In our 2014 recap, I left my #6 slot reserved for the “Dallas Buyers’ Club Award”: a conventional, non-boundary-pushing narrative that manages to blow you away by sheer consistency. Nightcrawler won out, though Gone Girl (like most David Fincher projects) probably fit the bill better. Zodiac is the patron saint of the genre.

It’s probably not a coincidence that all of those movies are about some form of journalism. More specifically, they’re about the process by which Truth becomes Story; it might be distorted (Nightcrawler), sensationalized (Gone Girl), or obsessively constructed (Zodiac), but there’s always some mechanism at play. Sometimes the mechanism is subtext, an invisible hand that toys with characters’ lives. Here, the mechanisms are the true characters.

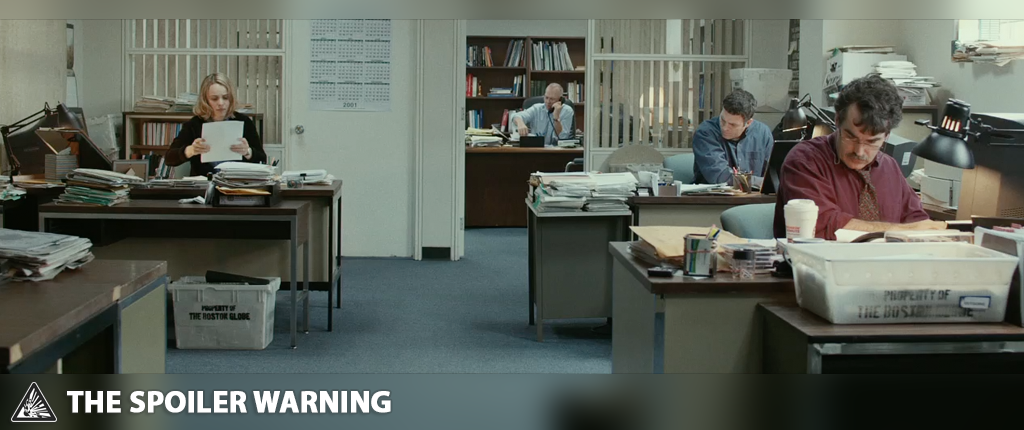

First is the protagonist: patient, level-headed, good-old-fashioned reporting. In 2001, an investigative branch of Boston Globe (“Spotlight”) was assigned to cover allegations of molestation in the local Catholic church. For a subject ripe for melodrama, the film that chronicles it is refreshingly understated. The horror of the story is rarely the focus — we already know the ending, and are living the epilogue. Spotlight is about the mechanics behind that story. It’s about how Rachel McAdams subtly calibrates her interview style to calm a nervous subject; how Michael Keaton pivots between boys’-club chumminess and disarming directness; how Mark Ruffalo looks up from his notepad to repeat an interviewee’s name, giving just enough eye-contact to convey sympathy while respecting his bruised, stoic ego; why Liev Schreiber chooses to stall publication long after HuffPo would have waged a clickbait culture war. It’s about characters setting aside drama to do their job; phenomenally acted to the point of being invisible.

Which isn’t to say it sidesteps the difficult questions; like Calvary, Spotlight has plenty to say about faith and disillusionment. But it’s never framed as a “gotchya” moment or lazy Religulous-esque indictment. The antagonist, if there is one, isn’t a specific villain. And despite characters’ repeated urges to “focus on the system”, I don’t think it’s a specific organization either — not even the obvious one at the center. It’s any system which discourages self-criticism, and any hierarchy which puts undue trust in its leaders. The Catholic Church, of course, is guilty. But so is Boston itself, whose members and media repeatedly looked the other way in the name of community pride. I couldn’t help but be reminded of Penn State, and the way collective hope — be it in God or the Home Team — can smother individual unease. Grand, dramatic conviction has the power to blind, and only a measured response can expose it. The two reasons no one trusts Schreiber are actually one: he’s a Jew and he doesn’t like baseball.

I really enjoyed this movie. Chris and I unpack it in this week’s episode.