More ramblings: I’ve been doing this a long time! Check out my 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, and 2014 lists.

Podcast: you can listen to my flat Top 10 list on The Spoiler Warning.

Introduction

Each year I vow to make my Best Of list simpler than the last, and each year I completely fail. I can’t find any reason for this continuing arms race, beyond good old-fashioned self torture. What started in the podcast-only days as a humble Top 5 became a written Top 10 with a growing number of honorable mentions. When it eventually became impossible to extricate winners from runners-up, I sidestepped the problem with a hybrid list of singletons and pairs. By the next year all singletons were gone, and my list was comprised of 10 thematic pairs. Last year, after escalating yet again to 12 thematic pairs framed around one central conceit, I decided I’d had enough. Writeups that I used to publish in early January were now lingering past Valentine’s day. The dam would have to break in 2020. I would learn to keep things simple.

And in some ways, I’ve held to that simplicity constraint. There will be no grand central theme this year, no lone narrative throughline; though, in truth, that’s less about conviction and more about 2019. Because if there was one recurring theme last year, for me, it was something about the fundamental uselessness of epiphanies: the realization that things that matter rarely adhere to one consistent philosophy. I found it in personal and professional arenas: character traits I’d been proud of started to show their uglier sides, while others I’d seen as shortcomings morphed into incidental strengths. If ever I felt I had something pegged (“X is The Real Problem™”, “If only everyone would be more like Y”), a glaring counterexample was surely right around the corner, waiting to make an ass of me. Was I empathetic or manipulative, friendly or phony, witty or insufferable, loyal or cowardly, determined or short-sighted? Often, I’d find, I was both simultaneously. I could see both perspectives. I could be made better by them.

I felt it, too, in the country writ large: the failure-prone predictions, flaccid hyperboles, inscrutable see-saws between anti- and climax. So many strange bedfellows were made and dissolved this year. That desperate desire to crown anyone a “hero”: a Bush-era FBI Director, a skeevy LA lawyer, even Michael damn Cohen for a sad fifteen minutes. That unpleasant feeling when the story ended in failure; or, more often, ended in some limp middle ground between failure and success. But, then, the equal-or-greater failures of that “moderate” counter-impulse: “he won’t be so bad”, “nothing will come from this”, “he’s a veteran statesman, not a political hack!” Time and time again, those things of which I felt most certain were proven false, including my bias against certainties. There will be an impeachment. There will be no impeachment. There will be one, but it will be detrimental to our discourse; there will be none, and that will be detrimental to our discourse. So many opinions, persuasively argued by people I admired, and depending on the time of day I could internalize any. Was it a year of hope, of gears slowly whirring after endless gridlock? Or was it a year of growing callousness, of a spiritual divide so calcified it renders the very notion of “hope” quaint?

I was angry, often, in 2019—glued to a screen when I should have been sleeping, seething with hypothetical arguments and blistering rebuttals. I was also extraordinarily happy in 2019, both in the Instgrammable sense and the more important, lived-in variety. I learned, somehow, to be both more and less certain of things. Or maybe it was to never pit one type of certainty against another, deeper type; to find more stable footing amid the not-knowing. I know that’s vague, and maybe unintelligible. It wasn’t a year that lent itself to clarity, either.

About the year in film, however, I’m totally clear: 2019 was a goldmine. I saw more contemporary releases than usual over the calendar year (121 by my present tally), and loved a high percentage.1 Judging by critical year-end roundups, I’m not alone in feeling that this was an unusually strong roster. Seasoned auteurs presented late-career-high works to a mainstream audience, and first-time directors took festivals by storm. There were formalist dramas and rip-roaring genre flicks, brutal documentaries and biting comedies, abrasive character studies and heart-melting melodramas and a whole lot of something wistfully in-between. The Palme d’Or winner was somehow also a financial success, Netflix releases were routinely wonderful (and widely seen!), and even the superhero movies proved critically…well, if not beloved, at least worthy of conversation. There was an abundance of period pieces—nearly half of my list, if you’re lenient about definitions—but somehow, at the same time, I’m not sure I’ve seen a year so rooted in hyper-modern sentiment: economic anxieties, social malaise, that feeling of collective unclenching. Whatever your itch, there was at least one masterpiece to scratch it.

So while this list is simpler than last year’s, it’s also quite a bit longer: at the time of my writing this intro it’s comprised of 32 films, grouped into 10 Key Ideas I found personally moving. Many of these ideas, fittingly, are about the interconnectedness of people and societies; also fitting is the degree to which they seem to rebut each other. And as usual, the grouped ranking process proved infuriatingly fuzzy. The more I liked an entry the more it elevated its group (with my favorite entry being named first in the group). That said, a group full of solid A’s would often beat one with a lone A+. Sometimes the very act of synthesis elevated my view of a group’s composite members, which I’d argue is the point of this silly exercise. If you desperately need a flat ranking you can listen to the podcast for a direct Top 10 (documentaries excluded). But really, the order hardly matters: all movies listed here are very very good, and the vast majority I’d deem “excellent.” It was a hell of a year.2

With that, here are my 10 Key Ideas of 2019:

10: Society is people and people are messy: American Factory, Honeyland, Monos ↯

9: …yet fanaticism feeds on isolation: Jojo Rabbit, Young Ahmed, Joker ↯

8: We can honor a legacy without glamorizing its shortcomings: Pain and Glory, Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood, The Irishman ↯

7: …but there’s something intoxicating about self-destruction: Uncut Gems, Her Smell, The Souvenir ↯

6: To mourn death is to embrace some fundamental connectedness: Paddleton, Blackbird, The Farewell, Midsommar ↯

5: That connection is unimaginably vital: Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Little Women, Queen & Slim, 5B ↯

4: …but a broken connection disorients: Marriage Story, Transit, The Lighthouse ↯

3: Capitalism numbs the soul: Parasite, Us, Sorry We Missed You ↯

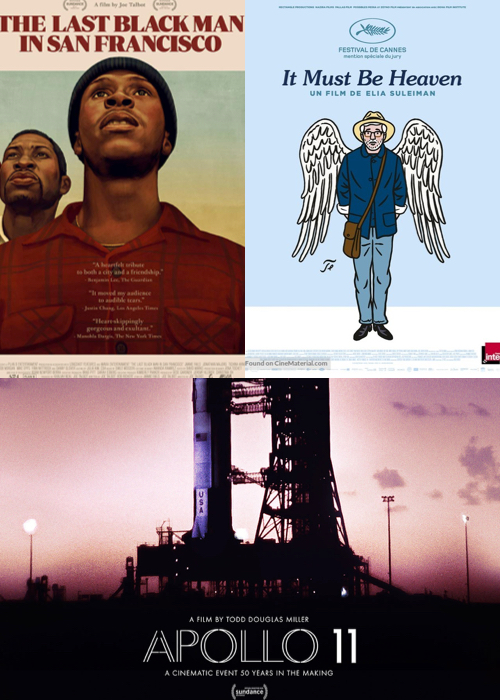

2: Longing is its own type of beauty: The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Apollo 11, It Must Be Heaven ↯

1: There is transformative power in confronting the past: Honey Boy, Ad Astra, Leaving Neverland ↯

10. Society is people and people are messy: American Factory, Honeyland, Monos

Like most worthwhile ideas, this first one sounds exceedingly obvious: beyond all layers of theory or numb abstraction, when we talk about socioeconomic issues what we’re really talking about is the behavior of people—individuals with irrational feelings, desires, egos. So it stands to reason that small groups of people, brought in close proximity, might embody the same polarizing characteristics we see in our politics.

Like most worthwhile ideas, this first one sounds exceedingly obvious: beyond all layers of theory or numb abstraction, when we talk about socioeconomic issues what we’re really talking about is the behavior of people—individuals with irrational feelings, desires, egos. So it stands to reason that small groups of people, brought in close proximity, might embody the same polarizing characteristics we see in our politics.

In American Factory, documentary filmmakers Steven Bognar and Julia Reichert spend three years following the evolution of the newly-opened Fuyao Glass America, an Ohio-based automotive manufacturing plant owned by a Chinese mega-corporation. What follows is a bit like watching the past few decades unfold in a Petri dish: shared optimism buckling under capitalistic pressure to frantic whip-cracking and discontentment; the earnest desire to unionize becoming muddied by a protect-our-own brand of xenophobia; the daily tug-of-war between globalist ideals and local realities. There’s a certain magic to this work, and it lies in the camera’s near-omnipresent access. Whether in a backyard BBQ or a union-busting board room, it coaxes its subjects into saying the quiet bits out loud.

Access is also a superpower of Honeyland, though it may not look it at the start. Following a year in the life of beekeeper Hatidze Muratova, the documentary—by Tamara Kotevska and Ljubomir Stefanov—appears, at first blush, to be a slice-of-life character study, set in a quiet Macedonian village. Collecting honey by day and tending to her ailing mother by night, Hatidze has settled into a comfortable (if admittedly lonely) groove. When a raucous family moves in next door, though, that routine is threatened. As try their own hand at beekeeping, and tensions start to mount, we’re confronted with more universal concerns: can we find a way to live harmoniously with each other and with nature? And if not, is there still value in making the attempt? With its laser-sharp focus and stunning color palette, it’s a journey that’s better felt than described.

Speaking of color palettes, can any work of fiction this year top the oranges and blues of Alejandro Landes’ Monos? A sort of modern retelling of Lord of the Flies, the film centers around a small militia in the mountains of Colombia, where eight teenagers, armed to the teeth, are tasked with guarding a single hostage (presumably foreign, presumably rich). Tensions develop in isolation, and factions begin to form: the ruthless vs the empathetic, the loyal vs the disloyal. As we watch once-innocent bystanders fall under the spell of an erratic demagogue, signing on to horrific acts in the name of “unity” and “strength”, it’s temping to wonder how much of this credulity towards violence is hard-wired…and whether it’s even possible to reverse.3

9. …yet fanaticism feeds on isolation: Jojo Rabbit, Young Ahmed, Joker

While a small group of people can reflect society at large, they don’t always reflect it accurately. Particularly when they’re buffered from the outside world. Three films this year used very different tacts to show the way

isolation begets a sort of funhouse mirror, creating a dangerously warped image of reality. Empathetically depicting that distortion field without excusing those who act on it is an inherently risky endeavor. So it shouldn’t be surprising that each of these was met with polarized reactions—often outright controversy—on initial release.

While a small group of people can reflect society at large, they don’t always reflect it accurately. Particularly when they’re buffered from the outside world. Three films this year used very different tacts to show the way

isolation begets a sort of funhouse mirror, creating a dangerously warped image of reality. Empathetically depicting that distortion field without excusing those who act on it is an inherently risky endeavor. So it shouldn’t be surprising that each of these was met with polarized reactions—often outright controversy—on initial release.

Jojo Rabbit is, by far, the broadest of the bunch, which also makes it the easiest target for ridicule. Taika Waititi’s self-proclaimed “anti-hate satire” about a young boy, his imaginary Hitler, and the Jewish girl that haunts his attic, has been alternately called toothless and tasteless, too light to be damning and too heavy to be sweet. Personally, I found it an absolute joy, and precisely the sort of satire 2019 demanded; a funhouse mirror held up to a funhouse mirror, it acts as a sort of reductio ad absurdum against the foundations of hate—not the genuine motives of hateful people, that is, but the self-aggrandizing ideologies they invent to cloak their bile in “facts”. In an era where anyone can opt into their own bespoke echo chamber, Waititi reminds us that one-sided conversations are for overgrown children. Like imaginary heroes and monsters in the closet, the strongest antidote might just be sunlight.

While Young Ahmed carries a similar message, its execution is arguably the polar opposite, replacing broad satire with a near-claustrophobic realism. In other words, it’s everything the Dardenne brothers (L’enfant; Two Days, One Night; The Kid with a Bike) do best. The film follows Ahmed, a Belgian teen of Arabic descent who, despite the interventions of his loving Muslim family, finds himself becoming increasingly radicalized. As we watch Ahmed grapple with his contradictory impulses—the violent “logical conclusions” his mentor has convinced him he believes, the stern inner voice that resists them nonetheless—we’re forced to walk a tightrope between horror and hope. It’s an exhilarating crash course in empathy.

Joker opts to severs that tightrope with a pair of bloody scissors. Critics may debate the degree to which the film sympathizes with Phoenix’s troubled antihero, and they’re well within their rights to do so. For my money, though, there is no ambiguity. From the unsettling opening to the hellish conclusion, I felt nothing but dread watching Phillips’ take on the iconic clown prince. Behind its early Scorsese trappings lies an eerily modern nightmare: a deluded individual grows increasingly unhinged, and the world not only ignores his red flags, it embraces them as some skewed statement of post-post-post-ironic rebellion. It’s Pepe memes taken to their terrifying extreme, a cynical detachment so total it mistakes the random actions of a madman for political bravery. When Arthur Fleck has all but vanished and the Joker greets his rabid fans, it isn’t him I’m horrified of. It’s the world that we share.

8. We can honor a legacy without glamorizing its shortcomings: Pain and Glory, Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood, The Irishman

If art is in constant conversation with society, and society is influenced by the art it consumes, a prolific artist might live long enough to be on both sides of the conversation. In 2019, we saw that phenomenon play out onscreen. Three iconic (and heavily-imitated) directors not only released their best films in years, they grappled with their own creative legacies in the process.

If art is in constant conversation with society, and society is influenced by the art it consumes, a prolific artist might live long enough to be on both sides of the conversation. In 2019, we saw that phenomenon play out onscreen. Three iconic (and heavily-imitated) directors not only released their best films in years, they grappled with their own creative legacies in the process.

Pain and Glory is, admittedly, the gentlest of the bunch. Imbued with Almodovar’s signature brand of lush romanticism, the film is less grappling with his legacy than it is dancing with it. Still, there’s a weariness that belies its loveliness. Antonio Banderas, playing a thinly-veiled Almodovar, carries it most obviously in the present-tense, as pain leads to heroin addiction leads to total abdication of duty. But it’s hiding in the past as well: in the lovers he’s let go for the sake of art, in the messy realities he’s swept under the rug of fantasy. It’s as if he’s saying, “Here is the world I invented for you, in all of its decadent splendor. And here is why the other world—the truth I’d meant to escape from—is no less sublime.”

To Tarantino the past is the fantasy, and he’s tearing down the set. While Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood is set long before the Weinstein-adopted wunderkind was making movies, it’s hard not to read it as a dark self-reflection. Consider Cliff Booth, the stuntman whose loyalty and wit can’t quite restrain a propensity for violent provocation; or Rick Dalton, the one-time Hollywood hotshot who finds himself in a brave new world that has less and less use for him. Manic and swaggering, impossibly cool and woefully out of touch, suave on the surface but with fury underfoot, they’re dinosaurs who are coming to terms with extinction. They even know, on some level, that it’s the way it should be. Sometimes the old has to die so the new can have a go at it. Still, who can resist one final joyride?

When the cast of The Irishman was first announced, it appeared Scorsese had caved to a similar temptation, and was reuniting the band for one last hurrah. By the end of its 180-minute runtime, though, it’s clear that Marty didn’t set out to make a remix so much as a funeral dirge. A somber takedown of the gangster lifestyle his own films helped (perhaps inadvertently) glamorize, the historical epic is less Goodfellas than it is late-season Sopranos: a brooding, often gleefully uncool character study that seems tailor-made to frustrate its more bloodthirsty fans. Not Henry Hill waxing nostalgia for the glory days, but Uncle Junior sitting by the window, admiring birds. Where I felt Wolf of Wallstreet indulged too much in the high points, this one feels like a hangover from the opening frame. It’s less about crime than it is about a very American brand of emptiness—about the things you might lose in your quest for success, and the impossibility of later retrieving them.

7. …but there’s something intoxicating about self-destruction: Uncut Gems, Her Smell, The Souvenir

Still, there’s a reason we glamorize bad behavior: it’s riveting. Whether television celebrity or problematic friend, there’s a certain charisma or allure that comes with damaging behavior. In small doses, that allure can be a vehicle for empathy. Give it too much power, though, and it might pull you down with it.

Still, there’s a reason we glamorize bad behavior: it’s riveting. Whether television celebrity or problematic friend, there’s a certain charisma or allure that comes with damaging behavior. In small doses, that allure can be a vehicle for empathy. Give it too much power, though, and it might pull you down with it.

The Safdies know a thing or two about destructive personalities; from Daddy Longlegs on, it’s arguably been their raison d’être. But none of the guerilla duo’s antiheroes have been quite like Sandler’s Howard Ratner, and nothing before Uncut Gems has made imploding this mesmeric. Jeweler by day and gambler by night, Ratner’s life is like a Greatest Hits collection of ill-advised decisions—when he finds himself dug in a hole, he triples, quadruples down. With its pitch-perfect tone and meticulous attention to detail, though, the film never lets me hate Howard even as the rational part of me begs for it. Instead, it gives me permission to inhabit him. To feel the anguish of his losses, the thrill of the chase, and an unceasing anxiety that blots out the sun.

The only film this year that might have been more anxiety-inducing was Her Smell. Like Sandler, Elisabeth Moss imbues her calamitous protagonist with a magnetic ferocity. In fact, her punk icon Becky Something shares a number of Howard’s traits. Undeniably charismatic and infuriatingly unpredictable, she’s an addict willing to sacrifice anything (and anyone) for the barest hint of a fix. In a brief window that gave us no shortage of destructive musician stories (Vox Lux, Teen Spirit, Wild Rose, Rocketman), Alex Ross Perry’s vision stands absolutely peerless. No one else brings us remotely as low, and no one else strikes such an earned catharsis.

As The Souvenir shows us, though, addiction is not always about highs and lows. Eventually it becomes a matter of stasis. Inspired by writer/director Joanna Hogg’s own experiences in film school, it tells the story of a young aspiring filmmaker, Julie, who falls for an enigmatic older man, Anthony. While addiction takes many forms in this film, perhaps the most striking is the relationship itself: it’s toxic and unsettling, and Julie can’t seem to quit it. Even as Anthony grows increasingly cruel. He mocks her intelligence, berates her ideas, leaves her alone for days only to return in silence. His is a chilly sort of gaslighting I’d never seen put to screen, and the film carries a similarly chilly aesthetic. Yet, through Julie/Joanna’s eyes, we understand on some level why she returns to that well. And it renders her eventual liberation all the more cathartic.

6. To mourn death is to embrace some fundamental connectedness: Paddleton, The Farewell, Blackbird, Midsommar

You could make a case that art always hangs around the periphery of death, a subject so universal it’s become a cliché. This year, though, a much more specific idea about mortality was percolating. It has something to with coming to terms with ending one’s life: with rendering it, on some level, a positive choice. And sharing that happysad burden.

You could make a case that art always hangs around the periphery of death, a subject so universal it’s become a cliché. This year, though, a much more specific idea about mortality was percolating. It has something to with coming to terms with ending one’s life: with rendering it, on some level, a positive choice. And sharing that happysad burden.

Paddleton is the least “cinematic” treatment of death on this list, but I’d posit it’s also the truest. A gentle two-hander between Ray Romano and Mark Duplass, the film (directed by frequent Duplass collaborator Alex Lehmann) follows the Brothers’ usual aesthetic: low-key, heavily improvised, centered around a few emotional turning points in a character’s life. But while their films tend to focus on life’s smallest moments, Paddleton sets its sights on one larger than life. Which is to say, death. When Michael (Duplass) learns he is dying of stomach cancer, he decides to end his life on his terms. He and his best friend Andy (Romano) embark on a roadtrip, to the one pharmacy still offering suicide medication. At times hilariously uncomfortable and heartbreakingly earnest, their journey unfolds more or less exactly as you’d expect. Yet I cried more in the process than at anything else this year.

A close second in the waterworks department is Roger Michell’s Blackbird, whose plot echoes Paddleton in so many ways you’d think they were separated at birth. An aging mother (Susan Sarandon) is dying of ALS, and she’s gathered her adult children for one last celebration. In tone, though, the two couldn’t be more different: if the Duplass dictum is “less is more”, Michell (of Notting Hill fame) says “subtlety be damned, more is always more”. The result—a star-studded ensemble piece with twice as many impassioned monologues as it has characters to give them—could easily have veered into melodrama. Hell, maybe it did. I was too busy getting the dust out of my eyes to notice. Sometimes understatement is overrated; sometimes you need a good cry and a big family hug.

Skim the synopsis of Lulu Wang’s The Farewell and you might think you’re in for another matriarchal hug: a family learns their Nai Nai is dying of cancer, and must travel to China to say goodbye. The difference? Unlike Sarandon, Zhao Shuzhen’s Nai Nai doesn’t know that she’s dying—and the family has no intention of telling her. The result is something almost impossible to pin down to a single genre: too somber for comedy, too uncomfortable for melodrama, too overflowing with love for a formalist exercise. What it is, instead, is a miniature miracle; a film that manages to be both a deeply personal meditation on family and loss, and a glimpse of Chinese culture through a completely novel lens. Always hovering in some space between access and remove, insider and outsider—echoing, in other words, the immigrant experience. That duality extends to its emotional conclusion, as it argues that everything—even loss, even chosen isolation—might be shared and spread translucent.

No film this year visualized that act of sharing quite like Midsommar. After three realistic takes on mortality, Ari Aster’s psychedelic follow-up to Hereditary might seem a strange companion piece. But I’d argue it’s the perfect coda; a jaunt through the inner-contradictions of grief, as seen through a folk horror kaleidoscope. From its dread-infused opening to its crescendo of a conclusion, death is a constant for Florence Pugh’s Dani. What eventually changes is how she experiences it: celebrated in blinding bright, purposeful, surrounded.

5. That connection is unimaginably vital: Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Little Women, Queen & Slim, 5B

Human connection can’t slow death. Nor can it fix a broken world, cheery slogans notwithstanding. Love has never been an antidote for pain. At its best, though, it can sometimes be a means of sanctifying pain, of rendering shared hardship into a sort of testimony. Four films this year explore the way love can act as a bulwark of warmth against an uncaring world.

Human connection can’t slow death. Nor can it fix a broken world, cheery slogans notwithstanding. Love has never been an antidote for pain. At its best, though, it can sometimes be a means of sanctifying pain, of rendering shared hardship into a sort of testimony. Four films this year explore the way love can act as a bulwark of warmth against an uncaring world.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Céline Sciamma’s exquisite romance set in 18th century France, might be the purest distillation of that concept. Here, love doesn’t only warm, it burns; a pull so irresistable it verges on hypnotic. An unlikely love story between a soon-to-be-wed young woman and the artist hired to secretly paint her, it has this rich ephemerality that feels trite when put in words4. Like Call Me By Your Name, it’s less about the particulars of love than what love does to you, what it catalyzes inside. To Mariann and Héloïse, it’s a means of self-determination, a permission to truly want—in a world where desire is only permitted to flow in the opposite direction.

In Little Women, that “wanting” part of romance takes many forms. Meg wants to settle with a loving man in poverty, despite her grandmother’s insistence that wealth is all that counts. Jo wants to settle with no one, to pursue her dreams in the unthinkable singular. And Amy, perhaps most interestingly, wants almost precisely what the world tells her to want; and she struggles to keep the banality of the latter from diluting the power of the former. Beth…well, if you’ve read the books, you already know her story. For all of them, though, the romantic connection comes second to a stronger, familial bind. What strikes me about Greta Gerwig’s lovely adaptation is its infectious vibrancy; how effortlessly it seems to mine every ounce of life for joy. There’s a warmth to the March family that elevates everything they touch, that stands as a rebuke to the winter outside.

Queen & Slim also finds warmth in defiance, but its subject matter is painfully, tragically current. A self-described subversion of the Bonnie & Clyde myth, Melina Matsoukas’s film follows two black lovers (Queen and Slim) who, after shooting a police officer in an act of self defense, find themselves on the run from the law. Like just about every variant of the myth they inhabit, our lovers seem to exist on two planes at once: there’s the real couple, desperately fleeing a brutalizing police state, and their media doppelgängers, a swaggering invention of public imagination. Both sets of couples evolve in surprising ways—in one of my favorite scenes in the film, they’re shown in stark juxtaposition. While the public couple challenges us more overtly, the private one tees up difficult questions of its own: is their love a biproduct of their trauma, or an inevitable conclusion that trauma only helped tease out? But at a certain point, the causal arrow ceases to matter. In the present there is pain, and they’ve found a way to carry it.

Even if, like the subjects of 5B, they know it to be fleeting. Dan Krauss and Paul Haggis’ stirring documentary is centered around an AIDS ward in San Francisco General, opened just as the crisis was revealing itself to be an epidemic. The ward was rooted in a core philosophy: to never forget a person’s humanity in the name of “containment.” At a time when public panic had reached a fever pitch, and even the medical community was divided on risk, the caregivers of Ward 5B bravely chose love. Speaking to their patients without buffer of glass, administering medicine without chilly HAZMAT suits, holding the hands of the dying glove-free. It was a powerful statement, and one which had virtually nothing to do curing the disease. Rather, it was about instilling a togetherness that made suffering bearable. Jackson Browne and Leslie Mendelson sum it up best in the criminally overlooked song they penned for the picture: “Sometimes all anybody needs is a human touch.”

4. …but a broken connection disorients: Marriage Story, Transit, The Lighthouse

Companionship is a powerful drug. When it’s working, a relationship can ground us, orient us, like nothing in the world. But when it’s misaligned, that same force can prove extremely destabilizing.

Companionship is a powerful drug. When it’s working, a relationship can ground us, orient us, like nothing in the world. But when it’s misaligned, that same force can prove extremely destabilizing.

Sometimes love can do both simultaneously. At first glance, Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story might seem perversely misnamed: opening in a dour mediator’s office, it appears much less concerned with Charlie and Nicole’s marriage than it is with its grisly undoing. After all, the plot is almost entirely about discord: courtroom battles a la Kramer vs. Kramer, Bergman-esque shouting matches that leave holes in the drywall. It is, in many ways, a truly depressing story; a cautionary tale of losing one’s center and finding every relational instinct flipped on its head. But while there’s sadness in the arc of it, there’s a real, human joy in its specific details—often charming, absurd, even uproariously silly. That joy is what made me fall head over heels for this picture. Never a stranger to caustic romance, Baumbach has now proved himself equally adept at mining acrimony for sweetness. It helps that his leads give two of the best performances of the year. Even at their worst, we see glimmers of the same love that held them together.

In Transit, those glimmers are murky from the start. A romance of sorts between émigrés-in-waiting, Christian Petzold’s adaptation is as beguiling as it is beautiful. As with the 1944 novel before it, Petzold sets his characters in a port city in France, awaiting permission to flee a Fascist German occupation. Unlike the novel, though, his film isn’t set in the 40’s; it’s set in present day. Or vaguely present, at any rate: like everything else about our protagonist’s world (names, faces, concrete plans), a definable era seems hopelessly out of reach. Like Certified Copy and its fluid sense of identity, Transit never quite offers you sturdy footing. It means to do to the viewer what war does to those who escape it: untether, disorient, displace.

But no meditation on fluid identity could be quite as disorienting as The Lighthouse. Robert Eggers’ psychological horror, set in old-timey New England, is the sort of film that makes you wonder “How the hell did this get greenlit?” And I mean that in the most adoring possible way. A claustrophobic two-hander between an aging lighthouse keeper (Willem Dafoe) and his short-term recruit (Robert Pattinson), the film cycles through every conceivable relationship the two men might have. Whether working in silence, heaping curses over lobster, harboring paranoid delusions, or guzzling kerosene by the jug, they can’t seem to escape each other’s withering stare—a stare framed, always, in picturesque black and white. At its best, companionship can give safe harbor from a storm. At its worst, it can wring a wickie wode.

3. Capitalism numbs the soul: Parasite, Us, Sorry We Missed You

Filmmaking, like macroeconomics, has a certain built-in time delay—with so many variables between concept and execution, it’s hard to trace any neat causal links. So I don’t know when this particular sentiment started; I only know that it hit 2019 like a third act flash flood. It goes like this: unconstrained capitalism is a soul-numbing force. Many, many, many films orbited this idea. Three of them, premiering in a single 2 month period, examined the human toll that soul-numbing takes.

Filmmaking, like macroeconomics, has a certain built-in time delay—with so many variables between concept and execution, it’s hard to trace any neat causal links. So I don’t know when this particular sentiment started; I only know that it hit 2019 like a third act flash flood. It goes like this: unconstrained capitalism is a soul-numbing force. Many, many, many films orbited this idea. Three of them, premiering in a single 2 month period, examined the human toll that soul-numbing takes.

What can be said about Parasite that hasn’t already been said? Bong Joon Ho’s masterwork of structural engineering has it all, deftly juggling its statuses as festival darling, crowdpleasing thriller, and awards season heavy-hitter—all while maintaining its twisty (and seemingly unspoilable) mystique and a gloriously defiant weird streak. And did I mention that one inch barrier? Despite its near universal appeal, this is a genuinely challenging movie, a parable about the cruel forces that pit have against have-not, scapegoat against scapegoat, in a futile race up a ladder to nowhere. It suggests that by building our successes on the ruin of others, we all become a little bit monstrous.

Us may have taken “monstrous” in a more literal direction, but it shares eerie similarities in the telling. When Jordan Peele’s long-awaited sophomore effort was finally released, I’m not sure audiences knew what to make of it. Unlike Get Out, its plot mechanics don’t lend itself to easy, this-is-a-metaphor-for-that social mappings. Instead, it does what horror does best: it visually conveys an emotional truth which words alone couldn’t cover. Not the why of it all, but the simmering what. Above and below. The dancer and her shadow. The Other, banished to a parasitic half-life, dreaming of the day she can step into the light.

Ken Loach’s characters have dreams, too, though there’s no time for lofty abstraction. In Sorry We Missed You, even your dreams have to cut to the chase. To pay the bills. To pencil in intimacy once a week or two. To take a piss without falling behind schedule. To see the kids, just for a few stress-free minutes, before it’s back to the stale daily grind. With his signature brand of bone-deep social realism, Loach follows the lives of a delivery truck driver and his caregiver wife as they struggle to make ends meet. As stress begets sleeplessness begets missed hours begets a cycle, our protagonists eventually hit a breaking point. “I’m trying my best” one eventually cries, but it never seems to be quite enough. It should be, though. It must be. We ought to demand it.

2. Longing is its own type of beauty: The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Apollo 11, It Must Be Heaven

In a list with no shortage of tenuous connections, this one is the hardest to pinpoint. I’m struggling to put it in words. It isn’t an idea so much as a sensation; a very particular angle of approach. And it has something to do with longing. How certain spaces, when properly framed, seem to call to you even as they push you away. How they carve some entrancing middle ground between attainable and not, instill in you an irrational, pre-emptive nostalgia. It’s no surprise that these films are among the most visually sumptuous of the year. Every still could be a painting. Every painting makes you want.

In a list with no shortage of tenuous connections, this one is the hardest to pinpoint. I’m struggling to put it in words. It isn’t an idea so much as a sensation; a very particular angle of approach. And it has something to do with longing. How certain spaces, when properly framed, seem to call to you even as they push you away. How they carve some entrancing middle ground between attainable and not, instill in you an irrational, pre-emptive nostalgia. It’s no surprise that these films are among the most visually sumptuous of the year. Every still could be a painting. Every painting makes you want.

“You don’t get to hate it unless you love it.” The Last Black Man In San Francisco, Joe Talbot and Jimmie Fails’ meticulously composed love-hate letter to the city I live in, is complicated to write about. On the one hand, I can’t really see it without inserting myself in it: how it gives voice to the wistfulness that blooms on my commute, how it captures some ineffable, uncanny beauty. On the other, my need to insert myself is very much the problem. A rhapsodic mood-piece about gentrification, the black experience in an increasingly white-washed town, and the unique pain of losing the place you call home, the film is achingly specific and decidedly not mine. But there’s something about its specificity that generalizes, envelops everything; the way it dances so deftly between hate and love, exile and connectedness. The way it seems so uninterested in answering its own questions. Like it would rather pause, for a moment, to let us take in the view.

In Apollo 11, what a striking view it is. Our first trip to the moon brought with it no shortage of moral contradictions in its own right. Was it a monument to reckless excess from a nation on the verge of self-destruction, or a glorious sign of unity to a hope-hungry world? Maybe neither, maybe both. The only thing I’m clear on is that it was indescribably, almost painfully beautiful. As a symbol, yes, but also in the literal sense: from the red, fiery thrusters to the chilly dark of space, every moment in Todd Douglas Miller’s found documentary—a triumph of narrative-free editing which deserves an Academy Award in color correction, if not a Nobel Prize—seems flawless, Platonic, pristine.

While some were gazing upwards, a deeper expanse was growing around us. In Elia Suleiman’s It Must Be Heaven, terrestrial living is imbued with its own alien wonder: inherently unknowable and impossibly removed. A marvel of wordless situational humor, the Palestinian/Israeli director’s film bears more resemblance to Jacques Tati than anything I’ve seen this century. Flawlessly shot on location in Palestine, Paris, and New York City, it stands as yet another love-hate letter; this time to a world divided. It reminds us that even in our dividedness, we are fundamentally alike. That even inaccessibility might be a thing that we share.

1. There is transformative power in confronting the past: Honey Boy, Ad Astra, Leaving Neverland

In last year’s list, I saw cinema as a response to trauma—whether an escape, a confession, or an act of defiance. Maybe that was still rattling around in my skull when I sat down in theatres this year. Because for me, in a year jam-packed with fantastic films, the ones that moved me most felt less like storytelling than therapy sessions, working out the damage done by deeply flawed men. Each carried with them a collective exhale; a recognition that, by confronting the past head-on, we might eventually move beyond it.

In last year’s list, I saw cinema as a response to trauma—whether an escape, a confession, or an act of defiance. Maybe that was still rattling around in my skull when I sat down in theatres this year. Because for me, in a year jam-packed with fantastic films, the ones that moved me most felt less like storytelling than therapy sessions, working out the damage done by deeply flawed men. Each carried with them a collective exhale; a recognition that, by confronting the past head-on, we might eventually move beyond it.

Was there any act of testimony more powerful than Dan Reed’s haunting Leaving Neverland? Not only in its profound emotional impact—the heart-wrenching details of sexual abuse, the almost unbearable clarity in Robson and Safechuck’s account—but in the ways it rippled through our collective conscience. If you’d asked about Michael Jackson’s “unsavory” behavior a few years ago, I would have conceded it was likely. So how damning is it that I didn’t feel a thing? Like most everyone in my generation, I’d let jokes and euphemisms diminish the reality of it: the complicated pain, the unresolved guilt, the way rape tears at the seams of a person. By reliving an unimaginably painful past, these survivors gave us new tools for unpacking power and the cult of personality. They’ve changed the way I see the world.

It might seem bizarre to follow a harrowing documentary with a sci-fi epic starring Brad Pitt. But from the moment Ad Astra begins, it’s clear that director James Gray is aiming at much more than a CG spectacle. Instead, he’s interested in unpacking something deep in the psyche. Much like Terence Malick and his sweeping shots of nature, Gray uses the vastness of space to amplify the infinitely refracting whispers of our own inner monologue. The urge to be entirely, hyperbolically alone with one’s thoughts; that insistent need to salvage the past, to find a deeper meaning, that could drive a man to madness or to Neptune’s lifeless rings. It’s a meditation on the extraordinary lengths the male ego will go to avoid taking one small emotional step: to release, to dethaw, to be open to your own pain.

Because real life pain, met with attention and vulnerability, can be mined for something precious. You may have noticed I’m writing this last group out of order. It’s because I can’t think of any better way to end this than with Honey Boy, my favorite film of 2019. I love everything about this movie. I love its audacity: a work of metafictional group therapy, penned by Shia LaBeouf, in which he plays his own abusive father—and doesn’t just play him, but humanizes him, understands him, resists every whiff of self pity. I love its pitch-perfect execution: LaBeouf gives a career-best performance which, in a just world, would win every award (let alone nomination), but the other two Shias (Noah Jupe and Lucas Hedges, here renamed “Otis”) are also uncannily good. I love its tenderness: Alex Somers’ sparse, delicate score; Natasha Braier’s gorgeous use of light and shadow; Alma Har’el’s empathetic direction—so tactile and free-flowing and unabashedly intimate, it recalls another LaBeouf-starring “Honey” film which topped an earlier list. And I love, above all, its commitment to truth: armed with a premise that would have made even the treacliest indulgence feel earned, the film consistently avoids easy or feel-good answers. It encourages us to mourn abuse, yes, absolutely. But it also makes us recognize ourselves in it, inhabit its motive, even laugh at the particular shape that it takes. “The only thing my father gave me that was worth anything,” laments Otis, “was pain. And you’re trying to take it away from me.” No one has any right to take that terrible gift away. But through a fearless commitment to honesty in art, Shia proves that pain is like the fishes and loaves: it can be expounded on, shared, without losing a thing.

Here’s to more miracles in 2020.

Closing Bits, Shameless Plugs

Even at this excessive length, there were a number of equally fantastic films that (largely thanks to the “group-around-a-theme” imperative) I failed to squeeze in: Mati Diop’s hypnotic Atlantics, Ladj Ly’s firecracker Les Miserables, and Rachel Lear’s first-pumping Knock Down The House are among the casualties I regret the most. And though this roundup is marginally more diverse than some in years past, that’s a pathetically low bar to clear. I particularly wish I’d invested more in Chinese cinema, with Shadow, Long Day’s Journey Into Night, and Ash Is Purest White all remaining as blindspots, despite their rave critical reception and relatively easy access. I’ll be honest: when I’m at home or stressed, I find myself resisting Bong’s “one-inch barrier” more often than I’m proud of. In 2020, I plan to be more intentional in overcoming it.

And hey, if you’re still here, the avalanche of content is just beginning! In addition to written reviews here on this site (which I tried to link inline, when appropriate), you can find untold hours of me yammering into a microphone, courtesy of The Spoiler Warning! Podcast episodes for mentioned films include:

- Honey Boy

- The Last Black Man in San Francisco

- Ad Astra

- Parasite

- Us

- Marriage Story

- The Lighthouse

- Queen & Slim

- Paddleton

- The Farewell

- Blackbird

- Midsommar

- Uncut Gems

- Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood

- The Irishman

- Jojo Rabbit

- Joker

- Bonus: Cannes 2019 First Half Recap (For Pain & Glory, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Sorry We Missed You)

-

As usual, I’m violating critical norms by counting festival screenings in the year that I saw them rather than the year of their official US release. This isn’t due to any ulterior motive; it’s simply because it’s too damn complicated to keep track of things any other way. My tally of 121 eligible films excludes most of the classic Letterboxd cheats (some dozen comedy specials, seasons of television, wonderful limited series like Netflix’s Unbelievable), but does include two featurettes I saw in theatres (Gaspar Noe’s 50 minute Lux AEterna, Kanye West’s 31 minute Jesus Is King), as well as a lone two-part documentary (Leaving Neverland). Of that 121 there were 9 I saw twice, making a total of 130 “2019 film viewing experiences.” I spent most of my downtime watching older stuff this year, which means the vast majority of contemporary releases were seen on a big screen: 56 (43%) were in traditional theatres and 48 (37%) were festival screenings, with only 13 (10%) at home and another 13 (10%) on planes. This Best Of list follows similar trends, and generally debunks the Sappy Plane-Goggles theory of year-end-list-making: 42% theatrical, 33% festival, 12.5% home, 12.5% planes—biased slightly by the number of theatrical rewatches of festival films on this list (ignore duplicates, and the festival category jumps to a whopping 40% in both tallies). That heavy emphasis on festival releases allowed for an unusually strong selection bias: I genuinely liked-to-loved the majority of things I saw this year. 21% met the high bar of “Great”, 40% were “Good”, 27% were at least “Pretty OK”, and only 12% were downright “Bad”. So, even at a bloated 32 films, rest assured that this is not merely a list of everything I strongly recommend: there are at least 40 other titles that didn’t make the cut. I’ll say it again. This was a very good year.↩

-

Some other films I’d recommend without reservation: 1917, A Hidden Life, Atlantics, Avengers: Endgame, Bacurau, Between Two Ferns: The Movie, Blinded By The Light, Booksmart, Bull, Fighting with My Family, Ford v Ferrari, Hail Satan?, Happy Death Day 2 U, High Flying Bird, Knives Out, Knock Down the House, Les Miserables, Lux AEterna, Matthias & Maxime, Mickey and the Bear, Proxima, Ready or Not, Shazam!, Spider-Man: Far from Home, Sword of Trust, Teen Spirit, The Art of Self-Defense, The Biggest Little Farm, The Death of Dick Long, The Lego Movie 2, The Nightingale, The Peanut Butter Falcon, The Report, Tigers Are Not Afraid, True History of the Kelly Gang, Wild Rose.↩

-

I also can’t help but compare this to another film, also starring Moises Arias: 2013’s The Kings of Summer. Like Monos, it also centered around a small group of kids who form a “society” of sorts out in nature. But where Summer suggested something joyous about childhood imagination and escape, Monos demonstrates how easily those things might be perverted.↩

-

On more than one occasion, I’ve tried to describe my love of this movie only to realize I sound exactly like a character in Seinfeld praising Rochelle, Rochelle.↩