I love documentaries for the same reason I hate reality television: everyone knows they’re being watched. It permeates everything. Every broad emotion, every word, every well-placed tear is unconvincingly choreographed to maximize our empathy for the subject. I love it, because people are such terrible actors. Not only do we still see them for who they are, we get to see who they think they ought to be in our eyes. Ego and superego battling on screen.

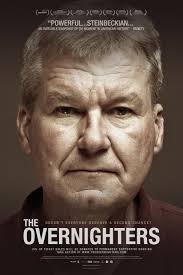

That dynamic informs The Overnighters in more ways than one. The film centers around Williston, North Dakota, where the recent oil boom has caused a massive employment spike rivaled only by a complementary spike in immigration. Poor blue-collar laborers from across the country have flocked to the promise of high-paying, low-barrier-to-entry jobs. When barriers to entry inevitably arise, they turn to Pastor Jay Reinke, whose “Overnighters” program allows them to sleep on his church grounds free of charge. Much to the chagrin of his holier-than-thou congregants. Not that they’d come out and say it explicitly — God, and the camera, are watching.

Of all the masks people hide behind, the Overnighters’ are the most empathetic: fresh haircuts, apologetic slips of profanity, lipservice to “the grace of God” when they really mean “thanks for the couch.” True hypocrisy is a luxury the poor can’t afford, and the Christian detractors are far more convincing in their imagined roles. Don’t get them wrong, it’s a wonderful ministry to help the poor! Praise Christ, serve the least of these, blessings and so forth. They’re just concerned, is all. Widows and lepers have a romantic King-James-ian sterility to them — but deadbeat baby-daddies and registered sex offenders? In their parking lot? Think of the children!

Reinke is hiding behind something too, and that complexity is what keeps this from being another weepy, finger-wagging morality tale. Wide-eyed and soft-spoken, his convictions are constantly at odds with his spine; through the funnel of “pastor” each glimmer of holy fire is reduced to a hunched, muted whimper. He knows exactly what sort of people his church is comprised of, but propriety won’t grant him the adjectives. Waging war without artillery, he’s left hunting for compromises: enforce stricter guidelines, omit details from the elders, keep the more “controversial” Overnighters in his own home or, sadly, send them packing. Whitewash every tomb. Strained relationships breed enemies on all sides, and he meets them all with the same cheery, loving disposition. A smile, a hand on the shoulder, a mostly-earnest laugh.

My Fundamentalist self would have seen his disposition as a Christlike joy in all circumstances. Today, I found it heartbreaking. It’s a portrait of a man who knows, deep down, that his worldview won’t survive this unbruised. That his love runs deeper than Christian platitudes, try as he may to conflate them. Doubt is the unspoken theme of the film: be it the American Dream or the Good News, everything is in flux. We first meet Pastor Jay as he’s ministering to his flock, greeting the sunrise with a cheery hymn. By the penultimate sunset, there are no hymns — and any reference to God sounds empty and perfunctory. When a meth addict misquotes “Psalms, no, Proverbs” to describe his sexual history as some frenetic demonic transaction, Pastor Jay feels no need to correct him. A stare, a pause, a vulnerable hug. “We’re both broken” he sobs, and it hurts to know how much he means it.

The Overnighters is a soulful ode to those who journey to any sort of Promised Land, only to find it doesn’t have room for them. It’s heart wrenching without being sentimental, damning without ever losing love for its subjects. It’s nothing but people, and it’s wonderful.

Get it on iTunes here