Things I wanted to see but hadn’t yet: Fences, Hacksaw Ridge, Krisha, Cameraperson, Birth of a Nation, Elle, Toni Erdmann, Edge of Seventeen

More ramblings: if one novel isn’t enough for you, you can also find my 2015 and 2014 top 10 lists.

Podcast: you can listen to a similar (but not identical) list I gave with my friends over at The Spoiler Warning.

Introduction: The Stories We Tell

Here’s a hot take for you: 2016 was a rough year. And while the reality of production schedules makes any causal link between the year in pain and the year in film highly questionable, the temptation is too strong to resist. So let’s ignore reality for a second, and pretend that every movie we saw this year was conceived of 15 minutes before we stepped in the theatre. What aches are they reacting to, and what is their response?

The first thing that I see is an overwhelming hunger for diversity. Not necessarily in the kinds of people who create films (though small improvements are being made here as well), but in the way their stories are being told. Soundtrack-heavy coming of age flicks, genre-defying documentaries, quietly contemplative tragedies, bombastic Golden Age throwbacks, dazzling exploitation flicks, and moody sci-fi pieces all have a place on this list. Cathartic outlets pointing in a thousand directions; a triumphant burst of things held too long inside.

I also see a strong rebuke to the politics of the day. Some of those are quite literal. I see heartfelt portraits of the poor and working class, white and black, rural and urban, struggling to find footing in a world that has left them behind. I see attempts to grapple with otherness and division: studies of race, gentrification, and the all-too-rare coming together of people. I see sexual awakenings; repressed teenagers, gay, lesbian, and straight, throwing labels aside and stepping fully into their skin. If there’s an abstract enemy, here, it’s cynicism and misanthropy. Some fight against it with full-bodied, sentimental joy: escapist fantasies, glorious tales of comeuppance and strength. Others try to break through it by sheer excess: parodies so pure they cease to be satire, love stories so cold they eventually feel warm. Still others try to sanctify it, flip it on its head: glowing odes to an inwardness that destroys all for art, for grief, for love. As if we’re trying to tell ourselves that this closed, jaded rut we’re stuck in isn’t due to a lack of meaning, but a protective response to its blinding, beautiful excess.

A true Top 10 list is too difficult to reign in, especially in a year with such beautiful excesses. So, in accordance with annual tradition, I’m going to shamelessly cheat every chance I get. Not only are the #10-#6 slots reserved for named awards with winners and runners up, but the #5-#1 awards are now for thematic pairs rather than individual films. Films that speak to similar aches, and complement each other in interesting ways. Flattening the list into a Top 15 + a handful of honorable mentions would be a reasonably solid reflection of my feelings, but where’s the fun in that? You only get one swing at a year like this. Put the pedal down and drive it like you stole it.

10-6: Awards: Winners and (Noteworthy) Runners Up

10. Dallas Buyers Club Award: Born to Be Blue

Every year I give this award to what I would call my least sexy favorite; the kind of film that will probably gather positive acclaim but zero buzz, that isn’t looking to rock the boat so much as propel it steadily forward. This is about recognizing the virtue of sturdy, unassuming filmmaking, and that label easily applies to Born to Be Blue; a soulful biopic about heroine-addicted jazz great Chet Baker. An ode to the all-consuming, life-threatening totality of art, the film could be thought of as Whiplash’s gentler older sibling. Artful without being cloying, melancholy without ever tumbling into masochism, I found it a quiet joy to watch. Ethan Hawke walks an impressive tightrope here. Baker is virtually Platonic in his role as tragic figure, and his self-destructive tendencies are laid out bare in Hawke. At the same time, he gives us just enough glimpses of genius to root for him without beatifying him, planting tiny seeds of doubt about our own urge to attribute labels. Reminiscent of its younger brother, the film ends with a provocative question: can moderation and free expression truly coexist, or must everything eventually burn? And is it really a tragedy if the victim sets himself on fire?

Every year I give this award to what I would call my least sexy favorite; the kind of film that will probably gather positive acclaim but zero buzz, that isn’t looking to rock the boat so much as propel it steadily forward. This is about recognizing the virtue of sturdy, unassuming filmmaking, and that label easily applies to Born to Be Blue; a soulful biopic about heroine-addicted jazz great Chet Baker. An ode to the all-consuming, life-threatening totality of art, the film could be thought of as Whiplash’s gentler older sibling. Artful without being cloying, melancholy without ever tumbling into masochism, I found it a quiet joy to watch. Ethan Hawke walks an impressive tightrope here. Baker is virtually Platonic in his role as tragic figure, and his self-destructive tendencies are laid out bare in Hawke. At the same time, he gives us just enough glimpses of genius to root for him without beatifying him, planting tiny seeds of doubt about our own urge to attribute labels. Reminiscent of its younger brother, the film ends with a provocative question: can moderation and free expression truly coexist, or must everything eventually burn? And is it really a tragedy if the victim sets himself on fire?

9. Annie Hall Award: Don’t Think Twice w/ Little Men

The Annie Hall Award is given to a talky flick, nearly always set in New York, which shines in its examination of human relationships. With Little Men, like former honoree Love is Strange, Ira Sachs continues to cement his tiny niche as poet laureate of the New York rent explosion. The film follows a budding friendship between two Brooklyn teens, the son of a shopkeeper and the son of her landlords. Rent increase and eviction hangs thick in the air, and we watch as the kids navigate the messy space laid out by their parents, trying to carve out a semblance of identity in the process. Sachs handles the melodrama with subtlety and wit: every performance is wonderfully small, and no one is cheapened or vilified.

This year’s winner, Don’t Think Twice, also has something to say about competing motives. Namely, the desire love instills in you for the other’s success, and the comfort of symmetry which made that love possible in the first place. Birbiglia introduces us to a tight-knit improv troupe, legends in the local comedy scene but barely getting by in life. The spectre of future success finally becomes a reality when a subset of the group are asked to audition for a barely-veiled riff on Saturday Night Live. As the story plays out, these competing impulses wear on the group: they want to root for each other’s victories, but those very victories only serve to alienate. I found the emotional beats remarkably true to life, but what I really loved here was how many tiny aspects of comedy Birbiglia gets right: the use of humor as coping mechanism against sadness, the spark of delight from finding something funny in the scorched earth where nothing funny can grow. I love that everything put to screen, from professional highs to personal lows, feels intimate and true. And the moments on the improv stage — so corny on the surface, so cringeworthy from the trailer — are pure magic.

This year’s winner, Don’t Think Twice, also has something to say about competing motives. Namely, the desire love instills in you for the other’s success, and the comfort of symmetry which made that love possible in the first place. Birbiglia introduces us to a tight-knit improv troupe, legends in the local comedy scene but barely getting by in life. The spectre of future success finally becomes a reality when a subset of the group are asked to audition for a barely-veiled riff on Saturday Night Live. As the story plays out, these competing impulses wear on the group: they want to root for each other’s victories, but those very victories only serve to alienate. I found the emotional beats remarkably true to life, but what I really loved here was how many tiny aspects of comedy Birbiglia gets right: the use of humor as coping mechanism against sadness, the spark of delight from finding something funny in the scorched earth where nothing funny can grow. I love that everything put to screen, from professional highs to personal lows, feels intimate and true. And the moments on the improv stage — so corny on the surface, so cringeworthy from the trailer — are pure magic.

8. Take The Premise And Run Award: The Lobster

As the name suggests, this one is given to a film which sets up a very specific premise and watches as its logical conclusions play out; a story whose elevator pitch alone contains multitudes. So let’s start with the elevator pitch for The Lobster. Imagine a world where everyone is forced, by law, to be in a relationship. Singles are sent to a resort with the express purpose of meeting other singles, and those that fail after a certain timeframe will be turned into the animal of their choice.

As the name suggests, this one is given to a film which sets up a very specific premise and watches as its logical conclusions play out; a story whose elevator pitch alone contains multitudes. So let’s start with the elevator pitch for The Lobster. Imagine a world where everyone is forced, by law, to be in a relationship. Singles are sent to a resort with the express purpose of meeting other singles, and those that fail after a certain timeframe will be turned into the animal of their choice.

Are you convinced to see it, or need I go on? It’s as if Charlie Kaufman and Wes Anderson had a misanthropic Greek baby. Or, in the world of the film, as if they bonded over a shared interest in hotel management and loneliness, graduated to a double room, argued like hell over the relative virtues of “heartfelt meaninglessness” and “quirky meaninglessness”, and were given a child to stop the shouting. Either way, I love the ornery bastard. It’s a wonderfully biting satire about relationships, and the constant pressure society imposes (or we impose upon ourselves?) to maintain them.

7. The Airplane Award: Hail Caesar with Eddie the Eagle and Zootopia

Typically I leave a slot on my list for blockbusters, for massively successful crowd-pleasers that also happened to be great. If 2016 had a diversity of strengths, though, it had one clear weakness: “great” blockbusters were virtually nonexistent. Nearly every highly anticipated adventure / thriller / tentpole left me wanting. So instead, I’ll pivot slightly and call this the Airplane Award, reserved for films that have the sort of broad, rewatchable appeal to make them perfect for a long plane ride. And I’d know, because all of these contenders were films I watched multiple times, on very long plane rides.

Eddie the Eagle might be the most pure dose of happiness I saw all year, a throwback to those uplifting sports flicks which were so ubiquitous in the 90’s. It’s goofy, tender, and kept me beaming from ear to ear. Zootopia (full review) also kept me beaming, and with its refreshingly frank take on otherness and the need to accept one another, it even managed to sneak in a few tears along the way. But Hail Caesar was the complete package: the sort of film that reveals more amazing layers with each successive rewatch. It’s puzzling to me, in a year where La La Land garnered ubiquitous acclaim for its retro Hollywood flare, that so many people seem to have forgotten this gem. Which isn’t to say that I didn’t love La La Land; only that I really really loved Hail Caesar. It has all the hallmarks of the best of the Coens’ oeuvre: delightfully funny, wickedly off-kilter, supremely confident and visually sumptuous. But what makes this a true gem, and possibly even an outlier in their work, is its earnest desire to inspire awe. We can laugh at Tatum’s sexually repressed sailor dance, or Johansson’s synchronized swim in a too-tight mermaid suit, but there’s something seriously impressive — even moving — about the spectacle. For a few moments in the dark of seat 22C, the world feels full of magic and possibility. The world after touchdown? Would that it were so simple.

Eddie the Eagle might be the most pure dose of happiness I saw all year, a throwback to those uplifting sports flicks which were so ubiquitous in the 90’s. It’s goofy, tender, and kept me beaming from ear to ear. Zootopia (full review) also kept me beaming, and with its refreshingly frank take on otherness and the need to accept one another, it even managed to sneak in a few tears along the way. But Hail Caesar was the complete package: the sort of film that reveals more amazing layers with each successive rewatch. It’s puzzling to me, in a year where La La Land garnered ubiquitous acclaim for its retro Hollywood flare, that so many people seem to have forgotten this gem. Which isn’t to say that I didn’t love La La Land; only that I really really loved Hail Caesar. It has all the hallmarks of the best of the Coens’ oeuvre: delightfully funny, wickedly off-kilter, supremely confident and visually sumptuous. But what makes this a true gem, and possibly even an outlier in their work, is its earnest desire to inspire awe. We can laugh at Tatum’s sexually repressed sailor dance, or Johansson’s synchronized swim in a too-tight mermaid suit, but there’s something seriously impressive — even moving — about the spectacle. For a few moments in the dark of seat 22C, the world feels full of magic and possibility. The world after touchdown? Would that it were so simple.

6. The Act of Killing Award: OJ Made in America w/ 13th and Weiner

This award is reserved for documentaries which shed new light on social or political issues and, to the surprise of no one, 2016 was an excellent year for those. Ava Duvernay’s 13th is a powerful examination of the inherently racist impact of our justice system, and ought to be required viewing. It pairs very nicely with The New Jim Crow. Weiner, on the other hand, pairs nicely with a stiff drink and a sense of deep, political despair. It’s a mesmerizing display of egomania which, largely due to the insane access Weiner granted the filmmakers, manages to communicate the bizarre, indefatigable charisma of its subject. If I’m honest with myself, by the end I was almost rooting for him to win.

For both insight on institutional racism and a portrait of self-destructive charisma, though, OJ: Made in America stands peerless. A five-part series standing at just under 8 hours, it’s a sprawling behemoth that really ought to have been redundant. What need does the infamous OJ trial, one of the most widely covered media events in history, have for further analysis? What stone could possibly have been left unturned? The answer lies in the film’s massive scope. Beginning with the riots in 1960’s LA, it aims to tell not only what happened and why, but what sharp cultural wounds had been opened in the process. It paints OJ in the light he was actually seen by his supporters and detractors: a symbol of race and upwards mobility. Despite countless conscious efforts to personally disavow his symbolic role, it followed him wherever he went. As we discover the world he was brought into, and watch how he pushed against and steered it throughout his career, the deep chasms that separated public opinion become striking and profound. With a keen eye for narrative, and incredible access to virtually everyone involved in the case, this is the filmic equivalent of a page turner. At the end of its behemoth runtime, I would have happily watched more.

For both insight on institutional racism and a portrait of self-destructive charisma, though, OJ: Made in America stands peerless. A five-part series standing at just under 8 hours, it’s a sprawling behemoth that really ought to have been redundant. What need does the infamous OJ trial, one of the most widely covered media events in history, have for further analysis? What stone could possibly have been left unturned? The answer lies in the film’s massive scope. Beginning with the riots in 1960’s LA, it aims to tell not only what happened and why, but what sharp cultural wounds had been opened in the process. It paints OJ in the light he was actually seen by his supporters and detractors: a symbol of race and upwards mobility. Despite countless conscious efforts to personally disavow his symbolic role, it followed him wherever he went. As we discover the world he was brought into, and watch how he pushed against and steered it throughout his career, the deep chasms that separated public opinion become striking and profound. With a keen eye for narrative, and incredible access to virtually everyone involved in the case, this is the filmic equivalent of a page turner. At the end of its behemoth runtime, I would have happily watched more.

5-1: “Best Of” Thematic Pairs

5. Rewriting the story: Moonlight and The Handmaiden

In a year where the lines of battle have been so clearly drawn, it’s tempting to see identity as a sort of deterministic inheritance. Who made you the unwilling heir of your demographic, your social class, your assumed goals? Who defines you? These films respond with resounding conviction: through honesty and determination, you define yourself.

In his intimate and brooding Medicine for Melancholy, Barry Jenkins documented a day in the life of two San Francisco 20somethings, and their fumbling attempts to untangle identity amid issues of class, race, and belonging. In Moonlight he goes the other direction, telling very little but revealing immeasurably more. We watch as Little (Chiron) attempts to unravel the life fate has thrust upon him: growing up penniless and (effectively) parentless in a drug-addled neighborhood of Miami. Too young to understand why he’s being bullied, or even really understand sexuality at all, he is taken in by a drug dealer whose surrogate fatherhood provides shelter from the storm. We watch his life unfold in two subsequent acts: first with the story he chooses for himself out of defensiveness (hardness), and eventually a hint of the story he permits himself to write (softness, love.) This is a gorgeous film, bursting with self-assured style and haunting symbols. I loved the scenes of light and dark; of learning to swim as a sort of baptism into manhood, of the blues and reds and yellows of the city streets he haunts. External forces and textures are constantly coloring Chiron’s outward appearance, but his eyes betray the bright light inside. It’s quiet, revelatory, and solidifies Jenkins as a voice to be reckoned with.

In his intimate and brooding Medicine for Melancholy, Barry Jenkins documented a day in the life of two San Francisco 20somethings, and their fumbling attempts to untangle identity amid issues of class, race, and belonging. In Moonlight he goes the other direction, telling very little but revealing immeasurably more. We watch as Little (Chiron) attempts to unravel the life fate has thrust upon him: growing up penniless and (effectively) parentless in a drug-addled neighborhood of Miami. Too young to understand why he’s being bullied, or even really understand sexuality at all, he is taken in by a drug dealer whose surrogate fatherhood provides shelter from the storm. We watch his life unfold in two subsequent acts: first with the story he chooses for himself out of defensiveness (hardness), and eventually a hint of the story he permits himself to write (softness, love.) This is a gorgeous film, bursting with self-assured style and haunting symbols. I loved the scenes of light and dark; of learning to swim as a sort of baptism into manhood, of the blues and reds and yellows of the city streets he haunts. External forces and textures are constantly coloring Chiron’s outward appearance, but his eyes betray the bright light inside. It’s quiet, revelatory, and solidifies Jenkins as a voice to be reckoned with.

The Handmaiden is stylistically about as far from Moonlight as you could get: there is nothing quiet about it. But through the vibrant filter of his signature style, Park Chan Wook gets at a surprisingly similar conclusion. Sookee, a Korean servant girl born into poverty, is brought to the house of Hideko, a Japanese heiress who seems stuck in a catatonic lack of meaning, waiting helplessly for a loveless marriage to sweep her away. Both of their inheritances dictate the same story: servitude, repression, self-imposed numbness. It’s virtually impossible to explain how the plot progresses without ruining one of the many wonderful twists of its puzzling, double-crossing narrative. Suffice it to say that neither woman goes quietly into that good night. Like Moonlight, the film mingles issues of class and sexuality with gorgeous visuals and a supremely confident sense of pacing and plot. It’s provocative and violent, but also heartfelt and lovely, and a hell of a lot of fun to boot. If Moonlight ends on a delicate question, The Handmaiden ends with a roaring exclamation point: we write our own narratives. We rise up and steer the skin.

The Handmaiden is stylistically about as far from Moonlight as you could get: there is nothing quiet about it. But through the vibrant filter of his signature style, Park Chan Wook gets at a surprisingly similar conclusion. Sookee, a Korean servant girl born into poverty, is brought to the house of Hideko, a Japanese heiress who seems stuck in a catatonic lack of meaning, waiting helplessly for a loveless marriage to sweep her away. Both of their inheritances dictate the same story: servitude, repression, self-imposed numbness. It’s virtually impossible to explain how the plot progresses without ruining one of the many wonderful twists of its puzzling, double-crossing narrative. Suffice it to say that neither woman goes quietly into that good night. Like Moonlight, the film mingles issues of class and sexuality with gorgeous visuals and a supremely confident sense of pacing and plot. It’s provocative and violent, but also heartfelt and lovely, and a hell of a lot of fun to boot. If Moonlight ends on a delicate question, The Handmaiden ends with a roaring exclamation point: we write our own narratives. We rise up and steer the skin.

4. Rewiring the heart: Paterson and Manchester By The Sea

But what if we can’t rewrite the story? What if change is outside our grasp? These films argue for a bulwark that can’t be eroded: the ability to change one’s own perception. Rewiring the heart so nothing, good or bad, can truly uproot it.

In Paterson (full review), the act of rewiring is intentional and optimistic. The titular character lives a life that, by most measures, ought to be a recipe for ennui: stuck with a routine blue collar job in a routine blue collar town, reliving each day with endless repetition. But Paterson chooses to see meaning in life’s tiniest details; each gorgeous, hilarious, and uniquely his own. He lives in a self-imposed rhythm, taking each day as it comes and turning its tiny revelations into poetry. As Jim Jarmusch piles tiny accents and aberrations into his schedule, we see the exceptions that prove the rules — the accumulated weight of wrongnesses that temporarily bring the rhythm to a halt. It’s a deftly revealing balancing act, the filmic equivalent of meditation. Like the best films, it’s about everything and nothing: the inherent selfishness of creative endeavors, the way people in your life act as flavor and counterweight, the unsung heroes who listen more than they speak, the genius of William Carlos Williams, the light of a match and the color blue. It’s visually striking, whimsically funny, subtly fantastical, and imposes a slowness on the audience that I found absolutely refreshing.

In Paterson (full review), the act of rewiring is intentional and optimistic. The titular character lives a life that, by most measures, ought to be a recipe for ennui: stuck with a routine blue collar job in a routine blue collar town, reliving each day with endless repetition. But Paterson chooses to see meaning in life’s tiniest details; each gorgeous, hilarious, and uniquely his own. He lives in a self-imposed rhythm, taking each day as it comes and turning its tiny revelations into poetry. As Jim Jarmusch piles tiny accents and aberrations into his schedule, we see the exceptions that prove the rules — the accumulated weight of wrongnesses that temporarily bring the rhythm to a halt. It’s a deftly revealing balancing act, the filmic equivalent of meditation. Like the best films, it’s about everything and nothing: the inherent selfishness of creative endeavors, the way people in your life act as flavor and counterweight, the unsung heroes who listen more than they speak, the genius of William Carlos Williams, the light of a match and the color blue. It’s visually striking, whimsically funny, subtly fantastical, and imposes a slowness on the audience that I found absolutely refreshing.

Manchester By The Sea (full review) also centers around an inward protagonist, but his quiet contemplation comes less from a desire to slow down than a need to survive. Grief has plagued Lee’s life for years, and he’s learned to wrap it around him like a cocoon. His nephew Patrick, on the other hand, is new to the game. So when Lee’s brother and Patrick’s father, respectively, passes, each respond in notably different ways. Lee shuts out the periphery and focuses on forward motion. Reduces conversation to absolute necessity, looks past every gaze at a 45 degree angle. Patrick assumes the best defense is a good offense, diving headfirst into band practice, friendships, girlfriends, boats. But while these interactions seem meaningful on their surface, there’s something performative about it; a shot aimed to look sincere but still throw the game. I saw this film as a quiet apprenticeship in grief; Lee fumbling to teach Patrick, through osmosis, what his own limitations fail with words. That it’s better to grieve imperfectly and silently, and maybe even destructively, than not at all. To rewire your heart to take things as they come, to strip all artifice and conscious performance and simply experience life’s lows, highs, and (most strikingly) banal plateaus. Wonderfully acted and gorgeously serene, it’s a bitter pill well worth taking.

Manchester By The Sea (full review) also centers around an inward protagonist, but his quiet contemplation comes less from a desire to slow down than a need to survive. Grief has plagued Lee’s life for years, and he’s learned to wrap it around him like a cocoon. His nephew Patrick, on the other hand, is new to the game. So when Lee’s brother and Patrick’s father, respectively, passes, each respond in notably different ways. Lee shuts out the periphery and focuses on forward motion. Reduces conversation to absolute necessity, looks past every gaze at a 45 degree angle. Patrick assumes the best defense is a good offense, diving headfirst into band practice, friendships, girlfriends, boats. But while these interactions seem meaningful on their surface, there’s something performative about it; a shot aimed to look sincere but still throw the game. I saw this film as a quiet apprenticeship in grief; Lee fumbling to teach Patrick, through osmosis, what his own limitations fail with words. That it’s better to grieve imperfectly and silently, and maybe even destructively, than not at all. To rewire your heart to take things as they come, to strip all artifice and conscious performance and simply experience life’s lows, highs, and (most strikingly) banal plateaus. Wonderfully acted and gorgeously serene, it’s a bitter pill well worth taking.

3. Reimagining the present: Sing Street and Swiss Army Man

Film has always been a means of escape, but in 2016 that need has seemed more urgent than ever. These films explore the way one’s imagination, or the capacity to dream, can be used to break free from troubling circumstances. The way the little worlds we build for ourselves can elevate our status within them.

Sing Street should arguably be #1 on this list, because it’s the only film this year that made me both cry and laugh out loud on three separate viewings. It has also been the soundtrack to my life for numerous days on the road. Like Once and Begin Again, Carney’s film is a shamelessly sentimental ode to the transformative power of music. In Once it was the power to bring together; in Begin Again it was the power to create joy. This time, that power is to create hope; the mystical way that playing or hearing the perfect song can transport you, can make you transcend the daily grind and dream for something more. Like any good coming-of-age story, it involves the uncertain guy winning the unattainable girl, and there are plenty of gratifying emotional beats to be had there. But like the shamelessly schmaltzy About Time before it, the central romance here works best as a Trojan Horse for deeper concepts of family, contentedness, and belonging. I love every character in this movie: the parents on the brink of divorce, the misfit kids who find a tribe in the Duran Duran and Joy Division freaks of the world, and particularly the stoner older brother with a bleeding heart of gold. I love the pacing: at just over 100 minutes it never overstays its welcome, but still pauses to give feelings room to breathe. I love the scenes of making music, so intimate and rejuvenating and gloriously 80’s adolescent. Perhaps most crucially, the songs themselves are fantastic. Carney may be a one trick pony, but that one trick contains multitudes, and his powers over it are only growing deeper with time. Finally, always remember: no woman can truly love a man who listens to Phil Collins. I can’t recommend this crowd-pleaser highly enough.

Sing Street should arguably be #1 on this list, because it’s the only film this year that made me both cry and laugh out loud on three separate viewings. It has also been the soundtrack to my life for numerous days on the road. Like Once and Begin Again, Carney’s film is a shamelessly sentimental ode to the transformative power of music. In Once it was the power to bring together; in Begin Again it was the power to create joy. This time, that power is to create hope; the mystical way that playing or hearing the perfect song can transport you, can make you transcend the daily grind and dream for something more. Like any good coming-of-age story, it involves the uncertain guy winning the unattainable girl, and there are plenty of gratifying emotional beats to be had there. But like the shamelessly schmaltzy About Time before it, the central romance here works best as a Trojan Horse for deeper concepts of family, contentedness, and belonging. I love every character in this movie: the parents on the brink of divorce, the misfit kids who find a tribe in the Duran Duran and Joy Division freaks of the world, and particularly the stoner older brother with a bleeding heart of gold. I love the pacing: at just over 100 minutes it never overstays its welcome, but still pauses to give feelings room to breathe. I love the scenes of making music, so intimate and rejuvenating and gloriously 80’s adolescent. Perhaps most crucially, the songs themselves are fantastic. Carney may be a one trick pony, but that one trick contains multitudes, and his powers over it are only growing deeper with time. Finally, always remember: no woman can truly love a man who listens to Phil Collins. I can’t recommend this crowd-pleaser highly enough.

If there’s an opposite of “crowd-pleaser”, Swiss Army Man might be it. Twistedly like Sing Street, it’s a coming-of-age tale, a story about an inward guy pining for an unreachable girl, an ode imagination’s transformative powers, and has an absolutely killer soundtrack. So why is it so polarizing? The key difference lies in the innocence of its leads and the purity of its message. Swiss Army Man is anything but clean. It’s a jubilant bromance between a loner and a corpse; a heartfelt indie which goads you to like it then farts at your praise; a bizarro Where the Wild Things Are where Childish Wonder and footie pajamas become Deeply Repressed Male-ness and a dress made of garbage. An erection is used as a compass. Teeth are used to shave. A dead hand touches a wigged stalker on a bus, and its rigor-mortis clench warms your heart. “Just kiss her already!” you’ll want to shout at the corpse, and it’s never quite clear if you’re joking. This is a truly manic film that loves toying with the audience. And the truths it’s shouting are more elemental than profound: everybody’s awkward, everybody dies. Whether you love it or hate it might depend on exactly which elements you see in your own psyche. I identified more than I’d care to admit.

If there’s an opposite of “crowd-pleaser”, Swiss Army Man might be it. Twistedly like Sing Street, it’s a coming-of-age tale, a story about an inward guy pining for an unreachable girl, an ode imagination’s transformative powers, and has an absolutely killer soundtrack. So why is it so polarizing? The key difference lies in the innocence of its leads and the purity of its message. Swiss Army Man is anything but clean. It’s a jubilant bromance between a loner and a corpse; a heartfelt indie which goads you to like it then farts at your praise; a bizarro Where the Wild Things Are where Childish Wonder and footie pajamas become Deeply Repressed Male-ness and a dress made of garbage. An erection is used as a compass. Teeth are used to shave. A dead hand touches a wigged stalker on a bus, and its rigor-mortis clench warms your heart. “Just kiss her already!” you’ll want to shout at the corpse, and it’s never quite clear if you’re joking. This is a truly manic film that loves toying with the audience. And the truths it’s shouting are more elemental than profound: everybody’s awkward, everybody dies. Whether you love it or hate it might depend on exactly which elements you see in your own psyche. I identified more than I’d care to admit.

2. Recontextualizing the past: Tower and Arrival

Another recurring theme of the year has been that of looking back, of grappling with the aches and sins of our collective past. These films argue that “grappling” is not enough; that by reliving the past we might actually sanctify it, transubstantiate its wrongness into something akin to beauty.

The past Tower concerns itself with carries a particularly painful resonance today. In 1966, a sniper climbed the clock tower at the University of Texas campus, and began firing on any innocent civilian he could find. I don’t know his name, because to Tower’s endless credit, it isn’t remotely concerned with him. Instead, reminiscent of Ari Folman’s wonderful Waltz With Bashir, the documentary acts as group therapy for the tragedy’s survivors, allowing them to relive their memories through a blend of rotoscoped reenactments, intimate interviews, and sparingly used archival footage. The result is gloriously engaging, and perfectly communicates the dread and immediacy of the event; the sudden loss of certainty, the fear that the world is burning. If that sounds heavy, it’s because it is — but that weight soon gives way to lightness. Because at the core, Tower is not about the tragedy itself, but the human response tragedy elicits. It’s about the heroism — or cowardice — of regular folk thrust into terrifying situations. It’s about the things you learn about yourself when everything around you crumbles. Some people find themselves paralyzed by fear; they learn to accept their weakness, to accept that not everyone can save the day. Others find themselves propelled by a force they didn’t know existed; they run selflessly into harm’s way to protect, assist, or even simply empathize with a person in need. Through it all we see a tapestry of human love and human fear, woven by real, imperfect people in immaculate detail. Together they rewrite the narrative arc of the past, from one of devastating loss to one of empathy and shining connection. I loved every minute of this movie.

The past Tower concerns itself with carries a particularly painful resonance today. In 1966, a sniper climbed the clock tower at the University of Texas campus, and began firing on any innocent civilian he could find. I don’t know his name, because to Tower’s endless credit, it isn’t remotely concerned with him. Instead, reminiscent of Ari Folman’s wonderful Waltz With Bashir, the documentary acts as group therapy for the tragedy’s survivors, allowing them to relive their memories through a blend of rotoscoped reenactments, intimate interviews, and sparingly used archival footage. The result is gloriously engaging, and perfectly communicates the dread and immediacy of the event; the sudden loss of certainty, the fear that the world is burning. If that sounds heavy, it’s because it is — but that weight soon gives way to lightness. Because at the core, Tower is not about the tragedy itself, but the human response tragedy elicits. It’s about the heroism — or cowardice — of regular folk thrust into terrifying situations. It’s about the things you learn about yourself when everything around you crumbles. Some people find themselves paralyzed by fear; they learn to accept their weakness, to accept that not everyone can save the day. Others find themselves propelled by a force they didn’t know existed; they run selflessly into harm’s way to protect, assist, or even simply empathize with a person in need. Through it all we see a tapestry of human love and human fear, woven by real, imperfect people in immaculate detail. Together they rewrite the narrative arc of the past, from one of devastating loss to one of empathy and shining connection. I loved every minute of this movie.

Arrival (full review) reaches a similar conclusion, albeit through drastically different means. Denis Villeneuve’s moody sci-fi follow-up to the personally disappointing Sicario (full review), Arrival strikes the perfect balance between arthouse flick and dazzling blockbuster. It follows the classic formula of vintage science fiction, thrusting characters into extraordinary situations in order to reveal tiny mysteries about our own, ordinary lives. To say much of anything about the plot would be to spoil it; in ways that will become self-evident when you watch it, it succeeds precisely where Interstellar (full review) failed. But what left me breathless was how many other, contradictory ways it succeeds on the side. In the sense that minimalism is a virtue, this is a minimalist film: CG is used sparingly and to haunting effect, and exposition never threatens to trip up its emotional rhythm. In many ways, though, this is also a maximalist spectacle. It’s a hypnotic fugue through memory and loss, with a heavy doses of Terrance Malick and hints of Eternal Sunshine. The opening moved me deeply, and it only pays off more as the story unfolds. It’s a story about the oneness of all things, about the beauty of loss and the way, with a slight shift in perspective, every painful moment can be seen as an accent or notch in one living, breathing human experience. I found it mesmerizing.

Arrival (full review) reaches a similar conclusion, albeit through drastically different means. Denis Villeneuve’s moody sci-fi follow-up to the personally disappointing Sicario (full review), Arrival strikes the perfect balance between arthouse flick and dazzling blockbuster. It follows the classic formula of vintage science fiction, thrusting characters into extraordinary situations in order to reveal tiny mysteries about our own, ordinary lives. To say much of anything about the plot would be to spoil it; in ways that will become self-evident when you watch it, it succeeds precisely where Interstellar (full review) failed. But what left me breathless was how many other, contradictory ways it succeeds on the side. In the sense that minimalism is a virtue, this is a minimalist film: CG is used sparingly and to haunting effect, and exposition never threatens to trip up its emotional rhythm. In many ways, though, this is also a maximalist spectacle. It’s a hypnotic fugue through memory and loss, with a heavy doses of Terrance Malick and hints of Eternal Sunshine. The opening moved me deeply, and it only pays off more as the story unfolds. It’s a story about the oneness of all things, about the beauty of loss and the way, with a slight shift in perspective, every painful moment can be seen as an accent or notch in one living, breathing human experience. I found it mesmerizing.

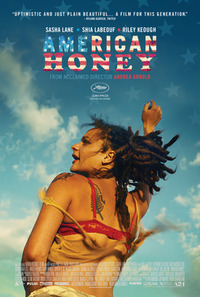

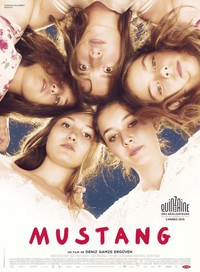

1. Reclaiming the future: American Honey and Mustang

Every response so far — changing the narrative, shifting the frame of reference, imagining a better present, baptizing a painful past — has been mostly internal. Sometimes, though, the pressures of the world call for a drastic external response. To break free from repression. To reclaim the future. Two films this year, both directed by women and starring teenaged girls, showcased that unquenchable drive towards freedom. In a year desperately lacking in hope, they carried an urgency that stuck with me long after other messages dissipated.

From a distance, American Honey (full review) doesn’t look much like a story of freedom. If anything, its trailer implies a cautionary tale of redemption; a hip-hop Bonnie and Clyde gone horribly wrong. Star escapes the poverty of the deep south to join a roving mag crew — heavily-pierced hustlers who travel from town to town, shilling unwanted magazine subscriptions before eventually graduating to more forceful, intimate, and scarring confrontations. What made me fall in love with American Honey isn’t that it avoids the classic redemptive arc — there are highs and lows in Star’s journey to be had, questionable decisions on stark display. It’s that it paints these highs and lows as something spiritual and necessary. This is a generous film. The sort that truly believes in the goodness of its subjects. Hurting, naive, flawed, reckless, and prone to make a few more bad decisions after the credits roll, but good to the core. It tells us that Star will end her journey a wiser person than when she began, and that she’ll make it through her circumstances alive. That Jake is more than a white trash fuck up with a rat tail and cheap suit; or, better, that no one needs to be “more” than anything to be fully alive. That those rowdy kids you see in the parking lot, cursing in front of your children, chugging $3 liquor, blasting hip hop too loudly and hitting too hard — they aren’t Prodigal Sons waiting to be saved in Act III. They’re already on the van to salvation, rickety and swerving. Andrea Arnold observes her crew with the delicate touch of an anthropologist, treating her bruised subjects with a near-perfect blend of naturalism and style. Through the gentle lull of the open road, the thrill of an ear-splitting radio radio beat, and sex scenes so delicate the sunlight practically fogs up the lens, there’s a gorgeous, tactile empathy forever on display.

From a distance, American Honey (full review) doesn’t look much like a story of freedom. If anything, its trailer implies a cautionary tale of redemption; a hip-hop Bonnie and Clyde gone horribly wrong. Star escapes the poverty of the deep south to join a roving mag crew — heavily-pierced hustlers who travel from town to town, shilling unwanted magazine subscriptions before eventually graduating to more forceful, intimate, and scarring confrontations. What made me fall in love with American Honey isn’t that it avoids the classic redemptive arc — there are highs and lows in Star’s journey to be had, questionable decisions on stark display. It’s that it paints these highs and lows as something spiritual and necessary. This is a generous film. The sort that truly believes in the goodness of its subjects. Hurting, naive, flawed, reckless, and prone to make a few more bad decisions after the credits roll, but good to the core. It tells us that Star will end her journey a wiser person than when she began, and that she’ll make it through her circumstances alive. That Jake is more than a white trash fuck up with a rat tail and cheap suit; or, better, that no one needs to be “more” than anything to be fully alive. That those rowdy kids you see in the parking lot, cursing in front of your children, chugging $3 liquor, blasting hip hop too loudly and hitting too hard — they aren’t Prodigal Sons waiting to be saved in Act III. They’re already on the van to salvation, rickety and swerving. Andrea Arnold observes her crew with the delicate touch of an anthropologist, treating her bruised subjects with a near-perfect blend of naturalism and style. Through the gentle lull of the open road, the thrill of an ear-splitting radio radio beat, and sex scenes so delicate the sunlight practically fogs up the lens, there’s a gorgeous, tactile empathy forever on display.

The same could be said for Deniz Ergüven’s directorial style in Mustang (full review) (technically 2015, but foreign releases come late to the US and, as established, I make the arbitrary rules here!) Indeed, the parallels to Arnold’s work run deep. Set in modern day Turkey, the film tells the story of a group of sisters raised in a strict religious household. Like American Honey, it’s about liberation and the myriad choices we navigate en route. It’s also a film that breathlessly defies expectations. Looking at the poster, you might reasonably come to one of two conclusions: note the cast and assume it’s a charming portrait of sisterhood, or note their stares and assume it’s a gut-wrenching drama. What’s remarkable about Mustang is how perfectly it does both, and how much more it finds room to do on the side. Tonally it has shades of Sofia Coppola, but in scope it’s more like a Turkish Persepolis: a keenly observed coming of age story, an intimate glimpse of an underseen culture, a damning finger at the oppression polluting said culture, a cry for help and a shout of resilience in the same breath. Even the weightiest symbols (the wall, the gun, a meticulously folded sheet), when not devastating us, have the power to make us smile. If American Honey feels like an anthropological study, Mustang feels like a secret diary, striking that impossible balance which only stories rooted in truth can maintain: to simultaneously mock, mourn, and miss the same thing. Damning outrage at what it did, smiling familiarity with the particular way it did it, nostalgia for how it was yours to feel. A cathartic cleanse of things lost in the fire, and a rallying cry for brighter futures ahead.

The same could be said for Deniz Ergüven’s directorial style in Mustang (full review) (technically 2015, but foreign releases come late to the US and, as established, I make the arbitrary rules here!) Indeed, the parallels to Arnold’s work run deep. Set in modern day Turkey, the film tells the story of a group of sisters raised in a strict religious household. Like American Honey, it’s about liberation and the myriad choices we navigate en route. It’s also a film that breathlessly defies expectations. Looking at the poster, you might reasonably come to one of two conclusions: note the cast and assume it’s a charming portrait of sisterhood, or note their stares and assume it’s a gut-wrenching drama. What’s remarkable about Mustang is how perfectly it does both, and how much more it finds room to do on the side. Tonally it has shades of Sofia Coppola, but in scope it’s more like a Turkish Persepolis: a keenly observed coming of age story, an intimate glimpse of an underseen culture, a damning finger at the oppression polluting said culture, a cry for help and a shout of resilience in the same breath. Even the weightiest symbols (the wall, the gun, a meticulously folded sheet), when not devastating us, have the power to make us smile. If American Honey feels like an anthropological study, Mustang feels like a secret diary, striking that impossible balance which only stories rooted in truth can maintain: to simultaneously mock, mourn, and miss the same thing. Damning outrage at what it did, smiling familiarity with the particular way it did it, nostalgia for how it was yours to feel. A cathartic cleanse of things lost in the fire, and a rallying cry for brighter futures ahead.

Here’s to…

…more unlikely, unrealistic, baseless, vapid, messy, sprawling, necessary, mysterious, beautiful, transformative, full-blooded dreams of bright futures ahead.