More ramblings: Check out my six previous end-of-year lists to get a sense of my taste in movies.

Podcast: You can listen to my flat Top 10 list on The Spoiler Warning.

Introduction

I’ve looked at this from every angle, and I’m finally going to call it: There is absolutely no way to start a 2020 recap without some hackneyed platitude. So screw it, let’s play the hits. Communal: “Well, we made it!” Understated: “It’s been a weird one.” Conflicted: “It was simultaneously the least and most memorable year of my life.” Contemplative: “We were never more isolated, yet somehow never more connected.” Glib: “It was the worst of times, it was the worst of times.”

The truth is that even unprecedented events trigger predictable responses. Digging through my own year end writeups, I see a few recurring trends:

Here’s a hot take for you: 2016 was a rough year.

2017 was a year of complicated emotions. But if there was one universal mood which overwhelmed all others, it was this: a feeling of outrage—a desire to do something—with nowhere of value to funnel it.

I won’t speak for anyone else, but I felt drained by 2018…But as the headlines kept coming, my anger felt impotent; my sadness turned hoarse and performative. What was I supposed to do with all that heaviness?

I was angry, often, in 2019—glued to a screen when I should have been sleeping, seething with hypothetical arguments and blistering rebuttals. I was also extraordinarily happy in 2019, both in the Instagrammable sense and the more important, lived-in variety. I learned, somehow, to be both more and less certain of things. Or maybe it was to never pit one type of certainty against another, deeper type; to find more stable footing amid the not-knowing.

Still, predictable epiphanies are no less impactful. 2020 cut through the artifice and took them all out for a spin. Abstract moral quandaries become intimately personal. Political divides were somehow more searingly pronounced. Impotent outrage, performative sadness, hypothetical arguments in search of an outlet? Pack a lifetime of pressures into a few hundred square feet, stand back and wait for the blast.

Living in a city, our connectedness struck me as a blessing and a curse. I have never been so acutely aware of just how many people occupy my 10 block radius. My specific postal worker, the grocer on the corner, the cashier at the Burmese spot that feeds me once or twice a week. The skateboarders who transform my evening walk into a game of Biowarfare Frogger. The packed MUNI bus I’d once sprint across the street to catch, from which I now sprint across the street to actively avoid. The fiancé (née “girlfriend”) who has been my constant, sole companion. If I were an island, I’d have been entirely safe from harm…until keeling over from malnutrition around the third week of March. I am thankful that I am not, and will never be, an island.

I haven’t seen a single film which was conceived in the pandemic, yet I’m incapable of viewing cinema through any other lens. Of the 93 new releases I caught this year, 86 were in my living room, including all but one entry on this list.1 That context is impossible to ignore; it permeated everything. Virtual TIFF premieres became private celebrations. Purely visual spectacles were rendered hollow, insufficient. My phone became a constant, irrational distraction, and only a rare work of art could keep my anxieties at bay. As with every other aspect of my life, subtext was promptly upgraded to text: Now more than ever, I required a steady drip of pathos. Luckily, there was plenty of the good stuff.

So today I’m embracing my lack of nuance and counting down 10 thematic pairs2—reflecting 10 lessons that needed reiterating in this memorable, unmemorable, connected, isolated, predictably unprecedented year:

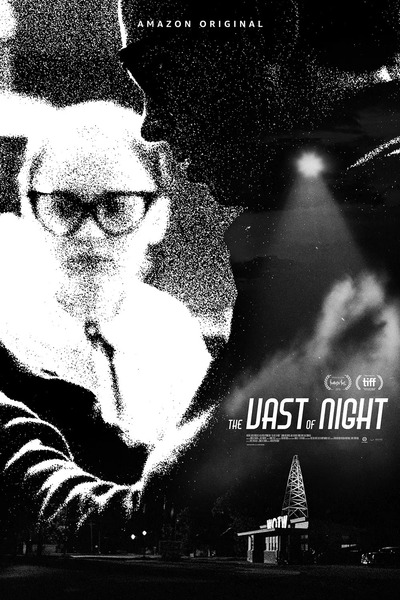

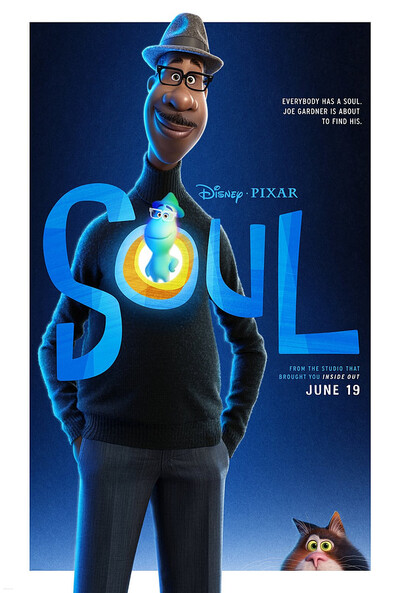

10: Cultivate curiosity: The Vast Of Night and Soul ↯

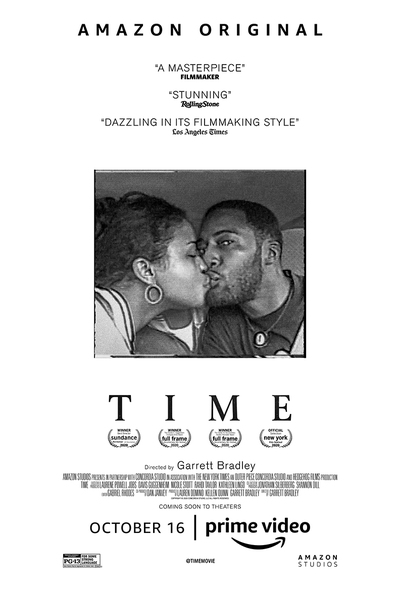

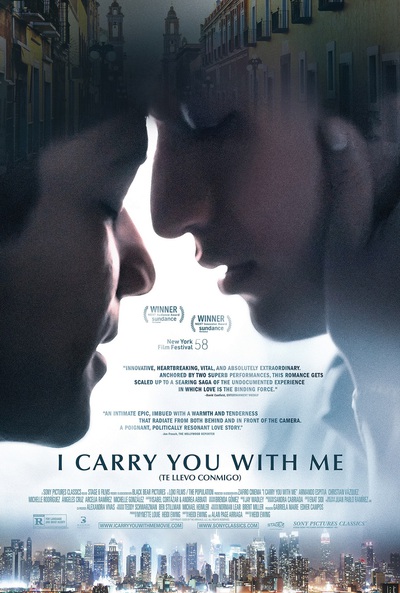

9: Hope beyond reason: Time and I Carry You With Me ↯

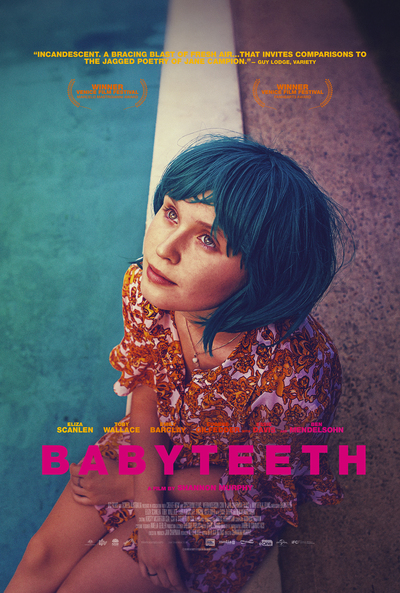

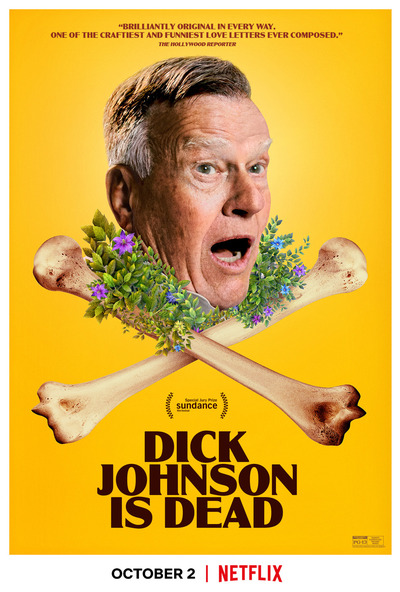

8: Own the inevitable: Babyteeth and Dick Johnson Is Dead ↯

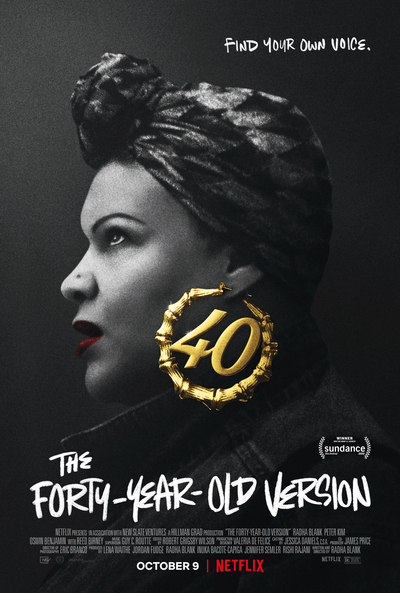

7: Define your opposition: One Night In Miami and The Forty-Year-Old Version ↯

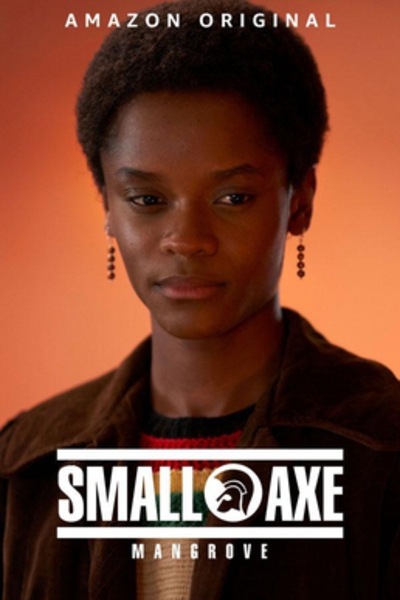

6: Recognize oppressive structures: The Assistant and Mangrove ↯

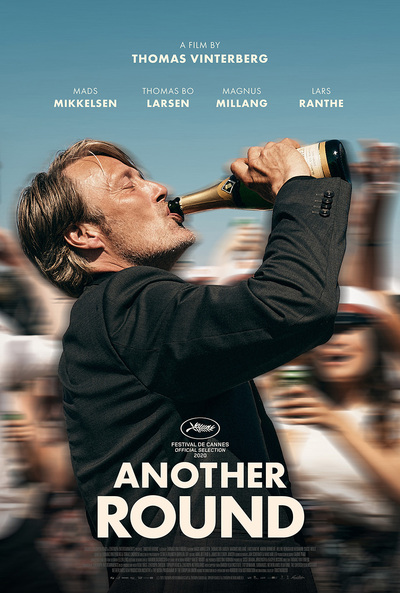

5: Break calcified routines: Palm Springs and Another Round ↯

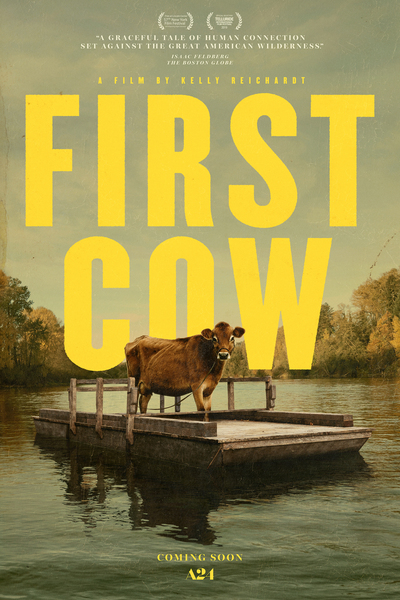

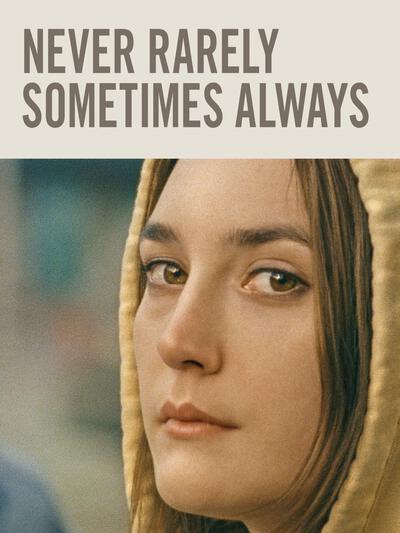

4: Rely on one another: First Cow and Never Rarely Sometimes Always ↯

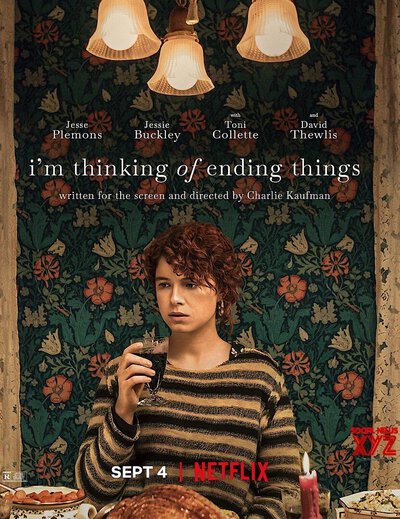

3: Depend without demanding: Shithouse and I’m Thinking Of Ending Things ↯

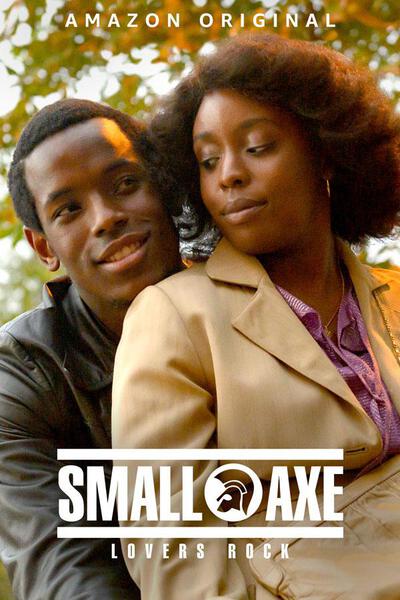

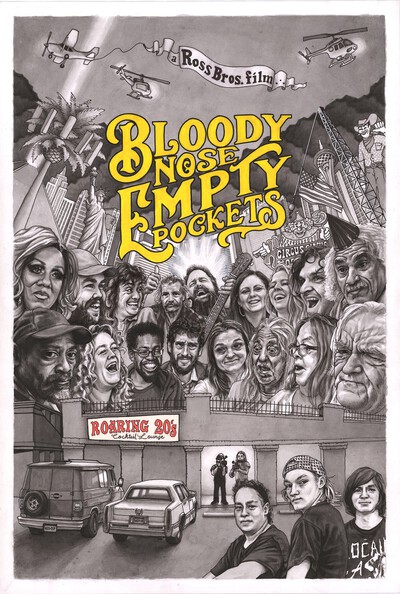

2: Find beauty in the motion blur: Lovers Rock and Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets ↯

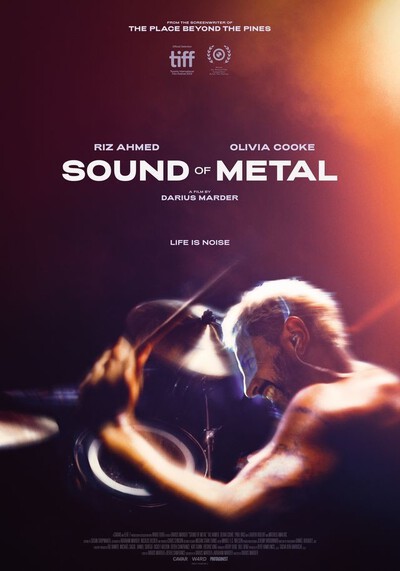

1: Find meaning in the stillness: Sound of Metal and Nomadland ↯

10. Cultivate curiosity: The Vast Of Night and Soul

My shelter-in-place period began with a slew of cancelled flights3, and the weeks that followed carried a genuine sense of loss. So much of my identity had been defined by superficial newness: new destinations, new career achievements, new experiences to add to my collection. In a world with fixed surroundings, what was left for me to be?

It took a little over a month for me to leave my apartment. When I finally did, I felt like I’d landed on an alien planet—spacesuit very much included. My daily commute had fostered the delusion that I knew my city deeply, but when I deviated from the tramlines it was clear I’d barely scratched the surface. There were parks I’d never seen before, thoroughfares I’d never walked, entire neighborhoods I couldn’t have named if they were circled on a map. Every new run became a personal expedition: What was beyond that hill up there? How did those two spots connect? What if you turned left instead of right? Being awestruck by beauty was a near-daily occurrence, and I’m not just talking about wildlife or panoramic views. An intersection at dusk could be a jaw-dropping revelation. A new angle of approach could feel unspeakably profound.

The Vast Of Night is an ode to that pervasive sense of wonder; the truth that tiny revelations could be hiding in plain sight. Even—especially—in those places where nothing seems to happen. A cloistered, quiet town with a gee-aw-shucks aesthetic. An evening radio program without a soul who’s calling in. A house that hasn’t seen a visitor in ages; a woman sitting there in silence, waiting for you to speak. With age we might grow numb to it, but in youth we knew the stakes. Curiosity is a muscle and it takes will to exercise it. Many will spend a lifetime looking forward, none the wiser. But ask the right question, tune to the right frequency, lift your eyes skyward, and you just might catch a glimpse.

The Vast Of Night is an ode to that pervasive sense of wonder; the truth that tiny revelations could be hiding in plain sight. Even—especially—in those places where nothing seems to happen. A cloistered, quiet town with a gee-aw-shucks aesthetic. An evening radio program without a soul who’s calling in. A house that hasn’t seen a visitor in ages; a woman sitting there in silence, waiting for you to speak. With age we might grow numb to it, but in youth we knew the stakes. Curiosity is a muscle and it takes will to exercise it. Many will spend a lifetime looking forward, none the wiser. But ask the right question, tune to the right frequency, lift your eyes skyward, and you just might catch a glimpse.

Incuriosity doesn’t always look like passivity; sometimes it looks like striving. Soul’s Joe Gardner isn’t lacking in motivation. Far from it. He knows what he wants, knows how to get it, and even knows how to make it transcendent: those moments on a piano bench when the world swirls to the periphery. His problem isn’t a failure to aim higher; it’s limiting the scope of his gaze. If being “swept up in the music” is the sole jurisdiction the stage, or “discovery” restricted to a distant, dim-lit runway, then it’s a fragile source of meaning, prone to wild fluctuations. His joy will always be beholden to his striving. A good steward of wonder ought to keep their portfolio diverse. Luckily, there is no shortage of options.

Incuriosity doesn’t always look like passivity; sometimes it looks like striving. Soul’s Joe Gardner isn’t lacking in motivation. Far from it. He knows what he wants, knows how to get it, and even knows how to make it transcendent: those moments on a piano bench when the world swirls to the periphery. His problem isn’t a failure to aim higher; it’s limiting the scope of his gaze. If being “swept up in the music” is the sole jurisdiction the stage, or “discovery” restricted to a distant, dim-lit runway, then it’s a fragile source of meaning, prone to wild fluctuations. His joy will always be beholden to his striving. A good steward of wonder ought to keep their portfolio diverse. Luckily, there is no shortage of options.

9. Hope beyond reason: Time and I Carry You With Me

Pragmatism and optimism are useful contradictions. I certainly felt extremes of each depending on the day. Hope without a center could cavern into recklessness. Reason without levity could harden to despair. “It’s no big deal.” “It will last forever.” “It doesn’t matter.” “It’s all that matters.”

Growing up in the church, there’s a phrase I’d hear recycled: “Live like it depends on you, pray like it depends on God.” It’s broad enough to mean just about anything, and has been abused enough to prove it. But it speaks to a very real tension, one which this year proved overwhelming. I’m talking about the struggle to do our due diligence without crumbling under pressure; to retain an optimistic spirit without losing our sense of ground. The need for a hope which doesn’t undermine reason, but rather augments it, lifts it up.

When we meet Sibil Fox Richardson in Time, she has reason to be discouraged. Her husband is serving a potentially life sentence for a confessed (nonviolent) crime. Despite a mountain of legal fees and failed appeals, things have shown little sign of changing. When her children were born, Rob was behind bars; when they graduated high school, he was still behind bars. She acknowledges her situation, and works to rise above it: working multiple jobs, taking public speaking gigs, partnering with criminal justice advocacy groups. But pragmatism alone can’t withstand 21 years of separation. It’s her love that keeps the family together, and hope that keeps them moving forward: phone calls, visits, filmed Big Moments, even a life-sized cardboard cutout. Her hope for her husband’s freedom is far more than some empty coping mechanism. It’s a vital attribute on which his freedom will depend.

When we meet Sibil Fox Richardson in Time, she has reason to be discouraged. Her husband is serving a potentially life sentence for a confessed (nonviolent) crime. Despite a mountain of legal fees and failed appeals, things have shown little sign of changing. When her children were born, Rob was behind bars; when they graduated high school, he was still behind bars. She acknowledges her situation, and works to rise above it: working multiple jobs, taking public speaking gigs, partnering with criminal justice advocacy groups. But pragmatism alone can’t withstand 21 years of separation. It’s her love that keeps the family together, and hope that keeps them moving forward: phone calls, visits, filmed Big Moments, even a life-sized cardboard cutout. Her hope for her husband’s freedom is far more than some empty coping mechanism. It’s a vital attribute on which his freedom will depend.

I Carry You With Me is also about a hope that insists upon itself, regardless of the roadblock. Iván and Gerardo fall in love despite families who won’t accept them. Hope then propels them to seek opportunity in a place that won’t receive them. And when the city threatens to crush them—when poverty is more than they can stand—hope encourages them to continue pressing on. Despite decades defined by forced separations between lover and lover, then father and son, they carve out a piece of the American dream…one that is endlessly threatened by the country that brands it. Still, they endure. They demand a better life. And they bridge all borders in the process: hometown and home, acquaintance and family, documentary and fiction.

I Carry You With Me is also about a hope that insists upon itself, regardless of the roadblock. Iván and Gerardo fall in love despite families who won’t accept them. Hope then propels them to seek opportunity in a place that won’t receive them. And when the city threatens to crush them—when poverty is more than they can stand—hope encourages them to continue pressing on. Despite decades defined by forced separations between lover and lover, then father and son, they carve out a piece of the American dream…one that is endlessly threatened by the country that brands it. Still, they endure. They demand a better life. And they bridge all borders in the process: hometown and home, acquaintance and family, documentary and fiction.

8. Own the inevitable: Babyteeth and Dick Johnson Is Dead

It was a year tailor-made for my personal anxieties. For the asthmatic, a deadly airborne virus with a hefty side of wildfire. For the hypochondriac, an imperative to self-diagnose based on the haziest of symptoms. For the neurotic overthinker prone to stress-induced panic: a closure of gyms, a reliance on takeout, weeks glued to a couch under a stockpile of whisky.

Prevention has its limits, even in a good year. You can only avoid stressors up to a point—one which “global pandemic” handily clears. The real trick of living with anxiety is learning to steer into the skid. You recognize the wave of dread washing over you, and choose to ride in its direction rather than feel trapped under its weight. The outcome may be similar, but you flow through it differently.

When confronted with trauma, most characters in Babyteeth run in the opposite direction. Milla’s father (a psychiatrist) keeps his feelings bottled up, and keeps his wife’s suspended in a dull prescription haze. Moses hides his loss behind a veil of liberation: he is free to do whatever he wishes, provided it destroys him. Free to run at breakneck speeds towards an oncoming train; free to break into Milla’s parents’ house (but not his family home). Only Milla, 16 years old and facing terminal cancer, seems willing to look the monster in the eye. Like American Honey’s rowdy van crew, swerving towards salvation, her methods may seem ill-advised, immature, or careless. But she’s closer to the truth than all the adults who try to numb it out.

When confronted with trauma, most characters in Babyteeth run in the opposite direction. Milla’s father (a psychiatrist) keeps his feelings bottled up, and keeps his wife’s suspended in a dull prescription haze. Moses hides his loss behind a veil of liberation: he is free to do whatever he wishes, provided it destroys him. Free to run at breakneck speeds towards an oncoming train; free to break into Milla’s parents’ house (but not his family home). Only Milla, 16 years old and facing terminal cancer, seems willing to look the monster in the eye. Like American Honey’s rowdy van crew, swerving towards salvation, her methods may seem ill-advised, immature, or careless. But she’s closer to the truth than all the adults who try to numb it out.

Kirsten Johnson doesn’t want to flee from it. In the title alone, she puts her cards on the table: Dick Johnson Is Dead. The eponymous Dick is losing his memory, and one day he will die. There’s no fixing it or slowing it; there’s no equivalent vaccine. The best the father/daughter duo can do is serve as creative consultants. And so, Dick begins play-acting his inevitable future, even as the spectre of it creeps into his present. He’s knocked out by a wooden plank; he tumbles down the stairs; a window AC unit falls directly on his head. He attends his own funeral, bawls through the eulogy, and dances with his departed wife in a bedazzled, cotton candy heaven. It may sound depressing, but it genuinely is not: By fictionalizing his own mortality, he’s somehow made it lovely. There are tragic possibilities beyond any of our control. Still, with a buoyancy of spirit and bit of trick photography, we can make the choice to elevate the narrative.

Kirsten Johnson doesn’t want to flee from it. In the title alone, she puts her cards on the table: Dick Johnson Is Dead. The eponymous Dick is losing his memory, and one day he will die. There’s no fixing it or slowing it; there’s no equivalent vaccine. The best the father/daughter duo can do is serve as creative consultants. And so, Dick begins play-acting his inevitable future, even as the spectre of it creeps into his present. He’s knocked out by a wooden plank; he tumbles down the stairs; a window AC unit falls directly on his head. He attends his own funeral, bawls through the eulogy, and dances with his departed wife in a bedazzled, cotton candy heaven. It may sound depressing, but it genuinely is not: By fictionalizing his own mortality, he’s somehow made it lovely. There are tragic possibilities beyond any of our control. Still, with a buoyancy of spirit and bit of trick photography, we can make the choice to elevate the narrative.

7. Define your opposition: One Night In Miami and The Forty-Year-Old Version

“Who are you, really?” It was a question that haunted us on multiple levels. Individual: What gets you out of bed in the morning? Communal: What lengths will you go to protect your neighbor? Societal: Which definition of hope do you choose to believe in, and whom will you trample to get it?

Amid these existential questions came the murder of George Floyd, and all of the above lines were blurred beyond distinction. Frantic corporate lip service rang as treacly and insufficient; law-and-order finger wagging revealed as evil and obtuse. There was overwhelming anger and no tidy place to hide it, no checkbox on a paper ballot, no symbolic resolution. It left no room for people-pleasing, waffling, “moderation”—those staples of white liberalism by which nothing seems to change. The stuff that change is made of was right outside the window, marching in the city square, demanding a response. Who are you? Oh, really? So what exactly will you do?

To the four main interlocutors of One Night In Miami, the answer’s not as obvious as it appears on first inspection. In broad strokes, of course, they all agree: the goal is to combat a racist system. But the devil is in the details. To Cassius Clay, the answer lies in rising above the system: excellence and fearless self-identification. To Jim Brown and Sam Cooke, it’s about cleverly exploiting the system from within: slowly amassing power and inspiring others to do the same, till eventually it tips toward an equitable direction. If that maneuver demands a sacrifice, surely the ends justify the means? But to Malcolm X, no nudge can salvage a country that’s rotten to the core: The only way to fix it is to burn the system down. A half century later, as history tragically reverberates, it’s hard to shake the prescience of his words.

To the four main interlocutors of One Night In Miami, the answer’s not as obvious as it appears on first inspection. In broad strokes, of course, they all agree: the goal is to combat a racist system. But the devil is in the details. To Cassius Clay, the answer lies in rising above the system: excellence and fearless self-identification. To Jim Brown and Sam Cooke, it’s about cleverly exploiting the system from within: slowly amassing power and inspiring others to do the same, till eventually it tips toward an equitable direction. If that maneuver demands a sacrifice, surely the ends justify the means? But to Malcolm X, no nudge can salvage a country that’s rotten to the core: The only way to fix it is to burn the system down. A half century later, as history tragically reverberates, it’s hard to shake the prescience of his words.

Radha Blank is living in that “half century later”, and her dilemma in The Forty-Year-Old Version is eerily similar to Cooke’s. Overt racism may have been traded in for smiling condescension, but the resulting power structures are more or less the same. In order to succeed as a playwright, she finds herself beholden to white sensibilities: white producers with a hunger for “poverty porn,” white directors on the marquee because “all the others were taken,” white audiences who pay to be “challenged” precisely to a Hamilton-sized point. She’s a flesh and blood artist in a feel-good PR world, one that claims to crave diversity while dictating the contours it must take. And so she finds herself trapped between two competing types of silence. How can authenticity inspire if it means toiling in obscurity? Then again, what’s the value of a platform if it’s in someone else’s voice? With no good option offered to her, she creates one of her own.

Radha Blank is living in that “half century later”, and her dilemma in The Forty-Year-Old Version is eerily similar to Cooke’s. Overt racism may have been traded in for smiling condescension, but the resulting power structures are more or less the same. In order to succeed as a playwright, she finds herself beholden to white sensibilities: white producers with a hunger for “poverty porn,” white directors on the marquee because “all the others were taken,” white audiences who pay to be “challenged” precisely to a Hamilton-sized point. She’s a flesh and blood artist in a feel-good PR world, one that claims to crave diversity while dictating the contours it must take. And so she finds herself trapped between two competing types of silence. How can authenticity inspire if it means toiling in obscurity? Then again, what’s the value of a platform if it’s in someone else’s voice? With no good option offered to her, she creates one of her own.

6. Recognize oppressive structures: The Assistant and Mangrove

Not all problems can be solved on an individual level. Systems are slow to change and reject attempts to self-critique. Politicians insist that everything is fine till the moment it behooves them to stop. Market forces surge to protect market interests; officers incite violence to secure their own necessity. And while Malcolm X would surely argue that “recognition” is insufficient, it’s a bare minimum that’s still depressingly difficult to clear. It’s tough to fight collective battles when the villain can’t be named.

The Assistant’s nameless villain is easy to recognize—the real life man he’s sketched from as well as his cookie-cutter imitations. But while Jane’s boss is surely a monster, he’s not presented as the film’s primary threat. The true source of horror comes from the people in her orbit: the monochromatic pack of yes-men who excuse him, insulate him, turn a blind eye with a smirk. While he remains lurking in the background, they are brought starkly into focus. It’s the coworkers who dictate her servile apology while looming just behind her; the dead-eyed HR rep who wields “listening” like a weapon; the conference room attendee who gives a look that makes simple pleasures feel like stealing. As we follow Jane through a single, hellish workday, we don’t need to hear the abuser directly to understand how he exists. If we tune to different frequencies, we can make it out clearly: the hum of abuse in the system’s design.

The Assistant’s nameless villain is easy to recognize—the real life man he’s sketched from as well as his cookie-cutter imitations. But while Jane’s boss is surely a monster, he’s not presented as the film’s primary threat. The true source of horror comes from the people in her orbit: the monochromatic pack of yes-men who excuse him, insulate him, turn a blind eye with a smirk. While he remains lurking in the background, they are brought starkly into focus. It’s the coworkers who dictate her servile apology while looming just behind her; the dead-eyed HR rep who wields “listening” like a weapon; the conference room attendee who gives a look that makes simple pleasures feel like stealing. As we follow Jane through a single, hellish workday, we don’t need to hear the abuser directly to understand how he exists. If we tune to different frequencies, we can make it out clearly: the hum of abuse in the system’s design.

If a collective pact of silence can prop up an abusive system, a collective shout might have a fighting chance at knocking it down. The police who raid The Mangrove are powerful and shameless: they topple tables, smash bottles, and accost its patrons with impunity. And in August 1970, after a long string of abuses, the Afro-Caribbean community of Notting Hill chooses to fight back. They march. They riot. They are arrested and detained by forces which show no interest in their testimony. But through a grueling courtroom battle, they stand united in their witness. They refuse to fold under pressure; they insist on naming the monster. And though a half century later we still hear the echo of abuses, we also hear the voices of those who dared to call it out: bold, unwavering, defiant.

If a collective pact of silence can prop up an abusive system, a collective shout might have a fighting chance at knocking it down. The police who raid The Mangrove are powerful and shameless: they topple tables, smash bottles, and accost its patrons with impunity. And in August 1970, after a long string of abuses, the Afro-Caribbean community of Notting Hill chooses to fight back. They march. They riot. They are arrested and detained by forces which show no interest in their testimony. But through a grueling courtroom battle, they stand united in their witness. They refuse to fold under pressure; they insist on naming the monster. And though a half century later we still hear the echo of abuses, we also hear the voices of those who dared to call it out: bold, unwavering, defiant.

5. Break calcified routines: Palm Springs and Another Round

Among the many vices this year put under a microscope, perhaps the most fickle was complacency.

I call it fickle because it’s a chameleon of an issue, and one which we Type A personalities are apt to misdiagnose. In the early days of quarantine, I mistook it for a lack of productivity—weekend Netflix benders, quadruple-snoozed alarms. And so, true to form, I overcompensated wildly. I would write every morning, run every evening, and fill every waking gap with devotion to my work. With healthier habits and an aggressive creative output, surely I could turn the ship around!

Except it turns out a default state of “output” is no less numbing than the others. Autopilot inevitably finds a way of creeping in: postponed conversations, friendships left untended, cultivated stressors based on unexamined rationale. I must do X, or else…what, exactly? The answer hardly matters. Given enough time, the routine justifies its own existence.

The temptation to revert into habit was hardly new to 2020. But devoid of any prime mover outside the confines of my living room, the absurdity of that struggle felt even more pronounced.

“Absurdity” is the operative word for the protagonists of Palm Springs. Caught in a loop at a destination wedding, they’ve found themselves on the inside of a Camus hypothetical. Social niceties dissolve; distractions prove impermanent; all goal-oriented striving seems meaningless from the jump. They’ve come at it from a thousand angles, and still the stone is rolling. What’s the point in trying to shake things loose? Maybe there’s really nothing left to do but lay back in a pool floatie (with a dozen Akuparas) and let life just happen to them, ad nauseam absurdum. Or is there a reason to push back against their daily, mundane comforts? “Less mundane,” Nyles considers, “That’s a super low bar. That’s a great place to start.”

“Absurdity” is the operative word for the protagonists of Palm Springs. Caught in a loop at a destination wedding, they’ve found themselves on the inside of a Camus hypothetical. Social niceties dissolve; distractions prove impermanent; all goal-oriented striving seems meaningless from the jump. They’ve come at it from a thousand angles, and still the stone is rolling. What’s the point in trying to shake things loose? Maybe there’s really nothing left to do but lay back in a pool floatie (with a dozen Akuparas) and let life just happen to them, ad nauseam absurdum. Or is there a reason to push back against their daily, mundane comforts? “Less mundane,” Nyles considers, “That’s a super low bar. That’s a great place to start.”

The characters in Another Round are also seeking an escape from the mundane, though their problem isn’t repetition so much an anhedonic rut. Students who don’t give a damn; rote and loveless marriages. That gnawing sense that life has nothing new to offer. And so they do what you or I might when facing a mid-life crisis: They pour themselves a drink. Except they aren’t using alcohol to numb the world, as most films would depict it. No, they’re drinking with the intent of more fully experiencing the world; taking a sledgehammer to their inhibitions to see what’s on the other side. What follows is a sort of guerilla academic study…or at least that’s the excuse. Some of their discoveries are absolutely hilarious. Others are extraordinarily depressing. Even an unchecked hunt for novelty can become its own calcified routine. But there’s a profane wisdom at the heart of their ill-advised experiment, and a vicarious thrill in watching the demolition.

The characters in Another Round are also seeking an escape from the mundane, though their problem isn’t repetition so much an anhedonic rut. Students who don’t give a damn; rote and loveless marriages. That gnawing sense that life has nothing new to offer. And so they do what you or I might when facing a mid-life crisis: They pour themselves a drink. Except they aren’t using alcohol to numb the world, as most films would depict it. No, they’re drinking with the intent of more fully experiencing the world; taking a sledgehammer to their inhibitions to see what’s on the other side. What follows is a sort of guerilla academic study…or at least that’s the excuse. Some of their discoveries are absolutely hilarious. Others are extraordinarily depressing. Even an unchecked hunt for novelty can become its own calcified routine. But there’s a profane wisdom at the heart of their ill-advised experiment, and a vicarious thrill in watching the demolition.

4. Rely on one another: First Cow and Never Rarely Sometimes Always

When the world is suddenly held at an impossible remove, the people in your orbit become more vital than ever. It’s true in the relational sense—I cannot fathom surviving the last 9+ months without a loving partner to keep me grounded. But it’s also true more broadly, encompassing the friends and family you chat with on Zoom, the neighbor who waves in the hallway, the local cooks who keep you fed regardless of the holiday. We are all irrevocably connected. 2020 was a year of being humbled, of learning to negotiate those connections. Of needing to rely on one another and be made reliable in kind.

The untamed West of First Cow puts little stock in personal connection. In a time and place defined by dogmatic individualism—boundless expansion, the elusive promise of gold—you are only deemed as “valuable” as the service you provide. When they meet, King-Lu and Cookie have found themselves victims of that cold calculus, and they hope (like so many) to eventually tip the scales. But while their story functions neatly as an economic parable, its real beating heart lies in subtler exchanges. It’s the unassuming manner in which Cookie sweeps the floor; the way King-Lu voices an idea as if he could see it in the distance. It’s about the spirit of friendship, impervious to circumstance, which can transform the harshest raw materials into something like a home. Two people, side by side, keeping warm.

The untamed West of First Cow puts little stock in personal connection. In a time and place defined by dogmatic individualism—boundless expansion, the elusive promise of gold—you are only deemed as “valuable” as the service you provide. When they meet, King-Lu and Cookie have found themselves victims of that cold calculus, and they hope (like so many) to eventually tip the scales. But while their story functions neatly as an economic parable, its real beating heart lies in subtler exchanges. It’s the unassuming manner in which Cookie sweeps the floor; the way King-Lu voices an idea as if he could see it in the distance. It’s about the spirit of friendship, impervious to circumstance, which can transform the harshest raw materials into something like a home. Two people, side by side, keeping warm.

When I think about the characters in Never Rarely Sometimes Always—bundled up in jackets, half sleeping on the train—I’m reminded of that haunting bookend image. It’s a long way from 19th century Oregon to present New York City, but the same cruel calculation remains an all-consuming force. We still accommodate or discard based on a reductive sense of value. Autumn, the film’s protagonist, is among the too-easily discarded. 17 years old, pregnant, and more or less broke, she’s perpetually been treated like a nuisance. And she seems to have internalized that message—prone to lengthy bouts of silence, turning inward as an instinct. So in those moments when a bureaucratic hurdle would threaten her resolve, it’s her older cousin Skylar who needs to keep her pressing onward. Which isn’t to imply that Skylar’s particularly happy to be needed. What moves me about their friendship is that it isn’t sentimental. Skylar isn’t a shoulder to cry on or a comforting distraction. Rather, she’s an advocate, insisting on Autumn’s agency even to the point of annoyance. She can’t dictate Autumn’s choice, but she can nudge her towards some clarifying questions—and to a room where she’ll be granted space to answer.

When I think about the characters in Never Rarely Sometimes Always—bundled up in jackets, half sleeping on the train—I’m reminded of that haunting bookend image. It’s a long way from 19th century Oregon to present New York City, but the same cruel calculation remains an all-consuming force. We still accommodate or discard based on a reductive sense of value. Autumn, the film’s protagonist, is among the too-easily discarded. 17 years old, pregnant, and more or less broke, she’s perpetually been treated like a nuisance. And she seems to have internalized that message—prone to lengthy bouts of silence, turning inward as an instinct. So in those moments when a bureaucratic hurdle would threaten her resolve, it’s her older cousin Skylar who needs to keep her pressing onward. Which isn’t to imply that Skylar’s particularly happy to be needed. What moves me about their friendship is that it isn’t sentimental. Skylar isn’t a shoulder to cry on or a comforting distraction. Rather, she’s an advocate, insisting on Autumn’s agency even to the point of annoyance. She can’t dictate Autumn’s choice, but she can nudge her towards some clarifying questions—and to a room where she’ll be granted space to answer.

3. Depend without demanding: Shithouse and I’m Thinking Of Ending Things

Any relationship worth preserving calls for symmetry and restraint. In a year when our connectedness proved immeasurably vital, it also proved a frequent (sometimes deadly) source of strain. Marriages crumbled; disinformation ran unchecked; peer pressure drove behavior to the point of reckless abandon. No one is an island. And yet, some parts need to stand alone.

I grappled with this on a personal level. My “level-headed” instinct led to inwardness, opacity; my desire to be the hero made me a walking ball of stress. I have never been so thoroughly stuck inside my skull. At the same time, I’ve never felt a greater temptation to crowdsource my anxieties: to heap my burdens onto friends and strangers in the name of vulnerability, or better, to lose myself entirely in a sea of communal cynicism. It’s a delicate balance. Wall off too completely and we become governed by neuroses; rely on others too aggressively and we lose our sense of self. How do we split the difference?

Maggie thinks the point of college is to discover who you are. Alex adds a corollary: it’s to support each other in the process. That tension between independence and codependence, personal identity and group identification, is the emotional crux of Shithouse. It also happens to be the emotional crux of growing up. After 18 years of life primarily steered by someone else, you suddenly find yourself miles from home, alone behind the wheel. What do you do? Move too far in either direction and it loops back on itself. Camp up in your dorm room, walled off from the universe, and you’ll postpone any chance at self-discovery. Push your social life to the breaking point with an endless string of parties, and you’ll never feel more thoroughly alone. Meet someone who sharpens you, engage in “life-changing” conversation, and in the glow of wine and streetlamps you’ll catch a glimpse of who you are. Irreparably blow it the following morning as want curdles to obsession, and you’ll get a clearer picture of the mess that’s left to fix. A girl is not a savior; a crowd is not a family; loneliness is not a badge of philosophic rigor. Through a lifetime of trying and failing and wildly overcompensating, a real self will come into view. Even still, you’ll always look back fondly on those nights of aimless searching. On that time when all of “you” hung in the balance.

Maggie thinks the point of college is to discover who you are. Alex adds a corollary: it’s to support each other in the process. That tension between independence and codependence, personal identity and group identification, is the emotional crux of Shithouse. It also happens to be the emotional crux of growing up. After 18 years of life primarily steered by someone else, you suddenly find yourself miles from home, alone behind the wheel. What do you do? Move too far in either direction and it loops back on itself. Camp up in your dorm room, walled off from the universe, and you’ll postpone any chance at self-discovery. Push your social life to the breaking point with an endless string of parties, and you’ll never feel more thoroughly alone. Meet someone who sharpens you, engage in “life-changing” conversation, and in the glow of wine and streetlamps you’ll catch a glimpse of who you are. Irreparably blow it the following morning as want curdles to obsession, and you’ll get a clearer picture of the mess that’s left to fix. A girl is not a savior; a crowd is not a family; loneliness is not a badge of philosophic rigor. Through a lifetime of trying and failing and wildly overcompensating, a real self will come into view. Even still, you’ll always look back fondly on those nights of aimless searching. On that time when all of “you” hung in the balance.

Want curdles to obsession. There’s little I can say about I’m Thinking Of Ending Things without spoiling the experience, but that hard truth Alex learns is at its root. We are so desperate to be loved, recognized, included—and desperation can grow toxic, regardless of intent. A chilly echo chamber, an infinite regress. Whether seeking validation in a high paying career or a top shelf degree, a stirring creative project or a scorched earth criticism. Whether marching in support of some bloated sense of “Great”-ness, or sneering from the sidelines, lobbing dry, ironic stones. “Whether you have a wife or just a wife-shaped loneliness waiting for you.” We need other people—real ones—to keep that need from caving in on itself; to challenge us, defy our basest expectations. Alex and Maggie’s theories are both right, in a sense. A healthy independence requires some network of support: external voices reiterating our authentic selves to us.

Want curdles to obsession. There’s little I can say about I’m Thinking Of Ending Things without spoiling the experience, but that hard truth Alex learns is at its root. We are so desperate to be loved, recognized, included—and desperation can grow toxic, regardless of intent. A chilly echo chamber, an infinite regress. Whether seeking validation in a high paying career or a top shelf degree, a stirring creative project or a scorched earth criticism. Whether marching in support of some bloated sense of “Great”-ness, or sneering from the sidelines, lobbing dry, ironic stones. “Whether you have a wife or just a wife-shaped loneliness waiting for you.” We need other people—real ones—to keep that need from caving in on itself; to challenge us, defy our basest expectations. Alex and Maggie’s theories are both right, in a sense. A healthy independence requires some network of support: external voices reiterating our authentic selves to us.

2. Find beauty in the motion blur: Lovers Rock and Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets

“I miss the world.” It’s a phrase that I couldn’t shake this year, and it tinted every movie. There were always two stories: the thing unfolding on the screen, and the fact of its creation. Behind every plot machination or emotional journey hid a broader human narrative about shared, collective space. A shimmering Manhattan skyline became a vehicle for nostalgia. An establishing shot of a bustling café became a revelation in itself—this was something we used to do together. A handshake became a Chekhov’s gun; a sneeze an all-out nightmare. Airplanes seemed fantastical, apocalyptic wastelands too familiar, and extravagant action set pieces turned vicarious and meta: “They took a camera crew where and blew up what?!”

You grow so accustomed to motion it’s easy to forget there’s any other setting. In February of 2020, I might have complained about a thousand things which I now see as distant, lovely memories. A jam-packed bus on a rainy morning commute with neighbor sardined against neighbor. A gaggle of club-goers screaming on my block every Thursday through Saturday evening. How you sometimes had to wait a goddamn hour to get a table at Mikkeller. How even then you’d have to shout to get a word in.

Lovers Rock might be the purest expression of precisely what I miss. It’s an act of surrender, of intentional forgetting. People gathering in a crowded room from all possible stations, setting down their burdens to simply be alive, together. A voice melding into a choir. A bass you could feel in your chest. An outside world which doesn’t fade out entirely—Babylon sirens blending into the upstroke. It’s that feeling of letting go, of having permission to abandon, of forfeiting the need to make any conscious choice. It’s the dinner that balloons into four hours of stories, the joke that isn’t funny which leaves everyone in tears, the audience shouting lyrics till they can barely hear the band. It’s the stuff that never fits inside the confines of a Zoom call, no matter how creative our attempt. It’s the magic of kinetic energy: bodies packed into a tiny space, unscheduled, sharing heat.

Lovers Rock might be the purest expression of precisely what I miss. It’s an act of surrender, of intentional forgetting. People gathering in a crowded room from all possible stations, setting down their burdens to simply be alive, together. A voice melding into a choir. A bass you could feel in your chest. An outside world which doesn’t fade out entirely—Babylon sirens blending into the upstroke. It’s that feeling of letting go, of having permission to abandon, of forfeiting the need to make any conscious choice. It’s the dinner that balloons into four hours of stories, the joke that isn’t funny which leaves everyone in tears, the audience shouting lyrics till they can barely hear the band. It’s the stuff that never fits inside the confines of a Zoom call, no matter how creative our attempt. It’s the magic of kinetic energy: bodies packed into a tiny space, unscheduled, sharing heat.

To the barflies who populate Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, motion blur is more than a temporary reprieve. It’s the fundamental texture of living. You’ve met them, I’m sure—the guy who slurs through his last three marriages on an endless flight delay, the woman who roars with gravely laughter before you’ve even hit the punchline. But have you ever really seen them? Beyond the faux philosophic discussions and liver defying habits, lies an all-too-human yearning to unburden. An eagerness to be made vulnerable, to know and be made known, to thoroughly dissolve into a crowd. Like the characters in Another Round, they elicit an empathy that runs deeper than any judgment. Perched behind the counter for their Roaring last hurrah, it’s easy to get swept up in the afterglow.

To the barflies who populate Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, motion blur is more than a temporary reprieve. It’s the fundamental texture of living. You’ve met them, I’m sure—the guy who slurs through his last three marriages on an endless flight delay, the woman who roars with gravely laughter before you’ve even hit the punchline. But have you ever really seen them? Beyond the faux philosophic discussions and liver defying habits, lies an all-too-human yearning to unburden. An eagerness to be made vulnerable, to know and be made known, to thoroughly dissolve into a crowd. Like the characters in Another Round, they elicit an empathy that runs deeper than any judgment. Perched behind the counter for their Roaring last hurrah, it’s easy to get swept up in the afterglow.

1. Find meaning in the stillness: Sound of Metal and Nomadland

We lost that sense of motion. And it’s appropriate to grieve it as a loss, charges of “first world problem” (however accurate) be damned. Even now, almost a full year into this thing, I struggle to find a substitute for that overcrowded, sweaty bus. I wake up and run to the rhythm of a chipmunk-speed novel; I fall asleep to the white noise of political analyses and improv. I have somehow found a way to make Solitaire a speed race. I fill my life with all manner of pre-programmed distraction, yet it’s impossible to mistake them for the real, organic thing. I miss having an unpredictable world to get lost in.

In grieving it, though, I’ve learned a truth about myself: the degree to which I couldn’t stand the stillness. It wasn’t as if I were merely bored in those first few weeks of March; I was restless, craving some primal release. I was addicted to the bustle, to the myth of forward motion. Like the daily second espresso I’m sipping as I write this, it had always seemed a harmless, manageable vice. But when the machine went on the fritz, I became a wreck.

When grappling with panic attacks in my mid-to-late 20’s, I occasionally dabbled in meditation. I say “dabbled” because, in truth, I never got further than the third or fourth “breathe out.” Lying flat on my back with my eyes screwed shut, focusing on nothing but existing—it felt like being held underwater, or staring directly at the sun. Every biological system rebelled: distract, distract, distract.

Could there be a more fitting complement to this year than Sound of Metal? Over the course of a single day, Ruben loses virtually everything that defines him: the vintage record player, the whir of his blender, the thrill of live performance, the whisper of “goodnight.” He’s lost his hearing, yes, but more importantly he’s lost the noise. If his former life as an addict was defined by a singular want, noise offered him the promise of plurality. A divided attention, a translucent swath of “focus,” a sludge of stimuli dense enough to dampen any urge. Dissolved into the chaos of a Friday night set, Ruben could be everywhere and nowhere. Now he can only be here: a place where stillness is the default, and listening a clear and conscious choice. All system rebel on that first early morning, alone with his coffee and his donut and his thoughts. But slowly he weans himself off of the chatter. He grieves his old life and learns to carve out a new one, discovering new gifts in its absence.

Could there be a more fitting complement to this year than Sound of Metal? Over the course of a single day, Ruben loses virtually everything that defines him: the vintage record player, the whir of his blender, the thrill of live performance, the whisper of “goodnight.” He’s lost his hearing, yes, but more importantly he’s lost the noise. If his former life as an addict was defined by a singular want, noise offered him the promise of plurality. A divided attention, a translucent swath of “focus,” a sludge of stimuli dense enough to dampen any urge. Dissolved into the chaos of a Friday night set, Ruben could be everywhere and nowhere. Now he can only be here: a place where stillness is the default, and listening a clear and conscious choice. All system rebel on that first early morning, alone with his coffee and his donut and his thoughts. But slowly he weans himself off of the chatter. He grieves his old life and learns to carve out a new one, discovering new gifts in its absence.

By the time we meet Fern on the road in Nomadland, she has already lost one life and fashioned herself a new one. Though in a literal sense, her story is flipped: Fern grieves the loss of stillness via therapeutic motion. With the death of her husband and the closure of her workplace, she no longer sees any reason to stay anchored. So she drives, and drives, and drives. Living in a van and working seasonal gigs, she is tethered to nowhere and no one. But what she’s seeking in an open road is the same as Ruben in his kitchen. Absolute solitude. A sufficiency of being. The ability to survive without the bustle. As she weaves from job to job through the American Midwest, it’s not always clear exactly where she’s headed. Some nights it seems like she’s fleeing from something; some nights it seems like she’s found it. There’s no perfect way to meditate, no ideal way to grieve. But in the experience of watching her, there’s no mistaking the directive: an urge to turn down the volume, soak in the landscape, embrace our private wilderness and be.

By the time we meet Fern on the road in Nomadland, she has already lost one life and fashioned herself a new one. Though in a literal sense, her story is flipped: Fern grieves the loss of stillness via therapeutic motion. With the death of her husband and the closure of her workplace, she no longer sees any reason to stay anchored. So she drives, and drives, and drives. Living in a van and working seasonal gigs, she is tethered to nowhere and no one. But what she’s seeking in an open road is the same as Ruben in his kitchen. Absolute solitude. A sufficiency of being. The ability to survive without the bustle. As she weaves from job to job through the American Midwest, it’s not always clear exactly where she’s headed. Some nights it seems like she’s fleeing from something; some nights it seems like she’s found it. There’s no perfect way to meditate, no ideal way to grieve. But in the experience of watching her, there’s no mistaking the directive: an urge to turn down the volume, soak in the landscape, embrace our private wilderness and be.

It’s been almost a full year since I cut the world cold turkey, and I still can’t say I’ve really kicked the habit. I’m still loathe to walk a room’s length without headphones; I still get stuck in manic fits of scrolling. But I’ve picked up a few tricks that I’d like to carry with me, in that (reasonably hopeful) future when the spinning will resume. Like this one: waking before sunrise, pulling the morning’s first espresso, taking in the skyline and standing absolutely still.

Closing Bits, Shameless Plugs

Hi there! If you made it this far, there’s a good chance you’ll enjoy some of my other writing. You can dig through previous years’ writeups, or find a bunch of individual film and book reviews. On a personal note, I undertook a hundred days of journaling towards the beginning of shelter-in-place. You can find that and other miscellaneous writings scattered throughout this site.

This marks my seventh consecutive year of film writeups, which is solely a labor of love. I am fortunate enough to need no financial support, and would reject any if offered. But there is one form of support I’m willing to grovel for: If you read and enjoyed this, I would love to hear from you! These things always get some level of traffic, but a faceless graph on my Google Analytics dash is a poor substitute for human connection. You can hit me up on Twitter, connect with me on Letterboxd, or just send a friendly email to stephen __at__ cs.stanford.edu.

-

The Assistant, caught a full month before quarantine.↩

-

If you’ve read any of my prior lists, you probably know the drill. While 20 films are listed here, and order is important, this is not meant to be taken as a straightforward Top 20. Some films were elevated by virtue of sharing a theme; some which I otherwise loved were excluded from the list. (A few casualties worth your attention: Blow the Man Down, Boys State, Da 5 Bloods, David Byrne’s American Utopia, The Invisible Man, Love and Monsters, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Mank, On the Rocks, Saint Frances). What it is, is a collection of thematic pairs ordered by how much the pairing moved me. My favorite films of the year are generally among the highest rated pairs, with the first film listed (A of “A and B”) typically my favorite of the two—though a few of these are virtual ties, including the number one slot. For a more traditional, flat list which will surely contradict this one, you can check out the podcast.↩

-

Mostly a handful of business trips (including one that very morning). More heartbreakingly, what would have been my third trip to the Cannes Film Festival—complete with a kickass AirBnB and an actual, no-more-begging-on-the-street-for-tickets press badge. Le sigh.↩