Somewhere around the halfway mark of Mistress America, college freshman Tracy offers notes on her friend’s writing style. [Paraphrased:] “You write about people who are so free and fun. But it’s obvious that you aren’t one of those people, and that’s awkward.”

I’m a pretty enthusiastic Noah Baumbach fan, but if ever there were an apt description of his weakness, Tracy’s might be it. I only truly believe his dialogue when it’s spoken by navel-gazing intellectuals — unhappy, uncomfortable, male. His recent Muse, Greta Gerwig, plays none of those things; the Annie to Baumbach’s Alvy, her characters are energetic, free-spirited, and disarmingly at ease. They’re everything Jesse Eisenberg isn’t. So if Squid and the Whale was an exercise in brutal realism, the overwhelming vibe of Frances Ha was wistful rhapsody, an ode to some unattainable, romantic ideal. Frances talks like nobody actually talks. And we don’t necessarily identify with her, so much as we want to be rescued by her.

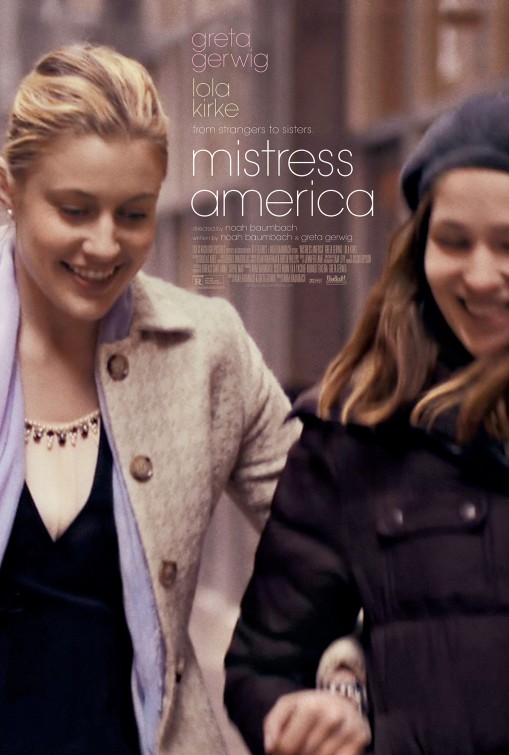

In Mistress America, everyone talks the way nobody talks, and it’s clear they can’t rescue a thing. Tracy is an English major struggling to find her feet, lost in a world without a manual. Her older “sister” Brooke is a Platonic Ideal of Manic Pixie Womanhood: she lives in Times Square, sings with the Dirty Projectors, teaches aerobics and tutors algebra and but also is trying to open a restaurant. As Brooke proudly imparts wisdom to Tracy, the dialogue is literally unbelievable — a mess of non sequitors and too-“witty” retorts, interjections so clean you can practically hear the em dashes. Pure, theatrical screwball.

As the film progresses, that “screwball” dial gets cranked to a hilarious 11. Characters consult psychics. An aristocrat gives a performative monologue and fashions an apple bong. Eventually it culminates in an ensemble-bursting argument which feels less like a movie than a zany high school play: if a Duchess had marched in shouting about blintzes, no one would bat an eye. The nature of the massive argument? Tracy has co-opted Brooke’s life for a character in one of her stories. The problem? It’s a one-dimensional caricature. It paints women as shallow and irresponsible. It condescends, even if it means to rhapsodize. Tennessee Williams’ plays were inspired by real people too, but Brooke “isn’t friends with fucking Tennessee Williams.”

She’s not. But I can think of at least one director she is close with, and a film that feels a helluvalot like a play. And while all the mayhem adds up to more of a wink than a thesis, it’s surprisingly fun to watch her caricature explode.

(For more thoughts on Noah Baumbach, see my review of While We’re Young)