Things I wanted to see but hadn’t yet: Okja, BPM, Your Name, Faces Places, Loving Vincent, Foxtrot, Wonderstruck

More ramblings: if one novel isn’t enough for you, you can also find my 2016, 2015, and 2014 lists.

Podcast: you can listen to a similar (but not identical) list I gave with my friends over at The Spoiler Warning.

Introduction

Every year, when it comes time to make one of these Top 10 lists, I’m reminded of how arbitrary the ranking process is. After all, if a stranger asked you to recommend an album, you’d never just rattle off your five personal favorites and call it a day. You’d first try to hone in on a more tractable question: “well, what kind of music do you like?” Because music, like all art — like all things — can’t be judged by some objective metric. It’s only good insofar as it made you feel something; and whether that thing you felt is the particular sort you came in looking for.

And yet, maybe because film is a smaller medium (i.e. critics really can see everything), I always forget that impossibility come January. I find myself agonizing over orderings, or the relative merits of various performances — comparing comedy to biopic to coming-of-age to romance as if any could be meaningfully “less” than the other. The truth is that, despite critical consensus, Lady Bird is not the best film of the year. Neither is Dunkirk, or Get Out, or Call Me By Your Name, or The Post. (Especially not The Post…) There is no Best Film, because there’s no Best Statement; no end goal or message which every filmmaker aspires to. It’d be a terribly boring world if there were.

So, while I always violate the terms of a Top 10 to some degree, this year I’m really opening the floodgates. To answer what, I hope, is a more meaningful question: what were the various statements of 2017, and how did they move me? To assist that (and to squeeze in double what the limit allows), I’m counting down pairs of films which orbit similar themes or pose similar questions. There’s a rough ordering here somewhere (the films in my #1 spot are probably more dear to me than those in my #10 spot), but it’s intentionally muddied by the grouping. In general, my favorite member of the pair determined its location on the list — so while flattening this into a Top 20 would be wrong, it’d be no more than 50% wrong (and quite a bit less, as luck would have it!) Feel free to check the podcast for a more cutthroat ranking. Or, better, ignore ranking entirely and just enjoy the good stuff.

10. Coming Of Age In Uncertainty: Lady Bird and Landline

Coming-of-age flicks are particularly revealing, because they act as a sort of barometer for the culture at large. What do we wish we could impart to our younger selves? What is the essential truth we’d distill? Maybe it’s a reaction to the politics of 2016, but this year the answer seems to be a nonanswer: no one has a goddamn clue.

Greta Gerwig has always been the best part of whatever she’s in, to the point where she arguably transforms the filmmakers who work with her. You can draw a straight line from the frank sex of Nights and Weekends to Swanberg’s love-in-the-technology-era Easy; can feel her practically dragging Noah Baumbach up from the subdued charms of Greenberg to the rapture of Frances Ha to the unrestrained slapstick of Mistress America (full review). She’s a light in bitter places, an advocate for full-throated pathos in all things, and she leaves people better than she found them. I love her artistic voice. And yet, I never predicted the impact Lady Bird would have.

Greta Gerwig has always been the best part of whatever she’s in, to the point where she arguably transforms the filmmakers who work with her. You can draw a straight line from the frank sex of Nights and Weekends to Swanberg’s love-in-the-technology-era Easy; can feel her practically dragging Noah Baumbach up from the subdued charms of Greenberg to the rapture of Frances Ha to the unrestrained slapstick of Mistress America (full review). She’s a light in bitter places, an advocate for full-throated pathos in all things, and she leaves people better than she found them. I love her artistic voice. And yet, I never predicted the impact Lady Bird would have.

My gut response to the overwhelming acclaim of Lady Bird was skepticism — navigating-senior-year-of-highschool indie flicks are a dime a dozen, so why did this one hit critics so hard? And, honestly, I still don’t have a satisfying answer. But I think the secret lies in her use of lightness to disarm us. Saoirse Ronan’s titular protagonist checks off plenty of boxes (first heartbreak, first sexual encounter, first major act of rebellion), and they’re sketched with all the specificity of lived-in experience. But there’s never a tidy lesson to learn from them: no one to blame, no one to hate, no third act redemptive do-over. Her parents (Laurie Metcalf and Tracey Letts, both wonderful) are flawed and conflicted in their attempts to control and befriend her, but those conflicts never even hint at a resolution. The film, instead, functions as a bright, vulnerable shrug emoji: when we leave we have no idea what the “right” path is, or how any of this will work out. The only certainty, is that none of this gets easier.

***

Gillian Robespierre is no stranger to gray areas herself: her 2014 comedy Obvious Child may have drawn headlines for its subject matter (abortion), but what made it truly bold was its refusal to moralize on the subject. It certainly wasn’t a tacitly pro-life statement (as Juno or Knocked Up might be misconstrued); but neither was it a pointedly pro-choice rallying cry. It was a human film, concerned solely with the woman at the center: Jenny Slate’s Donna, for whom the same act could be a source of pain, relief, and a very funny standup routine to boot.

Gillian Robespierre is no stranger to gray areas herself: her 2014 comedy Obvious Child may have drawn headlines for its subject matter (abortion), but what made it truly bold was its refusal to moralize on the subject. It certainly wasn’t a tacitly pro-life statement (as Juno or Knocked Up might be misconstrued); but neither was it a pointedly pro-choice rallying cry. It was a human film, concerned solely with the woman at the center: Jenny Slate’s Donna, for whom the same act could be a source of pain, relief, and a very funny standup routine to boot.

Landline continues Robespierre’s humanistic streak, this time tackling infidelity. Edie Falco and John Turturro are parents struggling to keep a stagnant marriage alive. Their oldest daughter Dana (Slate) may have changed a vowel since her previous film, but her station in life is otherwise unmoved: standing at the threshold of a new phase of adulthood (marriage), and terrified. So terrified, she blows it up. Watching both relationships strain is Ali, the youngest of the family, a high school senior who can’t seem to muster up the energy to care about the future. After all, why care when this is how it ends up? When your dad is a scumbag and your mother is trapped and your sister’s visibly self-imploding; when everything is as black-and-white and personal as it seems to a teenager, who wants to write an essay about Michigan State? Like Lady Bird, there are no tidy resolutions here; but unlike Lady Bird, the audience has seen enough “wrongs” to truly feel owed a few. Ali doesn’t exact some cosmic justice on behalf of her mother; Dana doesn’t trace any grand prodigal arc. People will fail. People are complicated. You will fail. Keep trying.

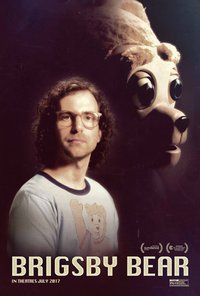

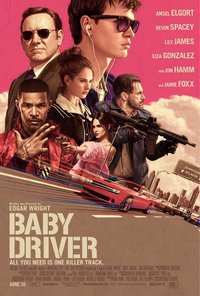

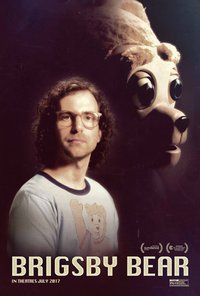

9. Entertainment As Escape: Brigsby Bear and Baby Driver

So what solace do we take in a world that lacks easy answers? Two films this year reminded me that, for all the quote grand messages endquote of cinema, sometimes it functions best as a grand distraction: a relief from, rather than reminder of, the complicated world around us.

Brigsby Bear is nearly impossible to explain without giving away its central premise, and that premise may be its most delightful aspect. Part Room and part The Disaster Artist, it’s the story of a man (Kyle Mooney) who has only seen a single television show: a cheesy, dated, Barney-esque educational series named “Brigsby Bear.” Stranger still, he’s the only one who’s seen it. So when circumstances arise which permanently take the show off the air, he feels an odd sort of weight — this thing was his, and now it’s gone, and no else is even aware of its absence. He copes with this loss the only way he knows how: by making more episodes. Donning an enormous bear mask and a Public Access-worthy collection of props, James and his friends recreate the bewildering universe of Brigsby. It’s a movie about how entertainment gives color and texture to our world; how consuming it lets us escape from life’s difficulties, and how creating it lets us transform them into joy. The cast is uniformly great, but the true standout is Mark Hamill, giving his best turn as a knowledge-bestowing hermit this year — The Last what, now? One the pleasant surprises of 2017.

Brigsby Bear is nearly impossible to explain without giving away its central premise, and that premise may be its most delightful aspect. Part Room and part The Disaster Artist, it’s the story of a man (Kyle Mooney) who has only seen a single television show: a cheesy, dated, Barney-esque educational series named “Brigsby Bear.” Stranger still, he’s the only one who’s seen it. So when circumstances arise which permanently take the show off the air, he feels an odd sort of weight — this thing was his, and now it’s gone, and no else is even aware of its absence. He copes with this loss the only way he knows how: by making more episodes. Donning an enormous bear mask and a Public Access-worthy collection of props, James and his friends recreate the bewildering universe of Brigsby. It’s a movie about how entertainment gives color and texture to our world; how consuming it lets us escape from life’s difficulties, and how creating it lets us transform them into joy. The cast is uniformly great, but the true standout is Mark Hamill, giving his best turn as a knowledge-bestowing hermit this year — The Last what, now? One the pleasant surprises of 2017.

***

Is there a more consistent filmmaker in Hollywood than Edgar Wright? Love him or leave him, his movies always deliver on precisely what their trailers promise. Hell, they’re effectively feature-length trailers: razor-sharp edits, rip-roaring soundtracks, and quotable quips delivered by genre-fied characters who (impossibly) earn them. If Scott Pilgrim proved the formula, Baby Driver might prove its hypothetical limit: it’s a deliriously fun joyride through style over substance, with style approaching infinity and substance zero. Ansel Elgort’s Baby acts as an audience surrogate, driving his getaway car to the rhythm of a non-stop classic rock playlist. Inseparable from his headphones, Baby is most at peace when he’s drowning in stimulation. Cars skid, cameras veer, and a star-studded cast chews diesel-drenched set dressing while Queen and Blur blare triumphant. If Brigsby Bear was the best film about escape, Baby Driver might be the best example of it: pure, cinematic joy.

Is there a more consistent filmmaker in Hollywood than Edgar Wright? Love him or leave him, his movies always deliver on precisely what their trailers promise. Hell, they’re effectively feature-length trailers: razor-sharp edits, rip-roaring soundtracks, and quotable quips delivered by genre-fied characters who (impossibly) earn them. If Scott Pilgrim proved the formula, Baby Driver might prove its hypothetical limit: it’s a deliriously fun joyride through style over substance, with style approaching infinity and substance zero. Ansel Elgort’s Baby acts as an audience surrogate, driving his getaway car to the rhythm of a non-stop classic rock playlist. Inseparable from his headphones, Baby is most at peace when he’s drowning in stimulation. Cars skid, cameras veer, and a star-studded cast chews diesel-drenched set dressing while Queen and Blur blare triumphant. If Brigsby Bear was the best film about escape, Baby Driver might be the best example of it: pure, cinematic joy.

8. Love As Agent Of Change: The Big Sick and Phantom Thread

Oscar Wilde said that “Everything in the world is about sex, except sex,” and there might be a similar rule for love stories. Everything is obliquely a romance, but those films which tackle love head-on are rarely about the feeling itself. Instead, they’re about what love does; what it signifies to one or both characters, and what it changes or demands.

On its surface, The Big Sick is just about about as heartfelt a love story as you can get. And as a lover of standup, and a particular fan of Kumail and Emily’s, I fully expected it to move me. I just hadn’t anticipated why it’d move me. In heavier hands, the story might have written itself: love beset by tragedy, humor as a bulwark against hopelessness, light at the end of the blah blah blah credits. It would have tugged heartstrings, and it would have been earned. But The Big Sick foregoes tugging for a more precise operation, revealing tiny layers of truth behind the bleeding-heart drama. Truths about growing up and finding your voice; about the burden of family and religion and culture, and the delicate maneuver of “breaking free” without severing or diminishing their weight. It’s about the changes Emily demands of Kumail by virtue of her existence: her refusal to be sidelined, to be swept under the rug of “private life” to an overbearing family; the way she forces him to reckon with his own identity and worth. It’s about how guarded passivity strains our relationships, and uncompromising honesty becomes its own higher brand of love — messy, hurtful, and wholly undivided. Avoid spoilers if you want; this isn’t, ultimately, about a meet-cute or coma. Those are handled beautifully, but there’s a deeper healing (and awakening) at play.

On its surface, The Big Sick is just about about as heartfelt a love story as you can get. And as a lover of standup, and a particular fan of Kumail and Emily’s, I fully expected it to move me. I just hadn’t anticipated why it’d move me. In heavier hands, the story might have written itself: love beset by tragedy, humor as a bulwark against hopelessness, light at the end of the blah blah blah credits. It would have tugged heartstrings, and it would have been earned. But The Big Sick foregoes tugging for a more precise operation, revealing tiny layers of truth behind the bleeding-heart drama. Truths about growing up and finding your voice; about the burden of family and religion and culture, and the delicate maneuver of “breaking free” without severing or diminishing their weight. It’s about the changes Emily demands of Kumail by virtue of her existence: her refusal to be sidelined, to be swept under the rug of “private life” to an overbearing family; the way she forces him to reckon with his own identity and worth. It’s about how guarded passivity strains our relationships, and uncompromising honesty becomes its own higher brand of love — messy, hurtful, and wholly undivided. Avoid spoilers if you want; this isn’t, ultimately, about a meet-cute or coma. Those are handled beautifully, but there’s a deeper healing (and awakening) at play.

***

You’d be hard-pressed to find a less traditional love story than Phantom Thread. And yet, in Paul Thomas Anderson’s delightfully twisted way, love is exactly what it deconstructs. A worthy companion piece to Aronofsky’s (insufferable) mother!, Phantom Thread is interested in the egomania that drives creative expression, and the near-impossibility of finding love within that framework. Daniel Day Lewis’ Woodcock, like Bardem’s nameless Artist, stalks his household with a cruel singularity of focus. He shouts at everyone who tries to help him. He torments the one woman, Alma (a wonderful Vicky Krieps), who truly loves him. His withering silence is more abusive than any torrent of expletives, and he wields it like a dagger. Set in the high fashion culture of 1950’s London, the film is brimming with visual charm even as its lead grows monstrous and terrifying. But what truly sets it a part, and earns it a place on this list, is its third act coup — a twist which casts Woodcock and Alma’s relationship in a light I still haven’t really unpacked. It suggests a violent sort of love which is, like Wilde’s sex, indeed about power — but less about asserting it than properly regulating it. Love might be at its most powerful when it brings us to our lowest, dampening selfish instinct before it tips from “agent of creativity” to “agent of chaos.” This chilly, check-and-balance, mutually-assured-destruction view of love may not be the most heartwarming of the year. But I’m finding it hard to shake.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a less traditional love story than Phantom Thread. And yet, in Paul Thomas Anderson’s delightfully twisted way, love is exactly what it deconstructs. A worthy companion piece to Aronofsky’s (insufferable) mother!, Phantom Thread is interested in the egomania that drives creative expression, and the near-impossibility of finding love within that framework. Daniel Day Lewis’ Woodcock, like Bardem’s nameless Artist, stalks his household with a cruel singularity of focus. He shouts at everyone who tries to help him. He torments the one woman, Alma (a wonderful Vicky Krieps), who truly loves him. His withering silence is more abusive than any torrent of expletives, and he wields it like a dagger. Set in the high fashion culture of 1950’s London, the film is brimming with visual charm even as its lead grows monstrous and terrifying. But what truly sets it a part, and earns it a place on this list, is its third act coup — a twist which casts Woodcock and Alma’s relationship in a light I still haven’t really unpacked. It suggests a violent sort of love which is, like Wilde’s sex, indeed about power — but less about asserting it than properly regulating it. Love might be at its most powerful when it brings us to our lowest, dampening selfish instinct before it tips from “agent of creativity” to “agent of chaos.” This chilly, check-and-balance, mutually-assured-destruction view of love may not be the most heartwarming of the year. But I’m finding it hard to shake.

7. Pain As Catalyst For Growth: Stronger and The Work

Sometimes growth is forced upon us by others, but sometimes it comes from within; from the deliberate, painful, day-in-day-out grind of self betterment. Two films, one biopic and one documentary, highlight the human struggle at the heart of change.

Stronger tells the true life story of Jeff Bauman (Jake Gyllenhaal), a 27-year-old Boston native who lost both his legs in the Marathon bombings. I’ll be honest: I didn’t have high hopes for this one. With an incident so fresh, and so overtly heartbreaking, the risk of deification (see: 21st century Clint Eastwood) or twisting suffering into a cheap sort of martyrdom, is high. So I was floored to see how David Gordon Green tackled this material. The inciting events, and the subsequent heroism, take up maybe the first 20 minutes of the film. The rest is devoted not to enshrining our protagonist, but to dismantling the cost of hero worship: the toll of presenting as “strong” to the outside world, while struggling with feelings of worthlessness inside. Gyllenhaal is an absolute revelation here, revealing the wounded, guarded impotence behind Bauman’s easy exterior. Never wholly good nor wholly bad, he wants to do the right thing — mostly. But he also wants the love of his on-again-off-again girlfriend Erin, and he isn’t above woe-is-me manipulation to get it. This is a film that lets no one off the hook. It says that intentions are only the first step; that true growth is a constant struggle, and some days we fail it. On the best days, though, our successes might be magnified by the humanity of past failure. Jeff Bauman is a flawed man striving to fill out the image of a hero. And that might be more inspirational than the real, impossible thing.

Stronger tells the true life story of Jeff Bauman (Jake Gyllenhaal), a 27-year-old Boston native who lost both his legs in the Marathon bombings. I’ll be honest: I didn’t have high hopes for this one. With an incident so fresh, and so overtly heartbreaking, the risk of deification (see: 21st century Clint Eastwood) or twisting suffering into a cheap sort of martyrdom, is high. So I was floored to see how David Gordon Green tackled this material. The inciting events, and the subsequent heroism, take up maybe the first 20 minutes of the film. The rest is devoted not to enshrining our protagonist, but to dismantling the cost of hero worship: the toll of presenting as “strong” to the outside world, while struggling with feelings of worthlessness inside. Gyllenhaal is an absolute revelation here, revealing the wounded, guarded impotence behind Bauman’s easy exterior. Never wholly good nor wholly bad, he wants to do the right thing — mostly. But he also wants the love of his on-again-off-again girlfriend Erin, and he isn’t above woe-is-me manipulation to get it. This is a film that lets no one off the hook. It says that intentions are only the first step; that true growth is a constant struggle, and some days we fail it. On the best days, though, our successes might be magnified by the humanity of past failure. Jeff Bauman is a flawed man striving to fill out the image of a hero. And that might be more inspirational than the real, impossible thing.

***

The Work may be the most appropriately titled film of the year. Set over a four-day intensive therapy session between inmates and visitors at Folsom Prison, it’s a documentary about the hard, hard work of emotional growth. Picture this: ten to twelve people, primarily convicts serving near-life sentences for violent crimes, stand in a circle. The instructor asks one member to share his story. Staring firmly at the floor, he opens up about the events that led to Folsom — a gang-related murder — and the years he’s spent in wait. He misses his family, but he can’t properly mourn them, because to properly feel anything would be to feel the horror of the prison system and the enormity of his loss. One by one, peers tease out details, urging him to confront things head-on, until suddenly, tears. Release. He’s on the ground, and he’s screaming in a way you’ve never heard a grown man scream. Five dogpile to restrain him while he pushes, fights, vents every ounce of aggression into this thing he’s fortified against for years. Eventually his energy runs out, and we rejoin the circle.

The Work may be the most appropriately titled film of the year. Set over a four-day intensive therapy session between inmates and visitors at Folsom Prison, it’s a documentary about the hard, hard work of emotional growth. Picture this: ten to twelve people, primarily convicts serving near-life sentences for violent crimes, stand in a circle. The instructor asks one member to share his story. Staring firmly at the floor, he opens up about the events that led to Folsom — a gang-related murder — and the years he’s spent in wait. He misses his family, but he can’t properly mourn them, because to properly feel anything would be to feel the horror of the prison system and the enormity of his loss. One by one, peers tease out details, urging him to confront things head-on, until suddenly, tears. Release. He’s on the ground, and he’s screaming in a way you’ve never heard a grown man scream. Five dogpile to restrain him while he pushes, fights, vents every ounce of aggression into this thing he’s fortified against for years. Eventually his energy runs out, and we rejoin the circle.

I’m not positive how I feel about the methods used in The Work. Like AA or a bestselling self help book, there’s a certain sheen to their dialogue — an overemphasis on mysticism, on spiritual affirmations and the value of the experience — that feels performative. The camera is always felt, an intrusive observer which modifies the result. But that’s precisely what makes this documentary so fascinating. We sense that these people truly want to bare something, be it for personal satisfaction or documentary fame or a positive mark in an upcoming parole hearing. And we watch how they grapple with that desire, how they verbalize or perform it. To a man who has known only aggression, it might be physical; wrestling with pain, shouting at it, beating it to a pulp. To a father fearing for his own child, quiet words of paternal support (“you are enough, son, you are loved”) ring truer than any profound psychic revelation: projecting on himself the love he wishes he could give his son. Maybe the things that I receive as hokey and over-sentimental — platitudes about masculinity, intrinsic worth — are overused precisely because they’re needed. Because they’re what we crave when we’ve lost everything else. Regardless of truth, watching these men at the end of their rope, grasping for any available tool to express themselves…it’s a profound, spiritual experience.

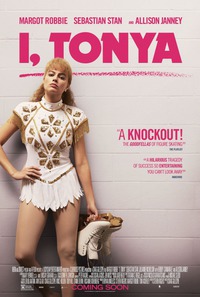

6. Grappling With History: The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) and I Tonya

Regret was a major theme of 2017, and it doesn’t take much digging to guess as to why. From Brad’s Status to Star Wars (full review), many begged the question: where did it all go wrong? Two films in particular highlighted the subjective nature of past experience. Using competing narratives and a Rashomon-like recasting of events, they’re about the way we struggle to make sense of the present in light of the past — our past, that is. The story that we, and only we, get to tell.

It might seem presumptuous to use such lofty terms for The Meyerowitz Stories, Noah Baumbach’s direct-to-Netflix comedy about three adults coping with an obnoxious father. On paper it reads like Baumbach’s take on The Royal Tenenbaums — or a spiritual sequel to The Squid And The Whale — and there are similarities to be sure: like many films this year, there’s a relentlessly self-obsessed artist (Dustin Hoffman) at its center. But I’d argue this film is less about classic familial dysfunction, and more about the way bitterness and self-questioning get passed down like family heirlooms. Hoffman’s patriarch is mired in history, constantly comparing himself to his more successful peers. Ben Stiller’s Matthew struggles to fill the role of “favorite son”, never quite able to earn or outrun it. Adam Sandler’s Danny never had any delusions of being the “favorite”; a talented childhood having given way to a less-than-dazzling adulthood, he has little but a limp, a divorce, and a college-bound daughter to his name. He loves being the sort of father his own wasn’t, but now that his daughter no longer needs him, who exactly is left in that identity? Elizabeth Marvel’s Jean is the only one who seems to have made peace with her past, despite hints of darkness beyond any Matthew and Danny experienced. There’s a real sadness at the core of this comedy, particularly in Stiller and Sandler’s world-weary portrayals of middle age. These are adults with grown children of their own, but deep down they’re still relitigating what they lost in their youth. A song at the piano early in this film, between Danny and his college-bound daughter, made me tear up despite having barely known these characters. And that pathos continues through the bitterest of scenes. It’s a lovely, wistful little flick.

It might seem presumptuous to use such lofty terms for The Meyerowitz Stories, Noah Baumbach’s direct-to-Netflix comedy about three adults coping with an obnoxious father. On paper it reads like Baumbach’s take on The Royal Tenenbaums — or a spiritual sequel to The Squid And The Whale — and there are similarities to be sure: like many films this year, there’s a relentlessly self-obsessed artist (Dustin Hoffman) at its center. But I’d argue this film is less about classic familial dysfunction, and more about the way bitterness and self-questioning get passed down like family heirlooms. Hoffman’s patriarch is mired in history, constantly comparing himself to his more successful peers. Ben Stiller’s Matthew struggles to fill the role of “favorite son”, never quite able to earn or outrun it. Adam Sandler’s Danny never had any delusions of being the “favorite”; a talented childhood having given way to a less-than-dazzling adulthood, he has little but a limp, a divorce, and a college-bound daughter to his name. He loves being the sort of father his own wasn’t, but now that his daughter no longer needs him, who exactly is left in that identity? Elizabeth Marvel’s Jean is the only one who seems to have made peace with her past, despite hints of darkness beyond any Matthew and Danny experienced. There’s a real sadness at the core of this comedy, particularly in Stiller and Sandler’s world-weary portrayals of middle age. These are adults with grown children of their own, but deep down they’re still relitigating what they lost in their youth. A song at the piano early in this film, between Danny and his college-bound daughter, made me tear up despite having barely known these characters. And that pathos continues through the bitterest of scenes. It’s a lovely, wistful little flick.

***

I, Tonya has a similar blend of acridity and wit, but the tone it strikes is less wistful than defiant. In one of the year’s absolute best performances, Margot Robbie imbues Tonya Harding with all the love-me-or-leave-me stubbornness of a punk icon. She has the unique capacity to hurt that can only come from having been hurt herself. She sees the world as deeply unfair, and, honestly, I’m inclined to agree. We don’t just watch her story; we watch every possible interpretation of her story. Like last year’s experimental documentary Tower, the script features fictionalized reenactments of real-world interviews: Tonya, her alcoholic mother (a scenery-chewing Allison Janney), her abusive ex-husband, her “bodyguard”, and the paparazzi all weigh in, interject. While that leaves room for plenty of fourth-wall-breaking playfulness, it also lends I, Tonya a bold subjectivity. Unlike most biopics, Gillespie’s explicitly acknowledges its biases and leverages them as strengths. Where other films might restrain scenes of domestic abuse in an effort to be even-handed, Gillespie frees them to be both monstrously evil and cartoonishly good, to be exactly as Tonya perceived them and as they aspirationally perceive themselves. There’s something electric, anarchic, about all that mayhem, like watching someone take a wrecking ball to their own family tree. Maybe Tonya was a tragic victim of circumstance. Maybe she was a self-serving, opportunistic brat. Maybe she knew nothing about the Kerrigan affair, maybe she orchestrated the whole thing, or maybe the truth lies somewhere in between. Only one thing stays consistent amid the heightened counter-narratives: on or off the rink, the girl was a force to be reckoned with. Now sit back and reckon with her.

I, Tonya has a similar blend of acridity and wit, but the tone it strikes is less wistful than defiant. In one of the year’s absolute best performances, Margot Robbie imbues Tonya Harding with all the love-me-or-leave-me stubbornness of a punk icon. She has the unique capacity to hurt that can only come from having been hurt herself. She sees the world as deeply unfair, and, honestly, I’m inclined to agree. We don’t just watch her story; we watch every possible interpretation of her story. Like last year’s experimental documentary Tower, the script features fictionalized reenactments of real-world interviews: Tonya, her alcoholic mother (a scenery-chewing Allison Janney), her abusive ex-husband, her “bodyguard”, and the paparazzi all weigh in, interject. While that leaves room for plenty of fourth-wall-breaking playfulness, it also lends I, Tonya a bold subjectivity. Unlike most biopics, Gillespie’s explicitly acknowledges its biases and leverages them as strengths. Where other films might restrain scenes of domestic abuse in an effort to be even-handed, Gillespie frees them to be both monstrously evil and cartoonishly good, to be exactly as Tonya perceived them and as they aspirationally perceive themselves. There’s something electric, anarchic, about all that mayhem, like watching someone take a wrecking ball to their own family tree. Maybe Tonya was a tragic victim of circumstance. Maybe she was a self-serving, opportunistic brat. Maybe she knew nothing about the Kerrigan affair, maybe she orchestrated the whole thing, or maybe the truth lies somewhere in between. Only one thing stays consistent amid the heightened counter-narratives: on or off the rink, the girl was a force to be reckoned with. Now sit back and reckon with her.

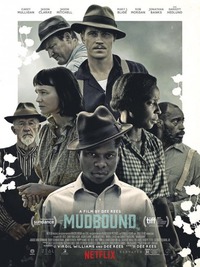

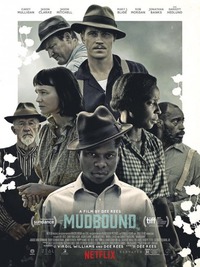

5. Forging An Identity: Mudbound and Blade Runner 2049

Another source of uncertainty is personal identity: are we the product of our parentage, or the label that society bestows on us? Or is it possible to forge our own path? Many films touched on this, some mentioned (Meyerowitz, The Big Sick) and some not. Two in particular exemplified not only the question, but the loneliness inherent in not knowing.

I’ll admit, I wasn’t eager to watch Mudbound. Its setting and subject matter made me think I had it pegged. 1940’s, Deep South, generational struggle. I expected a harrowing portrait of Jim Crow-era racism — powerful, to be sure, but not particularly enjoyable. What I got instead of was a precise, plodding rumination on American identity, and the way World War II disrupted soldiers’ conception of self. Two men, Jamie (Garrett Hedlund) and Ronsel (Jason Mitchell), return from the war to a small Mississippi farm. Slavery is decades gone, but socioeconomic roles remain largely the same: Jamie’s brother owns the farm, Ronsel’s family works the land. As resentment grows between the families, neither man can shake the feeling that he is being misused; that the world he has observed to be so big, so multifaceted, strips this tiny one of its power. Jamie drinks away his dormant potential; Ronsel lashes out against social mores he sees as dated and dying. Like the best Jeff Nichols drama, Dee Rees’ lets us simmer in that discomfort; there’s a rhythm to the film’s dread, a warning in its Gothic grays and browns. It’s clear the center cannot hold, but all the telegraphing in the world can’t dampen the impact when it all goes to hell. Mudbound is a near-perfect drama, potent and unnervingly specific.

I’ll admit, I wasn’t eager to watch Mudbound. Its setting and subject matter made me think I had it pegged. 1940’s, Deep South, generational struggle. I expected a harrowing portrait of Jim Crow-era racism — powerful, to be sure, but not particularly enjoyable. What I got instead of was a precise, plodding rumination on American identity, and the way World War II disrupted soldiers’ conception of self. Two men, Jamie (Garrett Hedlund) and Ronsel (Jason Mitchell), return from the war to a small Mississippi farm. Slavery is decades gone, but socioeconomic roles remain largely the same: Jamie’s brother owns the farm, Ronsel’s family works the land. As resentment grows between the families, neither man can shake the feeling that he is being misused; that the world he has observed to be so big, so multifaceted, strips this tiny one of its power. Jamie drinks away his dormant potential; Ronsel lashes out against social mores he sees as dated and dying. Like the best Jeff Nichols drama, Dee Rees’ lets us simmer in that discomfort; there’s a rhythm to the film’s dread, a warning in its Gothic grays and browns. It’s clear the center cannot hold, but all the telegraphing in the world can’t dampen the impact when it all goes to hell. Mudbound is a near-perfect drama, potent and unnervingly specific.

***

Most years, I give one film the Stephen Isn’t As Snobby As People Think, Sometimes He Likes Things That People Actually Saw Award — aptly (and concisely!) titled to remind myself that great cinema isn’t limited to small-budget indies; that a behemoth franchise can be just as artful as a delicate awards-baity biopic. It’s hard to think of a more appropriate recipient than the bold, criminally-underseen Blade Runner 2049. Despite my negative introduction with Sicario (full review), Denis Villeneuve has gone on to become one of my favorite modern auteurs: be it the brash outrage of Incendes, the cool crypticism of Enemy, the riveting melodrama of Prisoners, or the dreamy impressionism of Arrival (full review), Villeneuve is a master of tonal control. He knows exactly what feeling he wants to instill in the viewer, and he instills it ruthlessly. And what is the legacy of Blade Runner if not a distillation of some gnawing feeling; an elevation of ambient texture as art form? Despite decades of fan arguments, the plot of Blade Runner is its least fascinating part. Far more interesting are the questions posed by its tone: what is life, what is humanity, what am I? In the face of all this spectacular, neon nothingness, what right does man have to be anything? If the original prods at the existential, Villeneuve’s sequel absolutely roars it. Zimmer and Wallfisch’s score shouts it; Deakins’ gorgeous cinematography overwhelms with it. It’s a difficult, strange reflection on personhood and the quest for meaning; one that never provides easy answers or tidy conclusions. Like the original, it’s a daring — and, from a studio perspective, laudably risky — cocktail of blockbuster grandeur and arthouse ambiguity. It’s also easily the best science fiction film of the year. An absolute stunner.

Most years, I give one film the Stephen Isn’t As Snobby As People Think, Sometimes He Likes Things That People Actually Saw Award — aptly (and concisely!) titled to remind myself that great cinema isn’t limited to small-budget indies; that a behemoth franchise can be just as artful as a delicate awards-baity biopic. It’s hard to think of a more appropriate recipient than the bold, criminally-underseen Blade Runner 2049. Despite my negative introduction with Sicario (full review), Denis Villeneuve has gone on to become one of my favorite modern auteurs: be it the brash outrage of Incendes, the cool crypticism of Enemy, the riveting melodrama of Prisoners, or the dreamy impressionism of Arrival (full review), Villeneuve is a master of tonal control. He knows exactly what feeling he wants to instill in the viewer, and he instills it ruthlessly. And what is the legacy of Blade Runner if not a distillation of some gnawing feeling; an elevation of ambient texture as art form? Despite decades of fan arguments, the plot of Blade Runner is its least fascinating part. Far more interesting are the questions posed by its tone: what is life, what is humanity, what am I? In the face of all this spectacular, neon nothingness, what right does man have to be anything? If the original prods at the existential, Villeneuve’s sequel absolutely roars it. Zimmer and Wallfisch’s score shouts it; Deakins’ gorgeous cinematography overwhelms with it. It’s a difficult, strange reflection on personhood and the quest for meaning; one that never provides easy answers or tidy conclusions. Like the original, it’s a daring — and, from a studio perspective, laudably risky — cocktail of blockbuster grandeur and arthouse ambiguity. It’s also easily the best science fiction film of the year. An absolute stunner.

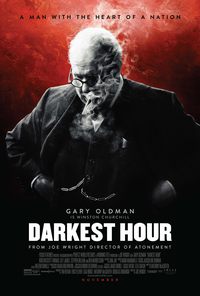

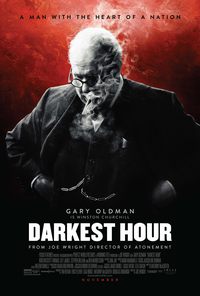

4. Crafting A Legacy: Only The Brave and Darkest Hour

If Danny Meyerowitz and Tonya Harding looked back this year, other protagonists were more inclined to look forward with an almost pre-emptive regret, feeling the weight of future hindsight. Two films, about as different in tone as can be, examine the legacy we leave in our response to hardship.

There are a few unpopular choices on this list. But if there’s one I’m most eager to go to bat for, it’s Only The Brave; the most heartrending — and woefully overlooked — biopic of the year. Following the rise and fall of the Granite Mountain Hotshots, the film does for wildfire fighting what Nightcrawler (full review) did for crime-scene photography or The Hurt Locker did for bomb disposal: it presents the stressors, and emotional contradictions, of a world I’d never really known existed. Unlike a Bigelow flick, though, what I loved about Only The Brave was how uncomplicated my sympathies were allowed to be. Firefighting may well be the purest symbol of human endurance: flawed men confronting an ever-present danger, with no agenda or motive in sight. The stakes are high, the enemy quite literally unforgiving, and the battle lines drawn vividly clear. While the film is framed around its tragic finale, it shines most brightly in its quiet aftermath — a meditation on grief, and the weight of survival, which communicates more emotional truth in five minutes than most war films do in their entire runtime. Impeccably brought to life by an all-star cast (Josh Brolin, Miles Teller, Jennifer Connelly, Jeff Bridges), it’s the most communal, cathartic movie-going experience I had in 2017. I cried. You’ll cry. In a year where nothing seems pure — no victory untainted by an ugly shift in power to exploit it, no hero without the spectre of some politicized enemy — when everything has a secondary and tertiary agenda, dear God, doesn’t it feel good to cry at simple, human bravery?

There are a few unpopular choices on this list. But if there’s one I’m most eager to go to bat for, it’s Only The Brave; the most heartrending — and woefully overlooked — biopic of the year. Following the rise and fall of the Granite Mountain Hotshots, the film does for wildfire fighting what Nightcrawler (full review) did for crime-scene photography or The Hurt Locker did for bomb disposal: it presents the stressors, and emotional contradictions, of a world I’d never really known existed. Unlike a Bigelow flick, though, what I loved about Only The Brave was how uncomplicated my sympathies were allowed to be. Firefighting may well be the purest symbol of human endurance: flawed men confronting an ever-present danger, with no agenda or motive in sight. The stakes are high, the enemy quite literally unforgiving, and the battle lines drawn vividly clear. While the film is framed around its tragic finale, it shines most brightly in its quiet aftermath — a meditation on grief, and the weight of survival, which communicates more emotional truth in five minutes than most war films do in their entire runtime. Impeccably brought to life by an all-star cast (Josh Brolin, Miles Teller, Jennifer Connelly, Jeff Bridges), it’s the most communal, cathartic movie-going experience I had in 2017. I cried. You’ll cry. In a year where nothing seems pure — no victory untainted by an ugly shift in power to exploit it, no hero without the spectre of some politicized enemy — when everything has a secondary and tertiary agenda, dear God, doesn’t it feel good to cry at simple, human bravery?

***

Darkest Hour is also framed around tragedy, but the two couldn’t be more different. Joe Wright’s portrait of Churchill-at-the-crossroads is a glorious, fist-pumping crescendo of a film; and the best treatment of Dunkirk to boot. Much has rightly been made of Gary Oldman’s transformative performance — he doesn’t just play Churchill, he becomes possessed by Churchill, with all the magnetism and arrogance and impulsivity that come with it. From beginning to end, this is his story to carry; his dark night of the soul and its roaring denoument. But it’d be a shame to forget how well everything works in concert to prop up Oldman’s portrayal. Skirting between the claustrophobic palace intrigue within ministry walls and the total, apolitical devastation without, the film lets us feel the weight of Dunkirk more than any Zimmer ticking clock: not just the incomparable cost of human life in the present, but the unforgiving gaze of a future that will remember and judge. It implicates us in Churchill’s struggle, in his terrible need to balance cold political calculus against hot-blooded passion. It reminds us that no decision of value is simple. That history may have smiled on Churchill’s bold stand, but with an alternate roll of the dice it could just as easily have damned him; that the line between courage and recklessness, between grand oration and warmongering hucksterdom, is often in the eye of the beholder. In a year brimming with populist bombast and rage-trumping-rationale, it might seem odd that Churchill’s rallying cry moved me like it did. I certainly don’t think the film idolizes him — nor do I think his take-no-prisoners style is best emulated today. Maybe it’s that in the face of overwhelming adversity, what he presented as the courage of his convictions was, in fact, the product of relentless self-reflection. That final speech on the Parliament floor isn’t powerful because Churchill stands alone, but because his verve — his passion — persuades the entire room to join him. Like the River City townspeople marching with Harold Hill, I don’t believe, in that moment, Winston’s flowery language has stripped them of their reservations. They’ve simply realized that it’s better to gamble on a shared answer than be divided on the question, if answer they must; better to suffer as one voice, to opt-in to a confidence they may never earn, than to quietly erode apart. That community, that bringing together of people, is — I believe — the true legacy Wright is grappling with. And it’s one that seems hopelessly out of reach today.

Darkest Hour is also framed around tragedy, but the two couldn’t be more different. Joe Wright’s portrait of Churchill-at-the-crossroads is a glorious, fist-pumping crescendo of a film; and the best treatment of Dunkirk to boot. Much has rightly been made of Gary Oldman’s transformative performance — he doesn’t just play Churchill, he becomes possessed by Churchill, with all the magnetism and arrogance and impulsivity that come with it. From beginning to end, this is his story to carry; his dark night of the soul and its roaring denoument. But it’d be a shame to forget how well everything works in concert to prop up Oldman’s portrayal. Skirting between the claustrophobic palace intrigue within ministry walls and the total, apolitical devastation without, the film lets us feel the weight of Dunkirk more than any Zimmer ticking clock: not just the incomparable cost of human life in the present, but the unforgiving gaze of a future that will remember and judge. It implicates us in Churchill’s struggle, in his terrible need to balance cold political calculus against hot-blooded passion. It reminds us that no decision of value is simple. That history may have smiled on Churchill’s bold stand, but with an alternate roll of the dice it could just as easily have damned him; that the line between courage and recklessness, between grand oration and warmongering hucksterdom, is often in the eye of the beholder. In a year brimming with populist bombast and rage-trumping-rationale, it might seem odd that Churchill’s rallying cry moved me like it did. I certainly don’t think the film idolizes him — nor do I think his take-no-prisoners style is best emulated today. Maybe it’s that in the face of overwhelming adversity, what he presented as the courage of his convictions was, in fact, the product of relentless self-reflection. That final speech on the Parliament floor isn’t powerful because Churchill stands alone, but because his verve — his passion — persuades the entire room to join him. Like the River City townspeople marching with Harold Hill, I don’t believe, in that moment, Winston’s flowery language has stripped them of their reservations. They’ve simply realized that it’s better to gamble on a shared answer than be divided on the question, if answer they must; better to suffer as one voice, to opt-in to a confidence they may never earn, than to quietly erode apart. That community, that bringing together of people, is — I believe — the true legacy Wright is grappling with. And it’s one that seems hopelessly out of reach today.

3. Love Is Dangerous: The Shape of Water and Call Me By Your Name

Be it hyper-stylized or subtly understated, cinema has a lot to say about romance. But in 2017, the nature of it feels…different. Gone are the soft-focus euphemisms, the delicate pans to a fogged up window. This year, love feels like a political act — a dangerous, mystifying thing. Brightly lit, tangible, defiant. Two films this year, each with similarly decadent color palettes but very different aims, sharpened love to a knife.

Whatever the word is for what Guillermo del Toro does with fables, The Shape Of Water (full review) might be the clearest argument for it. An early-60’s love story between a nonverbal cleaning woman and a monstrous fish creature, the film lends itself to plenty of dissonant comparisons (tons of Edward Scissorhands-era Burton, some Beauty and the Beast, a whole lot of Amélie, a dash of Hugo or Hail Cesar or even La La Land). In his hands, though, it’s a perfect mix of wild romanticism, gore, shock, sadness. The filmmaking is visually gorgeous: lush blues and greens, tactile, glistening, a camera that swoops and pirouettes between scenes like a synchronized swimmer. It’s brimming with character actors doing unabashedly over-the-top work, be it Sally Hawkins’ wonderful brightness as the wordlessly emotive Elisa, or Michael Shannon’s terrifying, nihilistic Strickland. After all, joy and terror are two sides of the same coin in del Toro’s universe. Sex and violence are treated with the same fairytale frankness as raindrops on the window or jiggling jello pies: shimmeringly physical, dense, technicolored, wet. That same childlike wonder which renders monsters as beautiful, renders hatred as bottomless, unmotivated, raw. A gay man’s advances are cruelly rebuked; a black couple is refused service at a counter; Strickland wields his power like a cattle prod, over any one or thing “God” saw to put beneath him. None of this is remotely subtle. But there’s something powerful about that simplicity, about casual miracles and cruelties existing in the same, unblinking frame. How do we respond to new, uncomfortable textures? Blackened fingers, slimy flippers, a bubbling bathtub, an outstretched palm. Do we close our eyes, shoo them; ban them from the light of our civilized romances? Or do we reach out, unfurling, and plunge?

Whatever the word is for what Guillermo del Toro does with fables, The Shape Of Water (full review) might be the clearest argument for it. An early-60’s love story between a nonverbal cleaning woman and a monstrous fish creature, the film lends itself to plenty of dissonant comparisons (tons of Edward Scissorhands-era Burton, some Beauty and the Beast, a whole lot of Amélie, a dash of Hugo or Hail Cesar or even La La Land). In his hands, though, it’s a perfect mix of wild romanticism, gore, shock, sadness. The filmmaking is visually gorgeous: lush blues and greens, tactile, glistening, a camera that swoops and pirouettes between scenes like a synchronized swimmer. It’s brimming with character actors doing unabashedly over-the-top work, be it Sally Hawkins’ wonderful brightness as the wordlessly emotive Elisa, or Michael Shannon’s terrifying, nihilistic Strickland. After all, joy and terror are two sides of the same coin in del Toro’s universe. Sex and violence are treated with the same fairytale frankness as raindrops on the window or jiggling jello pies: shimmeringly physical, dense, technicolored, wet. That same childlike wonder which renders monsters as beautiful, renders hatred as bottomless, unmotivated, raw. A gay man’s advances are cruelly rebuked; a black couple is refused service at a counter; Strickland wields his power like a cattle prod, over any one or thing “God” saw to put beneath him. None of this is remotely subtle. But there’s something powerful about that simplicity, about casual miracles and cruelties existing in the same, unblinking frame. How do we respond to new, uncomfortable textures? Blackened fingers, slimy flippers, a bubbling bathtub, an outstretched palm. Do we close our eyes, shoo them; ban them from the light of our civilized romances? Or do we reach out, unfurling, and plunge?

***

It might seem odd — maybe even offensive — to compare Call Me By Your Name (full review), a heartbreaking queer romance set in 1980’s Italy, to a fable about falling in love with a fish creature. But in an odd way, they complement each other extremely well. Both are lovingly-constructed, atmospheric period pieces. Both center around a forbidden, near-Platonic brand of love; one which frees its protagonist from repetitive cycles and offers a means of escape. Elisa and Elio both glide through the world to their own rhythm, filled with a passion so self-evident that their scenes of silent longing rank among the most powerful moments of the year. And the specific objects of their love (both mysterious, fantastical, and hopelessly out of reach) are only relevant to the degree that they teach them to move. Guadagnino, like del Toro, uses his lens to highlight the world’s irresistible physicality — the crisp relief of a dip in the lake, the warmth of a Mediterranean summer evening, the juiciness of a freshly-picked peach, the way skin seems to glimmer in the sunlight. The way things, plainly seen, can feel almost hedonistic; can compel in you an unshakable want. It’s a film about learning who you are and the things you choose to want, less coming-of-age than coming-of-body. About presence, persistence, and a life fully felt — be it the joy of love or the pain of its absence. Michael Stuhlbarg (a voice of quiet compassion in both films) gives a monologue that would melt the hardest of hearts, and Sufjan Stevens (reprising the sparsely plucked folk of Carrie and Lowell) contributes the best original songs of the year. But Timothée Chalamet, showing stunning emotional range in the third act, is the film’s true revelation. In a single, extended take, he embodies that same contradiction Stevens is wrestling with: “Oh, to see without my eyes the first time that you kissed me…How much sorrow can I take?…Blessed be the mystery of love.”

It might seem odd — maybe even offensive — to compare Call Me By Your Name (full review), a heartbreaking queer romance set in 1980’s Italy, to a fable about falling in love with a fish creature. But in an odd way, they complement each other extremely well. Both are lovingly-constructed, atmospheric period pieces. Both center around a forbidden, near-Platonic brand of love; one which frees its protagonist from repetitive cycles and offers a means of escape. Elisa and Elio both glide through the world to their own rhythm, filled with a passion so self-evident that their scenes of silent longing rank among the most powerful moments of the year. And the specific objects of their love (both mysterious, fantastical, and hopelessly out of reach) are only relevant to the degree that they teach them to move. Guadagnino, like del Toro, uses his lens to highlight the world’s irresistible physicality — the crisp relief of a dip in the lake, the warmth of a Mediterranean summer evening, the juiciness of a freshly-picked peach, the way skin seems to glimmer in the sunlight. The way things, plainly seen, can feel almost hedonistic; can compel in you an unshakable want. It’s a film about learning who you are and the things you choose to want, less coming-of-age than coming-of-body. About presence, persistence, and a life fully felt — be it the joy of love or the pain of its absence. Michael Stuhlbarg (a voice of quiet compassion in both films) gives a monologue that would melt the hardest of hearts, and Sufjan Stevens (reprising the sparsely plucked folk of Carrie and Lowell) contributes the best original songs of the year. But Timothée Chalamet, showing stunning emotional range in the third act, is the film’s true revelation. In a single, extended take, he embodies that same contradiction Stevens is wrestling with: “Oh, to see without my eyes the first time that you kissed me…How much sorrow can I take?…Blessed be the mystery of love.”

2. Haunted By Absence: A Ghost Story and Personal Shopper

The flipside of love is loss — or, more specifically, the vacuum left by love’s absence. Two films this year explored that particular ache: both sparse, impressionistic pieces which take that metaphorical haunting to unsettling extremes.

A Ghost Story is a difficult film to write about, because describing it in words seems antithetical to the point: a nameless couple, played by Rooney Mara and Casey Affleck, live together in a tiny plot in Texas until…well, until they don’t. Less feature film than elaborate art installation, David Lowery’s piece is a visual representation of grief turned inside-out. It’s a story not primarily of losing something but of becoming the thing that was lost, an object of orphaned love, unneeded and stuck. It’s about the way we bind ourselves to certain places and memories, dislodge ourselves within their walls; about that intangible substance whose presence turns a house into a home, and whose absence turns a home into a memorial. Or ruin. Or shrine. That little bit of ourselves — our love, or sorrow, or resentment — which seems to hang in the air a moment too long, to be soaked up by someone else or linger like a ghost. None of this is particularly easy to watch. It’s an extremely slow, virtually wordless, claustrophobic mood piece, whose meandering tone lulls you into a trance while lobbing just enough sparse jolts to keep you on your toes. But if it clicks into you, like it clicked into me, it becomes something more than mood; something jarring and recognizable, which I’ve never seen on film before. A Ghost Story is an emotional haunting; a distant sort of intimacy, so chilly it eventually feels like warmth.

A Ghost Story is a difficult film to write about, because describing it in words seems antithetical to the point: a nameless couple, played by Rooney Mara and Casey Affleck, live together in a tiny plot in Texas until…well, until they don’t. Less feature film than elaborate art installation, David Lowery’s piece is a visual representation of grief turned inside-out. It’s a story not primarily of losing something but of becoming the thing that was lost, an object of orphaned love, unneeded and stuck. It’s about the way we bind ourselves to certain places and memories, dislodge ourselves within their walls; about that intangible substance whose presence turns a house into a home, and whose absence turns a home into a memorial. Or ruin. Or shrine. That little bit of ourselves — our love, or sorrow, or resentment — which seems to hang in the air a moment too long, to be soaked up by someone else or linger like a ghost. None of this is particularly easy to watch. It’s an extremely slow, virtually wordless, claustrophobic mood piece, whose meandering tone lulls you into a trance while lobbing just enough sparse jolts to keep you on your toes. But if it clicks into you, like it clicked into me, it becomes something more than mood; something jarring and recognizable, which I’ve never seen on film before. A Ghost Story is an emotional haunting; a distant sort of intimacy, so chilly it eventually feels like warmth.

***

Scrawled notes left on a counter. Unkept promises. Routes you might have taken had you been anyone but yourself; others attempted, blocked by barriers you didn’t even know were there. That thought which felt so sturdy inside, only to evaporate in the space between utterance and impact. Bouncing dots on an iPhone screen, spooky action at a distance signifying real thumbs on real glass, abruptly vanishing and reappearing like a pulse till suddenly: words. Gray, motionless, cold. Information. All of the “meaning” with none of the dance.

Scrawled notes left on a counter. Unkept promises. Routes you might have taken had you been anyone but yourself; others attempted, blocked by barriers you didn’t even know were there. That thought which felt so sturdy inside, only to evaporate in the space between utterance and impact. Bouncing dots on an iPhone screen, spooky action at a distance signifying real thumbs on real glass, abruptly vanishing and reappearing like a pulse till suddenly: words. Gray, motionless, cold. Information. All of the “meaning” with none of the dance.

We’re all haunted by something. In Clouds of Sils Maria, Olivier Assayas’ lead is haunted by her own past — by a beauty and liveliness that can’t last forever, can’t simply be conjured back into existence by virtue of acting it out. In Personal Shopper, she’s haunted by everyone else; by a failure to connect, or a desire to become, or both. Sometimes that takes the form of a letter, a text message, a whisper of grief or rote transaction in a posh fashion boutique. Sometimes it’s a literal ghost materializing in frame. This film is best entered blind, so — like A Ghost Story — I don’t want to ruin much by way of exposition. All I’ll say is it’s an enigmatic ride in the best possible way: there are crescendos of magical realism which absolutely floored me, and questions brought up which I’m not sure I’ll ever resolve. Assayas’ direction is excellent, his mood-building is confident and on-point, and Kristen Stewart gives the second best performance of a Twilight star this year.

1. Signifying Nothing: Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri and Good Time

Love, loss, striving, regret…2017 was a year of complicated emotions. But if there was one universal mood which overwhelmed all others, it was this: a feeling of outrage — a desire to do something — with nowhere of value to funnel it. That impotent shout of “something is wrong, and I don’t know how to change it”, which belied countless headlines and jokes and exasperated Twitter rants. So it’s fitting that my two favorite films of the year chronicle the actions of deeply flawed people, as they try to redirect their fire and fury into something approaching good.

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (full review) may be the most mature film of Martin McDonagh’s career. It has all the cleverness, and gleeful blasphemy, of his earlier work — unquotable monologues, manic fits of disproportional violence. But it also has something serious to say, and is willing to take its brooding time saying it. In that sense, it’s hard not to compare it to his brother’s Calvary (full review). If Calvary asked the question “What use is faith in a world whose institutions fail to earn it?”, Three Billboards asks “What good is anger when there’s no one to absorb the blame?” It’s a story of characters filled with righteous indignation and no proper place to funnel it. Mildred Hayes can’t believe her daughter’s murder hasn’t been solved. Sgt Dixon can’t believe his boss’s “good” name is being dragged through the mud. In typical playwright fashion, improbably heightened events are used to tease out real emotions from real people: the point isn’t what happens, it’s how these characters would respond if it had. Perfectly scripted and wonderfully realized (Frances McDormand, Sam Rockwell, and Woody Harrelson all shine), those responses are a joy to witness. If you go in expecting an A-to-B storyline with lovable heroes, you’ll be sorely disappointed: this is a film where no one is righteous, no one is correct, and (contrary to popular controversy, I’d argue) no one comes within spitting distance of redemption. But they want to be redeemed, and that want — through the muck and darkness — is palpable. If you’re ready to soak in a few hours of gray, you’d be hard pressed to do better than this.

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (full review) may be the most mature film of Martin McDonagh’s career. It has all the cleverness, and gleeful blasphemy, of his earlier work — unquotable monologues, manic fits of disproportional violence. But it also has something serious to say, and is willing to take its brooding time saying it. In that sense, it’s hard not to compare it to his brother’s Calvary (full review). If Calvary asked the question “What use is faith in a world whose institutions fail to earn it?”, Three Billboards asks “What good is anger when there’s no one to absorb the blame?” It’s a story of characters filled with righteous indignation and no proper place to funnel it. Mildred Hayes can’t believe her daughter’s murder hasn’t been solved. Sgt Dixon can’t believe his boss’s “good” name is being dragged through the mud. In typical playwright fashion, improbably heightened events are used to tease out real emotions from real people: the point isn’t what happens, it’s how these characters would respond if it had. Perfectly scripted and wonderfully realized (Frances McDormand, Sam Rockwell, and Woody Harrelson all shine), those responses are a joy to witness. If you go in expecting an A-to-B storyline with lovable heroes, you’ll be sorely disappointed: this is a film where no one is righteous, no one is correct, and (contrary to popular controversy, I’d argue) no one comes within spitting distance of redemption. But they want to be redeemed, and that want — through the muck and darkness — is palpable. If you’re ready to soak in a few hours of gray, you’d be hard pressed to do better than this.

***

We’ve arrived at my favorite film of the year, and I’m largely at a loss for words — after all, what can constructively be said about alchemy? Good Time simply has no right to be as marvelous as it is. Following a young man (an electric, virtually unrecognizable Robert Pattinson) over a single evening in Queens as he attempts to make bail for his incarcerated brother, Good Time is pure, visceral cinema; putting you in the headspace of the unlikeliest protagonist. Pattinson’s Connie is about as far from a role model as any in Three Billboards. A high-octane control freak, the film opens with him removing his developmentally disabled brother from therapy — to rob a bank in broad daylight. When the job goes south and Nick winds up in Rikers, Connie uses every tool in his arsenal to free him. He breaks into the prison wing of a hospital. He tries to flip a Sprite bottle filled with LSD. He sweet talks his girlfriend for cash, a kindly older woman for her home, and her sixteen-year-old granddaughter for a midnight ride that will end in the backseat of a cop car. He pummels a security guard to within an inch of his life, and from all outward appearances he feels vindicated in doing so — sees casualties left in his wake as justified, uncomplicated. Why? Because Nick is family. He loves, and feels a holy responsibility towards, his brother, and all that fear and guilt and frustration combine into a righteous propulsion to act. Whether that action is helpful or harmful is almost irrelevant. The central image of the film is also its thesis: Connie, breathless, running for everything he’s worth, while the redblack night bends around him. Part Taxi Driver, part Linklater, and part Harmony Korine, Good Time is a breathless, neon-infused fever dream of a film. It’s mesmerizing, cathartic, daring, provocative. And it features, by far, the most powerful closing shot of the year: a quiet, gentle exhale after all the tension we’d endured. Leaving the theatre, I wasn’t sure how to characterize my feelings. I was wrestling with too many conflicted emotions. I still am.

We’ve arrived at my favorite film of the year, and I’m largely at a loss for words — after all, what can constructively be said about alchemy? Good Time simply has no right to be as marvelous as it is. Following a young man (an electric, virtually unrecognizable Robert Pattinson) over a single evening in Queens as he attempts to make bail for his incarcerated brother, Good Time is pure, visceral cinema; putting you in the headspace of the unlikeliest protagonist. Pattinson’s Connie is about as far from a role model as any in Three Billboards. A high-octane control freak, the film opens with him removing his developmentally disabled brother from therapy — to rob a bank in broad daylight. When the job goes south and Nick winds up in Rikers, Connie uses every tool in his arsenal to free him. He breaks into the prison wing of a hospital. He tries to flip a Sprite bottle filled with LSD. He sweet talks his girlfriend for cash, a kindly older woman for her home, and her sixteen-year-old granddaughter for a midnight ride that will end in the backseat of a cop car. He pummels a security guard to within an inch of his life, and from all outward appearances he feels vindicated in doing so — sees casualties left in his wake as justified, uncomplicated. Why? Because Nick is family. He loves, and feels a holy responsibility towards, his brother, and all that fear and guilt and frustration combine into a righteous propulsion to act. Whether that action is helpful or harmful is almost irrelevant. The central image of the film is also its thesis: Connie, breathless, running for everything he’s worth, while the redblack night bends around him. Part Taxi Driver, part Linklater, and part Harmony Korine, Good Time is a breathless, neon-infused fever dream of a film. It’s mesmerizing, cathartic, daring, provocative. And it features, by far, the most powerful closing shot of the year: a quiet, gentle exhale after all the tension we’d endured. Leaving the theatre, I wasn’t sure how to characterize my feelings. I was wrestling with too many conflicted emotions. I still am.

Outro…

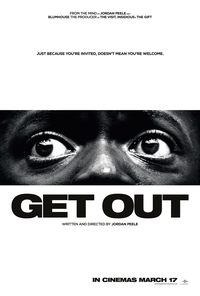

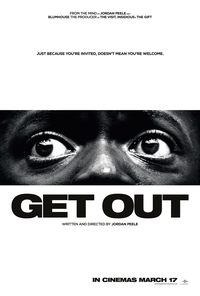

I think I’ve written enough for one year. But I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge how many excellent movies I still couldn’t cover. Of all the films I enjoyed this year (Dunkirk, Let It Fall, Logan, Columbus, Coco, Wonder Woman…) the one that really stands out, that I can’t believe still didn’t make this list, is Get Out. Honestly, has anything else left a comparable cultural footprint? If anything, I think that dent just makes some films too daunting to write about — it’s tough to find something new to say about a film that’s already permeated the Zeitgeist. And it felt reductive, somehow, to try and pair it with anything else on the list — as if I could lump the black experience with my own cheesy sentiments about 2017 by way of analogy. (The best I could come up with was Personal Shopper, and I’ll leave the hamfisted thematic parallels as an exercise to the reader…)

I think I’ve written enough for one year. But I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge how many excellent movies I still couldn’t cover. Of all the films I enjoyed this year (Dunkirk, Let It Fall, Logan, Columbus, Coco, Wonder Woman…) the one that really stands out, that I can’t believe still didn’t make this list, is Get Out. Honestly, has anything else left a comparable cultural footprint? If anything, I think that dent just makes some films too daunting to write about — it’s tough to find something new to say about a film that’s already permeated the Zeitgeist. And it felt reductive, somehow, to try and pair it with anything else on the list — as if I could lump the black experience with my own cheesy sentiments about 2017 by way of analogy. (The best I could come up with was Personal Shopper, and I’ll leave the hamfisted thematic parallels as an exercise to the reader…)

So, I’ll leave it at that: vague honorable mentions and as many disclaimers as I can muster. Jordan Peele is the man. Chris Nolan is a maniac. Patty Jenkins pulled off a miracle. Why can’t HBO shows count as movies? Wouldn’t The Deuce make a great companion piece to Good Time? Am I a monster for not adding The Florida Project (full review) to this list? Do you remember that year I didn’t add Mad Max (full review)? I’m wrong! I know I’m wrong! Why are you still reading this? Movies.

Brigsby Bear is nearly impossible to explain without giving away its central premise, and that premise may be its most delightful aspect. Part Room and part The Disaster Artist, it’s the story of a man (Kyle Mooney) who has only seen a single television show: a cheesy, dated, Barney-esque educational series named “Brigsby Bear.” Stranger still, he’s the only one who’s seen it. So when circumstances arise which permanently take the show off the air, he feels an odd sort of weight — this thing was his, and now it’s gone, and no else is even aware of its absence. He copes with this loss the only way he knows how: by making more episodes. Donning an enormous bear mask and a Public Access-worthy collection of props, James and his friends recreate the bewildering universe of Brigsby. It’s a movie about how entertainment gives color and texture to our world; how consuming it lets us escape from life’s difficulties, and how creating it lets us transform them into joy. The cast is uniformly great, but the true standout is Mark Hamill, giving his best turn as a knowledge-bestowing hermit this year — The Last what, now? One the pleasant surprises of 2017.

Brigsby Bear is nearly impossible to explain without giving away its central premise, and that premise may be its most delightful aspect. Part Room and part The Disaster Artist, it’s the story of a man (Kyle Mooney) who has only seen a single television show: a cheesy, dated, Barney-esque educational series named “Brigsby Bear.” Stranger still, he’s the only one who’s seen it. So when circumstances arise which permanently take the show off the air, he feels an odd sort of weight — this thing was his, and now it’s gone, and no else is even aware of its absence. He copes with this loss the only way he knows how: by making more episodes. Donning an enormous bear mask and a Public Access-worthy collection of props, James and his friends recreate the bewildering universe of Brigsby. It’s a movie about how entertainment gives color and texture to our world; how consuming it lets us escape from life’s difficulties, and how creating it lets us transform them into joy. The cast is uniformly great, but the true standout is Mark Hamill, giving his best turn as a knowledge-bestowing hermit this year — The Last what, now? One the pleasant surprises of 2017. Is there a more consistent filmmaker in Hollywood than Edgar Wright? Love him or leave him, his movies always deliver on precisely what their trailers promise. Hell, they’re effectively feature-length trailers: razor-sharp edits, rip-roaring soundtracks, and quotable quips delivered by genre-fied characters who (impossibly) earn them. If Scott Pilgrim proved the formula, Baby Driver might prove its hypothetical limit: it’s a deliriously fun joyride through style over substance, with style approaching infinity and substance zero. Ansel Elgort’s Baby acts as an audience surrogate, driving his getaway car to the rhythm of a non-stop classic rock playlist. Inseparable from his headphones, Baby is most at peace when he’s drowning in stimulation. Cars skid, cameras veer, and a star-studded cast chews diesel-drenched set dressing while Queen and Blur blare triumphant. If Brigsby Bear was the best film about escape, Baby Driver might be the best example of it: pure, cinematic joy.

Is there a more consistent filmmaker in Hollywood than Edgar Wright? Love him or leave him, his movies always deliver on precisely what their trailers promise. Hell, they’re effectively feature-length trailers: razor-sharp edits, rip-roaring soundtracks, and quotable quips delivered by genre-fied characters who (impossibly) earn them. If Scott Pilgrim proved the formula, Baby Driver might prove its hypothetical limit: it’s a deliriously fun joyride through style over substance, with style approaching infinity and substance zero. Ansel Elgort’s Baby acts as an audience surrogate, driving his getaway car to the rhythm of a non-stop classic rock playlist. Inseparable from his headphones, Baby is most at peace when he’s drowning in stimulation. Cars skid, cameras veer, and a star-studded cast chews diesel-drenched set dressing while Queen and Blur blare triumphant. If Brigsby Bear was the best film about escape, Baby Driver might be the best example of it: pure, cinematic joy. On its surface, The Big Sick is just about about as heartfelt a love story as you can get. And as a lover of standup, and a particular fan of Kumail and Emily’s, I fully expected it to move me. I just hadn’t anticipated why it’d move me. In heavier hands, the story might have written itself: love beset by tragedy, humor as a bulwark against hopelessness, light at the end of the blah blah blah credits. It would have tugged heartstrings, and it would have been earned. But The Big Sick foregoes tugging for a more precise operation, revealing tiny layers of truth behind the bleeding-heart drama. Truths about growing up and finding your voice; about the burden of family and religion and culture, and the delicate maneuver of “breaking free” without severing or diminishing their weight. It’s about the changes Emily demands of Kumail by virtue of her existence: her refusal to be sidelined, to be swept under the rug of “private life” to an overbearing family; the way she forces him to reckon with his own identity and worth. It’s about how guarded passivity strains our relationships, and uncompromising honesty becomes its own higher brand of love — messy, hurtful, and wholly undivided. Avoid spoilers if you want; this isn’t, ultimately, about a meet-cute or coma. Those are handled beautifully, but there’s a deeper healing (and awakening) at play.