They might need to invent a new word for what Guillermo del Toro does. His films are dark, provocative fables; mature themes coated in a childlike sheen. All the starry-eyed unsubtlety of a saccharine Disney flick cut with something which isn’t bitter so much as menacing and strange. Black roses blooming in a graveyard; a drop of blood in a sugarcube.

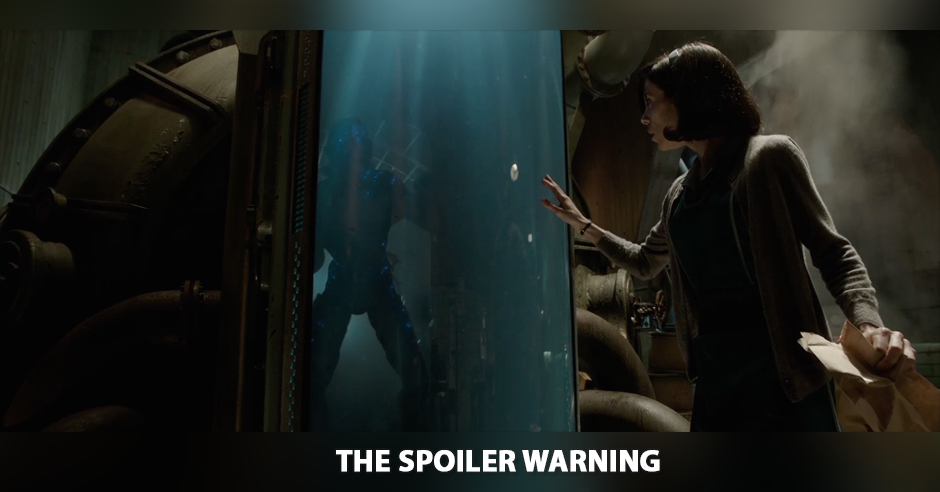

Whatever the word is, The Shape Of Water might be the clearest argument for it. An early-60’s love story between a nonverbal cleaning woman and a monstrous fish creature, del Toro’s latest lends itself to plenty of dissonant comparisons (tons of Edward Scissorhands-era Burton, some Beauty and the Beast, a whole lot of Amélie, a dash of Hugo or Hail Cesar or even La La Land). In his hands, though, it’s a perfect mix of wild romanticism, gore, shock, sadness. The filmmaking is visually gorgeous: lush blues and greens, tactile, glistening, a camera that swoops and pirouettes between scenes like a synchronized swimmer. It’s brimming with character actors doing unabashedly over-the-top work. Sally Hawkins’ emotive Elisa is the clear standout, but so is Richard Jenkins’ lonely artist Giles, Michael Stuhlbarg’s conflicted scientist Hoffstetler, Octavia Spencer’s no-nonsense Zelda. Michael Shannon is…well, I don’t know what the hell he’s doing, exactly, but I know that it’s terrifying. After all, romance and terror are two sides of the same coin in del Toro’s universe. Sex and violence are treated with the same fairytale frankness as raindrops on the window or jiggling jello pies: shimmeringly physical, dense, technicolored, wet. That same childlike wonder which renders monsters as beautiful, renders hatred as bottomless, unmotivated, raw. A gay man’s advances are cruelly rebuked; a black couple are refused service at a counter; Shannon’s Strickland wields his power like a cattle prod, over any one or thing “God” saw to put beneath him. None of this is remotely subtle. But there’s something powerful about that simplicity, about casual miracles and cruelties existing in the same, unblinking frame. How do we respond to new, uncomfortable textures? Blackened fingers, slimy flippers, a bubbling bathtub, an outstretched palm. Do we close our eyes, shoo them; ban them from the light of our soundstages, fables, and civilized dining establishments? Or do we reach out, unfurling, and plunge?

Chris, the ghost of Carson future, and I review it on this week’s episode: