I love standup comedy. I also love media that is at least peripherally about the world of comedy, as told by those who live in it. Don’t Think Twice. Crashing. WTF with Marc Maron. The Big Sick. If there’s a common thread here, beyond the occupation of its subjects (and creators), it’s that each treat humor as a thinly-veiled coping mechanism, a public exorcism of personal demons. Heartbreaking monologues that seem to arise fully formed; the stage as device for uttering the unutterable; all the insight of an omniscient narrator with none of the cheeseball.

That list also summarizes what I love about Mary Elizabeth Winstead’s acting: her ability to unravel tangled emotions in long, unbroken takes. With a camera trained on her for nearly its entire runtime, 10 Cloverfield Lane may be the most obvious showcase, but my personal favorite is Smashed. Having hit rock bottom (as the title implies), Winstead’s Kate is asked to tell her story at an AA meeting. Over the course of one extended monologue, she flows from reluctance to skepticism to denial to detachment to caution to fearful, full-throated vulnerability. It might just be the best performance of 2012, and it singlehandedly makes the film.

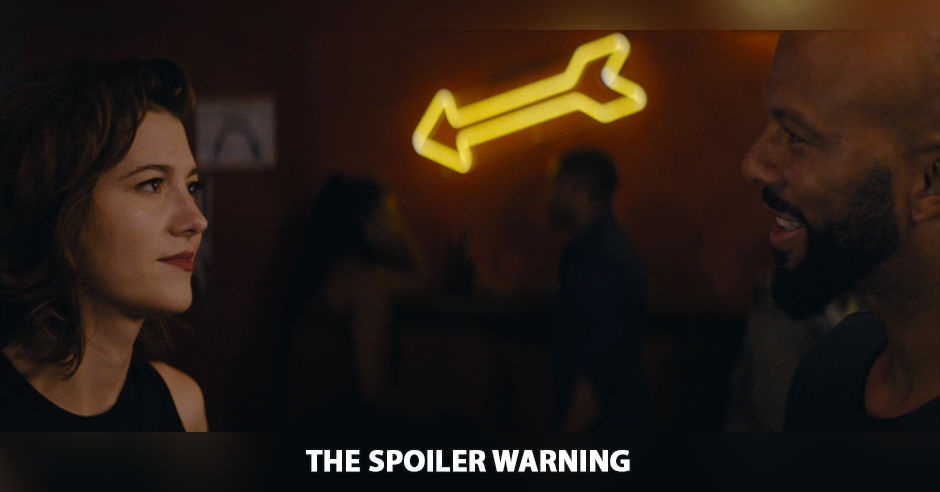

All About Nina (3.5/5) features a similarly stunning, film-making monologue. Winstead’s titular Nina is now an acerbic standup comedian rather than an alcoholic teacher, but she’s exorcising demons just the same; peeling back guarded layer upon guarded layer to get to something true. Something that stings, that I wouldn’t dare spoil for you. It’s a beautiful moment in a performance packed with them, and it’s likely my single favorite scene of the festival. It’s also a culmination of so many things I care about in art: confessional storytelling, raw emotion, the antihero-rich world of standup comedy. So why am I not more bullish on this?

Part of the problem, I think, is tone. Eva Vives has constructed a film that absolutely sidelines you. This is by design. All About Nina is a heavy-hitting drama in hindsight, but for much of its runtime it plays as a lighthearted rom-com. See, having cut her teeth in the New York comedy scene, Nina now finds herself friendless in Los Angeles. She’s there to fulfill her dream of landing a gig at Comedy Prime, the weekly sketch show produced by mysterious kingmaker “Larry Michaels” (GET IT EVERYBODY?! GET IT?!). “Sketch” is the operative word here — after moving to the best coast, Nina meets a host of barely-drawn secondary characters: a pop spirituality author who introduces her pronoun preferences before saying hello, a drum-circling support group raising money for a “cat sanctuary”, a brash-talking agent who’s liable to stay in the office till her water breaks, and an alt comic who literally shits her pants on stage. It’s all perfectly funny, if a bit West-Coast-as-seen-by-a-New-Yorker hack. But orbiting the incredibly believable (as a standup and a person) Nina, it throws the narrative into the uncanny valley. If this world is a satire, why do I feel so invested? If the world is real, why does so much of it feel corny?

Speaking of corny, let’s talk about the common problem shared between this one and Blue Night; or, rather, the Common problem. As in Lonnie Lynn. Don’t get me wrong, I love the guy, and I don’t think his acting chops are the problem. He oozes nothing but peace, love, and authenticity, both on and off the stage. But maybe that’s the problem: his charisma is so unique and self-insisting, he’s physically incapable of hiding behind a character who isn’t also secretly Common. Or, at least, I’m incapable of sharing the delusion. Here he plays Rafe, the Nice Guy antidote to Nina’s Bad Boy relationship streak. Whether wooing her at a bar, sharing a starlit heart-to-heart, or engaging in an implausible third act shouting match, he possesses an almost otherworldly charm. As a love interest in a spoof of the LA comedy scene, that might be perfect; as a catalyst for change in a film meant to be taken seriously, I found it unbelievably distracting. After Nina riffs on stage about the gap between her sensibilities and Nicholas Sparks’, I couldn’t help but think that the script would benefit from the same separation — for all the talent elevating the material, the romance itself is cookie-cutter Sparks. And it suffers for it. Still, quite a few others have praised Common’s work here (Chris in particular), so take my criticism with a grain of salt. And water, and chocolate.

Ultimately, this is a very good movie that carries a handful of pretty mediocre movies on its back. The core is wonderful, and thankfully the narrative thrust — Winstead’s turn alone is well worth the price of admission. It’s my favorite performance of hers to date. I just wish the film would have cut the dead weight, and realized that it’s possible for a movie to be disarmingly funny while still taking itself (and the audience) seriously. Chris and I argue about standup, the relative virtues of Common, and my massive hypocrisy in another Tribeca episode: