Cut to the chase: Just want to see the list of movies? No problem.

Previous write-ups: Check out the last eight end-of-year lists to get a sense of our similarities and differences.

Podcast: You can listen to my straightforward Top 10 list on The Spoiler Warning.

Introduction: Some Kind of Normal

I always like to start these by reflecting on the year, and in recent write-ups the pandemic has loomed large. 2020 was a tidal wave of collective emotion; 2021 was a kaleidoscope, a mass splintering. A unified global catastrophe crumbled into a thousand partial, personal threats—slipping on marbles, never quite confident in hope or cynicism.

2022 marked a “return to normal,” though as far as I can tell, our conditions haven’t changed. Last winter San Francisco was still 80% masked and treating “six feet apart” as a mandate; zero relevant breakthroughs later, the percentage is down to single digits. Having spent a year divided, it’s as if the world finally found one point of agreement—everyone was tired of swimming upstream. And so “normal” became a self-fulfilling prophecy, a sort of reverse prisoner’s dilemma. “There’s no point in trying if everyone else has given up,” we lamented in unison, satisfying our own condition.

As much as it gives me whiplash, I have no high horse to judge from. I feel the same paradoxical impulses, the same internal reversion to the mean. For an experiment which filled every groove of the human experience, the results are overwhelmingly consistent: Eventually, “normal” reasserts itself. Call it hypocritical, or selfish, or intentionally short-sighted (and I do, with some frequency depending on my mood). But empirically speaking, it’s human.

If “normal” was a tacit admission of defeat, it was also an opportunity. Whatever we were returning to, we were in it for the long haul, and with that perspective came a chance at redefinition. Long-lived conversations reemerged with new energy over what kind of society we ought to create. Topics which had once been relegated to academia are now uttered by late-night hosts, debated in book clubs, paid lip-service before elections (if then immediately discarded). Despite frustrating efforts to redirect that energy, I refuse to believe it will dissipate. We’ve all spent two years witnessing our own malleability. This won’t be the last time we break and reform.

The films of 2022 were infused with that malleable spirit. As I went through my annual preparation for this list—whittling down my favorites into 10 thematic pairs1—I was struck by just how many were intent on reinvention. Some took aim at the world around them: decrying complacency, jeering at hypocrisy, cheering on the crumbling of perverse, outdated structures. Others pointed inward, asking existential questions. What do we leave behind? What is the weight of human kindness? Every year a film or two will defy genre conventions, but this year’s favorites did so as a matter of habit, using every tool available to tear down or rebuild. If studios learn anything from 2022’s major success stories, that irreverence will be with us for a while.

As mentioned above, I won’t be ranking individual films2. There’s no shortage of wonderful critics who provide that service, and frankly, I find the exercise stressful—forcing me to focus on implied exclusions via an arbitrary number. What I love about this time of year is the chance it gives me to zoom out and find patterns, to explore why the things I loved spoke to me in the first place. For that, I’ve found pairing my favorites to be a more satisfying challenge; the scoring is still fuzzy, but more self-evidently so. (And hey, if your personal favorite didn’t make this list, just assume I’m not creative enough to have found a pairing for it! 3)

Counting down to my number one pairing of 2022:

Theatrical Bonus: Sacrificial Clowns – Top Gun: Maverick and Jackass Forever ↯

10) The Myth of a Middle Ground – Emergency and Athena ↯

9) Through a Keyhole – The Eternal Daughter and Saint Omer ↯

8) Don’t Look Away – All the Beauty and the Bloodshed and Holy Spider ↯

7) Immortalized in Light – Fire of Love and After Yang ↯

6) Turning the Tables – RRR and The Woman King ↯

5) Feeding the Void – The Menu and White Noise ↯

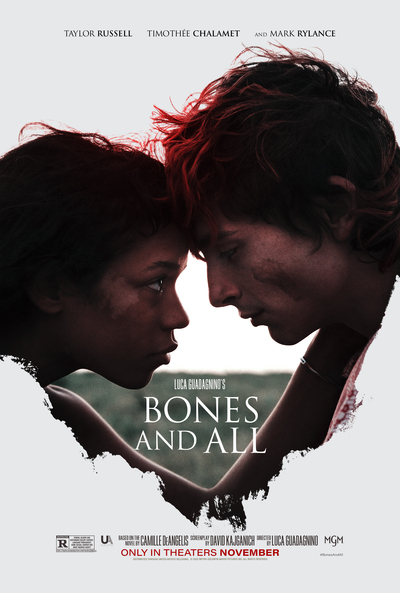

4) The Monster Inside – Bones and All and We’re All Going to the World’s Fair ↯

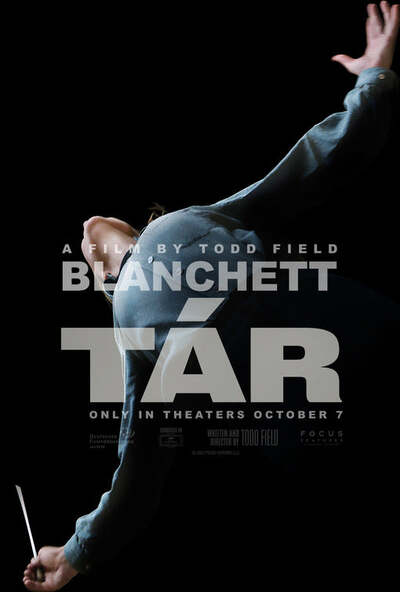

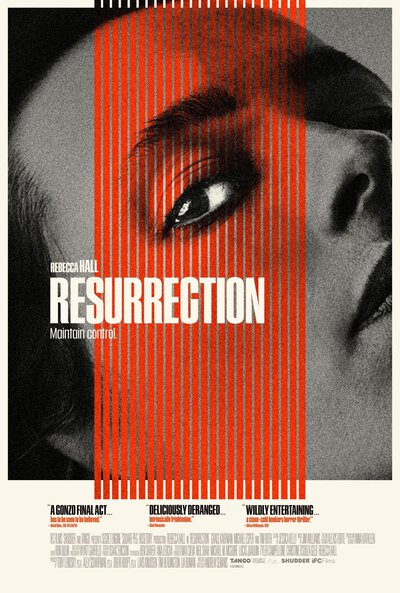

3) Confidence as Costume – TÁR and Resurrection ↯

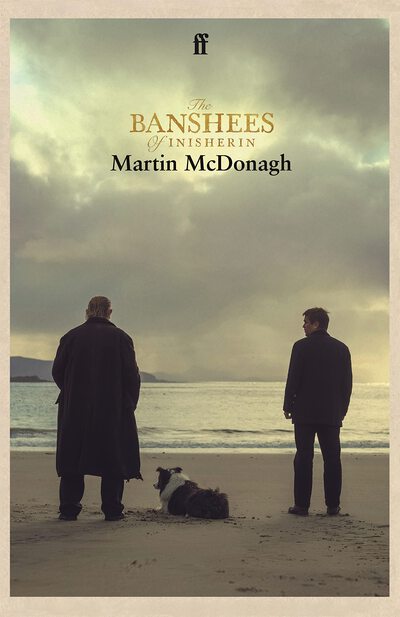

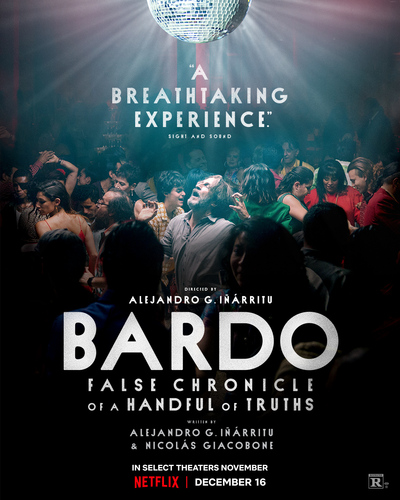

2) A Legacy for Whom? – The Banshees of Inisherin and BARDO, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths ↯

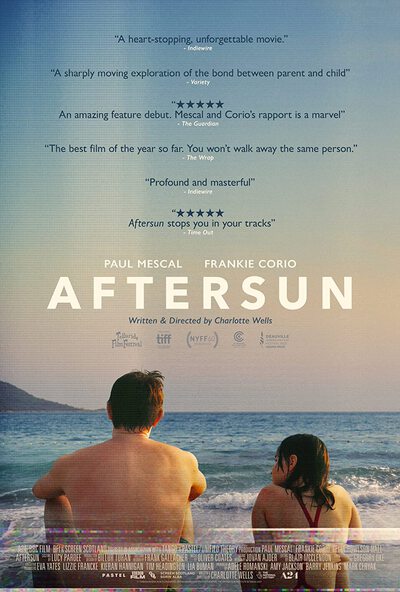

1) Clinging Through the Waves – Aftersun and Everything Everywhere All at Once ↯

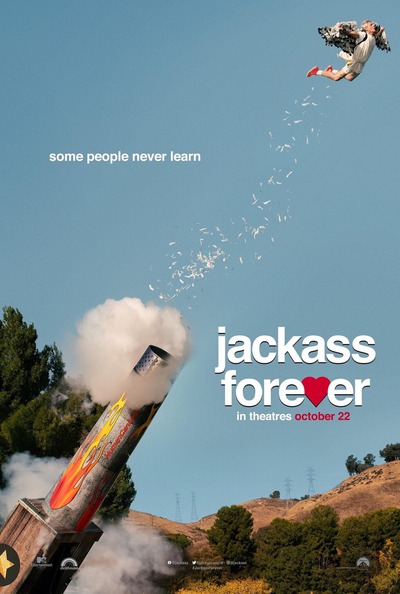

Theatrical Bonus: Sacrificial Clowns – Top Gun: Maverick and Jackass Forever

By late 2021 I was already dipping a toe back in theatres, but with caution came extreme selectivity. Theatres were a means to an end, an obstacle only to be endured for films I knew I wanted to see. The joy of the “experience” was never the point.

In 2022, that joy came roaring back to life. Armed with an N95 and a revised risk calculation, I opted for in-person screenings as a matter of habit. For the first time in two years, I saw the presence of an audience not as a threat, but a bonus.

This award is for the screenings which most exemplified that bonus: two big, silly, surprisingly endearing spectacles which used the energy of my neighbors as an essential ingredient. As if to prove just how powerful that ingredient was, both of these movies function as “legasequels,” trafficking in nostalgia for a thing I had no personal connection to. I absorbed the crowd’s nostalgia through osmosis.

What could I possibly say about Top Gun: Maverick that hasn’t been said a thousand times? I genuinely don’t know, and I don’t think it matters. If Maverick proves anything, it’s that novelty is overrated. Sometimes you just want the band to play the hits. Sometimes you want to forget about plot, character growth, and troubling geopolitical implications and just ride a roller coaster. Of course it’s running on a pre-ordained track; of course the loops won’t hurt you. But if you throw up your hands and surrender to physics, you’ll feel the adrenaline of actual danger. Tom Cruise pulling off a simulated mission will feel exactly as death-defying as the one with real stakes—it’s all the same forces with the same cheering crowd, it’s all just a matter of perspective. This is the sort of thrill ride you feel in your bones.

What could I possibly say about Top Gun: Maverick that hasn’t been said a thousand times? I genuinely don’t know, and I don’t think it matters. If Maverick proves anything, it’s that novelty is overrated. Sometimes you just want the band to play the hits. Sometimes you want to forget about plot, character growth, and troubling geopolitical implications and just ride a roller coaster. Of course it’s running on a pre-ordained track; of course the loops won’t hurt you. But if you throw up your hands and surrender to physics, you’ll feel the adrenaline of actual danger. Tom Cruise pulling off a simulated mission will feel exactly as death-defying as the one with real stakes—it’s all the same forces with the same cheering crowd, it’s all just a matter of perspective. This is the sort of thrill ride you feel in your bones.

Jackass Forever is another movie you feel in your bones, and the primary feeling is pain. There’s a reason my wife didn’t join me in this screening; it’s the same reason I never in a million years thought I’d be putting it on a list. I am nothing like these people. I have never cared about their show. It physically hurts me to watch them! So why did I love it? The best answer I can give is “catharsis.” As we strangers gathered together in the theatre, crying out “OOOOOH” and “NOOOOO”s with the blunt repetition of a pogo stick, all that pain started to feel needed, somehow. A sharp release after two years of dull ache. Hilarious in the way the best nonsense is hilarious: hilarious that we were laughing, hilarious that at 11am on a Saturday in the midst of a still-raging pandemic we’d crawled out of our caves and put on shoes and pants to watch middle-aged men bruise for our amusement. It doesn’t make a lick of sense. It’s also the closest I’ve felt to a stranger in years.

Jackass Forever is another movie you feel in your bones, and the primary feeling is pain. There’s a reason my wife didn’t join me in this screening; it’s the same reason I never in a million years thought I’d be putting it on a list. I am nothing like these people. I have never cared about their show. It physically hurts me to watch them! So why did I love it? The best answer I can give is “catharsis.” As we strangers gathered together in the theatre, crying out “OOOOOH” and “NOOOOO”s with the blunt repetition of a pogo stick, all that pain started to feel needed, somehow. A sharp release after two years of dull ache. Hilarious in the way the best nonsense is hilarious: hilarious that we were laughing, hilarious that at 11am on a Saturday in the midst of a still-raging pandemic we’d crawled out of our caves and put on shoes and pants to watch middle-aged men bruise for our amusement. It doesn’t make a lick of sense. It’s also the closest I’ve felt to a stranger in years.

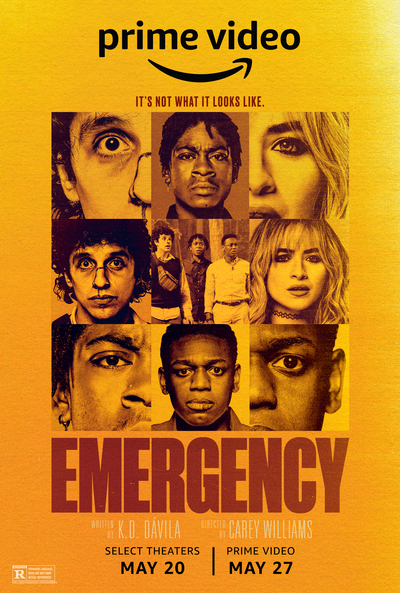

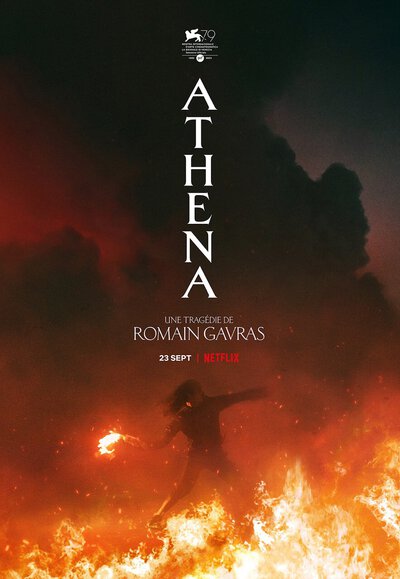

10. The Myth of the Middle Ground – Emergency and Athena

The year that promised a “return to normal” begged the question: What is an acceptable definition of the term? In practice, it felt like a euphemism for apathy, containment. Sand down the edges, bridge every possible divide, satisfy all in equal measure via some muted “middle ground.” Which is to say, satisfy no one.

Two films remind us that for the fault lines that really matter, there is often no such thing as a middle ground. That knee-jerk impulse to appease or cater, it doesn’t bring you any closer in some imagined game of inches. By choosing to internalize two irreconcilable points of view, you only dilute your own ability to fight.

In Emergency, Kunle is striving for respectability, unobtrusiveness. A Nigerian American with Ivy ambitions, he doesn’t rock the boat in his white-dominated university; he keeps his head down and plays by the rules. Whereas his best friend, Sean, is convinced the only move is not to play: Nothing he does will change society’s perception of him as a young Black man in this country. At the start of the film they’re a classic odd couple. Kunle wants to study but Sean wants to drink. Kunle avoids confrontations in class, Sean actively courts them to squeamish effect. But when they come home to find an underage white girl unconscious in their living room, their competing theories of the world are rendered consequential, concrete. If Kunle is right, the social contract demands they contact the police. If Sean is right, that impulse could prove impossibly naive—and dangerous. Are they protagonists in a hijinks-filled raunch-com, or the soon-to-be-victims of a harrowing drama? Eventually, someone needs to choose.

In Emergency, Kunle is striving for respectability, unobtrusiveness. A Nigerian American with Ivy ambitions, he doesn’t rock the boat in his white-dominated university; he keeps his head down and plays by the rules. Whereas his best friend, Sean, is convinced the only move is not to play: Nothing he does will change society’s perception of him as a young Black man in this country. At the start of the film they’re a classic odd couple. Kunle wants to study but Sean wants to drink. Kunle avoids confrontations in class, Sean actively courts them to squeamish effect. But when they come home to find an underage white girl unconscious in their living room, their competing theories of the world are rendered consequential, concrete. If Kunle is right, the social contract demands they contact the police. If Sean is right, that impulse could prove impossibly naive—and dangerous. Are they protagonists in a hijinks-filled raunch-com, or the soon-to-be-victims of a harrowing drama? Eventually, someone needs to choose.

The fault lines in Athena couldn’t be more apparent: There’s a physical barricade and two armed, opposing sides. A riot has broken out in the Parisian banlieue, following the murder of a 13-year-old Algerian boy at the (documented) hands of the police. On one side are the rioters, wielding bricks and Molotov cocktails, demanding that justice be served. On the other are the French police, decked head to toe in riot gear, insisting that order be maintained. In the film’s visual vocabulary, this is a war zone. Straddling both armies is Abdel, himself a resident of Athena, a literal soldier and the older brother of the deceased. He’s calling for peace and justice simultaneously. He wants to deescalate the tension, to translate each side to the other, to reason his way to an armistice. But there’s no way to diffuse a lit bomb while preserving its potency: You either neutralize its agency or you support its right to burst. Brimming with anger and raw kinetic energy, Athena is a sprint towards a reckoning.

The fault lines in Athena couldn’t be more apparent: There’s a physical barricade and two armed, opposing sides. A riot has broken out in the Parisian banlieue, following the murder of a 13-year-old Algerian boy at the (documented) hands of the police. On one side are the rioters, wielding bricks and Molotov cocktails, demanding that justice be served. On the other are the French police, decked head to toe in riot gear, insisting that order be maintained. In the film’s visual vocabulary, this is a war zone. Straddling both armies is Abdel, himself a resident of Athena, a literal soldier and the older brother of the deceased. He’s calling for peace and justice simultaneously. He wants to deescalate the tension, to translate each side to the other, to reason his way to an armistice. But there’s no way to diffuse a lit bomb while preserving its potency: You either neutralize its agency or you support its right to burst. Brimming with anger and raw kinetic energy, Athena is a sprint towards a reckoning.

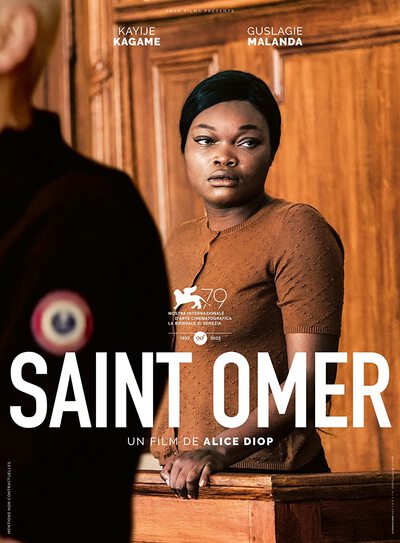

9. Through a Keyhole – The Eternal Daughter and Saint Omer

You can never really know another person. David Foster Wallace likened the challenge of human connection to trying to squeeze the contents of a room through a keyhole4—that gnawing asymmetry between inside and outside, between the infinite complexity we feel and the shallow language we have to express it.

These films explore how that asymmetry manifests for those on either side. The difficulty of peering in, the loneliness of being trapped, and the mysterious way that push and pull becomes a proxy for self understanding.

Julie wants to understand her mother, Rosalind. It’s at once an act of love and a creative pursuit: Having already mined her own life as inspiration for her films5, the director now feels an urge to widen the aperture. The Eternal Daughter, which follows the mother and daughter’s extended stay at an old, secluded hotel, functions as a claustrophobic two-hander between Tilda Swinton and…Tilda Swinton. Julie (Tilda) is trying to get Rosalind (Tilda) to open up, preferably in the vicinity of a tape recorder. She coaxes out childhood reminiscences over wine and dinner; she peppers her with questions during afternoon strolls. But the closer she tries to pull Rosalind in, the more the energy seems to shift. Nostalgic memories veer into mourning. A birthday celebration turns unexpectedly tense. Even the hotel grounds feel uncertain, askew, thrumming with secrets that deliberately evade her. Why is it so hard to see each other clearly—even when they have seemingly everything in common, they both desperately want it, and they’ve blocked out the entire world to do so?

Julie wants to understand her mother, Rosalind. It’s at once an act of love and a creative pursuit: Having already mined her own life as inspiration for her films5, the director now feels an urge to widen the aperture. The Eternal Daughter, which follows the mother and daughter’s extended stay at an old, secluded hotel, functions as a claustrophobic two-hander between Tilda Swinton and…Tilda Swinton. Julie (Tilda) is trying to get Rosalind (Tilda) to open up, preferably in the vicinity of a tape recorder. She coaxes out childhood reminiscences over wine and dinner; she peppers her with questions during afternoon strolls. But the closer she tries to pull Rosalind in, the more the energy seems to shift. Nostalgic memories veer into mourning. A birthday celebration turns unexpectedly tense. Even the hotel grounds feel uncertain, askew, thrumming with secrets that deliberately evade her. Why is it so hard to see each other clearly—even when they have seemingly everything in common, they both desperately want it, and they’ve blocked out the entire world to do so?

Rama doesn’t know Laurence Coly. If her testimony in Saint Omer is to be believed, few people have even noticed Coly since she immigrated from Senegal, let alone known her. But like Julie to her mother, Rama is driven by a creative impulse to try. Hers is less an attempt to connect than it is to solve a terrible puzzle. What would possess this thoughtful speaker, motivated student, and by all accounts loving mother to drown her infant daughter? Played with perfect restraint by Guslagie Malanda, Coly denies the charge of infanticide yet disputes few, if any, details. She walks through her life story patiently, methodically, not wholly devoid of emotion but miscalibrated somehow. It’s as if after years of feeling unseen, she’s forgotten how to reveal herself at all. Was it an act of desperation? Was she in any way coerced? Surely Rama—French-Senegalese herself, a novelist of tragedies, and four months pregnant at the time of this case—can find a “why” that reconciles the mother with her inconceivable actions. Without it, how can she quarantine the horror from her own life? How can any of us?

Rama doesn’t know Laurence Coly. If her testimony in Saint Omer is to be believed, few people have even noticed Coly since she immigrated from Senegal, let alone known her. But like Julie to her mother, Rama is driven by a creative impulse to try. Hers is less an attempt to connect than it is to solve a terrible puzzle. What would possess this thoughtful speaker, motivated student, and by all accounts loving mother to drown her infant daughter? Played with perfect restraint by Guslagie Malanda, Coly denies the charge of infanticide yet disputes few, if any, details. She walks through her life story patiently, methodically, not wholly devoid of emotion but miscalibrated somehow. It’s as if after years of feeling unseen, she’s forgotten how to reveal herself at all. Was it an act of desperation? Was she in any way coerced? Surely Rama—French-Senegalese herself, a novelist of tragedies, and four months pregnant at the time of this case—can find a “why” that reconciles the mother with her inconceivable actions. Without it, how can she quarantine the horror from her own life? How can any of us?

8. Don’t Look Away – All the Beauty and the Bloodshed and Holy Spider

In a world that lets us curate every conceivable input, there’s value in active discomfort. The best acts of protest intentionally trouble us, making us internalize a wrongness which would otherwise stay hidden.

These films are about people who refuse to sweep troubling truths under the rug. With stubborn perseverance, they insist on bearing witness until the world takes notice.

Nan Goldin, the subject of All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, has devoted her life to telling stories. Some of those stories are painful; some are provocative; some are glamorizing; some are a disquieting combination of all three. Her goal isn’t to moralize or synthesize, it’s simply to highlight. And for the first hour or so of the film, I have to say I was caught off guard by the approach. Here was a documentary ostensibly about modern day activism and the opioid epidemic, which was spending the bulk of its time depicting the New York club scene of the 70’s and 80’s—reminiscing about an era which seemed at best unrelated to the current crisis, at worst stylistically complicit. Like one of Goldin’s slideshows, the film contextualizes by way of overwhelming. It asks us to sit with the unease until, eventually, connections start to form: between addiction and feeling discarded, between one epidemic and another. What emerges is less a message than an argument by example: You cannot fight what you don’t understand, and you cannot protect by way of euphemism. The messy, unpleasant, often brutal realities of life are our most potent weapons against a power that thrives on contentment. Look at it, before you try to solve it. Look at it, and make it impossible for them to look away.

Nan Goldin, the subject of All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, has devoted her life to telling stories. Some of those stories are painful; some are provocative; some are glamorizing; some are a disquieting combination of all three. Her goal isn’t to moralize or synthesize, it’s simply to highlight. And for the first hour or so of the film, I have to say I was caught off guard by the approach. Here was a documentary ostensibly about modern day activism and the opioid epidemic, which was spending the bulk of its time depicting the New York club scene of the 70’s and 80’s—reminiscing about an era which seemed at best unrelated to the current crisis, at worst stylistically complicit. Like one of Goldin’s slideshows, the film contextualizes by way of overwhelming. It asks us to sit with the unease until, eventually, connections start to form: between addiction and feeling discarded, between one epidemic and another. What emerges is less a message than an argument by example: You cannot fight what you don’t understand, and you cannot protect by way of euphemism. The messy, unpleasant, often brutal realities of life are our most potent weapons against a power that thrives on contentment. Look at it, before you try to solve it. Look at it, and make it impossible for them to look away.

The fact that Holy Spider exists at all feels like an act of political protest. A Persian-language procedural which unfolds like a depraved Fincher saga, it puts moral rot on full display and dares us to blink. The most brazen examples come from Saeed, a serial killer who preys on sex workers in the holy city of Mashhad. We open on one of his soon-to-be victims, and we follow until she is no longer living. Nothing, and I mean nothing, is left to the imagination. Saeed’s horrific crimes are being investigated by Arezoo6, a journalist who has taken an interest in the case. As she works to identify the killer, she is confronted with more pervasive sort of evil: No one seems particularly interested in catching him. Oh they decry murder in the abstract, of course. Police, politicians, and religious officials have no shortage of platitudes to give on that point. But to investigate with passion would require caring about the victims, and there it seems Arezoo stands alone. Released at a time when the women of Iran are courageously demanding equality, Holy Spider resounds with present-tense conviction. As with the powers Nan Goldin lobbied, lip service is cheap. Your character is revealed by those you actively protect, those you actively choose to see.

The fact that Holy Spider exists at all feels like an act of political protest. A Persian-language procedural which unfolds like a depraved Fincher saga, it puts moral rot on full display and dares us to blink. The most brazen examples come from Saeed, a serial killer who preys on sex workers in the holy city of Mashhad. We open on one of his soon-to-be victims, and we follow until she is no longer living. Nothing, and I mean nothing, is left to the imagination. Saeed’s horrific crimes are being investigated by Arezoo6, a journalist who has taken an interest in the case. As she works to identify the killer, she is confronted with more pervasive sort of evil: No one seems particularly interested in catching him. Oh they decry murder in the abstract, of course. Police, politicians, and religious officials have no shortage of platitudes to give on that point. But to investigate with passion would require caring about the victims, and there it seems Arezoo stands alone. Released at a time when the women of Iran are courageously demanding equality, Holy Spider resounds with present-tense conviction. As with the powers Nan Goldin lobbied, lip service is cheap. Your character is revealed by those you actively protect, those you actively choose to see.

7. Immortalized in Light – Fire of Love and After Yang

“Actively” is the operative word above. Multiple entries on this list touch on the idea of attention as currency. Choosing to direct it towards unpleasant truths. Resisting the impulse to spread it translucent. Focus as a catalyst for action.

These two films are about the value of focus on its own terms. They argue that our curiosity, our passion, the specific way we and only we see the world is a vital artifact.

Katia and Maurice Krafft love volcanoes. And I can think of no greater compliment than to say that watching Fire of Love made me love them too. Though the documentary includes multiple interviews with the volcanologist couple, its power doesn’t lie in their—or any—words. Rather, it lies in what they saw and preserved. Namely: gorgeous, terrifying, mesmeric footage of volcanoes in the act of erupting. Tiny silhouettes in heat-resistant silver, dwarfed against a skyscraper of magma. Smoke billowing like the fury of some vengeful Greek god. A color palette which has always existed—which is intricately tied with the creation of our world—yet somehow feels futuristic, alien whenever it’s on screen. It’s breathtaking, and at least to this viewer, an entirely novel sensation. By relentlessly pursuing their unorthodox obsessions, the Kraffts accomplished what so many artists aim to do. They made us see the world through their eyes, and see it as glorious.

Katia and Maurice Krafft love volcanoes. And I can think of no greater compliment than to say that watching Fire of Love made me love them too. Though the documentary includes multiple interviews with the volcanologist couple, its power doesn’t lie in their—or any—words. Rather, it lies in what they saw and preserved. Namely: gorgeous, terrifying, mesmeric footage of volcanoes in the act of erupting. Tiny silhouettes in heat-resistant silver, dwarfed against a skyscraper of magma. Smoke billowing like the fury of some vengeful Greek god. A color palette which has always existed—which is intricately tied with the creation of our world—yet somehow feels futuristic, alien whenever it’s on screen. It’s breathtaking, and at least to this viewer, an entirely novel sensation. By relentlessly pursuing their unorthodox obsessions, the Kraffts accomplished what so many artists aim to do. They made us see the world through their eyes, and see it as glorious.

In After Yang, the process is even more direct: We literally see the world through Yang’s eyes. When the titular robot becomes unresponsive, his (human) family is left in a state of muted grief. They can talk about solutions (to fix or to replace?) but their sorrow seems to linger on the tip of their tongue. By and large, the film follows their emotional lead: delicate, tentative, lush but only to a point, hovering just on the periphery of heartbreak. All of that changes when, for reasons I won’t spoil, we’re granted access to Yang’s memories. Or rather to his attention—a few seconds per day which Yang deemed worthy of preserving. As we cycle through disconnected fragments of memory, every previously-muted emotion hits with full force. It’s a moving experience, and its meaning has continued to gnaw at me after multiple viewings. Beyond language and rationalization, the most profound mark we leave behind might be the world as we remix it, the particular parts we choose to edit down. Whether a bubbling pool of magma or the perfect cup of tea, we construct the found art of our lives. We forage for beauty and compare notes.

In After Yang, the process is even more direct: We literally see the world through Yang’s eyes. When the titular robot becomes unresponsive, his (human) family is left in a state of muted grief. They can talk about solutions (to fix or to replace?) but their sorrow seems to linger on the tip of their tongue. By and large, the film follows their emotional lead: delicate, tentative, lush but only to a point, hovering just on the periphery of heartbreak. All of that changes when, for reasons I won’t spoil, we’re granted access to Yang’s memories. Or rather to his attention—a few seconds per day which Yang deemed worthy of preserving. As we cycle through disconnected fragments of memory, every previously-muted emotion hits with full force. It’s a moving experience, and its meaning has continued to gnaw at me after multiple viewings. Beyond language and rationalization, the most profound mark we leave behind might be the world as we remix it, the particular parts we choose to edit down. Whether a bubbling pool of magma or the perfect cup of tea, we construct the found art of our lives. We forage for beauty and compare notes.

6. Turning the Tables – RRR and The Woman King

As we continue to compare notes, one conclusion is inescapable: None of this is remotely fair, or right. Despite frustrating reversions in the name of #10’s “middle,” there is still a growing sense that the fundamentals of our society need to change: who makes the decisions, and who benefits.

There’s a time to forage and a time to hunt. These films are about heroes who see the world they live in and dare to imagine something better, forcibly flipping the script.

In my Theatrical Bonus, I highlighted two theatrical experiences in which the energy of the audience played a crucial ingredient. But I neglected to mention my single favorite example: a sold out, Tuesday night screening of RRR. Everything you’ve heard about the Tollywood epic is accurate and hyperbole-free. It’s riveting, propulsive, silly and enormous, bursting at the seams with so much inventive spectacle it makes the best MCU movies look like…well, like the other 26 MCU movies. I won’t try to thoughtfully articulate the plot, because A) I lack the context7 and B) it’s not the point. But this is an action film named (among other things) “Rise Roar Revolt”, and for all its over-the-top aspects, I felt a real jolt of revolutionary energy. Blockbusters tend to either explicitly root for, or limply apologize for, conventional power structures. It’s refreshing to leave one viscerally wanting to burn them to the ground.

In my Theatrical Bonus, I highlighted two theatrical experiences in which the energy of the audience played a crucial ingredient. But I neglected to mention my single favorite example: a sold out, Tuesday night screening of RRR. Everything you’ve heard about the Tollywood epic is accurate and hyperbole-free. It’s riveting, propulsive, silly and enormous, bursting at the seams with so much inventive spectacle it makes the best MCU movies look like…well, like the other 26 MCU movies. I won’t try to thoughtfully articulate the plot, because A) I lack the context7 and B) it’s not the point. But this is an action film named (among other things) “Rise Roar Revolt”, and for all its over-the-top aspects, I felt a real jolt of revolutionary energy. Blockbusters tend to either explicitly root for, or limply apologize for, conventional power structures. It’s refreshing to leave one viscerally wanting to burn them to the ground.

If RRR is a comic book retelling of known revolutionary history, The Woman King is a reimagining of the revolutions that could have been. It’s also an act of historical revelation. The film centers around the Agojie, an all-woman warrior unit who served the 19th century Kingdom of Dahomey in what is now (primarily) Benin. If this is your first time learning that an entirely woman-led fighting force not only existed, but existed for centuries, you aren’t alone: Beyond the bloody action sequences, the film’s most thrilling aspect might be that sense of discovery, excavation. Having established their well-recorded prowess in battle, the film turns its attention to possible points of inflection. What if the Agojie had been allowed to lead, rather than merely serve the King? What if the Kingdom wielded the brunt of its power against the encroaching Portuguese, against the slave trade itself? There are real stories, here, stochastic acts of revolution and revolt that are accumulated into one potent charge. Some view that as revisionistic; I view it as a battle cry. This is what the world could be. It only takes a spark.

If RRR is a comic book retelling of known revolutionary history, The Woman King is a reimagining of the revolutions that could have been. It’s also an act of historical revelation. The film centers around the Agojie, an all-woman warrior unit who served the 19th century Kingdom of Dahomey in what is now (primarily) Benin. If this is your first time learning that an entirely woman-led fighting force not only existed, but existed for centuries, you aren’t alone: Beyond the bloody action sequences, the film’s most thrilling aspect might be that sense of discovery, excavation. Having established their well-recorded prowess in battle, the film turns its attention to possible points of inflection. What if the Agojie had been allowed to lead, rather than merely serve the King? What if the Kingdom wielded the brunt of its power against the encroaching Portuguese, against the slave trade itself? There are real stories, here, stochastic acts of revolution and revolt that are accumulated into one potent charge. Some view that as revisionistic; I view it as a battle cry. This is what the world could be. It only takes a spark.

5. Feeding the Void – The Menu and White Noise

If change is thrilling, it’s also destabilizing. There’s a narcotizing calm that comes with being carried by the status quo. When the foundation disappears, we reach for others to replace it: an audience to perform to, a consensus to nestle within.

These films are about the emptiness inherent to those substitute foundations. Scathing and empathetic in equal measure, they both mock and indulge our inconsistencies.

Given the title, you might assume the comfort The Menu is skewering is food. And it is, in a sense—a horror film set at a world-renowned restaurant whose progressive tasting menu grows more violent by the course, it has plenty to say about elitism and dining. But the deepest targets of its ire have nothing to do with eating and everything to do with performance. It’s the Instagram story of the perfectly plated meal, the hallowed Authentic Experience™ fetishized to a commodity. Paying a premium for the bragging right of eating food you likely hate; exclusive membership to a club, password “mouthfeel.” It’s about the way wealth and the pursuit of status hollow you out, strip everything of enjoyment including the act of enjoying something. Like the best satirical comedies, The Menu knows how to execute on precisely what it’s criticizing. It knows how to be highbrow, how to sprinkle in a grace note or witheringly specific dig8, how to be precisely the sort of film this snooty armchair critic would adore. But it also knows how to please a crowd; when to sacrifice the technically perfect choice for the more immediately satisfying moment. A ten course tasting menu that isn’t afraid to be cheeseburger, it’s less an argument against indulgence than it is against self-defeating posturing. Whatever vapid thing you gorge yourself on, it had better at least be filling.

Given the title, you might assume the comfort The Menu is skewering is food. And it is, in a sense—a horror film set at a world-renowned restaurant whose progressive tasting menu grows more violent by the course, it has plenty to say about elitism and dining. But the deepest targets of its ire have nothing to do with eating and everything to do with performance. It’s the Instagram story of the perfectly plated meal, the hallowed Authentic Experience™ fetishized to a commodity. Paying a premium for the bragging right of eating food you likely hate; exclusive membership to a club, password “mouthfeel.” It’s about the way wealth and the pursuit of status hollow you out, strip everything of enjoyment including the act of enjoying something. Like the best satirical comedies, The Menu knows how to execute on precisely what it’s criticizing. It knows how to be highbrow, how to sprinkle in a grace note or witheringly specific dig8, how to be precisely the sort of film this snooty armchair critic would adore. But it also knows how to please a crowd; when to sacrifice the technically perfect choice for the more immediately satisfying moment. A ten course tasting menu that isn’t afraid to be cheeseburger, it’s less an argument against indulgence than it is against self-defeating posturing. Whatever vapid thing you gorge yourself on, it had better at least be filling.

White Noise is based on a major work of postmodern literature; there’s a chance it was assigned to you in college. Yet, perhaps more than any entry on this list, it reads like a critique of our particular decade. Culture has become fragmented and hyper-specific. A rising interest in the study of Hitler is paired with renewed enthusiasm for Elvis Presley. A massive Airborne Toxic Event causes widespread panic, exposing a subset of the population to a deadly toxin which, rather than act immediately and dramatically, has a statistical, long term impact on morbidity. Certainties are hard to tease out, and misinformation (“She’s having outdated symptoms!”) fills the vacuum. What does the population do when faced with their mortality? They play act, retreat to some semblance of normal. Same bleach white grocery stores proffering comforting brands, same navel-gazing lectures met with roaring applause. The world has split open but their lives remain the same—and if that facade is depressing, it’s also uniquely, laughably human. In the postmodern tradition, White Noise plays like a joyous contradiction. Like The Menu, it knows when to finger wag and when to appease, when to cut the intellectualizing and dance.

White Noise is based on a major work of postmodern literature; there’s a chance it was assigned to you in college. Yet, perhaps more than any entry on this list, it reads like a critique of our particular decade. Culture has become fragmented and hyper-specific. A rising interest in the study of Hitler is paired with renewed enthusiasm for Elvis Presley. A massive Airborne Toxic Event causes widespread panic, exposing a subset of the population to a deadly toxin which, rather than act immediately and dramatically, has a statistical, long term impact on morbidity. Certainties are hard to tease out, and misinformation (“She’s having outdated symptoms!”) fills the vacuum. What does the population do when faced with their mortality? They play act, retreat to some semblance of normal. Same bleach white grocery stores proffering comforting brands, same navel-gazing lectures met with roaring applause. The world has split open but their lives remain the same—and if that facade is depressing, it’s also uniquely, laughably human. In the postmodern tradition, White Noise plays like a joyous contradiction. Like The Menu, it knows when to finger wag and when to appease, when to cut the intellectualizing and dance.

4. The Monster Inside – Bones and All and We’re All Going to the World’s Fair

Despite every genuine attempt and higher-order certainty, we remain imperfect people with imperfect desires. So much of growing up is about coming to terms with that imperfection—shaping it, accepting it, fashioning keyhole-sized labels. It’s a lonely, often terrifying process.

These stories explore that loneliness, that fear. They’re about the negotiations inherent in coming to terms with yourself, struggling to stay hidden while desperate to be seen.

It’s tempting to read Bones and All purely as an allegory. Certainly, it has the raw materials. The queer-coded coming-of-age drama follows young cannibals living in Reagan-era America, whose desires thrust them to the fringes of society. Marked as definitionally “dangerous,” they’re left with no choice but to forge new ways of being. All the beauty, all the bloodshed. What I adore about this film, though, is its refusal to map neatly onto one didactic point. Drown out the social context and consider Maren and Lee on their own terms. They have this passion, this intensity of want they can’t control. It doesn’t just seem dangerous because it violates the social order; it is (in defiance of metaphor) a genuinely violent compulsion, a need to draw blood. They’ve hurt people in the past, and they’re likely to hurt again. Rather than ask us to fully fear them or forgive them, the film simply asks us to feel them. The dull ache of desire and the threat of its fulfillment. The self-loathing that comes after; if only you were stronger. How painful it must be to be at war with yourself. How freeing to lie back in the passenger seat, to peel off the armor, to share in the whole bloody mess. The text of the film is part horror, part tragedy, but the texture is pure romance. It’s love and sex and yearning and danger and self-hatred and -actualization, melded into one intractable feeling. It says “Take me, all of me, exactly as I am.”

It’s tempting to read Bones and All purely as an allegory. Certainly, it has the raw materials. The queer-coded coming-of-age drama follows young cannibals living in Reagan-era America, whose desires thrust them to the fringes of society. Marked as definitionally “dangerous,” they’re left with no choice but to forge new ways of being. All the beauty, all the bloodshed. What I adore about this film, though, is its refusal to map neatly onto one didactic point. Drown out the social context and consider Maren and Lee on their own terms. They have this passion, this intensity of want they can’t control. It doesn’t just seem dangerous because it violates the social order; it is (in defiance of metaphor) a genuinely violent compulsion, a need to draw blood. They’ve hurt people in the past, and they’re likely to hurt again. Rather than ask us to fully fear them or forgive them, the film simply asks us to feel them. The dull ache of desire and the threat of its fulfillment. The self-loathing that comes after; if only you were stronger. How painful it must be to be at war with yourself. How freeing to lie back in the passenger seat, to peel off the armor, to share in the whole bloody mess. The text of the film is part horror, part tragedy, but the texture is pure romance. It’s love and sex and yearning and danger and self-hatred and -actualization, melded into one intractable feeling. It says “Take me, all of me, exactly as I am.”

If Maren and Lee find belonging in the open road, Casey is searching for it in an endless, scrolling feed. By the time we meet the protagonist of We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, she’s already formed a truce with her demons. She knows that she’s hurting and she doesn’t expect it to stop. What she wants is to make it be important. To find some audience to connect her pain to something bigger, who can rescue her from the oppressiveness of her isolated teenage life. What they witness is unsettling; I won’t spoil it here. But beyond this film’s horror trappings lies what might be the most perceptive look at modern adolescence since Eighth Grade. Like Kayla and her YouTube channel—like the John Darnielle characters who hunt for meaning in mail-in RPGs and cryptic video returns—Casey is sending out a flare. I exist, and I am terrifying. Scrutinize my wrongnesses in Guadagnino close-up; scrub through every frame, uncover every clue. Notice me and all my gnarled edges.

If Maren and Lee find belonging in the open road, Casey is searching for it in an endless, scrolling feed. By the time we meet the protagonist of We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, she’s already formed a truce with her demons. She knows that she’s hurting and she doesn’t expect it to stop. What she wants is to make it be important. To find some audience to connect her pain to something bigger, who can rescue her from the oppressiveness of her isolated teenage life. What they witness is unsettling; I won’t spoil it here. But beyond this film’s horror trappings lies what might be the most perceptive look at modern adolescence since Eighth Grade. Like Kayla and her YouTube channel—like the John Darnielle characters who hunt for meaning in mail-in RPGs and cryptic video returns—Casey is sending out a flare. I exist, and I am terrifying. Scrutinize my wrongnesses in Guadagnino close-up; scrub through every frame, uncover every clue. Notice me and all my gnarled edges.

3. Confidence as Costume – TÁR and Resurrection

We forge an identity out of the raw materials we’re given, weave them into one consistent narrative. Soften things, curate for the keyhole. One danger of an echo chamber, then, is the flattening of self: the way it iteratively reflects our simplified narrative until it replaces the genuine artifact.

Our cultivated personalities can’t bear the weight of a disaster. These films depict a house of cards collapsing.

Lydia Tár is nobody’s victim. An accomplished conductor, composer, author, and public intellectual, she seems wholly in control of every facet of her life. After all, she fashioned it herself. TÁR is likewise a meticulous construction. In terms of pure craft, I consider it the most flawless entry on my list. The same, however, cannot be said for its namesake. In one early impromptu lecture, we’re given a glimpse of her contradictions. She’s engaging, dynamic, passionate, persuasive, and also patently, toxically wrong. Her arrogance is unwavering and all-consuming. It will take no small force to uproot it. But piece by piece, with virtuosic precision, the film guides us through the movements that will do so. It first asks us to see the world from her eyes, to be hypnotized by her self mythology. Thus calibrated, we—like Lydia—are primed to perceive whatever threatens her position as a mysterious (even supernatural) threat. What else can kill a god, can take down nobody’s victim? The result is slowly unfurling nightmare.

Lydia Tár is nobody’s victim. An accomplished conductor, composer, author, and public intellectual, she seems wholly in control of every facet of her life. After all, she fashioned it herself. TÁR is likewise a meticulous construction. In terms of pure craft, I consider it the most flawless entry on my list. The same, however, cannot be said for its namesake. In one early impromptu lecture, we’re given a glimpse of her contradictions. She’s engaging, dynamic, passionate, persuasive, and also patently, toxically wrong. Her arrogance is unwavering and all-consuming. It will take no small force to uproot it. But piece by piece, with virtuosic precision, the film guides us through the movements that will do so. It first asks us to see the world from her eyes, to be hypnotized by her self mythology. Thus calibrated, we—like Lydia—are primed to perceive whatever threatens her position as a mysterious (even supernatural) threat. What else can kill a god, can take down nobody’s victim? The result is slowly unfurling nightmare.

The nightmare in Resurrection is decidedly more literal. Margaret’s tormentor is no hazy manifestation of some inevitable future reckoning. He’s a flesh-and-blood man sitting on a park bench in broad daylight, sharpened canines puncturing a cruel and feral smile. Outwardly, Margaret exists as the epitome of confidence: the high-powered executive who plays her boardroom like a fiddle; the single mother who champions self-sufficiency to a fault. But now he’s clawed his way back from the past to the park bench, and brought with him a host of anxieties. If this sounds like the plot of a demented horror flick—and, spoilers, it absolutely is—it’s also a riveting drama. Over the course of a monologue of Bergman proportions, we watch Margaret peel back every carefully-constructed layer. Her unraveling is too massive to be pigeonholed by genre: She, and the film, defy everything. It’s unnerving to witness someone tear so much away. I have no clue what to make of it; it still lives inside me.

The nightmare in Resurrection is decidedly more literal. Margaret’s tormentor is no hazy manifestation of some inevitable future reckoning. He’s a flesh-and-blood man sitting on a park bench in broad daylight, sharpened canines puncturing a cruel and feral smile. Outwardly, Margaret exists as the epitome of confidence: the high-powered executive who plays her boardroom like a fiddle; the single mother who champions self-sufficiency to a fault. But now he’s clawed his way back from the past to the park bench, and brought with him a host of anxieties. If this sounds like the plot of a demented horror flick—and, spoilers, it absolutely is—it’s also a riveting drama. Over the course of a monologue of Bergman proportions, we watch Margaret peel back every carefully-constructed layer. Her unraveling is too massive to be pigeonholed by genre: She, and the film, defy everything. It’s unnerving to witness someone tear so much away. I have no clue what to make of it; it still lives inside me.

2. A Legacy for Whom? – The Banshees of Inisherin and BARDO, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths

Multiple entries on this list explore what we leave behind. Some luxuriate in it, others spiral into existential crises over it. But a question remains: For whom do we tailor it? Who is it that ultimately matters?

These are stories about art, legacy, and inevitable trade-offs. Confronted with their own mortality, their middle-aged protagonists know they want to leave a mark. They just can’t seem to settle on an audience.

Everyone on Inisherin seems to have a different answer. Pádraic is at peace with the smallness of his life and sees contentment as the ultimate aim. The people he loves are his legacy. His sister Siobhán wants to expand her horizons: She hasn’t seen enough of the world to know whom to live for. Then there’s Colm, whose existential crisis serves as The Banshees of Inisherin’s narrative fulcrum. Colm is fine with smallness, with a narrow field of influence. He has no desire to leave the confines of his home. What he can’t stand is that which Pádraic most values: impermanence. Evening pints with buddies, hours in the company of animals, unsung opportunities for kindness. They’re special precisely because they’re intimate, fleeting. But music—music is eternal. Dwarfed by the infinite, Colm’s day-to-day relationships seem like petty distractions. He doesn’t want to be cruel, exactly, but what is the weight of kindness when stacked up against eternal pursuits? If all the kindness of a lifetime were hurled against a door, would it make a sound worth studying like Mozart? A pitch black comedy about the human condition, Banshees refuses to offer up a villain or an answer.

Everyone on Inisherin seems to have a different answer. Pádraic is at peace with the smallness of his life and sees contentment as the ultimate aim. The people he loves are his legacy. His sister Siobhán wants to expand her horizons: She hasn’t seen enough of the world to know whom to live for. Then there’s Colm, whose existential crisis serves as The Banshees of Inisherin’s narrative fulcrum. Colm is fine with smallness, with a narrow field of influence. He has no desire to leave the confines of his home. What he can’t stand is that which Pádraic most values: impermanence. Evening pints with buddies, hours in the company of animals, unsung opportunities for kindness. They’re special precisely because they’re intimate, fleeting. But music—music is eternal. Dwarfed by the infinite, Colm’s day-to-day relationships seem like petty distractions. He doesn’t want to be cruel, exactly, but what is the weight of kindness when stacked up against eternal pursuits? If all the kindness of a lifetime were hurled against a door, would it make a sound worth studying like Mozart? A pitch black comedy about the human condition, Banshees refuses to offer up a villain or an answer.

In BARDO, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths, the argument isn’t divvied up between a roving cast of townspeople: Silverio embodies every side at once. The immediacy of family, the permanence of art, the security of a hometown, the tug of new horizons. To further his directorial ambitions, the thinly-veiled Iñáritu surrogate left Mexico City for Los Angeles early in his career. And on paper, the gambit paid off: He is critically acclaimed, his films are widely seen, and his family still lives under one roof. But now, as he prepares a speech for a ceremony held in his honor, he questions every decision. He moved to California to make his art more accessible, but by leaving the city that forged him, has he diluted his own perspective? Is it onanistic to strive for purity, or is it “selling out” to cater to your audience? And who is this audience anyway—pretentious snobs on one extreme, blood-hungry mob on the other. He still knows how to dazzle them, but to what end? Iñáritu still knows how to dazzle us too. Framing Silverio’s inner turmoil as a series of Fellini-esque flights of fancy, his self-critique is nothing if not wildly entertaining. Critics have called it indulgent, but I was bowled over by BARDO’s towering self-awareness9. If only doubt were always this majestic.

In BARDO, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths, the argument isn’t divvied up between a roving cast of townspeople: Silverio embodies every side at once. The immediacy of family, the permanence of art, the security of a hometown, the tug of new horizons. To further his directorial ambitions, the thinly-veiled Iñáritu surrogate left Mexico City for Los Angeles early in his career. And on paper, the gambit paid off: He is critically acclaimed, his films are widely seen, and his family still lives under one roof. But now, as he prepares a speech for a ceremony held in his honor, he questions every decision. He moved to California to make his art more accessible, but by leaving the city that forged him, has he diluted his own perspective? Is it onanistic to strive for purity, or is it “selling out” to cater to your audience? And who is this audience anyway—pretentious snobs on one extreme, blood-hungry mob on the other. He still knows how to dazzle them, but to what end? Iñáritu still knows how to dazzle us too. Framing Silverio’s inner turmoil as a series of Fellini-esque flights of fancy, his self-critique is nothing if not wildly entertaining. Critics have called it indulgent, but I was bowled over by BARDO’s towering self-awareness9. If only doubt were always this majestic.

1. Clinging Through the Waves: Aftersun and Everything Everywhere All at Once

Which leads me to the final theme, of this and so many of my lists. It’s the obvious truth that somehow never fails to surprise me, what Colm has rationalized himself out of and Lee and Maren are searching for. The importance of human connection. We cling to each other through uncertain times as a balm against the emptiness that threatens to hollow us, the white noise that drowns out all meaning.

These films are about a desperate sort of clutch. One hurting person saying to another “I don’t know what to do any more than you do. But in this moment, let me tether you.” Solace, not through certain answers, but a willingness to reiterate simple questions. Why can’t we just be kind? Why can’t we give love one more chance?

Immediately after leaving my screening of Aftersun, I knew it would land in my number one slot10. If you’ve seen it, I’m sure you can conjure the exact sequence I’m alluding to with the title of this pairing. It’s the emotional climax, the musical moment of the year, the coda to a dance we’ve spent the entire runtime watching. Participants may rotate, but the motion remains the same: Sophie to Calum, Calum to Sophie, camera to subject, present to past. One reaches, the other falls. We’re given hints of a story beyond their vacation, and so much emphasis is placed on deciphering it (our review included). But that fundamental feeling of grasping, of pulling—remove every bit of context and it lingers just the same. It permeates their smallest interactions: hidden looks, wordless gestures, half smiles flickering like a neon OPEN. It also permeates those moments when no one is in frame; paragliders overhead, waves lapping and receding. To find a film which carries such a consistent emotional current—it’s such a rare and wonderful treasure. Aftersun refuses to let me go.

Immediately after leaving my screening of Aftersun, I knew it would land in my number one slot10. If you’ve seen it, I’m sure you can conjure the exact sequence I’m alluding to with the title of this pairing. It’s the emotional climax, the musical moment of the year, the coda to a dance we’ve spent the entire runtime watching. Participants may rotate, but the motion remains the same: Sophie to Calum, Calum to Sophie, camera to subject, present to past. One reaches, the other falls. We’re given hints of a story beyond their vacation, and so much emphasis is placed on deciphering it (our review included). But that fundamental feeling of grasping, of pulling—remove every bit of context and it lingers just the same. It permeates their smallest interactions: hidden looks, wordless gestures, half smiles flickering like a neon OPEN. It also permeates those moments when no one is in frame; paragliders overhead, waves lapping and receding. To find a film which carries such a consistent emotional current—it’s such a rare and wonderful treasure. Aftersun refuses to let me go.

If Aftersun is my personal favorite of the year, Everything Everywhere All at Once is the film which best encapsulates the year. Watching this frenetic multiverse saga feels like living through 2022: overwhelming, oversaturated, tugged in too many directions to move. Evelyn feels it; so does Joy. That temptation to be rendered numb by the enormity of everything, to be swept up in the riptide of Casey’s endless scroll—it is so, so strong. Which is why we’re lucky to find people who grab on, who pull, who insist upon meaning despite a wave of convincing arguments to the contrary. What I love about Everything Everywhere is that it has no desire to make sense. It knows that to limit ourselves to rationality is to lay down our greatest weapon in the fight: our uncanny ability to hope against reason. Particularly when we’re hoping on someone else’s behalf. What we lack in the first person we give doubly in the second, life rafts anchoring life rafts, conjuring solid ground from scratch.

If Aftersun is my personal favorite of the year, Everything Everywhere All at Once is the film which best encapsulates the year. Watching this frenetic multiverse saga feels like living through 2022: overwhelming, oversaturated, tugged in too many directions to move. Evelyn feels it; so does Joy. That temptation to be rendered numb by the enormity of everything, to be swept up in the riptide of Casey’s endless scroll—it is so, so strong. Which is why we’re lucky to find people who grab on, who pull, who insist upon meaning despite a wave of convincing arguments to the contrary. What I love about Everything Everywhere is that it has no desire to make sense. It knows that to limit ourselves to rationality is to lay down our greatest weapon in the fight: our uncanny ability to hope against reason. Particularly when we’re hoping on someone else’s behalf. What we lack in the first person we give doubly in the second, life rafts anchoring life rafts, conjuring solid ground from scratch.

This is the gift we give each other: insisting that we matter. Reiterating us to us. We become each other’s legacies. We remember, we edit, we elevate, we gel. We bear witness to each other’s innermost monsters; we project them on a canvas, alchemize them into art. That proverbial tree that’s falling, of course its impact makes a sound. It’s surrounded; it’s a forest. Whether we cling through a thousand parallel lifetimes or exceed each other’s grasp, the bassline thrums. We’re a web of interconnected witnesses, studying, reverberating one another—and as long as stories are being told, we won’t be fully lost.

Here’s to one more year of stories.

Closing Bits

This site used to be a repository of my weekly film reviews, but in recent years my output has waned. Nowadays these Best-Of recaps have been pretty much it. Maybe my schedule has gotten the better of me, or maybe my bar for what should exist on my “permanent record” has simply gotten higher. Either way, I’m at peace with it!

But that doesn’t mean I’ve stopped watching movies or sharing candid thoughts. The Spoiler Warning Podcast is alive and well. Travel and sickness left the past year a bit more chaotic than usual, but we’re hoping to return to a weekly cadence soon. And while I don’t always include a review, I do log every film I see on Letterboxd. Much of the last year was spent filling in some 150+ blind spots from the 1960s and 1970s. In addition to exposing me to a shocking number of masterpieces, this also did eat into my contemporary film viewing—down from my typical ~120 to a meager 84. I’d make the same trade in a heartbeat.

Aside from my own hobbies, I’d like to use this space to highlight some amazing work being done elsewhere. On the podcast front, I’m a devout listener of Filmspotting, Fighting in the War Room, The Filmcast, and Blank Check. If you don’t listen, you’re seriously missing out. As someone who only manages to do this once a year, I’m continually in awe of folks who write movingly about film at a professional level: Walter Chaw, Marya E. Gates, and Robert Daniels are sources of weekly inspiration for me, and well worth your attention. In terms of broader cultural commentary, there may be no more eloquent voice on the planet than Emily St. James—wherever she lands next, I suggest you pay attention. Finally, I’d urge you to check out Akoroko, a new media initiative built to spotlight African cinema. I’m proud to support their work, and encourage anyone who is passionate about widening the field of view of film discourse to do the same.

See you in 2024!

-

Here’s The Process™.

Step 1: Jot down my favorite ~30 films in a formula-heavy Google Spreadsheet.

Step 2: Score them based on personal preference as well as their ranking on my previously-established Top 10.

Step 3: Generate 50-60 candidate pairs along with a one sentence description of what binds them, until every film from Step 1 has multiple points of entry on this list.

Step 4: Sort those pairings based on a weighted combination of the scores in Step 2.

Step 5: Throw those scores out the window and spend untold hours agonizing about every possible trade-off, until eventually it’s February, damn it, and I just have to suck it up and write.↩ -

If I had to rank these as a Top 20…which I’m not, and you can’t make me…it would probably look something like:

1. Aftersun

2. Everything Everywhere All at Once

3. The Banshees of Inisherin

4. TÁR

5. RRR

6. BARDO, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths

7. The Menu

8. We’re All Going to the World’s Fair

9. Bones and All

10. Resurrection

11. Fire of Love

12. After Yang

13. The Woman King

14. White Noise

15. All the Beauty and the Bloodshed

16. The Eternal Daughter

17. Saint Omer

18. Holy Spider

19. Emergency

20. Athena

But then what about the missing ones? Pinocchio! Marcel The Shell With Shoes On! Descendant! Cha Cha Real Smooth! This is why I don’t do Top 20 lists. ↩ -

Except Triangle of Sadness, which would have paired wonderfully with The Menu had I not loathed it.↩

-

“You already know the difference between the size and speed of everything that flashes through you and the tiny inadequate bit of it all you can ever let anyone know. As though inside you is this enormous room full of what seems like everything in the whole universe at one time or another and yet the only parts that get out have to somehow squeeze out through one of those tiny keyholes you see under the knob in older doors. As if we are all trying to see each other through these tiny keyholes.” – David Foster Wallace, “Good Old Neon.”↩

-

I know, I know, this isn’t explicitly a sequel to The Souvenir and The Souvenir Part 2. But it’s impossible for me to separate that Julie from this one, especially when the same actress plays her mother in all three films.↩

-

Zar Amir Ebrahimi, incredible here and even better in recent Sundance winner Shayda. She is a serious force to be reckoned with.↩

-

Far smarter people than I have written about RRR as a piece of nationalistic propaganda, a flawed retelling of history, etc. I have nothing to add to that conversation, except to say that my untrained eye interpreted every historical figure in this movie as a fictional superhero or villain, with Western Imperialism serving as the only real-world character. That guy deserves all the beatings he can get. ↩

-

Three words: take-home granola.↩

-

In a year that offered no shortage of films that saw the director turn the camera inward, I found BARDO to be the most entertaining on its surface and the most brutally honest, incisive. More inventive than The Fabelmans (which I very much liked), more damning than Armageddon Time (which I felt conflicted about). This is, to be clear, not a popular opinion.↩

-

To see just how easy a mark I am, consider a few of my previous number one picks: C’mon C’mon (2021), Honey Boy (2019), Eighth Grade (2018), American Honey (2017). Naturalistic independent dramas about growing up never fail to destroy me, particularly when there’s a fraught adult/child relationship at the center. This is, however, the first year my emotional Achilles heel has intersected with a broader critical consensus. Broken clock twice a day, etc.↩