tl;dr: here’s a list with no explanations

Things I wanted to see but hadn’t yet: Mustang (Update: Review Here, almost certainly would have made my list), Son of Saul (Update: Review Here, also list-worthy), Heart of a Dog, Phoenix, Victoria, Amy, Steve Jobs, Trumbo, Buzzard

You can hear my friends and I discuss our lists at The Spoiler Warning Podcast. You can also find more reviews at my Letterboxd page. Here’s a link to last year’s list.

Intro I Always Feel Compelled To Write For Some Reason

Every year since…2008?…I’ve shown up on The Spoiler Warning to make a Top X Films Of The Year list. In the early days it was typically a no-brainer. On a good year I might have seen 15 movies, 5 of which I’d actively dislike. Whittling it down to a Top 5 yielded easy, if predictably college-dude results: The Dark Knight, Up In The Air, Inglorious Basterds, Inception.

Now on a reasonable year I’ll catch 75 movies, with maybe half being quote critically acclaimed endquote. Needless to say, this list-making thing has become a lot more challenging. Gone are the days where I could slap a gold medal on the latest Nolan flick and move on. I’ve begun to recognize that A) there are so many good, worthwhile movies out there, and B) not all varieties of “good, worthwhile” are created equal in my mind. The more I watch and discuss film, the more I need to carve out my own unique value system: of all the good and worthwhile things, what do I most value?

This year I became convinced that I am not Big Spectacle Guy. There is one movie notably absent from this list, and it rhymes with Schmad Schmax. I can’t fault it. It did everything right. It was an overwhelming, masterful distillation of an auteur’s vision. It was big and spectacular, and I am simply not Spectacle Guy. Instead I’m embracing that the thing I care about, above all else, is what a movie says and how well it convinces me to listen. In a world overrun with stimuli, I’ve found myself (often unconsciously) digging for messages: how is the filmmaker using his/her platform and what does it instill in me? It doesn’t need to teach me something new, per se, but it should illuminate some (literal or emotional) truth. These are not the only kind of movies, nor do I subscribe to some snobby belief that they’re objectively better. But they are mine.

Looking over my list, I see not only a plethora of messages, but a trend in the type of message: namely, the blurry line between good and evil, high and low. Some films on my list are about the danger of blatant “heroes” and the virtue of modest, quiet persistence. Others give hate, ignorance, or depravity a human face. Others toy with the very idea of a distinction, convincing us to root for one character only to switch “teams” in the final act, or to put faith in a savior only to end with an anticlimactic thud. All of them convince me that generalizations are lazy; that truth is messy and takes serious work.

This is meant to be a Top 10 of sorts. 1-5 are straightforward, Best Of material. 6-10 are named awards, each with a winner and runners up. There the order is ill-defined at best. Is my runner up for #7 better than my runner up for #8? Is it genuinely “worse” than my top choice for #10? I have absolutely no idea. I loved them all. Let’s just get to the movies.

1-5: The “Best Of”

1. Anomalisa

Typically my #1 pick is set in stone months before these lists get made. So maybe I’m crazy for picking Anomalisa (full review), a movie I only had about 48 hours to wrestle with before recording. But I’ve got to go with my gut on this. Charlie Kaufman’s heartfelt, hilarious, deeply odd little film struck all the right chords. In a sense, this is the perfect complement to The End of the Tour (full review): it’s a story of why day-to-day existence is so damn hard — not due to grand suffering *cough*Revenant*cough* but due to sheer monotony. And in its own, subtle way, it’s a testament to why that monotony is beautiful. It has the best dialogue of the year, a breathtaking visual style that would put Pixar to shame, and possibly the most tender sex scene I’ve seen in my life. Oh, did I mention they’re all puppets? Laugh if you want, but this is as far from Team America as it gets. It’s beautiful, human, and true.

Typically my #1 pick is set in stone months before these lists get made. So maybe I’m crazy for picking Anomalisa (full review), a movie I only had about 48 hours to wrestle with before recording. But I’ve got to go with my gut on this. Charlie Kaufman’s heartfelt, hilarious, deeply odd little film struck all the right chords. In a sense, this is the perfect complement to The End of the Tour (full review): it’s a story of why day-to-day existence is so damn hard — not due to grand suffering *cough*Revenant*cough* but due to sheer monotony. And in its own, subtle way, it’s a testament to why that monotony is beautiful. It has the best dialogue of the year, a breathtaking visual style that would put Pixar to shame, and possibly the most tender sex scene I’ve seen in my life. Oh, did I mention they’re all puppets? Laugh if you want, but this is as far from Team America as it gets. It’s beautiful, human, and true.

2. Ex Machina

As an AI researcher who also loves movies, there probably hasn’t been a film more tailor-made for me than Ex Machina (full review)…with the possible exception of Her. But while Her had Spike Jonze, Joaquin Phoenix, and the promise of sappy indie tears (my three favorite things), this had nothing to foreshadow its greatness. If anything, I went in dreading an overly-serious bit of pseudointellectual fluff. But I can’t stress how quickly it won me over, how flawless it is in every aspect. It works as a genuinely compelling think-piece, a brooding thriller, a gnawing drama, and a spectacle all at once. Perhaps most importantly, it’s clever enough to know when to hold back on the specifics, to ground itself more in emotion than in imagined “facts.” To me this is Hollywood at its best; phenomenally acted, beautifully textured, thought-provoking, exhilarating, and crowd-pleasing to boot. If you’re wondering why Oscar Isaac, Alicia Vikander, and Domnhall Gleason seem to be exploding this year, let this film be your primer.

As an AI researcher who also loves movies, there probably hasn’t been a film more tailor-made for me than Ex Machina (full review)…with the possible exception of Her. But while Her had Spike Jonze, Joaquin Phoenix, and the promise of sappy indie tears (my three favorite things), this had nothing to foreshadow its greatness. If anything, I went in dreading an overly-serious bit of pseudointellectual fluff. But I can’t stress how quickly it won me over, how flawless it is in every aspect. It works as a genuinely compelling think-piece, a brooding thriller, a gnawing drama, and a spectacle all at once. Perhaps most importantly, it’s clever enough to know when to hold back on the specifics, to ground itself more in emotion than in imagined “facts.” To me this is Hollywood at its best; phenomenally acted, beautifully textured, thought-provoking, exhilarating, and crowd-pleasing to boot. If you’re wondering why Oscar Isaac, Alicia Vikander, and Domnhall Gleason seem to be exploding this year, let this film be your primer.

3. The Overnighters

This one is a cheat however you slice it, since it was clearly released in 2014. But it didn’t hit VOD until 2015, and if Rotten Tomatoes is any indication, that was many critics’ first introduction to it. It was certainly mine, and I was floored.

This one is a cheat however you slice it, since it was clearly released in 2014. But it didn’t hit VOD until 2015, and if Rotten Tomatoes is any indication, that was many critics’ first introduction to it. It was certainly mine, and I was floored.

There’s not much to say about The Overnighters (full review) that I haven’t already said. Documentaries tend to move me by exploring something big, shocking, or overwhelmingly tragic. This did the opposite, showcasing the power of the format to depict the small, intimate, and human. It follows a pastor in a small town in North Dakota, where a massive spike in low-income immigration has provoked a moral crisis. As a pastor, he believes it his duty to help any neighbor in need, and opens the church grounds for homeless men to sleep in. But as a pastor of a specific congregation, he also needs to keep the peace — and his congregants are far from comfortable with opening up their “home.” In keeping with my theme, there are no explicit good guys or bad guys here; just regular people, full of faith and conviction and (often misguided) fears. It’s artfully shot and utterly relevant in the current political Zeitgeist. If you have a religious upbringing, a heart for social justice, or even just liked Show Me A Hero (full review), I’d urge you catch this on Netflix immediately.

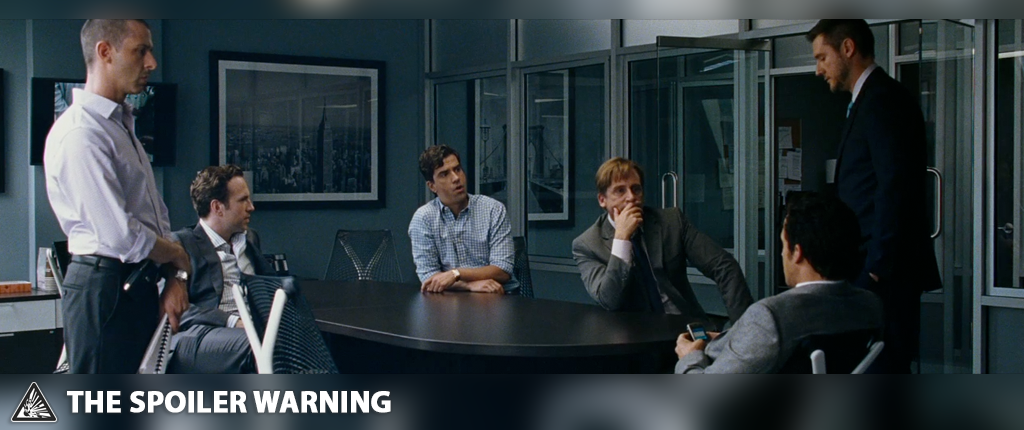

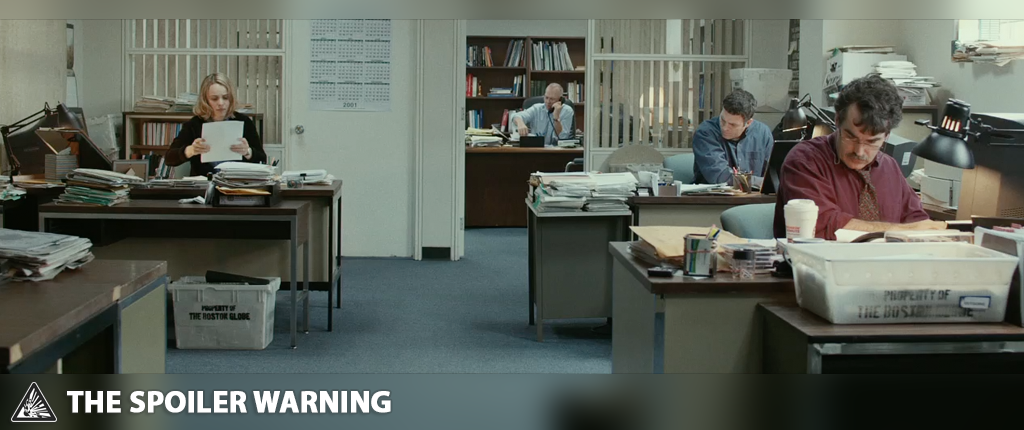

4. Spotlight

When I reviewed Mad Max: Fury Road I described it as a sort of gourmet bacon; a crowd-pleasing joyride so excessive that its very excess became a virtue. I couldn’t believe how fresh, how shocking straightforward muchness could be. In a similar vein, Spotlight (full review) might be compared to gourmet toast and black coffee. White bread, decaf. This is an ode to level-headed restraint, a film which resists excess at every turn. It’s a fantastic ensemble piece without a single showy performance. An urgent exposé on a horrifying subject, whose primary refrain is “let’s not rush this.” An utterly riveting drama about refusing to get caught up in drama. A wonderfully directed, meticulously constructed film that never calls attention to its craft. It’s so quiet, so subtle, so totally devoid of Oscar moments, yet somehow it’s also the perfect Oscar movie. And it carries a timely message: dramatic conviction has the power to blind, and only a measured response can expose it. In a world of tweet storms and clickbait journalism, the highest virtue just might be boring, unsexy patience.

When I reviewed Mad Max: Fury Road I described it as a sort of gourmet bacon; a crowd-pleasing joyride so excessive that its very excess became a virtue. I couldn’t believe how fresh, how shocking straightforward muchness could be. In a similar vein, Spotlight (full review) might be compared to gourmet toast and black coffee. White bread, decaf. This is an ode to level-headed restraint, a film which resists excess at every turn. It’s a fantastic ensemble piece without a single showy performance. An urgent exposé on a horrifying subject, whose primary refrain is “let’s not rush this.” An utterly riveting drama about refusing to get caught up in drama. A wonderfully directed, meticulously constructed film that never calls attention to its craft. It’s so quiet, so subtle, so totally devoid of Oscar moments, yet somehow it’s also the perfect Oscar movie. And it carries a timely message: dramatic conviction has the power to blind, and only a measured response can expose it. In a world of tweet storms and clickbait journalism, the highest virtue just might be boring, unsexy patience.

5. Carol

If I were to describe Carol (full review) in one word, it would be “hypnotic.” It is, in many respects, the dessert to Spotlight’s just-the-basics meal; lushly textured filmmaking where every frame is meant to be savored. This is the perfect episode of Mad Men, and like Mad Men, synopses are misleading at best. Carol isn’t about what it was, but how it felt to be there. A lesbian romance set in 50’s New York, the film is billed as a heartbreaking tale of Forbidden Love a la Brokeback Mountain. And while it works on that level, it most resonated with me as a meditation on the feeling of being lost, and the paradoxes inherent in finding yourself. Carol is the victim of a repressive sort of glamor, but that same glamor is what draws us to her. Therese is yearning to escape her do-as-you’re-told life, but her ultimate freedom comes from being helplessly swept up in someone else. Gorgeous cinematography and perfect acting aside, I can’t fully rationalize my love of Carol alongside some of these “weightier” choices. And maybe that’s the point. Sometimes you just need to be swept up in something.

If I were to describe Carol (full review) in one word, it would be “hypnotic.” It is, in many respects, the dessert to Spotlight’s just-the-basics meal; lushly textured filmmaking where every frame is meant to be savored. This is the perfect episode of Mad Men, and like Mad Men, synopses are misleading at best. Carol isn’t about what it was, but how it felt to be there. A lesbian romance set in 50’s New York, the film is billed as a heartbreaking tale of Forbidden Love a la Brokeback Mountain. And while it works on that level, it most resonated with me as a meditation on the feeling of being lost, and the paradoxes inherent in finding yourself. Carol is the victim of a repressive sort of glamor, but that same glamor is what draws us to her. Therese is yearning to escape her do-as-you’re-told life, but her ultimate freedom comes from being helplessly swept up in someone else. Gorgeous cinematography and perfect acting aside, I can’t fully rationalize my love of Carol alongside some of these “weightier” choices. And maybe that’s the point. Sometimes you just need to be swept up in something.

6-10: Awards: Winners and (Noteworthy) Runners Up

6. Stephen Isn’t As Snobby As Commenters Say He Is, Sometimes He Likes Stuff People Actually Saw Award: The Martian, w/ Inside Out and Creed

If you were to take this list at face value, you’d probably get the sense that “artsy fartsy” is the sole genre I enjoy. And while I do love me some independent cinema, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the huge number of great, big-budget crowdpleasers that came out this year. This is by no means an exhaustive list (see: Furious 7 (full review), Spy, The Walk (full review)), but I wanted to highlight the three most pleasant surprises. Inside Out is the first great Pixar movie in five years, and arguably the best in longer. Blending the secret-society-hiding-in-plain-sight joy of their vintage classics with the human-centric emotions of their later output, it perfectly encapsulates the Pixar mantra — an unabashedly childish movie about putting away childish things. Creed is a phenomenal underdog story in every sense of the word; in no universe did I expect the 7th Rocky sequel to put up a fight. But Ryan Coogler’s electrifying direction and Michael B. Jordan’s charismatic performance revitalized a tired franchise and delivered an absolute knock-out.

If you were to take this list at face value, you’d probably get the sense that “artsy fartsy” is the sole genre I enjoy. And while I do love me some independent cinema, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the huge number of great, big-budget crowdpleasers that came out this year. This is by no means an exhaustive list (see: Furious 7 (full review), Spy, The Walk (full review)), but I wanted to highlight the three most pleasant surprises. Inside Out is the first great Pixar movie in five years, and arguably the best in longer. Blending the secret-society-hiding-in-plain-sight joy of their vintage classics with the human-centric emotions of their later output, it perfectly encapsulates the Pixar mantra — an unabashedly childish movie about putting away childish things. Creed is a phenomenal underdog story in every sense of the word; in no universe did I expect the 7th Rocky sequel to put up a fight. But Ryan Coogler’s electrifying direction and Michael B. Jordan’s charismatic performance revitalized a tired franchise and delivered an absolute knock-out.

If ever there were a blockbuster with my name on it, though, The Martian (full review) would be it. The AV Club’s A.A. Dowd perfectly described it as the secular God’s Not Dead. This is an intoxicatingly optimistic, joyous celebration of the drug of problem solving, far less concerned with making converts than preaching to the choir of addicts — of whom I happily count myself a member. There’s nothing subtle or edgy about it. Mark Watney is a stand in for our geekiest aspirations, rummaging through his inventory to solve a real life point-and-click adventure game. That it works so well is largely a testament Damon’s overwhelming star power. But it’s also evidence of Ridley Scott’s timeless ability to mesmerize…Exodus notwithstanding. Make fun of the Hollywood Foreign Press all you want, but this made me laugh more than any so-called “comedy” of 2015. Until they make a separate category for Most Delightful, I’ll consider that Globe well-deserved.

7. The Act of Killing Award: The Look of Silence, w/ Cartel Land

It’s been a particularly excellent year for vital, hard-hitting documentaries. Cartel Land may, in fact, be the hardest-hitting of the bunch. Like Sicario (full review) it examines the reciprocal nature of the drug war, but to its infinite credit, it never succumbs to the pitfall of mistaking brooding vagueness for a point. With unprecedented access, the camera follows both the cartel and the morally-questionable vigilantes that fight it. Bullets fly. Heroes turn to villains before our eyes. And if at times it felt a bit voyeuristic, the truth on display was always mind-boggling.

It’s been a particularly excellent year for vital, hard-hitting documentaries. Cartel Land may, in fact, be the hardest-hitting of the bunch. Like Sicario (full review) it examines the reciprocal nature of the drug war, but to its infinite credit, it never succumbs to the pitfall of mistaking brooding vagueness for a point. With unprecedented access, the camera follows both the cartel and the morally-questionable vigilantes that fight it. Bullets fly. Heroes turn to villains before our eyes. And if at times it felt a bit voyeuristic, the truth on display was always mind-boggling.

Some truths run deeper than others, though, and none were as revelatory as those in Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Look of Silence (full review). A follow-up to the eponymous Act of Killing (full review), it aims to give the Indonesian genocide a human face. Where Killing chose the face of evil, though, Silence turns its attention to the innocent. We follow Adi as he interviews the very people who tore his family apart: the man who murdered his brother, the official who reaped the profits, the cowardly uncle who guarded his cell. At once unflinching and artfully subdued, it has no interest in soliciting easy, throwaway sympathy. Adi isn’t seeking pity, he’s searching for a way forward. And redemption can be far more complicated than grief.

8. Dallas Buyers Club Award: Love and Mercy, w/ Brooklyn

Two years ago I awarded my number one slot to a traditional, not-particularly-showy movie which blew me away by sheer consistency: Dallas Buyers Club. While I’ve since recanted that choice, I do think there’s room on any list for wonderfully-executed, basic filmmaking. Sometimes a great biopic, or a great romance, can stick with you longer than any “challenging” think piece. Brooklyn is one such film. A coming-of-age story set in 50’s New York, it might be the most gorgeously sentimental film of the year. Saoirse Ronan gives a star-making performance as Irish immigrant Eilis, but the supporting turns (particularly Emory Cohen) are no less endearing. As a romance it falls a bit short of masterful, but as an ode to the immigrant experience it floored me. If it hit a single wistful note, though, Love and Mercy hit about 50 in unison. Was it a Brian Wilson biopic? An off-putting romance? A story about creativity and mental illness, or about captivity and exploitation? Or was it just a simple ode to the thrill of making music, and an excuse to turn a timeless album into a soundtrack? I can’t label it. But while some notes (the Cusack / Banks romance) felt discordant and others (Dano in the Pet Sounds studio) transcendent, there was something seriously moving in the cacophony.

Two years ago I awarded my number one slot to a traditional, not-particularly-showy movie which blew me away by sheer consistency: Dallas Buyers Club. While I’ve since recanted that choice, I do think there’s room on any list for wonderfully-executed, basic filmmaking. Sometimes a great biopic, or a great romance, can stick with you longer than any “challenging” think piece. Brooklyn is one such film. A coming-of-age story set in 50’s New York, it might be the most gorgeously sentimental film of the year. Saoirse Ronan gives a star-making performance as Irish immigrant Eilis, but the supporting turns (particularly Emory Cohen) are no less endearing. As a romance it falls a bit short of masterful, but as an ode to the immigrant experience it floored me. If it hit a single wistful note, though, Love and Mercy hit about 50 in unison. Was it a Brian Wilson biopic? An off-putting romance? A story about creativity and mental illness, or about captivity and exploitation? Or was it just a simple ode to the thrill of making music, and an excuse to turn a timeless album into a soundtrack? I can’t label it. But while some notes (the Cusack / Banks romance) felt discordant and others (Dano in the Pet Sounds studio) transcendent, there was something seriously moving in the cacophony.

9. Whiplash Award: The Revenant, w/ ‘71 and Tangerine

The Whiplash Award is reserved for singular, focused films which overwhelm me by sheer intensity. This year there were three contenders, and it’s really where my rankings break down: each of these held the title at some point in the last 20 minutes of making this list. And they couldn’t be more different. Jack O’Connell singlehandedly stole this award last year, and he nearly did it again with the criminally underseen ‘71. A moody, pressure-cooker action flick set in Belfast at the height of the Irish Troubles, it combines the earnestness of Gangs of New York with the nihilism of In Bruges. And speaking of earnestness, who could have seen Tangerine coming? When critics started raving about a movie shot on an iPhone 5 that follows two transgendered prostitutes on the streets of LA, I was hugely skeptical. And for the first 20 minutes or so, I felt vindicated. But somewhere along the way, all that abrasive, jarring energy transformed into something hilarious, tender, and vibrant — like Spring Breakers with a heart and soul.

The Whiplash Award is reserved for singular, focused films which overwhelm me by sheer intensity. This year there were three contenders, and it’s really where my rankings break down: each of these held the title at some point in the last 20 minutes of making this list. And they couldn’t be more different. Jack O’Connell singlehandedly stole this award last year, and he nearly did it again with the criminally underseen ‘71. A moody, pressure-cooker action flick set in Belfast at the height of the Irish Troubles, it combines the earnestness of Gangs of New York with the nihilism of In Bruges. And speaking of earnestness, who could have seen Tangerine coming? When critics started raving about a movie shot on an iPhone 5 that follows two transgendered prostitutes on the streets of LA, I was hugely skeptical. And for the first 20 minutes or so, I felt vindicated. But somewhere along the way, all that abrasive, jarring energy transformed into something hilarious, tender, and vibrant — like Spring Breakers with a heart and soul.

But this time around I have to give it to The Revenant. I may have some issues with Iñárritu’s style. He sometimes feels unnecessarily heavy, falsely burdened by the belief that glorified suffering equals meaning. What I can’t deny, though, is his power to captivate. This one stands out as a grand cinematic statement, an awesomely ambitious slice of chaos that my snobby hipsterdom has no right to dismiss. It’s my Mad Max of the year, over-the-top and wildly engrossing.

10. “Talky Flick” Award: Clouds of Sils Maria, w/ The End of the Tour, Queen of Earth, and 45 Years

This award (formerly “Take the Premise and Run”) has always been tricky to define; the moment I think I have it pegged down (“high concept”, “low fi”, “character-driven”?) an outlier comes along and upheaves it. The best descriptor I can give is “play-like”. These are films which are dialogue-centric, involve a very small cast of characters, and take place in a narrow window of time following a relationship-straining event — think A Separation, or The Loneliest Planet. It’s a testament to an amazing year in film that The End of the Tour (full review) is only one of three honorable mentions. Anchored by perfect performances from Segel and Eisenberg, it’s a wonderfully stripped down little film that cements James Ponsoldt (Smashed, The Spectacular Now) as one of my favorite contemporary filmmakers — if I weren’t handicapping for my rampant David Foster Wallace fanboyism, it probably would have been much higher on the list. Queen of Earth (full review) is perhaps the polar opposite; a deeply uncomfortable, Bergman-esque psychological drama about the deterioration of a female friendship. Amid a sea of samey indies, its bare-bones, hyperrealistic style was a serious gut punch. 45 Years is also a gut punch, but there’s nothing hyper about its realism. It’s an acutely-observed, sparse relationship drama that haunted me long past the credits rolled. Charlotte Rampling earns her praise and then some.

This award (formerly “Take the Premise and Run”) has always been tricky to define; the moment I think I have it pegged down (“high concept”, “low fi”, “character-driven”?) an outlier comes along and upheaves it. The best descriptor I can give is “play-like”. These are films which are dialogue-centric, involve a very small cast of characters, and take place in a narrow window of time following a relationship-straining event — think A Separation, or The Loneliest Planet. It’s a testament to an amazing year in film that The End of the Tour (full review) is only one of three honorable mentions. Anchored by perfect performances from Segel and Eisenberg, it’s a wonderfully stripped down little film that cements James Ponsoldt (Smashed, The Spectacular Now) as one of my favorite contemporary filmmakers — if I weren’t handicapping for my rampant David Foster Wallace fanboyism, it probably would have been much higher on the list. Queen of Earth (full review) is perhaps the polar opposite; a deeply uncomfortable, Bergman-esque psychological drama about the deterioration of a female friendship. Amid a sea of samey indies, its bare-bones, hyperrealistic style was a serious gut punch. 45 Years is also a gut punch, but there’s nothing hyper about its realism. It’s an acutely-observed, sparse relationship drama that haunted me long past the credits rolled. Charlotte Rampling earns her praise and then some.

Speaking of phenomenal acting, Clouds of Sils Maria has it in spades. Juliette Binoche is typically great, of course, but Kristen Stewart is a total revelation. Then again, I shouldn’t be surprised; if the film is about anything, it’s the murky line between “highbrow” and “lowbrow”, between “serious” actors and crowdpleasing stars. Like last year’s winner, it deftly combines the broad and laser-focused, with piercing dialogue giving way to gorgeous shots of nature set to a bombastic soundtrack. It’s a layered, complex, compelling piece of work. But most importantly, the conversations were genuinely fun to be a part of — one moment the two share (in a bar after a terrible superhero movie) had the best chemistry I’ve seen on screen this year.

Misc Awards / Defied Ranking

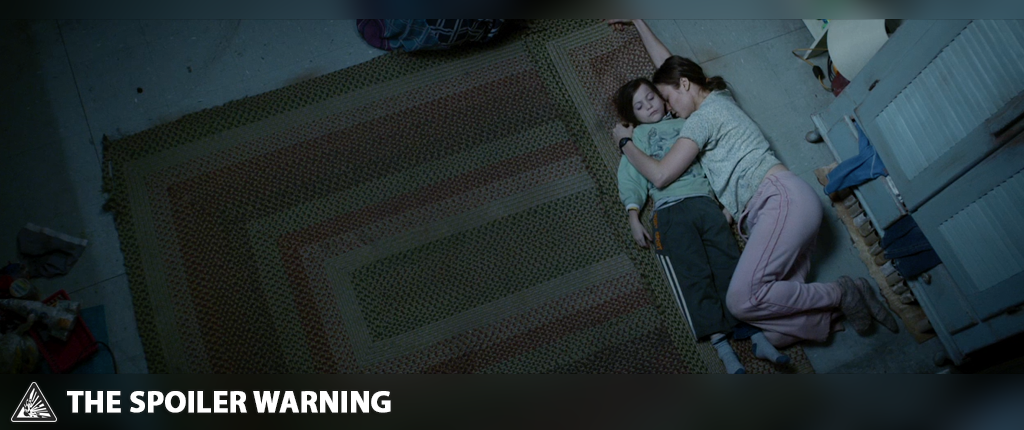

Vintage Stephen Award: Room, w/ Me and Earl and the Dying Girl

Despite not quite making the list, heartfelt indie flicks hold a special place in my heart. These “Sundance-y” winners tend to come in two flavors: stylish with hip detachment, or heartfelt but understated. Me and Earl and the Dying Girl achieved the rare accomplishment of being both. Like 50/50 meets Scott Pilgrim, it both says something sincere, and says it with the flare of a seasoned auteur. Even if it falters a bit in its obligatory tear-jerking conclusion, I’ve got nothing but love. Room (full review), on the other hand, flipped the genre on its head. A heartwrenching drama about a mother and son living in captivity, it doesn’t have a “hip” or “quirky” bone in its body. At the same time, it almost completely avoids the melodrama its dark subject matter ought to lend itself to. What’s left is less a tragedy than a tragic thought experiment; sadness is only context, background. The foreground is Ma (a brilliant Brie Larson) and Jack’s imagined universe, a sort of Allegory of the Cave set in the post- television era. That’s where it shines.

Despite not quite making the list, heartfelt indie flicks hold a special place in my heart. These “Sundance-y” winners tend to come in two flavors: stylish with hip detachment, or heartfelt but understated. Me and Earl and the Dying Girl achieved the rare accomplishment of being both. Like 50/50 meets Scott Pilgrim, it both says something sincere, and says it with the flare of a seasoned auteur. Even if it falters a bit in its obligatory tear-jerking conclusion, I’ve got nothing but love. Room (full review), on the other hand, flipped the genre on its head. A heartwrenching drama about a mother and son living in captivity, it doesn’t have a “hip” or “quirky” bone in its body. At the same time, it almost completely avoids the melodrama its dark subject matter ought to lend itself to. What’s left is less a tragedy than a tragic thought experiment; sadness is only context, background. The foreground is Ma (a brilliant Brie Larson) and Jack’s imagined universe, a sort of Allegory of the Cave set in the post- television era. That’s where it shines.

Tree of Life Award: Mad Max: Fury Road

I read enough film reviews to know that leaving Mad Max (full review) off a list is tantamount to heresy. So I thought it’d be fitting to, at least, give it the honorary Tree of Life Award, named for the movie I objectively respect more than I’m subjectively drawn to. Which isn’t to say I wasn’t drawn to this movie; I thought it was an overwhelming accomplishment. But that’s largely it. Like a great Metal band or the perfect Horror movie, I’ve learned that some incredible, enormously impressive things are simply not meant for me, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Respect from one Miller to another.

I read enough film reviews to know that leaving Mad Max (full review) off a list is tantamount to heresy. So I thought it’d be fitting to, at least, give it the honorary Tree of Life Award, named for the movie I objectively respect more than I’m subjectively drawn to. Which isn’t to say I wasn’t drawn to this movie; I thought it was an overwhelming accomplishment. But that’s largely it. Like a great Metal band or the perfect Horror movie, I’ve learned that some incredible, enormously impressive things are simply not meant for me, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Respect from one Miller to another.

It’s finally…

…over. Brain is dead. No more energy left for conclusions. Watch crazy movies about puppets. Sing Beach Boys songs. Cry on airplanes. Trust me.