A loopy walk through the 2016-2018 cinematic landscape and the societal stages of grief it mirrors, as filtered through the music of Phil Elverum and Kimya Dawson

In this piece, I’m going to reference a bunch of recent films, mildly spoiling several in the process: Manchester By The Sea, A Ghost Story, BlacKkKlansman, Blindspotting, Hannah Gadsby’s “Nanette”1. Odds are, there are at least some of these you haven’t seen. I’ll do my best to write this in a way that doesn’t ruin your future enjoyment, and doesn’t require prior knowledge to follow along. I’ll also be blurring quite a few lines in the process—real-life grief and fictional tragedy, actors and the characters they play—in a manner that would seem calloused if taken literally. Take this, instead, in the spirit that I write; as a personal rumination on blurry things.

Intro

So thank you Geneviève, cause you take what is in your head

And you make things that are so beautiful and share them with your friends

We all become important when we realize our goal

Should be to figure out our role within the context of the whole

And yeah rock n’ roll is fun, but if you ever hear someone

Say “You are huge,” look at the moon, look at the stars, look at the sun

Look at the ocean and the desert and the mountains and the sky

Say “I am just a speck of dust inside a giant’s eye”

– Kimya Dawson, “I Like Giants” (2006)The feeling of being in the mountains

Is a dream of self-negation[…]

But actual negation

When your person is gone

And the bedroom door yawns

There is nothing to learn

Her absence is a scream

Saying nothing

– Mount Eerie, “Emptiness Pt. 2” (2017)I sing to you

I sing to you, Geneviève

I sing to you

You don’t exist.

I sing to you, though.

– Mount Eerie, “Tintin in Tibet” (2018)

With an hour to kill before the AJJ concert, my girlfriend and I put on an episode of Variety’s “Actors on Actors.” In it, two actors sit alone in a room and quiz one another on their artistic process; the premise being that an inside baseball conversation might probe at deeper truths than a typical interview. Example topics: How did you channel that specific emotion? What attracted you to this particular director? How do you balance instinct and pliability?

This particular conversation was between Natalie Portman and Michelle Williams, there to promote Jackie and Manchester By The Sea, respectively. Both had portrayed women upended by tragedy, so their conversation naturally turned to grief. Portman discussed the confines of historical fiction on a technical level, where her need to be literally accurate felt at odds with her desire to be emotionally honest in her mourning. Williams hit a more personal note, wondering how anyone could genuinely embody grief without letting it destroy them. The role had required her to “put on” grief during her daily commute to the New England coast, to inhabit and discard it repeatedly, at will. As she discussed the toll that balancing act exerted, I couldn’t help but remember another public tragedy—the passing of her child’s father, Heath Ledger—and the voyeuristic artist-consumed-by-a-role narrative that surrounded it.

Later, at the bar between openers, I revisited my review of Manchester By The Sea—something I’d felt reasonably proud of at the time of writing. With two years remove, it felt clumsy. Some bits still rang true: the banality of tragedy, the notion of an “apprenticeship in grief.” But my read of the film had been fundamentally lopsided; I’d managed to spend paragraphs waxing poetic about my own insecurities and Casey Affleck’s brooding, without granting Williams a single word. All that heaviness she’d confessed to, of a grief so lived-in it clung to the evening commute…and for what? A footnote? It’s not that I hadn’t noticed her performance. Quite the opposite. Come Oscar season I’d be singing her praises. It’s that I couldn’t find an interesting way of describing the sadness she possessed. Affleck’s inward destruction felt more profound, more “artistic,” than Williams’ outward agony. This was the same year that I’d heap praises on Louis C.K.’s Horace and Pete for its similarly understated treatment of flawed, haunted men. Google either name today and a pattern might emerge.

I rejoined the fray for the second opener, Kimya Dawson, a former “anti-folk” artist best known as one half of The Moldy Peaches. I hadn’t followed her career since Juno, and though I’d been a fan my expectations were low. Hadn’t that whole scene been a flash in the pan? It stripped away pretense, sure, but what substantive replacement had it proposed? Off-key ukuleles and ditties about friendship? In hindsight, it felt extremely mid-2000’s. It felt twee. My suspicions seemed all but confirmed when she walked out to the stage, armed with tiny guitar and stool, and asked the crowd to sit down. After a bit of scattered, awkward laughter, they complied; some four hundred hipsters sitting criss-cross-apple-sauce on a beer-sticky floor lit by disco ball sparkles. Preemptively, I cringed.

Then she started to play. Kimya opened with her recent foray into children’s music, strumming silly songs about farts and the alphabet to a game (if mildly confused) audience. Slowly, though, a progression emerged. Nursery rhymes gave way to thinly-veiled allegories, gave way to labyrinthine personal stories, gave way to perfectly-articulated insecurities. It wasn’t cute for cuteness’ sake; it was sharpened poetry, using childlike directness to disarm and surprise. It was actually, come to think of it, pretty damn clever. Then she performed a song that was neither cute nor clever: a rumination on childhood loss, grappling with the early passing of a friend. I’d encourage you to stop reading and listen to this one for yourself.

Quarter century later it’s still hard to take

But with every red taillight I scream out your name

I say “Daniel, Daniel, Daniel,

Baby Boy, Baby Boy, Baby Boy”

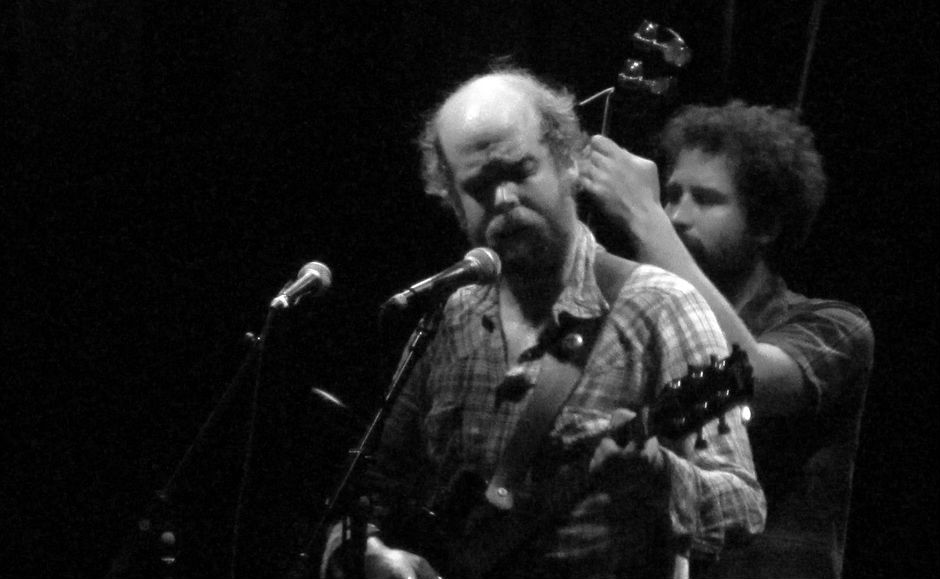

After the final “baby boy” ended, you could have heard a pin drop in that crowded auditorium. It floored me. And in its overwhelming directness, it brought me back to a performance I’d seen earlier this February: Phil Elverum, i.e., Mount Eerie. He too had brought an audience to tears using nothing but hushed vocals and plucked nylon strings. But his was a more adult pain, “catatonic and raw,” confronting the recent loss of his wife, Geneviève Castrée. Or, rather, her death: “loss” seems like a euphemism he would eschew for sturdier diction. Over the course of an hour he dissected his grief with uncompromising frankness. Sometimes this turned inward, chronicling his sudden loss of normalcy (“I now wield the power to transform a grocery store aisle into a canyon of pity and confusion”). Others it turned outward, addressing her directly (“The second dead body I ever saw was you, Geneviève, when I watched you turn from alive to dead right here in our house”). But that evening was always about pain, focused and clear, a communion of grief among a handful of strangers. A group which, incidentally, had counted Michelle Williams among their number—sitting behind the merch table, visibly moved.

Dawson’s next piece was an act of political protest, redirecting her anguish from personal pain to social upheaval:

Hands up, don’t shoot, I can’t breathe

Black lives matter, no justice no peace

I know that we can overcome because I had a dream

A dream we tore this racist broken system apart at the seams

As the crowd lifted in that chorus, I marveled at how much her show seemed to mimic an evolution of art in general. That if navel-gazing art about art had defined my youth, and raw directness (childish or adult) the past few years, the new normal was an earnest contradiction. A tone at odds with its message. A smile betrayed by its tears. Peppy singalongs about police brutality, fiery exhortations with a cotton candy sheen. I thought about Spike Lee, and his insistence on pulling the rug out from his own narrative; about Hannah Gadsby, and her refusal to release the tension she’d instilled. And it seemed to me, then, that we were in the middle of an inflection point, of some new collective stage of grief. Not from denial to anger to an eventual acceptance, but from artifice to authenticity to a dissonance that couldn’t, shouldn’t, resolve.

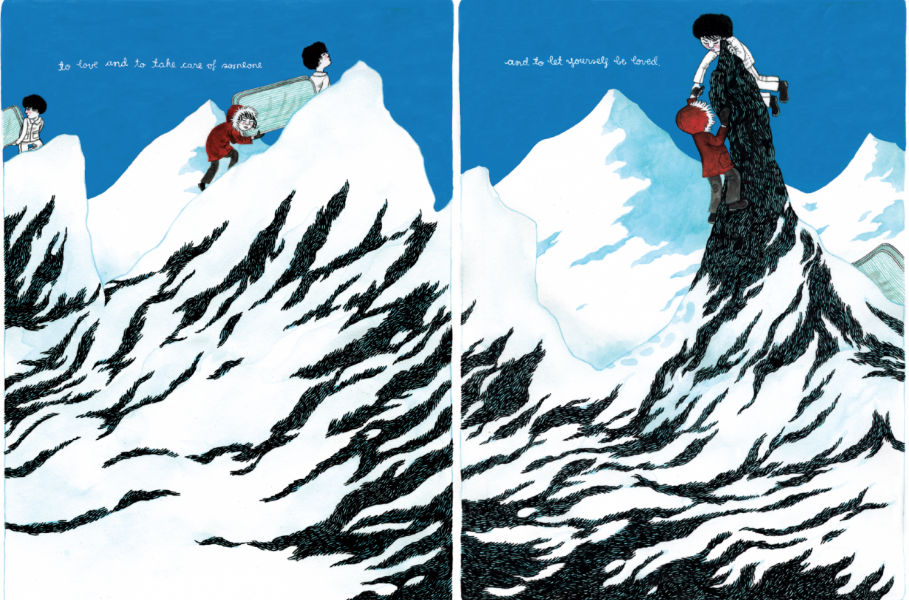

While Kimya strummed through the rest of her setlist, I felt all of these pieces begin to coalesce. In film, in music, in the culture writ large. I saw a through-line of tangled heartaches for which poetry offered no respite, an exodus of storytellers disillusioned with fiction but unsure of any alternate promised land. She sang about personal demons and the need to be valued—to be reminded of her own strength, her power, her lovability. She sang about friendship, contentedness, the beauty of little things. And she sang about a giant, standing on the edge of a cliff, wishing she were dead; about negating ourselves in service to some larger whole. A story which, I’d later learn, was given to her by a dear friend: cartoonist, musician, and late wife of Phil, Geneviève Castrée. The same voice which led one artist to such metaphorical heights would inspire another to forego metaphor entirely; Dawson’s dream of self negation versus Elverum’s gasping actualization, a giant rebuffed by an echo. Was there a unified message in this seeming incongruity? Or was that friction, itself, the point?

Scaling down: the quest for authenticity

All girls feel too big sometimes, regardless of their size

– Kimya Dawson, “I Like Giants” (2006)I turned my head, I closed my eyes, I felt my size

– The Microphones, “I Felt My Size” (2001)

To help explain how my perception of art is changing, it’s useful to go back to the first medium that really gripped me. So while this essay is primarily about my current obsession, film, it’s going to take a detour into my former one: mid-90’s to mid-2000’s indie folk. (I know, I know. I hate the label too).

At the time I was musically coming of age, folk-adjacent movements were a dime a dozen. There were the largely meaningless umbrella headings of “alt country” or “indie folk,” connoting anything from the hushed vocals of Iron and Wine to the stomp-and-howl fire of Okkervil River, from the low-fi poetry of The Mountain Goats to the rich orchestral flourishes of Sufjan Stevens. Within that fold was the revivalist genre of “freak folk,” helmed by rising figures like Joanna Newsom and Devendra Banhart. An homage to the psychedelic folk of the 60’s, theirs encouraged a more freewheeling style of expression: chants, whistles, Appalachian yelps. AJJ (then “Andrew Jackson Jihad”) were beginning to explore a different sort of chaos with their “folk punk” sound, brimming with manic, burn-it-down freneticism. Conor Oberst was composing delicate “emo folk” as Bright Eyes; David Thomas Broughton a haunting, layered “avant-folk”; the Decemberists a jaunty “baroque folk.” And then there was “anti-folk.”

None of this was set in stone, of course—these hip delineations were simply how I categorized the world at 15, back when enjoyment meant fandom and fandom meant, essentially, an enormous filing cabinet of intelligent-sounding labels. But from what I could gather, and what the name implied, anti-folk was inherently reactionary: much like punk’s relationship to 70’s stadium rock, it defined itself primarily by what it wasn’t. Popularized by The Moldy Peaches in the late 90’s—and catapulted into the Zeitgeist with the release of 2005’s Juno—it seemed to be a rebellion against overseriousness, against even a whiff of pretense. The music was simple, arguably to a fault: a ukulele noodling over two or three chords, tune…adjacent?…vocals, and kidspeak diction:

Here is the church and here is the steeple

We sure are cute for two ugly people

I don’t see what anyone can see

In anyone else but you

– The Moldy Peaches, “Anyone Else But You”

But where, exactly, had this rebellion come from? After all, the genre it stemmed from could hardly be called ostentatious: while the mid-2000’s would usher in more radio-friendly era, the indie scene of yore had minimalism in its blood. Its most mythic figures were often solo acts, performing under cryptic monikers and foregoing the trappings of mainstream appeal.

I counted Phil Elverum (The Microphones, Mount Eerie) among these figures, his The Glow Pt. 2 having reached a cultlike status in my corner of the world. Finding a Microphones LP in a used record store was the stuff of legend, akin to finding a Banksy mural in your neighborhood alleyway. Crafting layered soundscapes out of feedback whirring and plucked strings, his songs were simultaneously oblique and direct, with lyrics that rang as mystic confessions:

From high above you

I saw your earthling body wrapped in wool

The glow surrounds you

And when you breathed in, I felt the pull

– The Microphones, “The Pull”

If Phil had a soft spot for the occasional high concept, his peers intentionally eschewed them. Bill Callahan (Smog), for his part, was perfecting a much more traditional country sound—his brilliance was his brevity, wielded like a knife. Jaw-dropping beauty was found as often in the gaps as in the lyrics themselves, in the undercurrent of loneliness and sorrow:

Most of my fantasies are of making someone else come

Most of my fantasies are of to be of use

To be of some hard, simple, undeniable use

– Smog, “To Be Of Use”

Meanwhile, Jason Molina (Songs: Ohia, Magnolia Electric Co.) was navigating a more tortured route, pairing trembling wails with sparse accompaniment: a minor-key guitar riff, a whispered female vocal, or sometimes nothing but rickety percussion and desert wind. His was a music that lodged in your skull; that gnawed away at you, haunted:

Put no limits on the words

Simply to live, that is my plan

In a city that breaks us

I will say nothing

– Songs: Ohia, “No Limits On The Words”

Foretelling it all was Will Oldham (Palace Brothers, Palace Music, Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy), whose rugged aesthetic and allergy to interviews cast him in an almost monastic light. With a warbling voice, ramshackle arrangements, and stories that trafficked in the genre’s more depraved traditions, he was about as far from modern “rock star” as a performer could be. If anything his music felt like a ghost of Americana past: menacing and tender, mournful and hardened. Stripped away to its barest essentials, everything suddenly mattered. When his voice cracked, you felt a lifetime of heartbreak; when he barked like a dog, he barked cold gospel truth. His was a darkness which could revitalize Johnny Cash; a gnarled, prickly something which would attract filmmakers as diverse as John Sayles, Harmony Korine, Kelly Reichardt, and eventually David Lowery. But more on that later.

There is absence, there is lack

There are wolves here abound

You will miss me

When I turn around

When you have no one

No one can hurt you

– Palace Brothers, “You Will Miss Me When I Burn”

Suffice it to say, there was no shortage of simplicity. Certainly not in the music: the ghastly thumps of Oldham’s “Come a Little Dog” or Molina’s “Lightning Risked It All” make Dawson’s work sound damn near overproduced. Nor in the lyrics themselves: if these artists had anything in common, it was a knack for the understated, the terrifying beauty of the everyday word. No, what anti-folk rebelled against had less to do with art than with the aura that surrounded it—with me, in other words, and all my hyperbolic praise. It argued that folk didn’t need to devastate. It didn’t need to be shrouded in mystery, wrapped in generational darkness, “gorgeously” anything. Folk could be two people professing feelings with no agenda, not even a meta-agenda of appearing confessional, saying no more or less than what was meant. All girls feel too big sometimes. We sure are cute for two ugly people. It’s not as if I don’t like you, it just makes me sad. I miss you. I’m in love with how you feel. Why can’t you forgive me?

You’ll notice a lot of first-person pronouns there. Without a pretense to hide behind, the self inevitably took center stage. And what did the self of an artist worry about? Ephemerality. Its place in the universe. Its place, more specifically, in the musical landscape: was its contribution “huge,” or was it “a speck of dust”? Did any of this ultimately matter? Fellow anti-folkster Jeffrey Lewis put a finer point on it with his breathless epic Williamsburg Will Oldham Horror, chronicling a fantasy day-in-the-life of a struggling artist whose chance encounter with Will Oldham sends him down an existential spiral:

This quest for greatness, or at least hipness

Just a scam and too much trouble

But then, what makes one human being worthy of an easy ride?

Born to be a natural artist you love or hate but can’t deny

While us minions in our millions tumble into history’s chasm

We might have a couple of laughs but we’re still wastes of protoplasm

As art struggled to let go of outward posturing, it seemed the only direction left to reach for was inward. Pierce its own bubble, critique its own value. To my adolescent sensibilities, there could be no greater meaning than this: to self-analyze, to willfully implode. Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman had blown my mind with Adaptation (2002), the film about the impossibility of making a film about a book about orchids—nature, blissfully apathetic, having created something more stirring than all layers of human invention. A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius (2000) used the memoir format to prove the impossibility of memoirs, a sort of Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem for honesty in storytelling. And David Foster Wallace’s “Good Old Neon” (2004) would remain a favorite of mine for years: an examination of the toxic reductiveness of overthinking, and—in a tour de force ending—the mental gymnastics required to convert a human being into a character. That Wallace himself chose to end his life only added to its allure—though I’d never have admitted it at the time. This was supposed to be about about rejecting mythologies, not constructing new ones.

The dam would eventually break in the music scene, and all that competing obsessiveness would relax into something more straightforward, loose. Molina and Oberst would both evolve from their tortured solo aesthetics into a more joyous, full-band sound. Dawson would cultivate a more constructive lightness, defined by advocacy and positive thought. And while Elverum would maintain a bit of that sartorial buffer, the whimsy and joy grew easier to spot. One of my favorites from this era, “Voice in the Headphones,” might also be the most straightforward of his career; a simple ode to the power of music.

Oldham, for his part, would soon invert that gloomy “hipness” Lewis had skewered, moving from tranquil (2006’s Then The Letting Go) to hopeful (2007’s Lie Down In The Light) to downright giddy (2008’s Beware!), and confounding fans in the process. When I finally saw him in 2010, the former Jandek-esque prophet was dancing in denim overalls at an outdoor bluegrass festival, ear-to-ear and banjo twanging. The next time I’d encounter him would be in the soundtrack of a Disney movie, David Lowery’s remake of Pete’s Dragon. And hearing him croon about dragons in magical forests would feel right somehow. Like something he’d been working at all along. The trajectory from inner darkness to childlike wonder, it turns out, is a short, straight line.

The mad that we feel: childlike simplicity

What protects us as kids slowly makes us insane

So I’m trying to dismantle barricades

Brick by brick in an attempt to set free my brain

– Kimya Dawson, “Daniel (Baby Boy)” (2014)Hank: Maybe that’s just something the brain invents to survive.

Manny: Yeah. Like maybe your brain invented me to distract you from the fact that eventually your eyes are gonna stop blinking and your mouth will stop chewing and your blood will stop pumping and then you’re gonna shit yourself. And that’s it.

– Swiss Army Man (2016)

Since at least 2010, I’ve put together an annual Best Films Of The Year list. They’ve tended to be disjointed and, like any ranking, inherently personal. But in my 2016 recap, I wanted to try something different. Staring at my 10 or 15 chosen titles, I couldn’t shake the feeling that they were collectively telling a story. Or rather, that they were attempts at answering similar questions: fragments of some national meditation or societal self-talk, a people reiterating basic truths for fear that they might slip.

Recently single and digging for profundity in just about anything, I was, of course, projecting. But I wasn’t the only one grasping for meaning: many in my generation, who had come of voting age during the first Obama election, were experiencing our first real taste of political despair. That fall of 2016 was, we’d hoped, the crest of a particularly ugly wave; of bitterness, xenophobia, fearmongering, bigotry. That wave had always existed to those who were paying attention, or who (be it by skin color, parentage, sexuality, religion) weren’t afforded the luxury of ignorance. But to those of us who were a bit more naive, more starry-eyed about national politics, it roared from a depth we hadn’t anticipated. It shattered something fundamental. Things I’d taken as bedrock truths, even formed an identity around—the power of empathy to change minds, the ability to reach consensus through good faith conversation, the inherent goodness of the majority if only it could be properly harnessed—had proven absurdly insufficient. Words failed, dramatically, in the face of whatever this was. And what was left in its wake wasn’t that old, Bush-era cynicism. It was confusion, shock, a prodding at the most basic of questions. Are we fundamentally good? Can we genuinely love? Is there any value left in honest conversation? Who, exactly, are we trying to be?

That yearning pulsed through the stories we told. Largely absent was the typical “clever” fare—the antihero we root for against our better judgement, the brash-talking cynic who triumphs over a bland status quo. Instead I saw a purity of feeling, often achingly direct; a collection of capital T Themes being mainlined into our collective psyche. All too often, our culture pits honesty against subtlety: when a work lays its messages bare, it’s seen as obvious, artless. So it’s fitting that many of the films that hit me hardest had been framed around explaining things to children—providing cover for a sincerity that might otherwise be rejected.

Some of these were literal children’s movies. Zootopia used animals to paint a dual picture of American society: here is how it ought to be, free of short-sighted divisions, and here is how it is, rooted in xenophobic fear. So did Pete’s Dragon confront grief and familial loss; so would Coco the need to anchor our identities in sturdier soil. Truths so simple, so obvious, yet capable of reducing a reviewer to tears. When Won’t You Be My Neighbor hit theatres this year, it finally rendered all of this subtext as text, showing how lessons ostensibly meant for children often ripple through society at large. It posits that children’s entertainment can serve as a form of therapy; that unadorned truths can pierce even a lifetime of hardness. Like Kimya to her Daniel, we dismantle barricades in the presence of Fred’s tiger, and there’s some catharsis in the sheer simplicity of his response. Rogers’ words to a 1969 Senate committee resound, today, like a political exhortation:

What do you do with the mad that you feel

When you feel so mad you could bite?

When the whole wide world seems oh, so wrong…

And nothing you do seems very right?

– Fred Rogers, featured in Won’t You Be My Neighbor

Other films, more explicitly aimed at adults, used a teacher/student framing device to present hard truths in a similarly childlike way. In Room, a young mother (“Ma”) teaches her son to survive via an ad hoc set of rules and rewards, her optimistic fictions barely veiling the turmoil within. And Swiss Army Man would take a similar concept to bizarre extremes, letting emotionally-stunted adults play the role of both student and teacher; crafting storybook lessons to navigate the awkward vagaries of 21st century life.

Perhaps most striking, though, was Manchester By The Sea, where the flaws of the teacher comprised their own lesson. Casey Affleck’s Lee knows more about suffering than just about anyone, but constructively coping isn’t a luxury he’s been afforded. So when his nephew, Patrick, loses his father, he can’t find much of value to say—neither platitudes like Rogers’ nor coping fantasies like Ma’s. Knowledge is imparted instead by osmosis; by the raw outbursts he allows his nephew to see. Here the needs are, interestingly, inverted: Patrick isn’t a wide-eyed child grasping for answers, he’s a teen who believes himself to be coping just fine. Lee is tasked with imparting a messier lesson—to let Patrick know that he isn’t fine, that none of us are. That grief was never meant to be easy or quick. As we watch Lee himself mourn, destructively, through Patrick’s eyes, empty reassurances thaw into something harder to name. It isn’t okay. It was never supposed to be.

This pattern would continue—is continuing—on plenty of fronts. Coming of age stories may be the most common vehicle for unsubtle communication, with many recent films featuring a seminal third act conversation between a young protagonist and an adult mentor, speaking with a candor they’d otherwise avoid. And sometimes the proxy isn’t a child at all, but an onscreen audience—free of all context and thereby a similarly blank slate2. Regardless of the recipient, the outcome is the same: the unadorned expression of shared emotional truth. We crave these lessons not because they are new or surprising, but precisely because they are already known to us. Maybe by reiterating those answers that hide in plain sight, we can shake loose the dread that obscures them.

Words fail: unfiltered anguish

I am a container of stories about you

And I bring you up repeatedly, uninvited to

– Mount Eerie, “My Chasm” (2017)Patrick: You can’t make small talk like every other grown-up in the world?

Lee: No.

– Manchester By The Sea (2016)

But answers are not always readily available. And narratives, even simple or childlike, can’t help but fill in the gaps—tilting earnest dialogue into rhetorical flights, imbuing silence with unearned profundity. When even understatement appears to be a brand or meta-statement, when the dialogue utterer can’t help but see the critic behind the camera, how can hard truths be authentically preserved?

A hunger for intimacy has always existed: what was all that tortured folk for, after all, if not to give some window into raw emotion? We’ve always yearned for the howling, the blood; we want to hear poetry borne of pain, but we also want the mic left on while the poet gets up from his chair. Yet in this lopsided post-election era, where all our accumulated words are dwarfed by baser forces, that hunger feels more manic, somehow. Anger, obsession, depression, hope—we’ve seen these torn apart and manipulated, reworked to sell products. We’ve become allergic to performative authenticity: even the act of crafting seems to dampen the blow. We gravitate, instead, towards a pain so natural—so overwhelming—it drowns out the craft.

My first real experience with this phenomenon came a few years prior in the music world. In my brusque rundown of the aughts’ indie scene, I left off a name that proved tough to pin down: Mark Kozelek. As frontman of the Red House Painters in the 90’s, he channeled a shimmering, downbeat sort of beauty. His was a mournfulness you could swim in. At the turn of the century he stripped down and went solo, aiming for a gentler, singer-songwriter ethos—a sound which he’d expand (under the moniker of Sun Kil Moon) into an earthy Americana. The sorrow was there, of course, but it took on a lush, romantic hue. Over the years, though, the hue started to shift. His songwriting would become increasingly more blunt, verbose, culminating in the release of 2014’s Benji.

Carissa was thirty-five

You don’t just raise two kids, take out your trash and die.

In the opening track, “Carissa,” Mark mourns the unexpected death of his second cousin. But rather than wrap it in poetry, he describes the event in near stream-of-consciousness detail: phone calls, travel plans, family histories. Rising to a chorus, he declares—with Will Oldham’s backing—the need “to find a deeper meaning in this senseless tragedy.” From there, the album dives headlong into mortality; not via abstract fictions, but the real deaths of people with names: the schoolchildren lost in the Sandy Hook massacre, an uncle lost in a fire, a childhood friend killed in an accident, and always, just below the surface, Carissa. What little artifice there had been (partitions between chorus and verse, discernible melody) seemed to erode as the album progressed: this was a man openly grieving, tearing down barricades between feeling and art.

Benji was as close a touchstone as I could find to Phil Elverum’s monumental A Crow Looked At Me. Recorded just months after his wife’s passing in the summer of 2016, it documents the mourning process in unbearable detail. I wrote a bit up top about its beauty and frankness. What I haven’t discussed, yet, is its daring refusal toward sentiment or closure. There is no wistful reflection to be found in Phil’s grieving, no light-at-the-end-of-the-tunnel upswing. Even Mark’s quiet impulse to “find a deeper meaning” is absent, here. In his haunting opening lines, he instead denounces even the possibility of resolution:

Death is real

Someone’s there and then they’re not

And it’s not for singing about

It’s not for making into art

When real death enters the house, all poetry is dumb

When I walk into the room where you were

And look into the emptiness instead

All fails

My knees fail

My brain fails

Words fail

“It’s dumb,” he concludes, “and I don’t want to learn anything from this.” He proceeds to make good on that commitment, refusing to wrap his pain in a conceptual bow. On death as a natural counter to life: “I reject nature, I disagree.” On the philosophy of his earlier art: “Conceptual emptiness was cool to talk about, back before I knew my way around these hospitals.” When confronted with a reminder of Geneviève: “Now I can only see you on the fridge in lifeless pictures.” When pondering the symbolism of a flower: “What could anything mean in this crushing absurdity?” There is no Candle In The Wind, here, no metaphorical living-on. He sings, instead, of “dried out, bloody, end-of-life tissues,” of “throwing out [her] underwear”; the banal realities of death standing as their own, unedited thing. If there’s any acknowledgment of universality—that grief might generalize beyond Elverum’s walls—it’s found in the final track. Here, like so many of us, he sees his sorrow mingle with post-election malaise:

Sweet kid, what is this world we’re giving you?

Smoldering and fascist with no mother?

One might imagine this vacuum of sentiment would make for an asphyxiating experience, but far from it: the album is a complex, emotional masterpiece. On first listen the sadness may have deafening; but as I grew more accustomed, more (is there any way to admit this?) numb to that primary emotion, others were amplified. Some seemed to mimic grief itself: bewilderment, release, contradictory warmth, inexplicable calm. Others mimicked precisely nothing, and remain elusive even as I write. It’s a work at once overwhelming and slippery, revealing different aspects of itself with each new listen. By eschewing one or two layers of authorial “meaning”, it appears Elverum was making room for something even deeper and more expressive: a grief preserved rather than a grief crafted, living on as its own multifaceted art3.

While Phil was recording his stages of grief, Kenneth Lonergan was exploring two different strains. Lee’s “teaching” of grief in Manchester By The Sea has already been discussed, guiding his nephew through the highs and lows of familial loss. What I haven’t addressed is Lee’s reaction to his own trauma—the terrible history he shares with his ex-wife Randi (Michelle Williams), undergirding much of the film. Where Patrick’s loss can bear scrutiny, even dark comedy, Lee’s loss—the unexpected tragedy that tore his family apart—remains largely unutterable. Why voice it, when there’s nothing to learn? He instead directs his pain inward, a container of stories that will never unseal. Randi, for her part, isn’t even granted an onscreen silence: but for a few searing emotional outbursts, her grieving process is left entirely to our imagination. And when we, the audience, are finally privy to their shared memory, there is no redemption in sight: a third act conversation between Affleck and Williams provides none of the relief we’ve been conditioned to expect. Instead it’s fragmented, haunted—a scream of absence, saying nothing.

Others would examine this haunting in more literal ways4. In A Ghost Story, Casey Affleck returns to an even more reclusive state of sorrow. Here he is not the bereaved survivor left to mourn alone, but the voiceless object of mourning itself—a literal ghost, behind white sheet and eye-holes, doomed to watch the world’s inevitable forgetting. Neither he nor his wife (Rooney Mara) are even granted names: death is the only substance, here, all else is translucent. When his sudden passing leaves Mara paralyzed and alone, we long for even the clarity of a Lee-style outburst. Instead there is only numb routine. We watch her in silence from across the room: collapsed on the kitchen floor, soaking a bedroom pillow, doing chores for no one. For four unbroken minutes, we watch her eat an entire pie, hunger giving way to desperation giving way to a violent need to feel. There’s no resolution to their story. We’re granted no closure. Mara leaves, eventually, and Affleck’s nameless ghost remains, tethered to the plot of land as it continues without him. Buildings are torn down and erected. Tenants come and go. In one of the only moments of sustained dialogue in the film, Will Oldham appears as a mysterious partygoer. Gone is the lightness that propelled him across the stage; gone too any hint of childlike joy. He instead gives a lengthy, depressing speech about the end of universe, prognosticating at no one in particular with what Wallace might call “that special intensity that comes after about the fourth beer.”

Oldham muses about the impermanence of all things, artistic or otherwise—how despite all striving and noble intention, everything we create will eventually dissipate. Entropy will always win. All symphonies will go unheard; all books will go unread. “Everything that ever made you feel good or stand up tall…it’ll all go.” Or, as Jeffrey Lewis once put it to him, “We might have a couple laughs, but we’re still wastes of protoplasm.” In another film, or another era, this might come across as David Lowery’s clumsy attempt at profundity—some self-satisfied commentary about the futility of art itself. Here it feels jarring, intentionally deflated. The heat death of the universe, the ethereal nature of art? It only amounts to conceptual emptiness. Real death has entered the house, heavy and sheet-clad, and all lofty hypotheticals now feel utterly besides the point. Feel dumb. No, the truth isn’t found in some sermon on endgames, it’s found in the gasping here and now: a longing between the walls which no theory can account for and no moral can sanctify.

This tension: authentic contradiction

Open your fucking eyes now and look, and see.

You might think you know what’s happening,

But you don’t feel it like we do

To feel it it has to be you, cut you

But you don’t know what the cut do

You all reflex, but when reflux bleeds the gut

Then you see the faces

Leave the vases

…

I am both pictures!

See both pictures!

– Collin, Blindspotting (2018)And this tension, it’s yours. I am not helping you anymore. You need to learn what this feels like.

– Hannah Gadsby, Nannette (2018)

There’s a purity in much of what I’ve covered here: unfiltered outbursts, deafening silence. While they don’t offer conclusions in the traditional sense, they come with a clarity of feeling that’s nearly as satisfying. Clean, unmuddied grief often serves as its own answer.

Real world grief, however, is rarely so elegant. And guilt-free pain is only the exception that proves the rule. All too often, our hurt is tangled in something uglier, more self-serving. For every spurned lover seeking a second chance, there’s another whose agency is being actively undermined; behind every tragedy in search of a villain lies a symmetric tragedy about the depths to which one can fall. We mistake narcissism for nuance; we perform our trauma for social capital. While we mourn the rise of overt bigotry into politics, a quiet voice reminds us that it has always been present—that our flimsy shock is, if anything, a primary contributor to its persistence. We decry abuses of power and rally for change, till those we’ve rallied behind are powerful enough to fail us. We’ve seen our lamentations amplified to drown out other voices; watched our fears weaponized, laser-focused and exploited. We’ve learned that empathy can fuel inertia just as easily as its absence fuels backwards motion. The more we listen, it seems, the more complicated our allegiances become. And as the year progresses—from Kaepernick to Kavanaugh—that need to listen has only become more urgent.

By contrast, there’s a whiff of one-sidedness to most of the fictions I’ve offered so far. Consider, one last time, Manchester By The Sea. By zeroing in on the pain absorbed by our protagonist, I’ve turned a blind eye to the hurt he radiates outward. Because behind the complex antihero narrative lives a complementary truth; that Lee was not the only casualty of his temper. That Randi, left to suffer in isolation, may well trace a more meaningful arc. Despite enduring the same hell, she did not crawl inward: she fell to Lee’s depths and climbed up alone, even to the point of impossible forgiveness. She, in a broader sense, is the film’s silent hero—and Lee a frequent source of her pain. It’s difficult not to let current events further color this picture. On one side is Michelle Williams, sufferer of both public losses and private injustice—recipient of Weinstein’s unwanted advances, leading two recent films mired by the behavior of abusive male costars. Rather than retreat, she has come back swinging: a vocal advocate for equal pay in Hollywood, Williams also walked this year’s red carpet with #MeToo founder Tarana Burke. On the other side is Affleck, facing credible accusations of sexual harassment. Still quietly equivocating, still clutching that Oscar.

Broader considerations complicate our stories, particularly where gender roles are concerned. Looking at many of the films I’ve heaped praise on, it’s hard not to see an unflattering dual: the woman-as-object to our unrequited lover, the abusive fruits of our “brave” vulnerability. (Some, to their credit, welcome this criticism: see The Big Sick and Swiss Army Man5). And going down the list of musicians I’ve idolized, I see a pattern which (at its most generous) rhymes: Oldham, Callahan, Molina, Kozelek—all brilliant, brooding, white, male. Each with a handful of songs that strike me as deeply uncomfortable under a modern lens—stories of rage, obsession, of a love and violence inextricably entwined. So too with Charlie Kaufman and the protagonists made in his image, whose neuroticisms so often leave emotional abuses in their wake. Much more so with David Foster Wallace and his real-life harassment of Mary Karr. The list, I am sure, goes depressingly on6.

Early in his career, Oldham offered a simple theory: “when you have no one, no one can hurt you.” But there are more ramifications of a man being an island. When you have no one, no one can help you. When you have no one, no one can teach you. When you have no one, no one can stop you. And if we are in need of anything, in 2018, it’s some collective form of balance. A broader social awareness, to check our baser impulses and widen our blinders, before we self destruct.

Perhaps the most elegant formulation of this need came in Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette, the self-fashioned comedy special about quitting comedy. From the moment it begins, her set is an evisceration of the struggling artist mythos—as fueled by fellow comedians like Louis C.K.—and of single-perspective narrative in general. But hers is a work argued primarily via contradiction: an exercise in building, then demolishing, structurally viable points of view.

After priming the audience with a self-deprecating joke, Gadsby eases into a conversation about art history. She then employs a looping pattern, iteratively revisiting both subjects (humor and art) to color their meanings. We’re asked to consider her original “joke,” a story about a man confronting her at a bar. It had two components: a synthetic tension handed to the audience, and a moment of subversion which released it. The moment we accept this formulation, though, Gadsby circles back to undermine it, providing broader social context (of her own upbringing in Tasmania and the homophobia that surrounded it) that dampens the instance’s specific release—a small chuckle might temper anecdotal bigotry, but it has no firepower against society at large. Moments later she contradicts the story entirely, replacing the original ending with a horrific tale of violence and abuse—not only muting our laughter, but effectively damning it. Even that condemnation, though, is yet again re-examined and critiqued, as Gadsby confesses that her anger, while ostensibly more honest, is no more constructive than the original joke; that by denying us a punchline, she has only replaced one misleading force with another:

But this is why I must quit comedy, because the only way I can tell my truth and put tension in the room is with anger. And I am angry, and I believe I’ve got every right to be angry, but what I don’t have a right to do is to spread anger. I don’t. Because anger, just like laughter, can connect a room of strangers like nothing else. But anger, even if it’s connected to laughter, will not relieve tension because anger is a tension. It is a toxic, infectious tension. And it knows no other purpose than to spread blind hatred, and I want no part of it, because I take my freedom of speech as a responsibility, and just because I can position myself as a victim does not make my anger constructive. It never is constructive.

Her discussion of art history traces a similarly loopy arc. The traditional narrative of Van Gogh’s genius—a “tortured artist” whose creativity stemmed from mental illness—is immediately undercut by competing factors. We’re told to imagine that his medication, not his illness, was the real genesis of his creation. But no sooner have we granted this premise than she’s flipped it on its head: perhaps his story is about neither symptom nor cure, but about human connection at large. So with Picasso: a joking take-down of his simultaneous perspective technique morphs into a searing indictment of his sexual abuses, only to loop back again to the notion that he was right, metaphorically speaking, about broadening our scope.

Gadsby’s vulnerability is what lends Nanette its resonance. But what gives it longevity is her masterful construction. While her story only raises questions—does not, in her parlance, release any tension—her manner of telling hints at its own solution. The viewer may note that there is no clean thesis at the end of her monologue, or at least none that holds up in the context of repeat performance. Because the truth is that Gadsby did not, in fact, quit comedy at all. She continues, night after night, to both make people laugh and lament the failure of laughter; to give voice to outrage then denounce the tension it brings; to spread one victim’s point of view and know that it is not toxic, that it can be immensely constructive. She presents multiple views not only of the same event, but of her own presentation—leveraging self-criticism as both inoculant and weapon. She has, quite intentionally, fulfilled Picasso’s original goal. She has painted from multiple viewpoints at once.

How can we communicate conflicting feelings? How can we tear down our idols (be they Picasso or C.K.) while both learning from their impact and reiterating their indictment? How can we authentically voice our deepest anxieties—our childlike uncertainty, our adult anguish—without putting them on a pedestal and steamrolling others in our orbit? Revel in cognitive dissonance. Present the contradiction. Give the audience the tension7.

When it comes to the subject of race in America, tension is virtually inevitable. Particularly for a person of color who wishes to speak truth to a mainstream audience. For here, the issue is not primarily past trauma but perpetual harm; a message tailored to an audience complicit in its own suppression. So it’s fitting that many who thrive in this medium do so by subverting the audience’s expectations. The summer of 2018 in particular has seen the release of multiple works by black auteurs which leverage tonal dissonance as a means of expression, presenting as upbeat on first inspection only to burst into something visceral and indicting8. Here, I’ll focus on two examples: Blindspotting and BlacKkKlansman. In one, dissonance is an explicit theme, meant to be wrestled with and unpacked on screen. In the other, it’s somehow both more and less present: an uneasy subcurrent, and a concealed weapon.

Blindspotting personalizes the concept of clashing perspectives, arguing that a black man in America might experience one situation in multiple, conflicting ways. Daveed Diggs’ Collin longs to glide through life with an easy smile, but he can’t drown out the reality of gunshots—that police threat which, at any moment, might turn an innocent night out into Channel 5 news. He likens his predicament to Rubin’s figure-ground vase illusion, in which an observer will see either a light vase or two dark silhouettes depending on their choice of focus: each interpretation can only exist when the other disappears, yet any accurate description requires acknowledgement of both. Conflicting interpretations haunt everything in Collin’s world. His ex, Val, might be the only person who truly sees his goodness, but she also can’t unsee his lone moment of rage. He prides himself in being “bigger” than his anger, but he’s haunted by that anger wherever he goes. He laments the granola gentrification of Oakland, but he also (if he’s honest) likes the overpriced juice. As we criss-cross between lighthearted figure and somber ground, we’re thrust into a similarly dissonant headspace. When Collin points a gun at a murderous police officer’s head, we feel the visceral thrill of revenge; when he chooses to walk away, we feel the catharsis of letting it go. Our leads don’t ultimately choose a side, nor do they offer any conclusive reprieve. They instead exist in a superposition of states: of calm and storm, peacefulness and riot. A late act conversation explores this tension:

Collin: What did you come up with for the double picture one, the face and the vase one?

Val: Oh I liked that one, it was “blindspotting”

Collin: Why “blindspotting?”

Val: ‘Cause it’s all about how you can look at something, and there can be another thing there that you aren’t seeing, so you’ve got a blind spot.

Collin: But, if somebody points out the other picture to you, doesn’t that make it not a blind spot anymore?

Val: No, because you can’t go against what your brain wants to see first. Unless you spend the time to retrain your brain, which is hella hard. So you’re always going to be instinctually blind to the spot you aren’t seeing…

[silence]

Val: Collin?

Collin: When you look at me now, do you always see the fight first?

Perhaps more controversial is BlacKkKlansman. For the bulk of the runtime, Spike Lee’s film—a retelling of a 1970’s infiltration of the Ku Klux Klan by a black police officer—offers only the barest hint of conflict. Ron Stallworth, the officer in charge of the sting, sees little or no contradiction between his service on the force and his self-described desire for “the liberation of black people.” And he is, quite frankly, given little reason to change that: his targets are uncomplicated, bumbling racists; his peers on the force are generally decent, even heroic, save for a single, cartoonish lone wolf. His activist girlfriend might argue that he’s living a lie, that he “can’t change a corrupt system from inside.” But all signs in this fable point to the contrary.

Until the film’s final moments, when reality rears its head. After our characters achieve their inevitable victory, Lee fast-forwards four decades to modern day America. We learn that the events of the film haven’t put a dent in the true enemy; that white supremacism has not only continued, but thrived. Former caricatures are now prominent politicians. Phrases that had seemed ludicrous in Ron’s story—tirades so vile they’d bordered on comedic—are now being chanted with palpable menace. We witness the tragic events of Charlottesville through unflinching documentary footage: tiki-torched marchers, passionate counter-protesters, screeching tires, devastation. Here there is no narrative cushion, no calming retreat back into the world of fiction. Only an upside-down flag and a jarring cut to black.

Critics have argued over Lee’s true intentions—in particular, whether he is being direct or subversive in his improbably rosy take on American policing. And for a filmmaker this didactic, that context certainly matters. But I felt he was carving a third path, neither ironic nor earnest—face or vase. Rather, that he was giving voice to the lost narratives he longs to return to: the uncomplicated rights and wrongs that 70’s television had promised and society had forcefully ripped away. Good Cop Saves The Day, Bad Cop Is Taken Down By His Noble Peers, Black And White Partner Forge A Perfect Alliance™ . Today more than ever, we recognize that these technicolored fictions can’t peacefully coexist—that change can’t come from within a broken system, that “good men” don’t willingly prop up hateful peers. But there’s a reason they’ve survived this long. It feels good to take these myths for a spin; to milk one limited perspective for every ounce of hope it’s worth. So Lee gives us both, the easy triumph we wish we could have and the crushing reality that renders it impossible. He lets that whiplash speak for itself; lets our tension be its own conclusion.

Conclusion: clear and metaphor-free

Freddie, Alton, Oscar, Walter, Eric, and Stephon

Philando, Sam, Tamir and Terence, Michael, Sandra, Sean

A story never told becomes a story dead and gone

Together we can make a space where all these names live on.

– Daveed Diggs and Rafael Casal, spoken word performance (2018)That’s where you live now

Or at least that’s where I hold you

And we’re still here without you

Sleeping and the sun’s coming up

In the ruins of our household, we wake up again

Mount Eerie, “Crow, Pt. 2” (2018)

In writing this, I’ve attempted to turn a wave of independent voices into a unified story about the culture at large: tracing a dramatic arc from artifice to simplicity to vulnerability to contradiction, and tenuously stacking it beside current events. As we’ve seen, though, the world can’t be compressed into a single perspective. The truth is that art isn’t a wave, it’s a roaring rapid, with forces pulling in every conceivable direction. Upon sober reflection, the art-about-art trend of my youth was neither groundbreaking nor temporary, and the open-wound vulnerability of the Trump years has echoed throughout history. Who can listen to Otis Redding and not hear pangs of generational grief? What defines the golden age of hip hop, if not its insistence on brazen emotional truths? Direct, searing art has always existed, and the pain it mirrors is often political—be it Civil Rights anguish, Tough On Crime oppression, existential terror in times of war, or existential dread in times of peace.

Everything is cyclical: for every bleeding poet who trades melancholy for lightness, ten blistering tragi-heroes will take her place. Even the presentation of contradictions in place of a cohesive narrative, the thing that felt so present, so 2018, has been handed down through generations. Call it Vonnegut’s postmodernism or Wallace’s New Sincerity, we are always seeking some self-referential authenticity—some means of forwarding conflict directly to the audience. Toni Morrison wasn’t mourning the rise of the alt-right when she wrote her cacophonic masterpiece; neither was Zadie Smith imagining Daveed Diggs’ Oakland when she penned her own paradoxical debut9. And we don’t even need to venture beyond Spike’s own oeuvre to find the same devastating formula he employed with BlacKkKlansman—an upbeat tone unmoored by its explosive denouement. If anything, that tension is what launched his career.

Maybe it’s fairer to say, then, that the story has never really been about artistic progress, but rather about cultural receptiveness. My own receptiveness, to be more specific. My tolerance for hipness weakening with each passing political reality, my knee-jerk love of the “sincere” and “vulnerable” giving way to martyr worship and toppled altars, only to land exactly where Dawson began: the realization that our ultimate goal should be empathy, advocacy, community. “Should be to figure out our role within the context of the whole.” Artists have been shouting this in every medium, through countless “modern” trends. But it’s only now, after years of self-imposed distortion, that I’m able to hear them clearly.

Now that I do hear them, what is there to learn? When all roads lead to artifice but realism only undermines the truth, how do we honestly participate in that communion? Phil Elverum offers a glimpse of a third path. In his latest EP, Now Only, he continues to meditate on the passing of Geneviève with the same intense clarity. But absent is the paralysis of grief that haunted his previous work; that honesty so potent it threatened to blot out the sun. Instead, he intentionally muddies the waters. He considers how his life has persisted nonetheless; how those songs were not the end of anything, despite their air of logical finality. He wonders at the irony of going to a music festival, “to play these death songs to a bunch of young people on drugs” while acknowledging the limits of his sorrow, as “these waves hit less frequently” and grief “becomes calcified, frozen in stories.” And he recognizes that while life is “absurd” in the wake of this loss, it is no less vital for that absurdity. Camus would surely agree: what matters isn’t the goal but the fact of a goal, the “now only” of our irrational striving. A substance that is neither meaning nor its cynical absence. In his 10-minute epic “Distortion,” Phil paints a picture of the universe that’s eerily reminiscent to Oldham’s vision in A Ghost Story. But this time, his narrative retains its emotional tether. We may well crumble and vanish in some vast future bleakness, but the present is vibrant and gleaming:

I keep you breathing through my lungs

In a constant uncomfortable stream of memories trailing out

Until I am dead too

And then eventually the people who remember me will also die

Containing what it was like to stand in the same air with me

And breathe and wonder why

And then distortion

And then the silence of space

The Night Palace

The ocean blurring

But in my tears right now

Light gleams

In last year’s “songs about the echo,” Elverum had insisted that there was “nothing to learn”; that “conceptual emptiness” was powerless in the face of actual death. Yet far from ringing hollow, his earlier concepts strike me, today, as prophetic. This one in particular: “Lost wisdom is a quiet echo on loud wind10.” Despite the muffling gusts of heartache, he continues to tease out hidden meanings; to make more expansive art, to impart some shapeless wisdom on his listeners. Even to embrace that Sisyphean paradox, of opening himself back up to love. This summer, headlines revealed that a secret wedding had taken place among close friends and family: Phil had gotten remarried. His new bride? Michelle Williams.

Hackneyed narratives abound, here, and yet I can’t help but proffer my own—that honest despair might deepen, rather than subsume, the hope that belies it. That inbound trains are for building as well as discarding, and even disproved mountains can be gorgeous on second ascent.

So, for lack of conclusions, I’ll end where I began. In those gap years, when I was so infatuated with conscious artistry I’d lost sight of meaning, Kimya Dawson was busy speaking truths that mattered. Even—especially—when those truths seemed contradictory. To close out her Chapel set, she played one final song that lodged in my skull: an understated anthem, in my memory, of self-love and acceptance. But what I’d heard, it turns out, was only half the story. In The Uncluded’s “Teleprompters,” Dawson and Aesop Rock trade alternating fears about modern day living—and alternating mechanisms for coping nonetheless. To Dawson, the fear is in the noise: external stimuli which would shame or confuse. Her peace comes, instead, from a childhood coping mechanism; a curated inner monologue that would feel right at home alongside Rogers’ Senate recitation. To Aesop, the monologue is the sickness rather than the cure, fraught with anxiety and unsolvable social concerns. Far from silencing competing external factors, he finds solace in amplifying them, in letting communal uncertainties drown out the dread:

Kimya:

I preach self-love, I know it’s true

It’s easier to say than do

I sing these messages to you

But now I need to hear them too

I am beautiful

I am powerful

I am strong

And I am lovableAesop:

Big dummy dig a hole in the dirt

He put his head in the hole; he is alone in this world

And dying slowly from the comfort of his home full of worms

Until you hear a little voice say “Let’s go get dessert”

Wait, what?

“You need to get out more”

And clocking in some 10,000 words, I think that’s one conclusion I can safely draw: I do need to get out more. Out of this piece, these grief-tinted glasses and the seemingly blinding political glare that forced them on, my swirling cauldron of half-connected concepts that I know can’t distill with one tenth the clarity of a strummed ukulele and mention of giants—lived-in wisdom echoed through chapel roof and disco ball for an ad hoc congregation of cross-legged strangers, exiled from the past, uncertain of the future, betrayed by sincerity and sickened by cynicism, rapt, unmoored, indivisibly plural, knowing nothing sturdy or resolvable or total but a gleamingly cacophonous Now.

Acknowledgements

This essay has been gnawing at me for longer than I’d care to admit; morphing from a 2am iMessage rant to a string of beer-soaked conversations to a handful of drafts written in manic flight-and-hotel-room bursts for an audience I still haven’t quite defined. I doubt I ever would have hit the “post” button if not for some wonderfully patient people.

Chris, Jamie, Dylan, and Foh; for talking through my early post-concert ramblings and helping them start to take shape. Those (almost certainly annoying) conversations are the reason this exists. Randy, Julius, and Jake; for reading early drafts and giving valuable feedback about what was working, what wasn’t. Niels, for powering through a version of this that was somehow 50% longer (and 200% more reference-heavy) than the present monster, and helping to steer it towards something with a fighting chance of legibility. Whether I’ve succeeded on that last point is highly debatable, but know that I am personally far happier with the finished work as a result of your generosity. Daniel, for criticizing just about everything while encouraging me to post it anyway. Fuck the reviews, love the reviewers. And finally, Joanna, for continually encouraging me to write, even when it didn’t make a lick of sense. I love you, and I’m sorry in advance for the next one of these you’ll have to indulge in three, two, one…

-

I’ll also be using footnotes for some asides that, while still written to make sense with no source material familiarity, are mostly for the benefit of the film junkie (or, let’s face it, the indulgent author). If you plan on reading these, please be emotionally prepared to have The Big Sick, Swiss Army Man, Madeline’s Madeline, and All About Nina spoiled as well!↩

-

Consider the pivotal standup scene late in The Big Sick. Here, Kumail uses the stage as a vehicle for airing existential angsts: the tug-of-war between identity as anchor and identity as weight, the contradictions of familial ties, the terror of losing someone deeply loved. It recalls, to me, a particularly moving moment in Won’t You Be My Neighbor: a conversation between a child and Daniel the Tiger on the subject of death. Such simple expressions of sorrow and fear land with a thud; they defy melodrama. ↩

-

It’s hard not to be reminded of Kaufman’s orchids, here—of complex, delicate truths which the act of “making into art” might truncate rather than illuminate. ↩

-

See also: Personal Shopper.↩

-

The Big Sick, for instance, doesn’t end with Kumail’s tearful monologue: it ends with Emily (Zoe Kazan) waking up and reasserting herself. We realize that we have watched an entire romantic arc unfold while one half was literally unconscious—we’re reminded of Emily’s autonomy; that Kumail’s desire for love in no way necessitates an equal and opposite reaction. Swiss Army Man mines a similar reversal for darker purposes. Having played our heartstrings for the bulk of its runtime, we are finally introduced to the object of Hank (Paul Dano)’s high-flung affection—a terrified Mary Elizabeth Winstead. Far from an underdog, shy-guy-gets-the-girl romance, his “love” is in fact a toxic obsession—the leering of a stranger on a public bus. The engineer in me likes to think of these endings as a sort of coordinate transform, revealing a narrative shape that always existed but might have been obscured by our typical “hero-at-the-origin” framing device. And the critic in me finds it interesting, if not particularly surprising, that Kazan and Dano would soon team up to make their own film about unorthodox perspectives.↩

-

Louis C.K. and Junot Diaz, to name just two recent examples. This doesn’t appear to be an unfortunate aspect of putting “sincerity” on a pedestal; it may well be its necessary dual. By praising the bleeding artist—he who plumbs the depths of a tortured ego to eek out truth about the human condition—and mythologizing, rather than condemning, his darker dendencies, we are knowingly encouraging abusive behavior. This year’s Madeline’s Madeline goes a step further, arguing that our demand for “authentic” demons may be in itself a form of abuse. These strike me as consumer-conscious inversions of the art-as-obsession narratives given by Kaufman (Synecdoche New York) and Aronofsky (Black Swan, Mother!). Rather than imagine the artistic process as an addiction unto itself, we are now asked to consider our own satisfaction as the prime mover. If art is an attempt to transmute suffering into beauty, doesn’t our thirst for that beauty render us complicit? ↩

-

In All About Nina we see a fictional realization of the same technique. Mary Elizabeth Winstead plays the titular Nina Geld: an acerbic comedian who moves from New York to Los Angeles to try and reach a bigger audience. No longer the distant object of Paul Dano’s obsession, she now symbolizes that obsession’s righteous response: a witty anger, calloused over trauma, that guards against her male peers’ unwanted advances. For much of its runtime, the film plays as a typical rom-com—silly, sweet, and inevitably uplifting. But a sudden late-act monologue brings that mood to a halt, as Nina utterly breaks down in front of a comedy club audience. She reveals the harrowing past behind her comic persona, a story of devastating sexual violence. Here there is neither discernible build-up nor anything resembling resolution: her tension is sudden and suddenly bare, a jarring companion to the buzzy romance that preceded it. It’s breathtaking. It’s odd. It is, as director Eva Vives later revealed, largely autobiographical; a complicated tension which only whiplash could express. To cushion or resolve it would be a disservice to the truth.↩

-

Childish Gambino’s “This Is America” may be the most concise example of this technique, and the earliest to hit a wider audience this year. The comedian-turned-rapper’s music video is a dizzying protest piece grounded in dissonance: a smiling dance through gun violence and societal upheaval, set to a catchy, upbeat rhythm. Much has been written (by far wiser critics) about the themes Donald Glover is wrestling with. What strikes me most is how little wrestling he must portray to get his point across. The feeling is the story: to recap it on substance alone is to profoundly miss the point. One may well miss the resonance of a particular gospel choir, but none could escape that underlying tension—an uneasy alliance of horror and joy that feels unmistakably political. It isn’t nihilism; it’s a weaponized contradiction. Sorry To Bother You features a similar tension between lighthearted tone and devastating content, but the targets of its satire are far more concrete—hinting at proactive solutions which, while crucial, fall outside the scope of this piece.↩

-

This excerpt from White Teeth, in particular, would feel right at home in Blindspotting. “But multiplicity is no illusion. Nor is the speed with which those-in-the-simmering-melting-pot are dashing toward it. Paradoxes aside, they are running, just as Achilles was running. And they will lap those who are in denial just as surely as Achilles would have made that tortoise eat his dust. Yeah, Zeno had an angle. He wanted the One, but the world is Many. And yet still that paradox is alluring. The harder Achilles tries to catch the tortoise, the more eloquently the tortoise expresses its advantage. Likewise, the brothers will race toward the future only to find they more and more eloquently express their past, that place where they have just been. Because this is the other thing about immigrants (’fugees, émigrés, travelers): they cannot escape their history any more than you yourself can lose your shadow.”↩

-

As if to demonstrate just how infused this concept is in Phil’s art, it wasn’t until after I’d written this final draft (title and all) that I caught Elverum’s own explicit tie-in between these works. Namely, in the closing track of Now Only, “Crow, Pt. 2”: “You’re a quiet echo on loud wind.”↩