If there’s one thread that runs through the “Modern Indie,” it’s a refusal to compartmentalize the human experience. Everything and nothing are sacred, profound. And in a world full of Melodrama and Very Special Episodes™ , that usually means subversion. Banal experiences get elevated to universal truths; lofty ideals and characters come crashing down to earth. It’s a contortion act that tends to call attention to itself.

Room is subverting something, but you never feel that strain. Conceptually it reads like a terrifying Very Special Episode : a girl is abducted by “Old Nick” and locked in his shed. Two years in, she gives birth to a son. Seven years in, she devises a plan to free him. Yes, it is harrowing. No, it’s nothing like The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. If ever a subject matter earned its melodrama — long tearful monologues, slow-motion embraces — this would be it. Far be it for me, or the movie, to sneer.

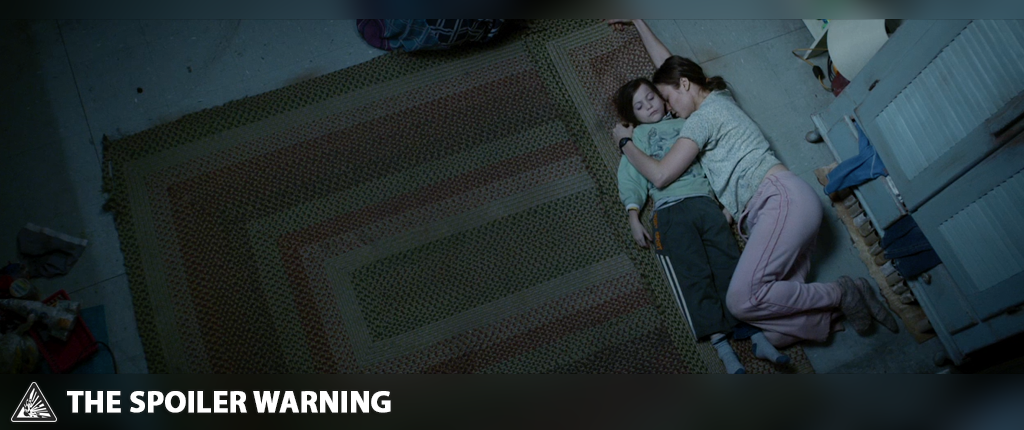

And it doesn’t sneer. Nor does it avoid those long tearful monologues or slow-motion embraces, when appropriate. But its terrifying concept isn’t heightened to melodrama or irreverently flipped: it’s just context. A terrible thing happened, and rather than dwell on how sad life would be, the bulk of the movie simply asks “what would life be?”, playing more like a documentary than a drama. When we meet Joy (“Ma”), she’s settled into her sad routine. Jack, now five, has only seen the world through a television set. Like Life Is Beautiful’s Joshua, he navigates his circumstance through a universe of Joy’s invention, full of mechanisms and constraints that we only glimpse in passing. Things in Room are real. Things in TV are fake. Bed is real and Bowl is real, but Dog and Tree and TV things. Sometimes Old Nick brings TV things into Room, but it comes at a high cost.

Brie Larson is getting awards buzz over her turn as Joy, and for good reason. It’s one of those half-invisible performances that’s so believable you forget to notice it. The whole movie felt a bit like that to me: for such heart-wrenching material, it stays remarkably down to earth. Joy is a wonderful parent, but she’s also bitter and less mature than she’s forced to pretend. Jack has his adorable moments, but also abrasive, petty, and downright annoying ones. And just like the first half argues that tragedy can’t overwhelm life, the second half shows that joyful circumstances can’t monopolize it. To someone looking for a feel-good movie, that might be a bitter pill to swallow. I loved it, because I believed it.

Avoid trailers at all costs, and seek this one out.