone who can not only mine her own pain for beauty,

but mine it to seemingly inexhaustible extremes. She doesn’t just emote, she inhabits her art. She becomes whatever she is asked

to reflect: a cat, a monster, a disapproving mother, a dazzling prodigy or a hopeless problem child.

And her powers are as mesmerizing as they are terrifying.

Games become nightmares; warm-up exercises topple into fiery exorcisms. Madeline’s mother (Miranda July) had hoped

the theatre would act as therapy, as a way of releasing Madeline’s anger. But supply-side economics suggests a dual force:

the more her anger’s release is praised, the more she must produce to maintain it. With its towering performances and

dizzying visual language, the film

thrusts us into a similarly dissonant headspace. What is the line between supporter and vouyer?

Is Madeline’s suffering building to catharsis or doubling down on itself, a fractal that emboldens

the very pain it reflects? Can the labyrinth of the heart never be fully exhumed? Or by burrowing into her darkness,

might we eventually hit sky?

In The Wild Pear Tree (full review), art is less an exorcism

of pain than it is a way of giving meaning to numb routine. Sinan (Dogu Demirkol) is a young novelist looking to carve out a life for himself.

Fresh out of college but not yet employed, he’s in that transitory phase where everything is amplified to its most romantic extreme.

He doesn’t know what exactly he’s writing, but he knows it needs to bleed; to inhabit all genres, to be about nothing and everything.

Thus he frames integrity as an impossible virtue, a standard failed by quite literally everyone: his mother whose love feels too obvious, uncritical;

his father whose curiosity is neutered by a failure of perseverance; the imams whose faiths seem either hand-wavey or stubborn;

the novelist whose fame was borne of pragmatic compromise. Sinan wants to live on as something pure and revered,

but in his draconian search for purity he’s ruled out the living part. Director Nuri Bilge Ceylan knows this is untenable, of course.

But like Chekhov to his Konstantin or Linklater to his Jesse, there’s a tenderness in this portrait of brash, young idealism.

Sinan may never create a work that perfectly encapsulates both the blandness and beauty of the artistic struggle.

But over three meditative hours of fluid conversation, Ceylan gets extraordinarily close.

In The Wild Pear Tree (full review), art is less an exorcism

of pain than it is a way of giving meaning to numb routine. Sinan (Dogu Demirkol) is a young novelist looking to carve out a life for himself.

Fresh out of college but not yet employed, he’s in that transitory phase where everything is amplified to its most romantic extreme.

He doesn’t know what exactly he’s writing, but he knows it needs to bleed; to inhabit all genres, to be about nothing and everything.

Thus he frames integrity as an impossible virtue, a standard failed by quite literally everyone: his mother whose love feels too obvious, uncritical;

his father whose curiosity is neutered by a failure of perseverance; the imams whose faiths seem either hand-wavey or stubborn;

the novelist whose fame was borne of pragmatic compromise. Sinan wants to live on as something pure and revered,

but in his draconian search for purity he’s ruled out the living part. Director Nuri Bilge Ceylan knows this is untenable, of course.

But like Chekhov to his Konstantin or Linklater to his Jesse, there’s a tenderness in this portrait of brash, young idealism.

Sinan may never create a work that perfectly encapsulates both the blandness and beauty of the artistic struggle.

But over three meditative hours of fluid conversation, Ceylan gets extraordinarily close.

When confronted with the messy realities of our world, it’s tempting to try to reign things in to some manageable

shape. To find a framework (logical or narrative) that somehow excuses it, explains it.

To recast its hypocrisies as helpless or inevitable, and reduce our complicity to a rounding error in kind.

Life isn’t fair. It’s a dog-eat-dog world. You can’t save everyone. They’ll spend it on drugs anyway.

The poor will always be with us. Survival of the fittest. It’ll only breed dependence. More forward or die.

We wield absurdity as a hall pass for apathy, faux-certainty a shield against more complicated truths.

And in limited doses, a bit of anaesthesia is fine: we can’t save everyone, life isn’t always fair.

But logical desensitization is a dangerous game. In what follows, we see what happens when it’s

taken to an extreme.

In the corner of Kentucky where our American Animals leads reside, they see neither wrong nor overt injustice. Just a vague sense of futility

and a dictum to move. You might be surprised to learn that this alone—not poverty, not pain, just run-of-the-mill boredom—was enough to

convince a group of 20somethings to commit a heist. Yet that’s exactly what our fictional protagonists (and their documentary counterparts)

resolve to do. They’re going to steal a priceless work of art from the university library, and do so in broad daylight.

Spencer and crew are not naive. They know that theft is wrong even in a vacuum, and that their escalating stakes could get someone

hurt. Know that even if it worked they wouldn’t be any less alone.

But rather than grapple with that reality, they distract themselves with peripheral narrative—how exhilarating such a stunt would feel,

how cinematic it would look. Excuses come easy when mythology has a foothold: no one will get hurt, no one will miss it, if you

really think about it it’s a victimless crime.

Eventually they cease to be agents making a choice; they become actors performing to an audience of none.

As their plan takes form, and that narrative accumulates mass, we start to feel the same blinding pull.

In the corner of Kentucky where our American Animals leads reside, they see neither wrong nor overt injustice. Just a vague sense of futility

and a dictum to move. You might be surprised to learn that this alone—not poverty, not pain, just run-of-the-mill boredom—was enough to

convince a group of 20somethings to commit a heist. Yet that’s exactly what our fictional protagonists (and their documentary counterparts)

resolve to do. They’re going to steal a priceless work of art from the university library, and do so in broad daylight.

Spencer and crew are not naive. They know that theft is wrong even in a vacuum, and that their escalating stakes could get someone

hurt. Know that even if it worked they wouldn’t be any less alone.

But rather than grapple with that reality, they distract themselves with peripheral narrative—how exhilarating such a stunt would feel,

how cinematic it would look. Excuses come easy when mythology has a foothold: no one will get hurt, no one will miss it, if you

really think about it it’s a victimless crime.

Eventually they cease to be agents making a choice; they become actors performing to an audience of none.

As their plan takes form, and that narrative accumulates mass, we start to feel the same blinding pull.

That’s the thing about hypothetical arguments: they have a way of bypassing our built-in quality control. Like the adage about boiling a frog, they begin

as rationale too harmless to refute, but slowly—through a chain of mental escalations, each too subtle to trigger a red flag on its own—they gain substance.

In Thoroughbreds (full review), Lily (Anya Taylor Joy) doesn’t begin as a murderer.

She begins as we all do: young, malcontent, tragically bored. She feels in her bones that life isn’t as it ought to be, and she sees in her stepfather

the apotheosis of that lack. She wishes he weren’t there, would just disappear. She maybe even wishes she could be the one to do it.

But her desires are purely hypothetical—until she tells Amanda. Amanda (Olivia Cooke) is all heart and no head; she is “technically right” incarnate.

I see in her the reductio ad absurdum of countless half-compelling ideologies (you choose the ism: nihil-, determin-, libertarian-, New Athe-).

She speaks with the certainty of someone who has no skin in the game, and her impeccable logic becomes an impenetrable shield.

She doesn’t cause Lily’s anger, of course. She only permits it. “The only thing worse than being incompetent or being unkind or being evil

is being indecisive.” It’s the sort of oversimplified mantra too reductive to be true, but too catchy to shake.

It lodges somewhere inside, gestates. It’s powerful precisely because it’s simple: you can hold it, recite it, surrender yourself to it.

With pitch-black screenplay and two outstanding lead performances, Cory Finley makes that surrender a thrill.

That’s the thing about hypothetical arguments: they have a way of bypassing our built-in quality control. Like the adage about boiling a frog, they begin

as rationale too harmless to refute, but slowly—through a chain of mental escalations, each too subtle to trigger a red flag on its own—they gain substance.

In Thoroughbreds (full review), Lily (Anya Taylor Joy) doesn’t begin as a murderer.

She begins as we all do: young, malcontent, tragically bored. She feels in her bones that life isn’t as it ought to be, and she sees in her stepfather

the apotheosis of that lack. She wishes he weren’t there, would just disappear. She maybe even wishes she could be the one to do it.

But her desires are purely hypothetical—until she tells Amanda. Amanda (Olivia Cooke) is all heart and no head; she is “technically right” incarnate.

I see in her the reductio ad absurdum of countless half-compelling ideologies (you choose the ism: nihil-, determin-, libertarian-, New Athe-).

She speaks with the certainty of someone who has no skin in the game, and her impeccable logic becomes an impenetrable shield.

She doesn’t cause Lily’s anger, of course. She only permits it. “The only thing worse than being incompetent or being unkind or being evil

is being indecisive.” It’s the sort of oversimplified mantra too reductive to be true, but too catchy to shake.

It lodges somewhere inside, gestates. It’s powerful precisely because it’s simple: you can hold it, recite it, surrender yourself to it.

With pitch-black screenplay and two outstanding lead performances, Cory Finley makes that surrender a thrill.

If we sometimes use logic to cauterize suffering, more often than not we settle for numbing it—changing the subject, clinging to some new distraction.

But despite all good intentions, nothing can stay frozen forever. All pent-up grief must eventually thaw. These films express the

way time-delayed sorrow has a way of catching up with us, and the pain inherent in meeting it head-on.

A feature-length addition to his eponymous short, Jim Cummings’ Thunder Road is a tiny miracle: an empathetic character study that is exactly as tone-clashing as grief itself. Effusive tears as prelude to unexpected laughter, a tinge of self-awareness hiding deeper denial. Officer Jim wants to seem like he has it all together:

like the death of his mother didn’t completely unmoor him, like the custody battle for his daughter isn’t always top-of-mind.

But with a knack for saying aloud precisely what he meant hidden, and a camera that rarely leaves the writer-director’s face,

Jim’s vault is about as flimsy as they come. He cracks, and cracks often, with each outburst slightly more heightened than the last.

A humanistic drama anchored around four or five searing long-take monologues,

Cummings’ film is extremely endearing—even as his lead grows increasingly less relatable.

Thunder Road is interested in the peaks of grief and catharsis; in what breaks a man, and what happens next.

He can hide beneath his covers and study his pain, sure, but what happens when there’s nothing left to study?

When the funeral was three weeks back, the world has moved on, and you’ve alienated everyone

you’d meant for support? Eventually it becomes a choice: to roll down the windows if only a crack. To let something in so the stale bits can go.

A game of patty-cake with your smirking daughter. A buddy with a twelve pack and not much to say.

You coast in that gear between collapse and delusion, and hope the shit in your rearview isn’t as forever as it appears.

Accumulate distance, feel the wind in your hair, and you’ll know you’ve finally reached the song’s crescendo.

Sit tight, take hold.

Katherine (Waterston) has accumulated physical distance from trauma, but she’s no closer to that highway than Jim at the start.

It’s been a year since the unexplained death of her husband, and she’s done all she could to drown out the noise:

packed up and moved across the Pacific, thrown every ounce of willpower at her career. But eventually, as always, her old life calls her home.

A neon noir through rainy-night Brussels, Meredith Danluck’s State Like Sleep (full review)

sets off on a search for answers. What led him to die like this? Who’s left to blame? Underground nightclubs and all manner of seedy character await,

cast in a shimmering, sludgy haze. The heart of the film, though, has nothing to do with answers.

It’s about what the search catalyzes inside of Katherine; the feelings she’s exposed to, the shame brought bubbling up.

The way words of comfort from a loved one can serve to amplify that pain; the way the ear of a stranger (Michael Shannon) can prove a safer release.

Anchored by a wonderful lead performance, hypnotic cinematography, and four of the most expressive eyes in Hollywood, State Like Sleep moved me

in a way few did this year. Call it the festival high or nostalgia for a particular time and place: this is one underseen gem I can’t wait to revisit.

Katherine (Waterston) has accumulated physical distance from trauma, but she’s no closer to that highway than Jim at the start.

It’s been a year since the unexplained death of her husband, and she’s done all she could to drown out the noise:

packed up and moved across the Pacific, thrown every ounce of willpower at her career. But eventually, as always, her old life calls her home.

A neon noir through rainy-night Brussels, Meredith Danluck’s State Like Sleep (full review)

sets off on a search for answers. What led him to die like this? Who’s left to blame? Underground nightclubs and all manner of seedy character await,

cast in a shimmering, sludgy haze. The heart of the film, though, has nothing to do with answers.

It’s about what the search catalyzes inside of Katherine; the feelings she’s exposed to, the shame brought bubbling up.

The way words of comfort from a loved one can serve to amplify that pain; the way the ear of a stranger (Michael Shannon) can prove a safer release.

Anchored by a wonderful lead performance, hypnotic cinematography, and four of the most expressive eyes in Hollywood, State Like Sleep moved me

in a way few did this year. Call it the festival high or nostalgia for a particular time and place: this is one underseen gem I can’t wait to revisit.

Numbing mechanisms can take many forms. I find, in my own life, that the most potent distraction can be personal ambition:

letting myself burrow fully into some project or goal, installing blinders against the big picture.

And while I’m sure it’s universal, I feel something distinctly male in the shape my blinders take: the

way The Goal becomes desperate, self-propagating, a bet staked by no one.

Two films’ protagonists face a similar condition; men in the heartland who have become addicted to a dangerous ambition, using it as means to outrun trauma. Or

if nothing else, to move so fast its details blur.

Damien Chazelle is fascinated by ambition and the immolation that comes with it—the drummer tapping till his hands go bloody,

the young lovers who forsake all for their art. Typically that ambition is fueled by a high, some palpable thrill.

In First Man the ambition couldn’t be loftier, or its promise of adoration more pronounced.

But if Gosling’s Neil Armstrong is enjoying his race to the moon, he does little to let us know.

There are no Right Stuff glimmers of fraternity, here, no Apollo 13 break for national applause. If

there’s even a smile, it’s fleeting and thin.

Rather than fixate on the glamour of The Ultimate Goal, Chazelle trains his gaze on the sadness it conceals—the

tragic loss of Armstrong’s daughter, whose tiny absence informs every gesture he makes.

Rather than face that grief, he turns inward, a stone; unable to relate to his wife

(Claire Foy) in her mourning, unable to find joy in the children he’s expected to raise.

Confronted with human loss, he resolves instead to look upward.

And while he might be that impulse’s clearest manifestation, we see in society the same upwards tilt.

Faced with incomprehensible, tangible losses—nuclear annihilation, societal upheaval, civil rights violations, abject poverty—they distract

with the promise of a Sisyphean task. “The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart!”

But perched atop that chilly rock, from the most jaw-dropping heights IMAX can render, should we really imagine Armstrong happy?

Neil may be trying to outrun his sorrow, but he masks it well—behind glory, national unity, inspiration.

In Chloé Zhao’s The Rider, challenge is the sole motivating factor: not because it is easy,

not to stick it to the Soviets, but solely because it is hard. And dangerous. And a hell of a rush.

Brady (Jandreau) has one calling in life: to tame and ride bucking broncos. So when a brain injury threatens

the viability of that calling, he only doubles down. Like Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler, he knows the path he’s chosen is

destructive, perhaps even deadly. But absent that risk, what alternative could he choose?

Days stocking shelves in a sterile grocery aisle, nights shooting shit about “old days” long gone?

No, better to die in motion than live standing still. In the face of First Man, it might seem strange to wax poetic

about the glory of a Midwestern rodeo. But if you’ve seen Zhao’s footage, you’ll know: the moment the gate opens,

those broncos snap loose with a force that rivals any spaceship. She lets us feel, viscerally, just how liberating his escape could be.

The Rider is a soulful parable about restlessness: about the things you would do to drown out the lonely,

and what happens when those same things threaten to destroy you.

Would you choose to go gently into life’s simple pleasures? Or would you strain against the rock till it wins?

Neil may be trying to outrun his sorrow, but he masks it well—behind glory, national unity, inspiration.

In Chloé Zhao’s The Rider, challenge is the sole motivating factor: not because it is easy,

not to stick it to the Soviets, but solely because it is hard. And dangerous. And a hell of a rush.

Brady (Jandreau) has one calling in life: to tame and ride bucking broncos. So when a brain injury threatens

the viability of that calling, he only doubles down. Like Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler, he knows the path he’s chosen is

destructive, perhaps even deadly. But absent that risk, what alternative could he choose?

Days stocking shelves in a sterile grocery aisle, nights shooting shit about “old days” long gone?

No, better to die in motion than live standing still. In the face of First Man, it might seem strange to wax poetic

about the glory of a Midwestern rodeo. But if you’ve seen Zhao’s footage, you’ll know: the moment the gate opens,

those broncos snap loose with a force that rivals any spaceship. She lets us feel, viscerally, just how liberating his escape could be.

The Rider is a soulful parable about restlessness: about the things you would do to drown out the lonely,

and what happens when those same things threaten to destroy you.

Would you choose to go gently into life’s simple pleasures? Or would you strain against the rock till it wins?

Or maybe there’s a third route for both of our heroes; a different sort of irrational joy, no less absurd but a bit less destructive.

A different philosopher put it best:

only one thing

made him happy

and now that

it was gone

everything

made him happy

– Leonard Cohen

Sometimes trauma is too big to outrun; sometimes it’d be short-sighted to try.

From #AbolishICE to #MeToo, we’ve seen there can be immense value in rising up, in challenging

a painful status quo. In setting the cards we’ve been dealt ablaze.

Two films, starring women of color, capture the pressure that leads one to

finally fight back—and the visceral howl it releases.

In Andrew Bujalski’s Support the Girls, the system might strike you as fairly mundane. And Lisa (Regina Hall)

doesn’t initially seem like a woman on the brink. Working a thankless management gig for a local

Breastaurant, she’s accepted that the world won’t change around her.

Like so many unsung heroes of middle-management, she’s resolved instead to act as a buffer:

to do whatever she can within her shitty situation to better the lives of those in her orbit. Like raising

legal fees for her embattled employee Shaina (Jana Kramer), or helping Danyelle (Shanya McHale) recognize

the potential within, or solving one of a thousand little problems through some unseen act of bureaucratic ingenuity.

Over the course of her day, though, a realization dawns on her. This thing she’s so good at, expending

so much energy to hold together…it doesn’t deserve to be held. Her job with the creepy clientele and stapled-on smile,

her coddled boss who wouldn’t recognize competent leadership if it grabbed him by the mullet: it all needs to go. Like Thunder Road, this is another low-budget gem of a character study,

showcasing an individual in a state of emotional flux. But unlike Officer Jim, Lisa is fueled by nothing if not clarity: she demands more out of life than

what she’s been given. As keenly observed as anything in Bujalski’s mumblecore wheelhouse, but with

far more cultural fluency and bite, Support the Girls is a joyous celebration of those who look a broken system in

the eye and say “Not another word.”

In Andrew Bujalski’s Support the Girls, the system might strike you as fairly mundane. And Lisa (Regina Hall)

doesn’t initially seem like a woman on the brink. Working a thankless management gig for a local

Breastaurant, she’s accepted that the world won’t change around her.

Like so many unsung heroes of middle-management, she’s resolved instead to act as a buffer:

to do whatever she can within her shitty situation to better the lives of those in her orbit. Like raising

legal fees for her embattled employee Shaina (Jana Kramer), or helping Danyelle (Shanya McHale) recognize

the potential within, or solving one of a thousand little problems through some unseen act of bureaucratic ingenuity.

Over the course of her day, though, a realization dawns on her. This thing she’s so good at, expending

so much energy to hold together…it doesn’t deserve to be held. Her job with the creepy clientele and stapled-on smile,

her coddled boss who wouldn’t recognize competent leadership if it grabbed him by the mullet: it all needs to go. Like Thunder Road, this is another low-budget gem of a character study,

showcasing an individual in a state of emotional flux. But unlike Officer Jim, Lisa is fueled by nothing if not clarity: she demands more out of life than

what she’s been given. As keenly observed as anything in Bujalski’s mumblecore wheelhouse, but with

far more cultural fluency and bite, Support the Girls is a joyous celebration of those who look a broken system in

the eye and say “Not another word.”

If Support the Girls was all about magnifying tiny injustices, Widows thrives in reining

massive ones in. On the surface, Steve McQueen’s genre flick is a sort of hybrid revenge / heist story:

Veronica (Viola Davis) responding to the death of her husband by taking matters into her own hands.

That narrative is present, of course, and it’s as deliriously fun as you’d expect—not since The Departed have

I seen a crime drama so utterly self-assured, so masterful in its twisty, bloody brooding.

But what truly elevates it is the score of issues it manages to wrestle with on the side; touching on politics and poverty,

the racial dynamics of crime, the way institutions become self-propagating machines with their own language

of loopy self-justification. Like a David Simon show without the didacticism, or Scorcese with added sociopolitical heft,

this is a film that dissects more in the periphery than do most “serious” films up front.

In McQueen’s universe, every individual is lashing out against something:

Viola a loss that runs multiple layers deep, the Manning Brothers (Brian Tyree Henry and Daniel Kaluuya)

a Chicago that walls off legitimate paths to power, Belle (Cynthia Erivo)

a class structure that refuses her a foothold, Alice (Elizabeth Debicki) a world that views her in transactional terms.

Visceral and chilly, a popcorn flick with menace, Widows might not be the root-for-the-winning-team

spectacle its premise implied. It’s something at once more difficult and satisfying: a story of anger seeking an outlet;

of flawed responses to a rot that won’t clear itself out. And it’s absolutely riveting.

If Support the Girls was all about magnifying tiny injustices, Widows thrives in reining

massive ones in. On the surface, Steve McQueen’s genre flick is a sort of hybrid revenge / heist story:

Veronica (Viola Davis) responding to the death of her husband by taking matters into her own hands.

That narrative is present, of course, and it’s as deliriously fun as you’d expect—not since The Departed have

I seen a crime drama so utterly self-assured, so masterful in its twisty, bloody brooding.

But what truly elevates it is the score of issues it manages to wrestle with on the side; touching on politics and poverty,

the racial dynamics of crime, the way institutions become self-propagating machines with their own language

of loopy self-justification. Like a David Simon show without the didacticism, or Scorcese with added sociopolitical heft,

this is a film that dissects more in the periphery than do most “serious” films up front.

In McQueen’s universe, every individual is lashing out against something:

Viola a loss that runs multiple layers deep, the Manning Brothers (Brian Tyree Henry and Daniel Kaluuya)

a Chicago that walls off legitimate paths to power, Belle (Cynthia Erivo)

a class structure that refuses her a foothold, Alice (Elizabeth Debicki) a world that views her in transactional terms.

Visceral and chilly, a popcorn flick with menace, Widows might not be the root-for-the-winning-team

spectacle its premise implied. It’s something at once more difficult and satisfying: a story of anger seeking an outlet;

of flawed responses to a rot that won’t clear itself out. And it’s absolutely riveting.

Sometimes we’re too close to a rotten situation to recognize it for what it is; sometimes the present doesn’t

give us the firepower to fight. Instead we wrap it in protective mythology, using whatever tools we can to survive.

As a frozen grief will eventually thaw, though, so will the stories we build to protect ourselves eventually crumble.

These genre-bending films blur the line between truth and fiction—wielding story as a sledgehammer.

They tear down rosy narratives of the past, and hold the resulting ugliness up the light.

In Jennifer Fox’s autobiographical The Tale, she grapples with the horrors of her own childhood abuse.

Her mother has found an old 8th grade essay, which features a number of troubling references—an “older boyfriend”, a perfect romance.

If she is understandably upset, Jennifer (Laura Dern) is initially dismissive: the past is the past, what’s the use in digging it up?

But dig she does, first out of curiosity,

then necessity. As Fox (the character) attempts to reconcile the world she saw at 13 with reality she knows at 40,

Fox (the director) explores the many contradictions of assault survival: the flimsy rationalizations,

the undeserved shame, the desire to find a framework that renders life “normal”.

She doesn’t just pay lip-service to them; she shows them, using experimental narrative to render inconsistencies on screen.

Her depiction of the past is glossy, but off-putting; part the Virgin Suicides and part The Stories We Tell,

its past-tense actors (a chilling Jason Ritter and an almost otherworldly Elizabeth Debicki) strike me more as symbols than flesh-and-blood people.

Which is fitting, given Fox’s aims: despite its immensely personal aspect, the film is less interested in the

details of her specific trauma than in the overall shape trauma can take; the

way it mutates in the mind, preserves itself behind bulletproof glass.

In her attempt to shatter it, her film gets at horrors too galling to be depicted in any other medium:

too ugly and exploitable to depict in fiction, too devastating to make plain in documentary.

It’s a singular—and fearless—exhumation of trauma.

BlacKkKlansman (full review) also

uses fiction as stepping-stone to real world trauma. But if The Tale uses the present to shine a haunting

light on the past, Spike Lee’s latest uses past to shine a light on the present. On the surface, the film is a 70’s-style

buddy cop flick about past-tense racism: a joint infiltration of the KKK led by a black officer, Ron Stallworth

(John David Washington) and his white partner, Flip (Adam Driver).

But like Fox, Lee’s vision of the past strikes me as too glossy to be literal:

a squad neatly separated into Crooked Cop and Hero, villains so bumbling they border on comedic.

But as his fable grows ever more implausible, hints of the real world continue to peek through.

A speech by Kwame Ture (Corey Hawkins) resounds with modern-day

fire; a viewing of Birth Of A Nation feels palpably Now. While Stallworth debates whether it’s even possible to

change a crooked system from within, for most of the runtime he seems to be doing just that—and doing it effortlessly.

You can almost feel Lee struggling to untangle his dual inspirations,

the rose-tinted past Hollywood sold us and the present-day racism that proves it a lie.

When he finally pulls the rug out from under us, it comes with a jolt I hadn’t experienced since

Do The Right Thing—a searing indictment of our own damning past, and the technicolored fables we use as a figleaf.

BlacKkKlansman (full review) also

uses fiction as stepping-stone to real world trauma. But if The Tale uses the present to shine a haunting

light on the past, Spike Lee’s latest uses past to shine a light on the present. On the surface, the film is a 70’s-style

buddy cop flick about past-tense racism: a joint infiltration of the KKK led by a black officer, Ron Stallworth

(John David Washington) and his white partner, Flip (Adam Driver).

But like Fox, Lee’s vision of the past strikes me as too glossy to be literal:

a squad neatly separated into Crooked Cop and Hero, villains so bumbling they border on comedic.

But as his fable grows ever more implausible, hints of the real world continue to peek through.

A speech by Kwame Ture (Corey Hawkins) resounds with modern-day

fire; a viewing of Birth Of A Nation feels palpably Now. While Stallworth debates whether it’s even possible to

change a crooked system from within, for most of the runtime he seems to be doing just that—and doing it effortlessly.

You can almost feel Lee struggling to untangle his dual inspirations,

the rose-tinted past Hollywood sold us and the present-day racism that proves it a lie.

When he finally pulls the rug out from under us, it comes with a jolt I hadn’t experienced since

Do The Right Thing—a searing indictment of our own damning past, and the technicolored fables we use as a figleaf.

Sometimes history yields a clear hero or villain, but more often than not it’s a vague, messy thing. In these instances,

we look back not so much to challenge our past, as to accept its maddening intractabilities. Two films

this year concern themselves with that clarification process. Both are period pieces which try to reconcile social

asymmetries, relational strife, and the demands of parenthood—as filtered through the eyes of a child.

In Wildlife, we witness the dissolution of Joe’s (Ed Oxenbould’s) family as he might have seen it:

through a camera dimly, vague and inexplicable.

It’s 1960’s Montana, and Jerry Brinston (Jake Gyllenhaal) is yet again down on his luck.

Like so many men this year

(First Man, American Animals, The Rider, Free Solo), he’s compelled by a gnawing sort of ambition.

He’s restless. He needs to do something. To be of some hard, simple, undeniable use.

And so he sets off to fight a wildfire, leaving his wife and son behind.

Said wife, Jeanette (Carey Mulligan), is struggling with her own brand of restlessness. But the flames she’s

drawn to are of a less literal sort. If affair with an older man (Bill Camp) begins as discreet,

it quickly veers towards the performative: unmuffled giggle-fits in the adjacent bedroom,

drunken dinner parties under barely-there pretenses. It’s a strange situation, and neither we nor Joe ever quite have a grip on it.

She hasn’t snapped a la American Beauty, but she’s not quite calm and collected either.

It’s as if she wants her son to see what’s driving her, to peer through her cracks, bear witness to her pain.

Like she’s sending a telegraph to Future Joe that Present Joe can’t read.

While we’re never told this is a retrospective, Paul Dano’s direction lends it the unmistakable cadence of memory.

I can almost feel Joe sitting in his study a few decades (and divorces) later, drinking a glass of wine,

staring at old photographs, and wondering “Where the hell did it all go wrong?”

In Wildlife, we witness the dissolution of Joe’s (Ed Oxenbould’s) family as he might have seen it:

through a camera dimly, vague and inexplicable.

It’s 1960’s Montana, and Jerry Brinston (Jake Gyllenhaal) is yet again down on his luck.

Like so many men this year

(First Man, American Animals, The Rider, Free Solo), he’s compelled by a gnawing sort of ambition.

He’s restless. He needs to do something. To be of some hard, simple, undeniable use.

And so he sets off to fight a wildfire, leaving his wife and son behind.

Said wife, Jeanette (Carey Mulligan), is struggling with her own brand of restlessness. But the flames she’s

drawn to are of a less literal sort. If affair with an older man (Bill Camp) begins as discreet,

it quickly veers towards the performative: unmuffled giggle-fits in the adjacent bedroom,

drunken dinner parties under barely-there pretenses. It’s a strange situation, and neither we nor Joe ever quite have a grip on it.

She hasn’t snapped a la American Beauty, but she’s not quite calm and collected either.

It’s as if she wants her son to see what’s driving her, to peer through her cracks, bear witness to her pain.

Like she’s sending a telegraph to Future Joe that Present Joe can’t read.

While we’re never told this is a retrospective, Paul Dano’s direction lends it the unmistakable cadence of memory.

I can almost feel Joe sitting in his study a few decades (and divorces) later, drinking a glass of wine,

staring at old photographs, and wondering “Where the hell did it all go wrong?”

Whether Joe is looking back is subject to interpretation. With Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, that backward gaze is its

evident beating heart. Set in the early 1970’s in his hometown of Mexico City, the film follows stand-ins for

the two most important women in his young life, each of whom are struggling within their own social caste.

There’s the mother, Sofia (Marina de Tavira), who appears at first blush to be the film’s protagonist.

Much like Jeanette, her husband’s abandonment sends her down a path of liberation—swerving, perhaps, reckless if need be.

But her emotional journey fades to the background as the true lead emerges: Cleo (Yaliza Aparicio),

the family’s longsuffering, loving, endlessly generous housekeeper of indigeneous descent.

For every indignity Sofia suffers, Cleo suffers a thousand in kind. And yet she

never responds with Sofia’s defiance, opting instead for a humble, quiet, nearly angelic perseverance. We can almost feel Cuarón’s conflict

of feeling on screen, as he considers his own mother and his housekeeper Libo. Is it right to cast Libo in this saintly glow,

to treat long-sufferance as a virtue rather than implicate that suffering’s source? Was her unwavering love for him

a thing to be praised, or a societal symptom to be mourned? Was his mother the hero in one story, the villain in another, or some combination?

As we glimpse moments of calm and calamity, tenderness and hardness, symmetric intimacies and asymmetric transactions,

we get no closer to an answer. And maybe there is no answer. Maybe we each contain multitudes, and our best hope is to render them

as faithfully as we can. Painting in gorgeous, panoramic black and white, Cuarón at least makes the mystery shine.

Whether Joe is looking back is subject to interpretation. With Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, that backward gaze is its

evident beating heart. Set in the early 1970’s in his hometown of Mexico City, the film follows stand-ins for

the two most important women in his young life, each of whom are struggling within their own social caste.

There’s the mother, Sofia (Marina de Tavira), who appears at first blush to be the film’s protagonist.

Much like Jeanette, her husband’s abandonment sends her down a path of liberation—swerving, perhaps, reckless if need be.

But her emotional journey fades to the background as the true lead emerges: Cleo (Yaliza Aparicio),

the family’s longsuffering, loving, endlessly generous housekeeper of indigeneous descent.

For every indignity Sofia suffers, Cleo suffers a thousand in kind. And yet she

never responds with Sofia’s defiance, opting instead for a humble, quiet, nearly angelic perseverance. We can almost feel Cuarón’s conflict

of feeling on screen, as he considers his own mother and his housekeeper Libo. Is it right to cast Libo in this saintly glow,

to treat long-sufferance as a virtue rather than implicate that suffering’s source? Was her unwavering love for him

a thing to be praised, or a societal symptom to be mourned? Was his mother the hero in one story, the villain in another, or some combination?

As we glimpse moments of calm and calamity, tenderness and hardness, symmetric intimacies and asymmetric transactions,

we get no closer to an answer. And maybe there is no answer. Maybe we each contain multitudes, and our best hope is to render them

as faithfully as we can. Painting in gorgeous, panoramic black and white, Cuarón at least makes the mystery shine.

If a broken home can be a prism through which we refract the world’s trauma, a loving one can often act as a bulwark.

Two films look at the ephemeral nature of family, and the strength that can come from even its unconventional variants.

When Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Shoplifters (full review)

premiered at Cannes, I was expecting more of his typical fare: searing

family drama with a quiet undercurrent of grief. What I hadn’t expected was how sharply it would probe at the idea of family itself.

For the Shibatas, the familial bond is closer to marriage: a conscious choice to co-identify, co-exist.

To share in sickness and in health, in plenty and especially in want.

In stealing fresh fruit from the neighborhood market, and in warmth underneath a tin-pattering roof.

But who, exactly, gets to make that choice? Hatsue (Kirin Kiki) can choose to be the designated provider; Osamu (Lily Franky)

and Nobuyo (Sakura Ando) co-conspirators in romance. But for Shota (Jyo Kairi), the young boy turned apprentice in theft,

is it fair to say that this life was a choice? What about five-year-old Yuri (Miyu Sasaki), inducted to the Shibata clan at the start of the film

to escape an abusive family of her own? She knows that they love her, and—in the year’s most heartbreaking scene—she learns precisely

how that love is intended to feel. But is she capable of participating in that choice? Is she even aware she’s making one?

Sweet but not saccharine, and human to the core, Shoplifters gives breathing room to all these questions without tipping the scales. In its

delicate stroll between the moral alleyways of life, though, it just might fill your heart.

When Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Shoplifters (full review)

premiered at Cannes, I was expecting more of his typical fare: searing

family drama with a quiet undercurrent of grief. What I hadn’t expected was how sharply it would probe at the idea of family itself.

For the Shibatas, the familial bond is closer to marriage: a conscious choice to co-identify, co-exist.

To share in sickness and in health, in plenty and especially in want.

In stealing fresh fruit from the neighborhood market, and in warmth underneath a tin-pattering roof.

But who, exactly, gets to make that choice? Hatsue (Kirin Kiki) can choose to be the designated provider; Osamu (Lily Franky)

and Nobuyo (Sakura Ando) co-conspirators in romance. But for Shota (Jyo Kairi), the young boy turned apprentice in theft,

is it fair to say that this life was a choice? What about five-year-old Yuri (Miyu Sasaki), inducted to the Shibata clan at the start of the film

to escape an abusive family of her own? She knows that they love her, and—in the year’s most heartbreaking scene—she learns precisely

how that love is intended to feel. But is she capable of participating in that choice? Is she even aware she’s making one?

Sweet but not saccharine, and human to the core, Shoplifters gives breathing room to all these questions without tipping the scales. In its

delicate stroll between the moral alleyways of life, though, it just might fill your heart.

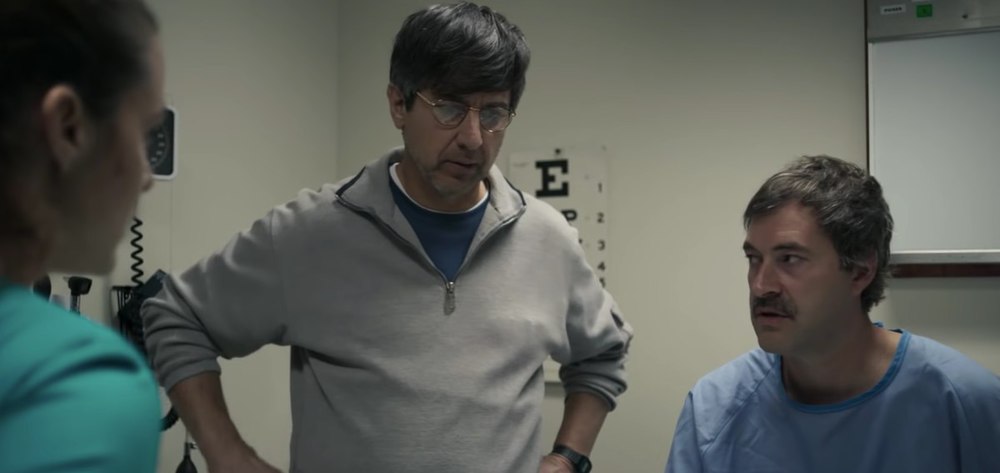

In The Four Loves, C.S. Lewis separates romantic love (Eros) from that of friendship (Philia) in spatial terms:

“lovers are normally face to face, absorbed in each other; friends, side by side, absorbed in some common interest.”

Yet as romance progresses, the former nearly always tilts toward the latter. Having found the peaks to be elusive and fleeting,

couples build a foundation on sturdier material: shared interests, shared goals, a consciously shared life. They move, together,

in some forward direction.

Sometimes, though, that momentum can blind them to the initial romance; the goal ceases to be for Us and becomes

for itself. That’s how Rachel (Kathryn Hahn) and Richard (Paul Giamatti) strike me when we enter their Private Life,

solemnly injecting and masturbating (respectively) in a fertility clinic. After umpteenth fruitless pregnancy attempts, they’ve

finally resolved to give IVF a shot—every possible shot, to be more specific.

They ask favors of family; they prowl diners for eggs; they spend countless hours in pursuit of one glorious hypothetical future.

Parenthood. Family. Us. So fervently do they push for their two to be three, they’ve rendered the former almost invisible.

But I never believe that it’s absent. I think it’s petrified, crystalized; a lattice of mutual frustration, of rueful laughter, communal

fatigue. They share some ineffable bond. It makes even the most wrenching shouting match play with a hint of a smirk; they

might look on the outside like they’re falling apart, but they’re both in on the same bad cosmic joke.

Maybe, one day, they’ll find that family they’ve been looking for. Or maybe their search only highlights the one they’ve already got.

In The Four Loves, C.S. Lewis separates romantic love (Eros) from that of friendship (Philia) in spatial terms:

“lovers are normally face to face, absorbed in each other; friends, side by side, absorbed in some common interest.”

Yet as romance progresses, the former nearly always tilts toward the latter. Having found the peaks to be elusive and fleeting,

couples build a foundation on sturdier material: shared interests, shared goals, a consciously shared life. They move, together,

in some forward direction.

Sometimes, though, that momentum can blind them to the initial romance; the goal ceases to be for Us and becomes

for itself. That’s how Rachel (Kathryn Hahn) and Richard (Paul Giamatti) strike me when we enter their Private Life,

solemnly injecting and masturbating (respectively) in a fertility clinic. After umpteenth fruitless pregnancy attempts, they’ve

finally resolved to give IVF a shot—every possible shot, to be more specific.

They ask favors of family; they prowl diners for eggs; they spend countless hours in pursuit of one glorious hypothetical future.

Parenthood. Family. Us. So fervently do they push for their two to be three, they’ve rendered the former almost invisible.

But I never believe that it’s absent. I think it’s petrified, crystalized; a lattice of mutual frustration, of rueful laughter, communal

fatigue. They share some ineffable bond. It makes even the most wrenching shouting match play with a hint of a smirk; they

might look on the outside like they’re falling apart, but they’re both in on the same bad cosmic joke.

Maybe, one day, they’ll find that family they’ve been looking for. Or maybe their search only highlights the one they’ve already got.

When confronted with the iciness of the world around us, it’s tempting to respond in kind: to feel guarded, cynical, above all this shit.

And sometimes it’s right to fight back; sometimes it’s necessary to close. But for many of us, that

anger becomes a vicious cycle, a joyless arms race toward mutually assured division.

What if we break the cycle? What if we could combat the world’s darkness with unlikely light?

Two films this year remind us that it’s possible to stare into the abyss and find childlike joy.

To find empathy in the tiniest struggle, and hope in the middle of a yawning ravine.

Fred Rogers has always been a beacon of light; if anything, that lightness was his signature brand.

But in the political moment Won’t You Be My Neighbor finds itself in, his joy represents something more, something borderline radical.

His delicate affect against Trump’s heavy bluster; his unwavering gaze against our dunks and our smirks.

The way his voice cracks when learning of the death of a pet; the way he addresses the camera like it’s the most interesting person in the world.

The way he patiently nods at our fears and our grief.

He challenges us to take this world seriously, to not only acknowledge its pain in the abstract

but to process it, feel it. To see political strife and say “let me try to understand this.”

To feel the weight of our sadness and ask “how can I be a balm?” With a documentary as direct and unshowy as Rogers himself,

Morgan Neville argues that kindness was neither tactic nor facade. It was a higher calling, a ministry.

And in years like this one, where the mad that we feel feels stark and overwhelming, his call is irresistible.

It’s a simple lesson, so obvious it becomes invisible: hear each other, love each other, meet the world with a smile.

Writing it feels hokey and evangelical. Witnessing it brought me to tears.

Fred Rogers has always been a beacon of light; if anything, that lightness was his signature brand.

But in the political moment Won’t You Be My Neighbor finds itself in, his joy represents something more, something borderline radical.

His delicate affect against Trump’s heavy bluster; his unwavering gaze against our dunks and our smirks.

The way his voice cracks when learning of the death of a pet; the way he addresses the camera like it’s the most interesting person in the world.

The way he patiently nods at our fears and our grief.

He challenges us to take this world seriously, to not only acknowledge its pain in the abstract

but to process it, feel it. To see political strife and say “let me try to understand this.”

To feel the weight of our sadness and ask “how can I be a balm?” With a documentary as direct and unshowy as Rogers himself,

Morgan Neville argues that kindness was neither tactic nor facade. It was a higher calling, a ministry.

And in years like this one, where the mad that we feel feels stark and overwhelming, his call is irresistible.

It’s a simple lesson, so obvious it becomes invisible: hear each other, love each other, meet the world with a smile.

Writing it feels hokey and evangelical. Witnessing it brought me to tears.

Nothing, though, got the tears flowing quite as much as Eighth Grade (full review).

In concept, Bo Burnham’s debut sounded like precisely the wrong approach to 2018: an older male director co-opting the experience of a 13-year-old girl.

In practice, it’s a modern day answer to Rogers’ challenge—and a bit of a miracle at that. It’s an exercise in looking Growing Up levelly in the eye

and saying “I hear you, I care about you, I take you seriously. Your problems are real, and they are precisely as heavy as you tell me they are.”

Kayla (Elsie Fisher) is a bighearted girl on the cusp of adolescence, straining the align the her she knows herself to be

with the her that keeps breaking out. She’s endlessly empathetic but with nowhere to put it, her brilliant inner-monologue turned

clumsy when spoken aloud. She has that good-humored personality that desperately nods along before it even gets the joke—a

brand of infectious okay-ness made no less endearing by the anxiety that fuels it. She wants what we all wanted

before learning it was impossible: to “be normal”, to “fit in”, to keep girl in the mirror from falling hopelessly short.

She hasn’t yet learned that we all feel that, always, or that falling short can be the most beautiful thing.

But as slowly and surely as we did, she will. And when Kayla finally reaches that self-acceptance,

that hope, we’re all a bit stronger for the trek.

Like Ladybird without the audibly-penned cleverness,

or Edge of Seventeen without a hint of an edge, or Boyhood without

Linklater’s (charming) indulgence. Eighth Grade is so achingly earnest, so effortlessly observed, so heartfelt and vulnerable and

perfectly concise, I almost want to downplay how much I love it. How dare I put a film about a preteen girl above Accepted High Art™?

But if Kayla can alchemize her awkwardness into “Gucci”, and Burnham can mine the most overdone genre for something poignant and new,

I think we all can leave room for a little of magic. 2018 gave us enough to feel dour about. For all the joy Kayla brought me,

I’m rounding her story up to perfect.

Nothing, though, got the tears flowing quite as much as Eighth Grade (full review).

In concept, Bo Burnham’s debut sounded like precisely the wrong approach to 2018: an older male director co-opting the experience of a 13-year-old girl.

In practice, it’s a modern day answer to Rogers’ challenge—and a bit of a miracle at that. It’s an exercise in looking Growing Up levelly in the eye

and saying “I hear you, I care about you, I take you seriously. Your problems are real, and they are precisely as heavy as you tell me they are.”

Kayla (Elsie Fisher) is a bighearted girl on the cusp of adolescence, straining the align the her she knows herself to be

with the her that keeps breaking out. She’s endlessly empathetic but with nowhere to put it, her brilliant inner-monologue turned

clumsy when spoken aloud. She has that good-humored personality that desperately nods along before it even gets the joke—a

brand of infectious okay-ness made no less endearing by the anxiety that fuels it. She wants what we all wanted

before learning it was impossible: to “be normal”, to “fit in”, to keep girl in the mirror from falling hopelessly short.

She hasn’t yet learned that we all feel that, always, or that falling short can be the most beautiful thing.

But as slowly and surely as we did, she will. And when Kayla finally reaches that self-acceptance,

that hope, we’re all a bit stronger for the trek.

Like Ladybird without the audibly-penned cleverness,

or Edge of Seventeen without a hint of an edge, or Boyhood without

Linklater’s (charming) indulgence. Eighth Grade is so achingly earnest, so effortlessly observed, so heartfelt and vulnerable and

perfectly concise, I almost want to downplay how much I love it. How dare I put a film about a preteen girl above Accepted High Art™?

But if Kayla can alchemize her awkwardness into “Gucci”, and Burnham can mine the most overdone genre for something poignant and new,

I think we all can leave room for a little of magic. 2018 gave us enough to feel dour about. For all the joy Kayla brought me,

I’m rounding her story up to perfect.

I can’t tell you how tempting it was to end on that note: to bask in the upswing and let joy have the final word.

And in other years, I might have—there’s immense value in optimism, in digging for goodness and light.

But if the year has taught me anything, it’s that optimism is a gift not all of us are afforded.

Too often, our desire for tidy resolution becomes an excuse to paper over others’ concern.

The truth is that none of these responses do the year justice: not joy, not anger, not redemption or clarity.

No, if anything defined 2018, it was in its utter refusal to resolve. These films boldly follow suit.

They acknowledge our contradictions—our joys and sorrows—with an honesty that defies all conclusion.

They resist all attempts self-definition; they refuse to be merely one thing.

If I could name one movie that perfectly captures the spirit of the year, it would be Carlos López Estrada’s Blindspotting.

Following a few days in the life of Collin (Daveed Diggs) as he struggles to make sense trauma while surviving his parole, it’s a film

that thrives on contradictory perspective. When we meet Collin he seems hopeful and upbeat,

till a witnessed act of police brutality sends his worldview spinning.

For the rest of the film he’s haunted by dual interpretations, by an uneasy alliance of darkness and light.

We feel both the relief of his freedom and the tightness of its bounds; see the beauty of his Oakland home

and the threat that looms over it. Every siren becomes an omen, every moment something borrowed at risk of being withdrawn.

Even the comic beats—of which there are surprisingly many—feel tenuous, foreboding; as if the whole of Collin’s existence is one

plot point away from collapse. That mish-mash of moods permeates the city as a whole: bubbly conveniences

which mask the pain of gentrification, a sense of identity that’s constantly in flux.

Collin feels them both changing, and not only for the worse—maybe he was holding on to too much anger, maybe the

green juice really is better for his health. But the means of that change—the system that forced it, the motive that belies

it—it’s toxic, unwelcome, unjust. So who should he be, and who should he be it for?

Blindspotting is an urgent examination of race in America, both universal and specific, a public airing of grievances and a personal reckoning.

It’s jarring and insistent; a film

whose spoken word pieces shook me with more ferocity than any thriller this year.

And its message is less a resolution than a desperate call to arms: “I am both pictures! See both pictures!”

If I could name one movie that perfectly captures the spirit of the year, it would be Carlos López Estrada’s Blindspotting.

Following a few days in the life of Collin (Daveed Diggs) as he struggles to make sense trauma while surviving his parole, it’s a film

that thrives on contradictory perspective. When we meet Collin he seems hopeful and upbeat,

till a witnessed act of police brutality sends his worldview spinning.

For the rest of the film he’s haunted by dual interpretations, by an uneasy alliance of darkness and light.

We feel both the relief of his freedom and the tightness of its bounds; see the beauty of his Oakland home