Note: In addition to being a music-inspired memoir, this is also meant to function as a literal playlist! You can listen along on Spotify, Apple Music, or YouTube.

What Is This, And How Am I Supposed To Read It?

For me, music is almost entirely about memory. The songs that stick are always entangled with certain times and places. Some are great, others embarrassing—all inform who I am. So on March 19 2020, towards the beginning of shelter-in-place, I decided to embark on a challenge via this Twitter thread. Every morning, 7 days a week, I would share a song and a piece of writing about a memory it recalled. It would go “until this thing ends.” I assumed that meant two or three weeks. I had no idea what I was signing up for.

Still, a commitment is a commitment. So for 100 consecutive days, I followed a very particular routine. I would wake up before 7am, no exceptions, and write. Sometimes I’d have a draft or two saved up from the previous evening, and the morning would be an opportunity to polish. Others, I’d wake up with absolutely nothing. Regardless, the conclusion was the same: By the start of the workday, I would have some song paired with some memory, condensed into 2-4 iPhone-sized notes screenshots, and hit “Post.” There was no ability to edit, and it shows. The longer the project went on, the more complicated these stories became, and the more difficult it became to keep writing. Every week or two I contemplated quitting, certain I had run out of ideas. Those weeks, in hindsight, produced some of my favorite pieces.

The result is rather difficult to pin down. Is it a playlist, a creative writing experiment, a short story collection, a 50,000 word memoir? I can’t say; I’m still too close to it. I do know that it covers every year of my life from age 10 and up. I also know that it is, by virtue of memory, prone to wild inaccuracies—the errata alone could fill another 20,000 words. I also feel (though, again, I’m too close to it) that it gets substantially better as it goes along: While there are early entries I’m immensely fond of, I feel it wasn’t until Day 60 or so that I really settled on the style. You can be the judge. What follows is a lightly edited reproduction of the original thread.

A note on reading. These are mostly meant to be taken as independent stories, and shouldn’t require any prior knowledge (about the music or myself). Much like a playlist, there’s a certain emotional ordering to it: Almost every entry is somehow connected to the one that precedes it. Sometimes the connection is musical: a muffled preacher tying Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s “Static” to Julien Baker’s “Go Home”, the ending whirl of Neutral Milk Hotel’s “Communist Daughter” becoming the opening guitar riff of Death Cab For Cutie’s “Blacking Out The Friction.” Sometimes it’s thematic: a series of wedding-related entries (Song 33–39), two Valentine’s Days multiple years apart (Song 64 to Song 65), a week devoted to overthinking / authenticity amid the protests of the murder of George Floyd (Song 72–80, more or less). Many choose to shuffle their playlists, and this should mostly hold up to that. However, there are some sections where chronology is quite important: Songs 13–14, 22–23, 28–29, 69–70, 96–98.

My humble opinion is that you should read them in order, with one exception: I think to get a bit of context, you may want to start with Song 100 (which functions more as a summary / epilogue) and then loop back to the beginning. Ideally you’d have the playlist on in the background and your finger on the “Skip” button…but that is, admittedly, a lot to ask of a stranger on the internet!

Speaking of context, there’s no easy way to transpose a Twitter thread (with its ramshackle immediacy / sense of iterative building) into a blog post. I’ve tried to find a solution that is more readable than a series of screenshots, but still captures the real-time aspect. You’ll see call-outs:

To indicate my introduction to, or additional thoughts on, a piece at the time of writing. You’ll also see images, videos, and misc links that were posted with the text on the day of writing.

Finally, since 100 entries are quite a bit for a browser to load in one go, I’ve split this into multiple pages, 20 entries per page. You’ll find this pagination widget at the bottom of every page; or you can hit “All” to view a collated version (this is my personal reading preference).

Thanks, and happy reading!

Tiny tech detail: Every song can be indexed with an anchor link of the form “#SongXXX”. Song 65, for instance, lives in the “#Song065” anchor of both Page 4 and of the collated page.)

Artist: Sun Kil Moon

Date: March 19, 2020

Listen

Permalink

In 2007, I moved from San Diego to attend college at Berkeley. For the next few years, there was always a background hum of loneliness — some sense of impermanence, that “home” was forever 500 miles south. I found myself romanticizing freeways. I loved the idea that one contiguous stretch of asphalt separated me from my family and friends; that on any given night, I could hop on that conveyor belt and be surrounded by morning. 5 or 10 weekends a year, I would make up an excuse to do just that: wait till 10pm on a Thursday or Friday night for traffic to die down, fill up a pair of disgustingly large 7-11 travel mugs, spend 7 or 8 solitary hours on I-5, get home just before sunrise. Sunday always came too soon, and at 10pm I’d follow the same ritual in reverse.

Music meant a lot to me on those all-night drives. It made it feel like a spiritual journey, a sacred ritual, with a self-seriousness only college could allow for. And no slot in my playlist was holier than this: It’s for the moment on the return trip, after some 4.5 hours of Nothing But Cows, when the 580 snakes down a hill and all the lights of the Bay come bursting into view. That slot was for the happysad, the melancholy, the you’re-lonely-now-but-that-loneliness-is-good. And it was almost exclusively reserved for “Lost Verses” by Sun Kil Moon.

I came up from under the ocean

Evaporated sea salt water

A mist above the skyline

I haunt the streets of San Francisco

Watch over loved ones and old friends

I see them through their living room windows

Shaken by fear and worries

I want them to know how I love them so

Artist: Iron & Wine

Date: March 20, 2020

Listen

Permalink

It was fall of 2005, and I’d only recently gotten my driver’s license. The freedom felt amazing, and music was the perfect expression of it. First, because I could finally blare it. Second, because I could drive myself to a record store and (with my vast Dairy Queen riches) buy whatever album I wanted. I had a Sony CD player with a tape-deck adapter, a giant binder of CDs under the seat, and a smaller CD holder attached to my sun visor…for reasons I can’t even fathom, given the way San Diego sunshine & polycarbonate interact.

This is one of the earliest purchases I remember from those days: a collaboration between Iron & Wine and Calexico. I bought it the day it came out. This song, in particular, gutted me with its heart-on-sleeve simplicity. I remember driving to some secluded part of town that evening, cranking up the volume to some ungodly level, and setting it to repeat.

May my love reach you all

I’d lost it in myself and buried it too long.

Artist: LCD Soundsystem

Date: March 21, 2020

Listen

Permalink

Scrolling through the 80 or so candidates I jotted down for this list, I realized the vast majority of memories I associate with songs take place at night. Not just night, but very late at night—the freeway just before sunrise, a 2am trudge home in Tokyo, an all-nighter in a coffee shop in Singapore Airport after abysmally failing at some grand romantic connection. I’ll get to those.

Today’s memory is about all-nighters. Namely, the all-nighters I would do at least 3 times a week in the robotics lab at UC Berkeley in my junior and senior years of undergrad. Chalk it up to poor time management or sheer ambition, but I loved all nighters. I loved the way time seemed to dilate: I could end classes at 4pm, finish homework, grab a bite, show up to the lab at 7pm, and know that I had 14 hours of solid work time available to me before real life would set in again. Hard-to-reproduce bug in the laundry folding code? Experiment needed to be rerun? A conference paper was due tomorrow and I still didn’t have any tables filled in? No problem! I had infinite time at my disposal. The fancy espresso machine I’d guilted various professors into buying for our floor didn’t hurt, either.

Sometimes, around 4am, I would step away from the computer, make a cappuccino, and sit on the 7th floor balcony overlooking the Bay. This is the song I would listen to on repeat.

And if the sun comes up, if the sun comes up, if the sun comes up

And I still don’t wanna stagger home

Then it’s the memory of our betters

That are keeping us on our feet

Artist: CHVRCHES

Date: March 22, 2020

Listen

Permalink

It was September of 2016, and I’d found myself in London with a few coworkers (total coincidence, separate trips). It was Thursday night, and we all needed to be back in the San Francisco office by Monday. I was staring at maps and ferry routes, trying to square the circle on one obsession: I needed to get to Islay.

For the uninitiated, Islay is a tiny island off the west coast of Scotland. You may recognize it as the place Ron Swanson goes for his birthday on Parks and Rec. With its neighbor Jura, it’s known as the mecca of peaty whisky—”peat” being that distinctive smokey note you get when you dip into, e.g., an Ardbeg or Laphroaig or Lagavulin. All of those distilleries are centuries old, and all are on a single 2 mile stretch of road on the perimeter of Islay.

Coworkers were skeptical, but I hatched a plan. Three of us would fly to Aberdeen early on Friday morning. We’d rent a car and drive through Speyside and the Highlands, tasting along the way. One would get dropped off at Glasgow Airport on Saturday around 2pm for an early flight out, and the two remaining would continue westward to the port in Kennacraig, catching the last ferry of the day. We’d make it to Islay just in time for dinner, have a few good drams, pass out, and spend Sunday morning doing as many distillery tastings as possible before the 3pm ferry out. (I know that sounds crazy, and potentially reckless given the driving…but I’m telling you, there’s something in the air out there.)

Against all logic and reason, the plan worked flawlessly. I remember driving back to Glasgow that drizzly Sunday afternoon, rolling through idyllic little lakeside towns as we alternated stereo duty. This song by CHVRCHES is the one that sticks with me the most. The sun was setting in the most gloriously muted way, and I was filled with that preemptive nostalgia you get whenever you know a trip is coming to a close.

There is grey between the lines

Artist: Amy Grant

Date: March 23, 2020

Listen

Permalink

By starting this list with a few Pitchfork-friendly tunes, it might seem like I’m trying to cultivate some image of myself as having been remotely cool or ahead of the curve. Let me assure you, I was not. Picture a bowl cut, a lisp, and a T shirt that goes almost to the knees. The face you just conjured was my own.

This memory comes courtesy of the first album I really sank my teeth into: “Heart In Motion” by Amy Grant. Age unknown, though to save face I’m going to guess I was about 6 (honestly might have been 10). My mom had recently gotten a new Sony Walkman, and wherever we found ourselves — grocery store, YMCA for swimming or Tae Kwon Do lessons, an assortment of beige office buildings about which I only cared enough to retain the word “Errand” — I would be glued to a pair of comically large Sennheisers, blasting Amy’s controversial crossover sensation.

Others may have gone with the wildly more popular “Baby, Baby,” or perhaps the end-credits-in-a-90’s-romcom-worthy “That’s What Love Is For.” But I was no chump. I knew a real banger when I heard one. “Good For Me” was, and continues to be, one such banger.

Artist: Yo La Tengo

Date: March 24, 2020

Listen

Permalink

I’ve tried to limit myself to one song per artist in this list, but I’m gonna level with you: Unless this lockdown ends recklessly soon, Yo La Tengo is showing up more than once. They’re a band that I can’t seem to shake, lurking in the periphery for months or years at a time only to strike at precisely the right moment. “You know that particular mood you’re feeling? We’ve got an entire album dedicated to it.”

I discovered YLT in my Freshman year of undergrad. Like any musical discovery worth its salt, this one came on the heels of a breakup. It was a gloomy Sunday afternoon, and I’d just ended things with my highschool sweetheart. You know the story. You move away to college, learn a tiny bit about yourself, and realize you don’t have to be tethered to who you were at fifteen. Realize that maybe, just maybe, being vaguely content with a tinge of annoyance—making some teenage Archie Bunker face whenever teenage Edith speaks—isn’t the height of romantic possibility. You brush the thought aside, but it keeps creeping back, until eventually it all pours out in an extended argument about something wholly unrelated. A few tearful hours in the dorm parking lot, earnest promises to stay best friends (“just like Jerry and Elaine”), one last sight of her little red Honda, and you’re entirely on your own.

I didn’t want my new roommates to see me cry. So rather than head inside, I walked a few blocks to Amoeba Records, where I could aimlessly peruse the Used section while I gathered my thoughts. After a while, I noticed the music coming from the loudspeaker—hushed vocals, gently bobbing bass, tender and mournful and light all at once. It was a hopeful sort of melancholy I hadn’t experienced before, the sort where love sounds just a little bit sad and tragedy a little bit joyful. I asked the clerk what he was playing, and he handed me my first of many Yo La Tengo albums. I wore the metaphorical grooves out of this one that night.

So we’ll try and try, even if it lasts an hour

With all our might, we’ll try and make it ours

Because we’re on our way

We’re on our way to fall in love

Artist: La Dispute

Date: March 25, 2020

Listen

Permalink

So many great songs are about the beginning or end of a relationship, those times when everything feels so stark, so hugely consequential. Uncharted territories. An ongoing relationship, however wonderful, lacks that sense of hyperbole. So songs that deal with it often compensate by upping the stakes: I am the luckiest, the happiest, the most undeserving of the absolute perfection that is your beauty.

There’s a time and place for the cheesy stuff. But to me, love is rarely about superlatives or grand romantic arcs. It’s about a thousand quiet vulnerabilities, incidental intimacies; those conscious, continual decisions to open yourself and receive the other likewise, in (to crib from David Foster Wallace) “myriad petty, unsexy ways every day.” That everyday-ness is where “Woman (In Mirror)” resides.

This song has come in and out of my life, but the starkest memory I associate with it is from a couple years ago. My twin brother was getting married, and Joanna and I were down in San Diego for the wedding. We’d been dating a little over a year at this point, and we were staying in a tiny AirBnB. It was a retrofit pool house on one of those enormous properties that are surprisingly common in Southern California, and always euphemized as “upper middle class.” I had finished getting ready and was lounging around in a button-down and tie; Joanna was standing in front of a small circular mirror in a flower print dress, putting the final touches on her makeup.

In truth, I have no idea if I actually listened to this song while she did that, or if the two have simply intertwined over time.

There are moments here only yours and mine

Tiny dots on an endless timeline

Go on and on and on

All the motions of ordinary love

Artist: Matchbox Twenty

Date: March 26, 2020

Listen

Permalink

I don’t remember much about the first time I couldn’t breathe. I must have been 12 when I woke my mom up with the news. I don’t recall how it happened, but filling in the blanks from a lifetime of experience, I’m certain it was terrifying. Breathing is a bit like juggling: When you’re lost in the flow of it, it’s damn near effortless. Tweak a parameter just a smidge, though, or fixate on any constituent part, and that delicate equilibrium topples. Seems impossible from the start.

To this day, it’s scary when an asthma attack hits…if it even does hit, that is. The condition is so intermingled with the fear of the condition, I can’t truthfully tell you where one ends and the other begins: shortness of breath begets anxiety begets shortness of breath. At best it’s a darkly funny cycle; at worst it can be debilitating. It’s taken decades of medication (daily inhaler, albuterol for emergencies), lifestyle changes (cardio, intermittent therapy), and placebos (a constant supply of honey lemon Halls) to tilt the latter into the former—to truncate those 2-4 weekly asthmapanicwhoknows attacks into mild annoyances that are dead on arrival. Even still, some nights are worse than others, and the spectre of an acute respiratory pandemic hasn’t exactly helped. So I can only imagine how scary it felt that first time, back when it was all so new, so uncertain. That sudden loss of invincibility.

What I do remember, all too vividly, is the Urgent Care waiting room. It was a dramatic arc I would repeat at least a half dozen times: the rising tension of a sprint to the hospital culminating in bored, anticlimactic triage. Your vitals are fine; you aren’t wheezing too badly; sit down, kid, we’ll get to you when you can. There would be treatment (15 minutes with a nebulizer, a rote prescription for prednisone) but first came a solid 90 minutes of nothing.

It’s a strange thing to be simultaneously terrified and embarrassed, your id fighting for survival while your ego smiles apologetically. The longer I waited in that sterile, tiled Purgatory, the more it dawned on me that I was going to be fine. No one survives 90 minutes of “not breathing.” But it wasn’t a relief to be fine; it was a burden. Fine meant I’d wasted everyone’s time, made me the boy who cried “respiratory failure.” A flatlining medical device or sudden loss of consciousness might have given a doctor something to go on. Absent any drama, I could only feel crazy.

A TV hung in the corner of the waiting room, blaring what I assume was VH1. Would you believe me if I told you that, just as my fear-shame spiral was reaching its nadir, I heard Matchbox Twenty’s early-aughts anthem for the very first time? Truth be told, I’m not sure I’d believe me either. Sometimes memory, like shortness of breath, can be conjured from scratch. But it’s real to me now, and is there really any difference?

I’m not crazy, I’m just a little unwell

I know right now you can’t tell

but stay a while and maybe then you’ll see

A different side of me

Artist: Mumford & Sons

Date: March 27, 2020

Listen

Permalink

Continuing the trend of Things That Scare Me: I am mortified of public speaking. People are often surprised by this, because A) I do it all the time, and B) my primary crutch is to cultivate an easygoing demeanor. Don’t buy the facade. If you ever see me on stage, know that I am genuinely terrified of you. That terror never goes away, you just learn to mute it. Years of false alarms, paired with no shortage of coping mechanisms, have taught me to quarantine my panic, put the fight-or-flight instinct in a box.

In May of 2011, I had no boxes. I had spent all four years at Berkeley running from the monster. I only took classes which didn’t have a participation score; I did 80% of the work in any group project so the rest of my team would present to “make it fair;” on multiple occasions, I dropped a course solely because the word “presentation” appeared on the syllabus. Yet here I was in the final week of my senior year, pulling an all-nighter to re-re-re-rehearse the first public speech I would give since highschool graduation—not for a small class project or a buddy’s wedding, but for an audience of some hundred academics at an international robotics conference in Shanghai.

The breakfast buffet in the 54th floor lobby was in full swing, and I couldn’t dilate time any longer. It was about 7:45; my session started at 8:30. It’s not an exaggeration to say that my entire body was shaking, from nerves and lack of sleep and empty-stomach coffee. But I had to get moving. In less than one hour, I would be on stage. The notion wasn’t just scary, it was literally unimaginable: There in that windowed lobby I couldn’t string 5 words together without quivering. How would I make it through a single slide, much less 40? I imagined breaking down at that podium on the other side of the world, as all the top professors who’d seen “promise” in my application a few months prior suddenly recognized the fraud I’d always been.

It was hot on that walk to the convention center, and overexposed in a way that made the whole scene feel surreal—the city’s signature haze compounded with my anxious, swirling fog. As I levitated through the bustling city, pulled toward my inexorable death, I fumbled for the only thing I could control: the soundtrack. I don’t know why this song is the one I chose. Was it the motivational swell of the horns and banjo? The battle between two parts of oneself? The singalong vocals as a mini- support group? All I know is I had it on repeat all day: walking through the city, entering That Room, leaving hours later in a triumphant, slack-jawed daze.

Artist: The Hold Steady

Date: March 28, 2020

Listen

Permalink

This entry isn’t meant to funny per se, but neither is it meant to be a cautionary tale. It just is what it is: the story of my first blackout. Or, for you glass-half-full types, the story of my second-to-last blackout. (The last would come a year and a half later, involving a chipped phone, an empty wallet, and a surprise bill for an extended international call placed from Tokyo to San Diego. We’ll get there.)

The setting is St. Paul, Minnesota, May 2012. Same conference as yesterday’s entry, one year later. This time around, I wasn’t on the hook for a single presentation: My only directive was to learn and connect—”connect” being the euphemism professionals use to make drinking sound productive. I was in my early twenties and productivity was booming.

I don’t miss too much about academia, but I do miss the Conference Buddy phenomenon. The Conference Buddy is a hybrid between Old Friend and Acquaintance, someone you’ve spent time with on 3 or 4 continents who you would never so much as text back home. These particular Conference Buddies had closed out a bar with me. We compared notes on our schedules the following morning, said our goodbyes, and dispersed. I walked back alone, keeping the blurry Crowne Plaza logo continuously in sight, and I was nearly there when—well, I have no idea what happened next.

When I came to, I was a dozen blocks east and I was mid-conversation, hurriedly walking with Michael. Michael was an affable guy, maybe 35 or 40, who was guiding me to the nearest 24-hour ATM. He really appreciated my generosity: He’d lost his house after the disability checks stopped coming through, and my offer to buy him a hotel room was exceedingly kind. Yeah, no, we’re almost to the 7-11, anyway what was he saying? Robots. They sound so cool; he used to work in construction himself, and can only imagine how robots will change that.

If this sounds like it’s heading for disaster, don’t worry. Nothing happened. I pretended to know what the hell we were talking about; we made it to the 7-11 and Michael waited outside; I took out $120 (a small fortune in grad student currency) and handed it to him; we hugged and he pointed me back in the direction of the Plaza. I walked back alone, probably 3:30am at this point, trying to piece together what exactly had happened. I put in my headphones to temper the confusion, playing the band I’d been repeating the whole trip—The Hold Steady, because it was the Twin Cities and I am obvious. The streets were flooded with a dim, orange light, and it all felt perversely spiritual in a way I can’t explain. Like recklessness and guilt and excitement and love.

We gather our gospels from gossip and bar talk

And then we declare them the truth

We salvage our sermons from message boards and scene reports

And we sic them on the youth

Artist: Cat Power (a cover of The Velvet Underground)

Date: March 29, 2020

Listen

Permalink

It was summer of 2007 and our road trip was coming to a close. Over the last two weeks we’d driven thousands of miles. Our first stop had been Vegas to link up with the girls’ trip. Then, armed with printed MapQuest routes and $15 per diems, we five teenage nomads pressed on. It was a straight shot through Utah to Boulder, CO, followed by a camping stay in Garden of the Gods. Detour up Pike’s Peak and on to Santa Fe, feat. what many agreed was the best pizza of our lives. Hours wasted in Albuquerque in search of a record store; an evening in Flagstaff perusing used books; a hike around Grand Canyon, South Rim, sunrise; an eerie night in Phoenix, whose downtown could best be described as “post apocalyptic.” It was a season of inside jokes and faux disagreements, urine-filled bottles and sun-baked bacon cheeseburgers, dusty tents and cramped Best Westerns and long swaths of asphalt overflowing with nothing. It was coming to a close.

We woke up before sunrise in a suburb of Phoenix and loaded the van for the very last time. It was a 5-hour sprint to Escondido if you stuck with the interstate, but that hardly seemed like a fitting end. We opted instead for the scenic route: the one that dips south around Blythe, sweeps by the sand dunes just east of Brawley, and winds its way through the Anza-Borrego Desert before eventually hitting home. I don’t know how we agreed on it, but I know it was unanimous. College would be starting in about a month, and try as we might, the group would never be the same.

The whole trip had been a goldmine of transcendent music moments, but none more beautiful than this: listening to The Covers Record in virtual silence, rolling through the desert as sun peeked above the hills, the five of us left with nothing to say as we staved off adulthood for a few hours more.

Oh I do believe

In all the things you see

What comes is better than what came before

Artist: The Mountain Goats

Date: March 30, 2020

Listen

Permalink

In Song 6 I wrote about my first breakup. And while the description was technically true, it only gave partial information. It detailed a more or less mutual decision, a clean separation, with evergreen promises to stay Jerry and Elaine. It didn’t mention that I would change my mind a week later, after the loneliness had time to really sink in. Nor did it include the months I’d spend clumsily putting back together the pieces of her trust, with half-felt reassurances and desperate escalations, only to inflict far more pain when it inevitably collapsed. The first had lent itself to catharsis, certainty. The second time around it was an uglier sort of grief, tinged with a sadness that felt murky and wrong. She had a right to mourn, not me. I was the selfish one, the perpetrator of a preventable hurt.

The least I could do, I decided, was give her space. So I withdrew from our group of friends almost entirely: They were her support system now, not mine. I spent a lot of time alone that first summer home from school, and what little social life remained was focused on the college group at church. I loved that there were new people there, ones who knew me solely as a Me rather than half of an Us. They gave me space to carve out a new identity, some hybrid between the persona I’d cultivated growing up in the church (the Extremely Earnest Guy, the perennial Good Friend) and the one I was awkwardly trying on up north (the Brooding Intellectual, the One With Good Taste). Looking back, I can trace a clear line from that patchwork of identities to the adult I eventually became. Glimmers of my authentic self started to peek through.

It took a few months. But eventually the guilt and tension dissipated, and the old cleansing feeling—that distilled brand of sadness that was allowed to feel good—took its place. She was okay and I was okay, and I re-entered my friend group just a little bit changed. The Mountain Goats had been a favorite of mine for years at this point, but one album, Get Lonely, had always been too devastating to touch. Now I couldn’t get enough of it. This song in particular became my rallying cry:

The wind began to blow, and all the trees began to pant

And the world, in its cold way, started coming alive

And I stood there like a businessman waiting for the train

And I got ready for the future to arrive

Artist: The Acorn

Date: March 31, 2020

Listen

Permalink

The hardest part of grad school is also a perk: There is zero separation between life and work. Usually this is emotionally draining, lulling you into a cycle of 14 hour workdays and 7 day weeks. But it cuts both ways, if you let it. You learn to cobble together a life out of the things you do “for work,” and if you play your cards right, life can be pretty fantastic—spending days honing personal skills, hosting visiting professors over Michelin Star meals, taking advantage of near-infinite excuses to travel. It’s the only time I’ve ever had truly guilt-free vacations. I was never on or off the clock; there was no clock.

In July of 2012, my labmate and I attended a conference in Sydney. As with all good conference trips, we’d left a few free days at the tail end to sightsee. After considering the Barrier Reef (“too obvious”) and the Blue Mountains (“too many Drop Bears” the locals insisted with a straight face), we settled on New Zealand. So we flew into Christchurch, ditched our camper van near Nelson, took a water taxi 40 km north, and embarked on a three day hike down the Abel Tasman trail.

The backpack was heavy and I was very out of shape, but it was worth it. I recall waterfalls and jutting cliffs and large flightless birds; deep blues and greens fading into impossibly dark nights; glorious sunsets and freeze-dried “fish pies” and Pinot by the fire with an orchardist named Bruce (whose “papples,” a cross between apple and pear, we’d find waiting for us in a goodie bag the following morning). I’d been carrying so much anger for the better part of a year, but it all felt so petty amid a world that was good. I had to let it go.

In a tent on the beach, I wrote a note to myself, describing a sense of “chocolate tranquility.” I don’t know what it means, but I know how it felt, and I remember the song that was stuck in my head.

One by one the seasons change you

Maybe once but not for all.

Artist: David Bazan

Date: April 1, 2020

Listen

Permalink

When I sketched out a plan for this series, this entry wasn’t on the list. If I’m honest with myself, it’s a bit painful to dwell on. Not because of the song (which is still the best sort of heartbreaking) or the events it conjures (which were completely unremarkable), but because of who I remember being at the time I listened. Or, to be generous, who I’d let myself temporarily become. This song transports me to a particularly ugly headspace. It isn’t a flattering look. Then again, this project wasn’t meant to be flattering.

In yesterday’s post, I mentioned the anger I was carrying as I hiked around New Zealand. As with so many emotions that feel insurmountable till the moment you clear them, this one had sprung from a breakup. The details don’t matter: She was a person, I was a person, what usually happens happened, and now I was a wreck. Blame it on the denial that comes after wishful thinking—on the toxic conviction of young men everywhere that love is awarded based on merit, a commodity they are owed, some moral contract bound by duty or by guilt. How dare she leave me, after all the things we shared! All the promises we’d made; all the hope that I’d invested. Songs I claimed to understand couldn’t have spelled it out more clearly: “You wanna fight for this love, but honey you cannot wrestle a dove”— The Shins; “Why do we keep shrieking when we mean soft things?” — Magnetic Fields. Yet there I was, fighting for a future that was never mine to own. Shrieking about injustice, the “betrayal” of soft things. The answers I “needed.” The closure I was “due.” Those phony, feral howls of the self-appointed Nice Guy, when romantic gestures fail and he feels the limits of his cage.

All that contempt, which hindsight has turned inward, was at this point in time trained exclusively on her. I ranted my version of events to anyone who would listen; I spent hours drafting e-mails I would (thank god) never send. I treated my heartbreak like a puzzle to be solved or a case to be litigated: replaying every moment in excruciating detail, trawling social media for exhibits or for clues. Imaginary shouting matches with grand rhetorical conclusions, repeated like prayers. As if love could be persuaded by an ironclad syllogism; as if shouting could be anything but proof that she was right; as if a heart needed proof. I experienced something which had never happened to me before, and which I’ve refused to let happen since: I fell asleep angry and woke up angrier. My bitterness was all-consuming, hateful, and deeply, deeply wrong.

Music was a means of exorcism in those days, and mine was a full-body anger an acoustic guitar couldn’t channel. I bought a 76-key Yamaha and tried to revive what little technique I’d learned as a kid. I spent hours scrutinizing David Bazan’s live piano rendition of “I Never Wanted You,” fumbling through an arrangement till it was close enough to draw blood. Over countless nights to come, I would follow this routine: Plug in headphones, max out the volume, and bear down on my misery while singing in a whispery-wail—silent to any neighbor, full blast in my mind.

You know we never connected

You only thought we did

But baby I was faking the whole time

Artist: Pedro The Lion

Date: April 2, 2020

Listen

Permalink

When I wrote about Yo La Tengo, I mentioned that some bands seem to weave in and out of my life. With David Bazan, there’s no weaving necessary. Line up the arc of his music against the arc of my life and, give or take a few years’ offset, it’s a nearly perfect match. In Junior High it was all about Pedro The Lion, the Christian indie darlings who sang earnestly about doubt without losing their sense of hope (Whole, Hard To Find A Friend, The Only Reason I Feel Secure). In High School they’d morphed into an edgier, concept-driven group, musing about life’s darker aspects and the hypocrisy of the church (Winners Never Quit, Control, Achilles Heel, Headphones). College began with Bazan dismantling the band; I and his solo EP were now decidedly more ambiguous, filled with a complicated mournfulness that was better felt than explained. At the tail end of undergrad came Curse Your Branches, Bazan’s searing rejection of the faith of his youth—a fiery “breakup with God” that I told myself at the time was a cautionary tale rather than precisely where I was headed. Denial is a drug, but it doesn’t last for long. My wrestling with the theological soon gave way to the political, followed by a time of contemplation, punctuated by sadness, culminating in an acceptance that made all that wrestling feel absurd. Strange Negotiations, Blanco, Care, his final re-emergence as Pedro The Lion. There’s a reason I’ve followed him through two decades of monikers, from packed concert venues to intimate living room shows. It runs too deep to be objective: We became finite together.

Back in Junior High, I had no sense of what the future held. I only knew that there was a gnawing gap between the person I aspired to be and the person I knew deep down. Outside: Bible studies, mission trips, fierce arguments about Calvinism; a hardcore Church Kid in every respect. Inside: struggles of passion, thoughts I “knew” to be sins, and the occasional flare-up of one terrifying thought. That nothing was certain. That the scaffolding around which I’d constructed my eternity might not bear all this weight. That I might lose everything. Don’t misunderstand me. I fully believed, and have mortifying receipts all over the Internet Archive to prove it. I just couldn’t reconcile my heart with what I thought my mind knew. Couldn’t explain why this thing of which I was so certain felt so…cheesy?…spoken aloud.

I used to bawl my eyes out to this particular tune. “Secret of the Easy Yoke.” At the time, what overwhelmed me was that unthinkable confession, the thing we felt but dare not say:

I still have never seen You

And some days

I don’t love You at all

Today I smile at the release of it all, our prophetic letting go:

Peace be still

Artist: Club 8

Date: April 3, 2020

Listen

Permalink

In spring of 2017, I found myself in Wuhan on a last minute work trip. Or I should say I found myself in the Hubei Province: as with many major Chinese corporations, the HQ I was stationed at was pretty far removed from any metropolitan center. You get the distinct sense, when visiting these places, that a branch of a large company creates a city unto itself, an isolated cluster of hotels and residential buildings that exist solely to prop up visitors and staff. This sort of phenomenon can be found just about anywhere (as any visit to the Rust Belt can attest). But the sheer scale of infrastructure in China, paired with my total lack of Mandarin, served to heighten my sense of isolation.

The first few days were an emergency, hence the frantic redeye out. But once a plan was settled and teams were set in motion, there wasn’t much left for me to do but wait—for their devs, for mine, for any new fire that might crop up. I couldn’t really leave, but neither could I help; that awkward, urgent impotence shared by managers around the world. Twiddling my thumbs in the client’s office felt intrusive, so I started passing days in the hotel room alone.

Like many business hotels in East or South Central Asia, the one I’d holed myself up in was almost impossibly nice. Immaculate suites, labyrinthian buffets, a Bellagio-esque foyer (fountain very much included). It was in a recently developed area, and off-season to boot, which cast the entire experience in a Truman Show light: The place was comically enormous, and I had it almost entirely to myself. If I wandered the hallways, I would only see staff; if I went to the gym, one employee would check me in, another would hand me water and a towel, and a third would offer to help me stretch. The feeling extended to the surrounding area. Lovely, maintained garden paths with nobody walking them. Luxury homes in all directions and not a single car.

This memory is of Hubei, but it’s a stand-in for a phenomenon I’ve experienced many, many times. It goes like this: You race to finish the [project, presentation, paper, deal], and for a brief period you tell yourself the whole world hangs in the balance. You say it first as a mental trick, but eventually you start believing it. The goal subsumes everything; it blots out the sun. Then, just as you really feel you’re hitting your stride, it’s done. You’re transported back to a mundane everyday-ness you’d spent manic weeks forgetting. It’s a funny sort of relief, that whiplash, and it carries with it the tiniest ache. A hint that it was always mundane, your racing included. That the cycle never ends and it’s likely for the best.

I remember those days fondly, when everything suddenly slammed against nothing. I would sleep in till noon, zone out to Netflix, and pace the gardens of my bespoke sanctuary while listening to this song.

Fool me into believing

I don’t care if you’re deceiving me

Artist: Damien Jurado

Date: April 4, 2020

Listen

Permalink

There’s something I associate with my early 20’s, which to this day I don’t quite know how to explain. It’s the unique blend of emotions I’d feel when driving at night with a girl sleeping beside me. Put in words it sounds chauvinistic or obliquely romantic, and in truth that may have played a part—some bone-deep urge to feel protective or needed after years of being taught that my role was to lead. Have at it, Freud. But significant others, good friends, acquaintances—it really didn’t matter, and I never interrogated it. All I know is that it made me feel special every single time, like some small measure of vulnerability was being entrusted to me. There’s no other way to say it, it was tenderness that I felt. Platonic (to my knowledge!) but tender just the same. Maybe with male friends I felt I didn’t have permission to recognize it as intimacy, to call those gestures acts of love: their easy breathing, slumped against the passenger-side door; my quiet sips of coffee, eyes glued to the road.

There’s a reason so many movies take place on road trips. Long drives bind us together, even if only briefly. They evolve like tiny, self-contained relationships: from clumsy silence to small talk to genuine conversation to a second, deeper silence that comes from knowing it’s allowed. From “What do I say?” to “Why say anything?”; similar in outcome, worlds apart in meaning. You don’t always get there, in the real or highway variant. But if you do, it’s more memorable than volumes of intended heart-to-hearts.

Some drivers use loud music to keep them awake. I preferred music that fit the occasion. If it was a long, overnight drive (as it so often was), the playlist had to sound like a darkened interstate feels: a soothing sort of melancholy, wistful, open-ended. Damien Jurado fit like a glove. When conversation petered out and only one of us remained, I would throw this album on, set the volume even lower, and take solace in everything I knew or imagined the silence to imply.

She walked in with sadness in her eyes

I could tell she’d been sleeping with the stars

Well hello, I am Dawn

Artist: Ben Folds

Date: April 5, 2020

Listen

Permalink

One exchange from Magnolia has always stuck with me. It occurs near the end of the film, when Donnie (William H. Macy) finally unburdens himself to Jim (John C. Reilly). The child-prodigy-turned-emotionally-stunted-adult has just taken a nasty fall, a botched step in a scheme meant to make him incrementally more attractive. Bloodied and humiliated, he exclaims to the officer: “I really do have love to give! I just don’t know where to put it.”

When I reflect on my adolescence, that’s exactly what I see: A shy, awkward whiz kid struggling to find footing, bursting at the seams with too much hypothetical love. In Junior High I had no clue what it was I was searching for—I’d never so much as held a girl’s hand. But I felt, at my core, that I was missing something vital. Everything I did, from music theater to church group to hours spent online, was suddenly a vehicle for longing. I was no longer the Tin Man learning his lines, I was the guy who might make Dorothy notice him. If I stood up during worship, I did so in an attempt to appear “deep” to onlookers. Late night chats on AIM, which had opened me to countless co-ed friendships, suddenly involved a scoreboard. How many laughs had I gotten in group chat? Was there any inside joke from which I risked being excluded? Had she signed off with a heart emoji or simply said “goodbye”—or better, had she deployed one of the Holy Trinity of acronyms, sought by “Best Friend”s far and wide? ILY (I love you). LYM (Love ya much). LYLAB (Love you like a brother). Usually it was the last one, and it would take years of unreciprocated crushes to teach me to take the “LAB” at face value. Back then, I was blinded by the letter at the start.

It’s tempting to draw a straight line from this love-hungry adolescent to Song 14’s spiteful ex. Hope as a sort of contrapositive resentment: if I put in more of myself she might love me –> by not loving me she therefore negates who I am.

Those early habits may have curdled somewhere, but today I’m choosing to cut the kid some slack. I don’t think this bowl-cutted, pre-teen Casanova was really after romantic love at all. He put his longing in that box because it’s the only kind he knew; it’s what every song was selling, what his newly coupled friends were giving constant, rave reviews. I watch him from a distance, now, this boy straining every muscle to connect. The beat his heart skips after a scripted hug from Dorothy; the flutter of excitement when someone types the letter “L”; the naive optimism he carries as he pedals all across town, racing towards this FroYo trip or that mall get-together, things he has no desire to join but is somehow terrified to miss. The way he does every little thing for an imagined audience: alone at his mom’s piano repeating the same arpeggios in D, crooning about his not-yet luck to some faceless, future You. What he’s aching for in that moment has nothing to do with romance. It’s to be validated, understood, seen.

And in a white sea of eyes

I see one pair that I recognize

Artist: The Tallest Man On Earth

Date: April 6, 2020

Listen

Permalink

I had a different post lined up for this morning. Then I woke up to an “11 Years Ago Today” memory on Facebook, and decided I had to switch gears. It’s a video of me at 19 years old, playing an acoustic guitar and singing. Somehow I’d found the strength of will to post it, unedited, to a social network that included some 300 friends, exes, crushes, classmates, teachers, pastors, my mother, my grandparents—even my roommates, who at the moment of recording were certainly away at class, and near whom I would never have been caught dead singing face to face.

I watch that video now, from this world before Likes and encouraging reactions, from back when every post began with an adjective to follow an implicit “Stephen Miller is…,” and I try to remember: What prompted me to do this? I didn’t like performing. This was during that stretch of time when I refused to take any course with a participation grade for fear of speaking up. It surely wasn’t meant to impress anyone. Honestly, I think I did it simply for the love of the song, a joy of discovery I’m not sure I still possess.

On April 5, 2009, I was driving with my roommates around midnight, when one of them put on an artist I’d never heard before. It was Swedish singer-songwriter Kristian Matsson, who goes by the stage name The Tallest Man On Earth. It was love at first listen. I adored his voice, laden with gravelly yelps like some tortured, Appalachian Dylan. I admired his guitar-work, a breakneck fingerpick that did the work of three instruments at once: gliding melodies at the fingers, pulsing bass at the thumb, audible creaks and scratches that formed a sort of accidental percussion. And the lyrics—they had this feral, overgrown quality to them. Americana as a sort of gnarled found art, broken and reassembled by someone an ocean away.

That next day, I returned from class and got to work. No complete tab yet existed of this song, but someone had at least worked out the tuning and a few essential fingerings: a crucial step, given his unorthodox playing style. I remember listening to the song’s first few bars over and over and over, playing at a snail’s pace till muscle memory eventually started to kick in. It’s the sort of twisty rhythm which sounds effortless sped up but feels impossible in slow motion; a precarious machine always on the verge of toppling over. I never came close to mastering it: it’d be more accurate to say I sprinted behind it. Wound it up, unleashed it, and hoped my singing voice could keep pace.

On April 6, 2009, I posted the video. It’s a one-and-done performance, shot from the neck down by a point-and-shoot Canon propped on a pile of textbooks, of “I Won’t Be Found by The Tallest Man In the World [sic].” In a sense, it’s as embarrassing to watch now as it must’ve felt moments after sharing: the twangy, scraping bass string of my beat-up Baby Martin, my quivering voice lagging as I fumble for the words. But it also makes me feel so good, to be reminded of the me that made it: the focus, the energy, the insistence on making my mark.

Deep in the dust forgotten, gathered

I grow a diamond in my chest

Artist: Okkervil River

Date: April 7, 2020

Listen

Permalink

Last Spring, Joanna and I found ourselves on the road in South Carolina, en route to a family wedding. The plan had been to take a redeye to Charleston, spend a day exploring her old stomping grounds, and drive a rental out to Myrtle Beach in the morning to arrive hours before the rehearsal dinner. Since there’s no way to make a day’s worth of rerouted flights sound interesting, you can simply take my word that things did not go as planned.

We were racing down the highway somewhere between Charleston and Myrtle Beach, having driven far more miles (and slept far fewer hours) than we’d originally intended. I was at the wheel with coffee; Joanna was in the passenger seat, drifting in and out. The Lowcountry, she’s told me, is prone to sudden, heavy storms. If my bare foot on the pedal (soaked shoes drying in the back) wasn’t proof positive, the fresh torrential downpours that came with each new mile marker served to hammer the geography lesson home.

It was the one of those highways that cut through the center of small towns, provoking a meditative cycle of fast and slow, freeway and stoplight. The sort that gives you the tiniest glimpse of a hundred scattered places, decelerating for a moment to parse out stray details, then hurtling to the next one to remind you of the scale. Living in a major city with an entire life in walking distance, it’s easy to forget just how spread out the US is.

On drives like this, I’m reminded that every town is a hometown, every street sign a neighborhood, every highway-side Waffle House someone’s vital social hub. I remember Escondido, and the small strip of freeway it grazes in contrast to the mental space it holds. How massive the distance from two consecutive exits had once felt; all the emotional mile-markers scattered on the side streets in between.

Okkervil River was coming to the Bay in about a month. Given the hallowed status they once held as my Favorite Band™ (in that five year stretch of time when such labels truly mattered), I had taken it upon myself to organize a large group of friends to go. I’d even made a playlist to convert those friends, filled with songs that used to mean so much to me which I hadn’t thought about in years. I floated in those memories as we barreled through the flood, whizzing past the grey outlines of other peoples’ lives.

The heart wants to feel, the heart wants to hold

The heart takes “past Subway, past Shop and Stop, past Beal’s”

And calls it “Coming home”

This is page 1 of 5. Use the widget below, or go to the next page, or view all combined:

Like most worthwhile ideas, this first one sounds exceedingly obvious: beyond all layers of theory or numb abstraction, when we talk about socioeconomic issues what we’re really talking about is the behavior of people—individuals with irrational feelings, desires, egos. So it stands to reason that small groups of people, brought in close proximity, might embody the same polarizing characteristics we see in our politics.

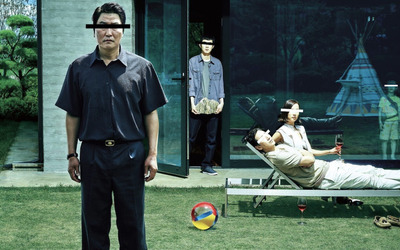

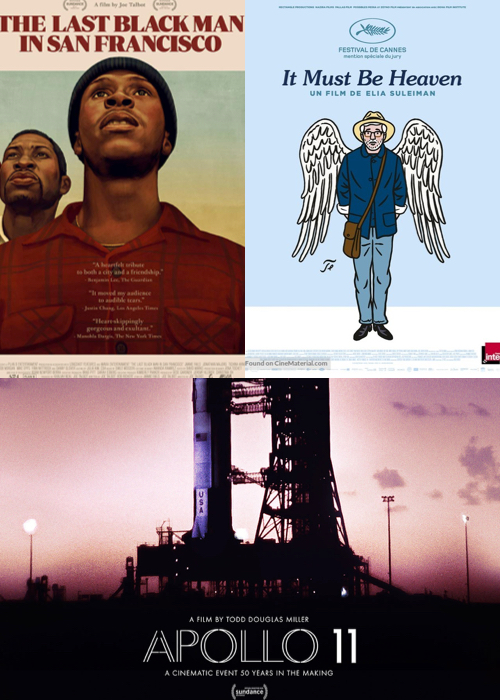

Like most worthwhile ideas, this first one sounds exceedingly obvious: beyond all layers of theory or numb abstraction, when we talk about socioeconomic issues what we’re really talking about is the behavior of people—individuals with irrational feelings, desires, egos. So it stands to reason that small groups of people, brought in close proximity, might embody the same polarizing characteristics we see in our politics. While a small group of people can reflect society at large, they don’t always reflect it accurately. Particularly when they’re buffered from the outside world. Three films this year used very different tacts to show the way

isolation begets a sort of funhouse mirror, creating a dangerously warped image of reality. Empathetically depicting that distortion field without excusing those who act on it is an inherently risky endeavor. So it shouldn’t be surprising that each of these was met with polarized reactions—often outright controversy—on initial release.

While a small group of people can reflect society at large, they don’t always reflect it accurately. Particularly when they’re buffered from the outside world. Three films this year used very different tacts to show the way

isolation begets a sort of funhouse mirror, creating a dangerously warped image of reality. Empathetically depicting that distortion field without excusing those who act on it is an inherently risky endeavor. So it shouldn’t be surprising that each of these was met with polarized reactions—often outright controversy—on initial release. If art is in constant conversation with society, and society is influenced by the art it consumes, a prolific artist might live long enough to be on both sides of the conversation. In 2019, we saw that phenomenon play out onscreen. Three iconic (and heavily-imitated) directors not only released their best films in years, they grappled with their own creative legacies in the process.

If art is in constant conversation with society, and society is influenced by the art it consumes, a prolific artist might live long enough to be on both sides of the conversation. In 2019, we saw that phenomenon play out onscreen. Three iconic (and heavily-imitated) directors not only released their best films in years, they grappled with their own creative legacies in the process. Still, there’s a reason we glamorize bad behavior: it’s riveting. Whether television celebrity or problematic friend, there’s a certain charisma or allure that comes with damaging behavior. In small doses, that allure can be a vehicle for empathy. Give it too much power, though, and it might pull you down with it.

Still, there’s a reason we glamorize bad behavior: it’s riveting. Whether television celebrity or problematic friend, there’s a certain charisma or allure that comes with damaging behavior. In small doses, that allure can be a vehicle for empathy. Give it too much power, though, and it might pull you down with it. You could make a case that art always hangs around the periphery of death, a subject so universal it’s become a cliché. This year, though, a much more specific idea about mortality was percolating. It has something to with coming to terms with ending one’s life: with rendering it, on some level, a positive choice. And sharing that happysad burden.

You could make a case that art always hangs around the periphery of death, a subject so universal it’s become a cliché. This year, though, a much more specific idea about mortality was percolating. It has something to with coming to terms with ending one’s life: with rendering it, on some level, a positive choice. And sharing that happysad burden. Human connection can’t slow death. Nor can it fix a broken world, cheery slogans notwithstanding. Love has never been an antidote for pain. At its best, though, it can sometimes be a means of sanctifying pain, of rendering shared hardship into a sort of testimony. Four films this year explore the way love can act as a bulwark of warmth against an uncaring world.

Human connection can’t slow death. Nor can it fix a broken world, cheery slogans notwithstanding. Love has never been an antidote for pain. At its best, though, it can sometimes be a means of sanctifying pain, of rendering shared hardship into a sort of testimony. Four films this year explore the way love can act as a bulwark of warmth against an uncaring world. Companionship is a powerful drug. When it’s working, a relationship can ground us, orient us, like nothing in the world. But when it’s misaligned, that same force can prove extremely destabilizing.

Companionship is a powerful drug. When it’s working, a relationship can ground us, orient us, like nothing in the world. But when it’s misaligned, that same force can prove extremely destabilizing. Filmmaking, like macroeconomics, has a certain built-in time delay—with so many variables between concept and execution, it’s hard to trace any neat causal links. So I don’t know when this particular sentiment started; I only know that it hit 2019 like a third act flash flood. It goes like this: unconstrained capitalism is a soul-numbing force.

Filmmaking, like macroeconomics, has a certain built-in time delay—with so many variables between concept and execution, it’s hard to trace any neat causal links. So I don’t know when this particular sentiment started; I only know that it hit 2019 like a third act flash flood. It goes like this: unconstrained capitalism is a soul-numbing force.  In a list with no shortage of tenuous connections, this one is the hardest to pinpoint. I’m struggling to put it in words. It isn’t an idea so much as a sensation; a very particular angle of approach. And it has something to do with longing. How certain spaces, when properly framed, seem to call to you even as they push you away. How they carve some entrancing middle ground between attainable and not, instill in you an irrational, pre-emptive nostalgia. It’s no surprise that these films are among the most visually sumptuous of the year. Every still could be a painting. Every painting makes you want.

In a list with no shortage of tenuous connections, this one is the hardest to pinpoint. I’m struggling to put it in words. It isn’t an idea so much as a sensation; a very particular angle of approach. And it has something to do with longing. How certain spaces, when properly framed, seem to call to you even as they push you away. How they carve some entrancing middle ground between attainable and not, instill in you an irrational, pre-emptive nostalgia. It’s no surprise that these films are among the most visually sumptuous of the year. Every still could be a painting. Every painting makes you want. In last year’s list, I saw cinema as a response to trauma—whether an escape, a confession, or an act of defiance. Maybe that was still rattling around in my skull when I sat down in theatres this year. Because for me, in a year jam-packed with fantastic films, the ones that moved me most felt less like storytelling than therapy sessions, working out the damage done by deeply flawed men. Each carried with them a collective exhale; a recognition that, by confronting the past head-on, we might eventually move beyond it.

In last year’s list, I saw cinema as a response to trauma—whether an escape, a confession, or an act of defiance. Maybe that was still rattling around in my skull when I sat down in theatres this year. Because for me, in a year jam-packed with fantastic films, the ones that moved me most felt less like storytelling than therapy sessions, working out the damage done by deeply flawed men. Each carried with them a collective exhale; a recognition that, by confronting the past head-on, we might eventually move beyond it.