Rambling Preamble

“Cannes is a festival of contradictions.”

I’ve tried to start this post a handful of times throughout the festival, and it’s always been with some variant of that sentence. Sometimes it was written from a place of bemused detachment, marveling at the juxtaposition of high and low, glitz and grime: the shimmering starlet and monkey-suited undergrad strutting side-by-side up the same red carpet for Malick and Mektoub, Rambo and Rocketman. If there’s any difference at all between the 4-hour arthouse and the 90-minute popcorn flick, neither the swarming paparazzi nor the slinky DJ set (a mashup of French baby-making ballads and Entourage-douchebag chic a la Hit The Road Jack) are tipping their hand.

Sometimes it was written from an uglier vantage point: the sleep-deprived 6:30am line for a film I barely wanted to see; the cramp-footed death march home after hours of begging, armed with a sign and a sunburn and the sweatiest Men’s Wearhouse tux this side of prom. There, the contradictions took on a more bitter hue. Cannes as the ultimate empty facade; a monument to nothing but its status as monument; a Mediterranean grove of Instagram fig leafs obscuring 2am Big Macs and 5am alarms, restless hours wasted in a sun-stewed daze, and a level of bureaucratic confusion that makes the DMV look like a concierge at the Ritz. How many nights of sleep had I lost due to some ambiguous disclaimer or seemingly-vindictive constraint? How much money, in opportunity cost and airfare and exorbitant AirBnB fees, was I throwing down the drain to watch movies in a setting infinitely less comfortable than the theatre 20 steps from my apartment? Here we are, the quote real cinephiles endquote, literally begging for scraps (and frequently failing) while a horde of zombified financiers twirl and giggle up the iconic stairs for a film they’ll never know the name of which they’ll leave halfway through — after a hearty conversation, a snap of the screen with the flash fucking on, and a round of leisurely e-mails on a phone whose brightness is somehow higher than max. Look at them all, dead-eyed and hollow, parading their excess for nothing and no one. Does that Czech supermodel with the $10,000 bag really harbor a passion for British socioeconomic drama? That rat-pack crew of bachelor party wannabes, they’re all big Jessica Hausner fans now?

And sometimes, of course, a wonderful thing would happen, leaving all that cynicism in the rearview mirror. In those moments, the contradiction was actually the festival’s secret source of joy; the velocity of a low becoming a high, the dark that makes sudden light all the more blinding. At 7:25 you’re empty-handed, begging on the corner; 7:26 you’re merci beaucoup-ing some generous stranger; 7:27 you’re sprinting up the red carpet, side-stepping Iñárritu on your way through security; 7:29 you’re standing in the packed Corbeille to cheer on Almodóvar, Banderas, and Penelope Cruz; 7:30 the lights dim and something calm, and assured, and beautiful begins. It doesn’t matter where you were, what you had to do to get there, how you felt like giving up 5 minutes prior. You’ve experienced what cinema does at its best: it fills you, transports you, creates emotion from scratch. And at Cannes, even on the most meager of badges, that emotional high is never far from reach. It’s a helluva drug, and it’s worth all the anguish…er, arguably.

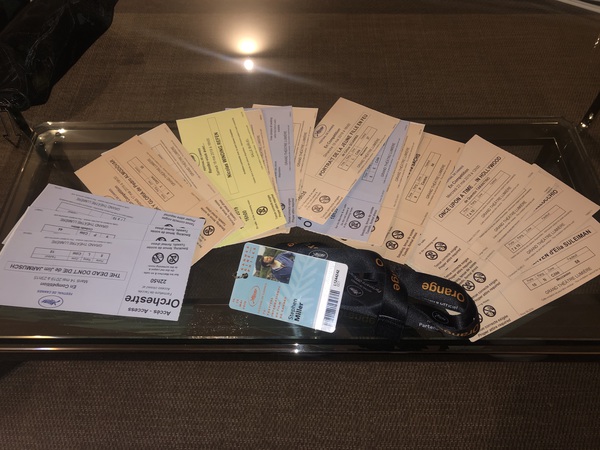

So here I am, on my flight out of Nice, wondering how I can possibly summarize these two frantic weeks in a legible form factor. I guess I can start with stats. Over the course of 12 (or 10, depending on how you count) days, I saw 27 things this year. That included all 21 films In Competition within 24 hours of their debut, 20 of which were at the Lumière, 14 of which were black tie premieres (“galas”). It also included 2 Out Of Competition premieres at the Lumière, 2 Un Certain Regard premieres at Debussy, 1 ACID premiere at Studio 13, 1 director rendezvous at Buñuel, and unfortunately 0 Lighthouses. 15 of these came from begging, 8 from last minute lines, 3 from the cinephile office and 1 from the town hall.1 On my “worst” three days I only saw a single film: once due to failed or poorly-communicated lines, twice due to Tarantino-mania. On my “best” day I caught 5 things: Mickey and the Bear (ACID) in the morning, a Nicolas Winding Refn talk in the afternoon, then back-to-back galas of Claude Lelouch’s The Best Years Of A Life (Out Of Competition), Corneliu Porumboiu’s The Whistlers (In Competition), and Gaspar Noe’s Lux Æterna (Out Of Competition, and batshit great.) At 55 minutes, Gaspar’s midnight screening was by far the shortest. At 3 and a half hours which felt like 8, Kechiche’s Mektoub, My Love: Intermezzo was by far the longest and, also, the worst. On one night I managed to sleep 8 full hours. For two days I managed to eat all 3 meals. Zero caffeine was ingested on this trip, which is a challenge I’m still not sure I needed to take.

Okay, now on to the good stuff: how should I talk about the films themselves? I’ve toyed with a few options. I could list everything I saw and rank them in some way. Or I could cherry-pick individual films which moved me and do long-form writeups. Or I could follow the precedent I set last year, and do day-by-day recaps which in turn break out into longer reviews. With time, I’m sure I’ll get a little bit of everything. But for now, I’ll settle on this: a chronological list of everything I attended, paired with extremely brief thoughts, and ending with a stack rank of all 21 In Competition films. All of this is off the cuff and likely to change; stay tuned for meatier reviews later.

The Films (and events) of Cannes

In total, there are 12 days of the festival. The first features only a single Opening Film; the middle 10 are standard festival fare (multiple premieres and rescreenings of the day prior); the last is devoted entirely to reprises and one out-of-competition Closing Film. To denote the track, I’ll use [CO] for Official Competition, [UCR] for Un Certain Regard, [OOC] for Out Of Competition, [ACID], and [MISC]. I’ll also use [P] and [R] to denote Premieres and Reprises respectively. Every CO and OOC film was seen at the Grand Lumière, except for Sibyl which was reprised in the Buñuel theatre. UCR was always Debussy, ACID was Studio 13, MISC was Buñuel.

DAY 1

- Jim Jarmusch’s The Dead Don’t Die [CO][R] was a bit of a deflated opening for the festival: while having plenty of his signature elements (wry sense of humor, detached characters, methodical pace, one earworm of a song), it never really picked up steam. At its best, it was very absurd and very silly; at its meta-narrative worst, it was a total dud. Still, I picked up my first red carpet of the festival!

DAY 2

Annie Silverstein’s Bull [UCR][P] is right up my alley: a tender, understated coming of age story about a young Southern girl (Amber Havard, who reminds me of a younger Brie Larsen in the best way possible) learning to control both her own anger and the rage that surrounds her. It didn’t exactly pack a wallop, but it landed exactly where it needed to in my heart. Also, it started what would begin one of the trends of the festival: films dealing, either explicitly or implicitly, with opioid addiction.

Ladj Ly’s Les Miserables [CO][P] packed precisely the wallop Bull lacked. It’s a riveting thriller about police brutality, systems of power, and a society on the brink of uprising. Comparisons with Do The Right Thing abound, in theme if not in style (for better or worse, Ly opts for a much more traditional narrative approach). It may have benefited a bit from its placement in the festival (Jarmusch happened to be an easy act to follow), but it remains an extremely impressive debut. I would not be at all surprised to see this in the Foreign Language Oscar race.

Kleber Mendonça Filho & Juliano Dornelles’ Bacurau [CO][P] is a movie I respected much more than I loved. It’s a parable about imperialism in the key of Jodorowsky; a slow-burn psychedelic Western that improbably pairs B-movie thrills with a resonant social message. Unfortunately, my tolerance for “weird” was a bit too low following my post-Miserables high, and while certain images will stay with me (particularly a scene involving a naked couple and shotguns), I never quite clicked with the tone.

DAY 3

Mati Diop’s Atlantics [CO][P] may just be the sleeper hit of the festival: a hypnotic fable about loss and grief set in Dakar, Senegal. Diop is the first black woman to have a film premiere In Competition—let alone to receive an award!—and her aesthetic sensibilities are everything here: gorgeous lights and shadows, the deep blues of a lapping ocean tide, the slow hint of smoke in the night. This is a quiet, lovely, meditative debut, and it’s one of those films that only gets better with time.

From here on out my day was defined by mistakes. While begging for a ticket to the new Ken Loach film, I received an invitation to the bizarrely-sought-after Rocketman [OOC][P] by mistake…and promptly gave it away. Why? So I could be 3 hours early to the Loach line, of course! That line was never let in, and I walked home dismayed and Elton-free.

DAY 4

Ken Loach’s Sorry We Missed You [CO][R] was well worth the wait and early wake-up call. An intimate drama about a delivery van driver and his caretaker wife, the film picks up right where I, Daniel Blake left off. Yes, unemployment is a vicious cycle, but sometimes employment can be no less cruel. Both films feature a near-identical conversation, a protagonist bemoaning “I’m trying my best” only to be told that it “isn’t enough.” On paper, the sentiment would feel about as subtle as a sledgehammer. Under Loach’s careful, empathetic gaze, it’s a potent call to action: We are owed life and dignity at a bar that “best” can easily clear. In the wake of Uber and Lyft’s recent IPOs, that call is more urgent than ever.

Jessica Hausner’s Little Joe [CO][P] is an odd little film which hovers somewhere between the lush romanticism of Amelie and the glossy remove of Killing of a Sacred Deer. A Sci-Fi drama about mind-controlling flowers (and, by inference, antidepressants), it’s conceptually interesting — and, at times, visually inventive. But after exhausting all its stylistic and substantive ideas within its first 15 minutes, it just sort of coasts…and coasts…and coasts…Some loved it; I found it one of the weakest of the fest.

Pedro Almodóvar’s Pain and Glory [CO][P], by contrast, knows exactly what to do with a lush color palette. That should surprise no one familiar with his work. What might be a surprise, though, is just how autobiographical the film is. It’s hard not to read it as the culmination of an entire career, a hindsight-soaked ode to success and hardship, loneliness, yearning, creativity and its many sources. Above all it’s about the sacrifices made on the journey of life; both the people we sacrifice (friends, lovers) en route to our dreams, and the people whose sacrifices we indebt ourselves to (a knowing schoolteacher, a longsuffering partner, a mother’s indefatigable spirit). Come for Antonio Banderas’ career-best performance as a thinly-veiled Almodóvar; stay for the soul that infuses every frame. What a satisfying work of art.

After such a high, I’m mildly embarrassed to report that I gave away my late-night invitation to see two episodes of Nicolas Winding Refn’s Too Old To Die Young [OOC][P]. Sleep comes for us all.

DAY 5

Annabelle Attanasio’s Mickey and the Bear [ACID][P] is another charming, if not particularly novel, entry into the coming-of-age genre. The film, which first premiered at SXSW, follows a few weeks in the life of Mickey Peck, an 18-year-old on the cusp of graduation who spends her days caring for her hard-drinking, veteran father. It’s hard not to see parallels between this one and Leave No Trace; but where Granik’s vision of father-daughter strife is defined by empathy, Attanasio’s gets at something decidedly more prickly. Its familiar subject matter is elevated by two excellent leads — Camila Morrone as Mickey, and James Badge Dale as her father Hank.

I then ditched the Wild Goose Lake premiere to catch Nicholas Winding Refn’s Director Rendezvous. He didn’t disappoint. Refn is an engaging conversationalist who is exactly as pretentious as I’d expected, but quite a bit more self-aware about it than I’d given him credit.

Claude Lelouch’s The Best Years of a Life [OOC][P] was largely just a way to pass the time between screenings, and I admit that I am not its target demographic. A sort of octogenarian Before Midnight, it revisits the cast of Lelouch’s acclaimed A Man and a Woman (1966) to add a final coda to their love story: what it was, what it might have been, I think you get the picture. Wistful, saccharine, and gooey to the core, it was all pleasant enough, I suppose—but interspersing archival shots from the ’66 classic with this one felt like sprinkling caviar on a Krispy Kreme.

Corneliu Porumboiu’s The Whistlers [CO][P] has all the right ingredients: a bold stylistic vision, a dynamite quadruple-crossing plot, and a lovely setting (Tenerife, where I’m presently headed). Unfortunately, in his nonlinear slicing and dicing for the sake of “cool”, Porumboiu severs anything resembling an emotional core. That may well be the point, of course — some subversive message about the Romanian surveillance state and its ability to hollow you out in the name of predictability — but the heart didn’t feel what the brain observed. I needed more to sink my teeth into if I wanted to stay awake.

Gaspar Noe’s Lux Æterna [OOC][P] was exactly the wake-up call I needed. A sort of epileptic, acid-laced Birdman, his midnight mockumentary about a film shoot gone wrong (starring Béatrice Dalle and Charlotte Gainsbourg as themselves) starts uncharacteristically slow and builds to a glorious, screeching crescendo. On the one hand, it’s a silly, self-referential exercise. On the other? I completely adored it.

DAY 6

Diao Yinan’s The Wild Goose Lake [CO][R] premiered on the same day as Porumboiu’s film, and the comparison somehow detracts from both. Here is another aesthetically gorgeous thriller which piles its twists on so thick, it’s hard to feel anything for anyone. At a certain point, the two plots even started to bleed together in my mind (my own fault, of course, but it is what it is). I dug the action choreography, and the night shots of a noir-y, rain-soaked China were really something. But if there was a beating heart to any character, it was sadly lost on me.

Celine Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire [CO][P], by contrast, might have more of a beating heart than the other 20 films put together. It’s a period piece about two women in very different life situations — one an unwilling bride-to-be, the other a portrait artist hired to paint her in secret. I won’t reveal much about where it goes (like all films at Cannes that weren’t made by Tarantino, I went in knowing nothing but the title and director). Instead, I’ll just say that it floored me, combining the passion of Call Me By Your Name or Carol with the social malcontent of a vintage bodice ripper. A gorgeous film that doesn’t waste a second. Easily one of the festival’s best.

Terrence Malick’s A Hidden Life [CO][P] has been heralded as a return to form. Some will say Malick is back, others will say he never left. Having skipped everything of his since The Tree Of Life, I’m not fit to weigh in either way. What I can say is that it feels like a combination of old and new Malick, and for the most part that’s a good thing. A 3-hour historical drama set in WWII Austria, it mashes up all of his modern fixations (spinning camerawork, whispered narration) with his classic aesthetic (Tarkovskian landscapes, hyper-religious sentiment, the essence of what makes us good) — a Big Film about Big Themes, it makes all of his maximalist impulses feel earned. And being present at its premiere, just a few rows from the director, was an honor I won’t soon forget. So why did I only like, never love, this one? Maybe it’s the subject matter. I couldn’t shake the feeling that everything had been done before, and done better — either by others (compare the claustrophobic prison scenes to Son of Saul) or by Malick himself (the intimate family moments of The Tree Of Life, the soul-searching desperation of The Thin Red Line). All of its beauty felt slightly misplaced, somehow. Still, I can’t wait to see what he’ll set his sights on next.

DAY 7

Maryam Touzani’s Adam [UCR][P] is, thematically, exactly the sort of thing I tend to adore. It’s a delicate portrait of pregnancy, motherhood, and female bonding set in a Casablancan bakery. And it occasionally lived up to that premise. There are moments of wordless, naturalistic beauty here unlike any other film I caught at the fest. Those are exactly the reason I go to UCR screenings. But the connective tissue between those moments felt too thin, somehow, less interested in telling a story than simply moving us from one perfunctory beat to another. In the end, as much as I loved the performances, I felt the film itself was only half baked.

Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne’s Young Ahmed [CO][P] did much more for me on the “naturalistic drama” front. If you’re familiar with the Dardenne catalogue, you probably know the basics: a pressure-cooker character piece which takes an extremely simple premise and milks it for every ounce of pathos it can muster. What sets this one apart, though, is the social element. Centered around a Belgian teenager on the cusp of religious radicalization, there are about a thousand ways the story could have fallen apart: too extreme and it’d veer into propaganda, too gentle and it’d be toothless and trite. Thankfully, they thread the needle beautifully, granting Ahmed terrifying flaws without ever losing sight of his empathetic core. I laughed; I cried; I stayed on the edge of my seat. I fell in love with this quiet little film.

Ira Sachs’ Frankie [CO][P] is also quiet and appropriately small, but I can’t say I felt the same enthusiasm for it. Maybe it’s a problem of location. In Love Is Strange and Little Men, Sachs’ characters are imbued with a lifetime of familiarity: we know exactly which streets they’d walk, which apartment they’d nest in. This time they’ve relocated from New York to Portugal, and something seems to have shifted in transit — the nuance is still there, as is the pitch-perfect dialogue that defines all of his work. But absent is the feeling that I truly know them as people, rather than a collection of clever signifiers. I enjoyed this one enough for what it is, but I can’t say it left much of a mental footprint.

DAY 8

The majority of this day was eaten by Tarantino mania: 5 hours of begging on the same street corner, no luck. Do I wish I’d done something else with my afternoon? Do I resent the woman who showed up 30 minutes before the screening and snagged a ticket right next to me? Sure, sure. But you live and you learn.

Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite [CO][P] took whatever lingering frustration I might have had and squashed it like a…well, you get the idea. How can I describe this genre-defying masterpiece? It takes everything in the director’s ouvre — action, horror, the darkest of comedy — and blends them together into something both profoundly moving and relentlessly entertaining. I loved everything about this movie: its brilliant construction, pitch-perfect characterizations, meticulous framing, uncompromising message about economic strife. In a way, Bong Joon Ho out-Loaches Loach: If you’re looking for a parable about the cyclic nature of lower-class living, this is it. Standing in applause as the credits rolled, I was certain this would be my favorite of the festival. I was right.

DAY 9

Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood [CO][R] was, of course, the biggest draw of the festival. 25 years after the Palme-winning Pulp Fiction, the director was back with a kickass cast and the sort of premise festivals swoon over: movies about moviemaking, about the glamor and insanity of Hollywoods gone by. And, in classic Cannes fashion, all my effort meant zilch. After a full day of begging and a groggy morning spent waiting in a meaningless line, I finally scored my ticket by accident: a stranger calling to me from the red carpet and handing me a spare ticket moments before the film began. So, was it worth all the hype? I’m giving it a firm “yes”. In some respects, Tarantino’s latest marks a huge departure, trading giddy violence and exploitation for a glossy trip down memory lane that wouldn’t feel out of place next to Hail, Caesar!. In other respects, it is very much a Tarantino film, for some reasons I can mention (its sense of humor, signature panache) and others I won’t. This is the movie DiCaprio should have won his first Oscar for, and Pitt is better than he’s been in years. It may not be the consensus pick Cannes was expecting, but I loved it all the same. And I think I mostly agree with that contentious letter. More than anything else in the festival, this one really benefits from going in blind.

And, having successfully caught the most sought-after film of the festival, I took the night off with my girlfriend to have a bite and a drink, watch Jackie Brown on an iPad, and promptly fall asleep.

DAY 10

Xavier Dolan’s Matthias & Maxime [CO][R] was the perfect fit for an early-morning screening: an unassuming talky flick with layers of emotion hiding up its sleeve. I was surprisingly moved by this film, and by Dolan’s performance in particular, which perfectly captures the way trauma can cause love and aggression to intermingle. His directorial vision was no less assured: a few touches (certain music cues, one beautiful scene shot through frosted glass) got me real good. As with many of the festival, I think the less you know about this one the better it will land, so I’ll leave it at that!

Arnaud Desplechin’s Oh Mercy! [CO][R] also had a unique directorial vision, but I can’t say it moved me in the same way. A lugubrious procedural about the elusive nature of truth, it’s well crafted on paper — and acted the hell out of by Léa Seydoux and Sara Forestier — but fundamentally lacking, to me. Maybe this is yet another example of my own language barrier bringing a film down, rendering dialogue that ought to pop into inert Philosophy 101 text. Either way, for all its style, this was my least favorite film of the festival…for a few hours, that is.

Abdellatif Kechiche’s Mektoub, My Love: Intermezzo [CO][P] would handily take the throne just a few hours later. I can’t decide which is more sad: that I stayed up until 2am to watch this 212-minute dry-hump of a film premiere, or that some thousand poor souls woke up at 7am to do the same thing sober. Articles have emphasized the film’s contemptible male gaze, and in particular the 20-minute cunnilingus scene (which somehow manages to be both unsimulated and the least realistic sex I’ve ever seen on screen). Hell, I’ve even been quoted in some. But the truth is, the walk-outs started long before the B-grade pornography began. Some left after about an hour, during the nightclub scene that felt like it would never end. Others left an hour and a half later, when the nightclub scene had still failed to end, despite having added virtually zero dialogue or character growth of any kind (unless twerking and downing enough shots to take down an elephant counts as “growth”). At a certain point in the evening, when at least half the audience had already left and we were sure the credits were about to roll, my friend checked his watch. It was only midnight. There were at least 100 minutes left to go. The laughter that followed, and continued throughout the rest of this trollish endeavor, was the evening’s only redeeming quality. People trying to compare it to The Brown Bunny or Southland Tales are seriously missing the mark. Those were contentious films which took it too far; this one is barely a film. Sit through this entire thing in a dark theatre, phone out of sight, and find one thing to praise about it. I dare you.

DAY 11

Marco Bellocchio’s The Traitor [CO][R] came as a welcome change of pace after the inane evening that preceded it. A sprawling procedural about the trial of ex-mafioso Tommaso Buscetta, the film rises or falls on its lead’s performance. Thankfully, Pierfrancesco Favino delivers the goods: alternatingly thunderous and timid, blustering and heartfelt as the situation demands. The film around him is slowgoing, methodic, and not quite as gripping as it ought to be — when it veers into Season 6 Sopranos territory it feels oddly inert. But those inert moments are few and far between; for the most part, this riveting courtroom drama is well worth a watch.

Elia Suleiman’s It Must Be Heaven [CO][P] is a small wonder of a film, managing to be both wistful and hilarious while barely saying a word. Armed with the most meticulous mise-en-scène of the festival, Suleiman highlights the minute absurdities of daily life, both in his hometown of Nazareth and in the places he visits (Paris, New York City). He isn’t the first to tap into this well, of course; comparisons to silent film, or the work of Jacques Tati, are plentiful and deserved. But I’m struck less by his knack for comedy than by his knack for composition; or, rather, by how he makes composition into its own sort of comedy. Too humble to be my favorite but too well-crafted to be much less, I have a feeling this one will only grow with time.

DAY 12

- Justine Triet’s Sibyl [CO][R] was my last film of the festival, and the only one I didn’t manage to catch at the Lumière proper. To be honest, after 11 days of begging, I’d been too burnt out to try. But packed into the Buñuel after a relaxing day of wandering the town, I was probably in the best possible mood to enjoy this. A tragi-comedy about a therapist who uses her patient’s lives as fodder for her novel, it’s precisely the sort of meta-meta fare the festival eats up. And you know what? I ate it up too! Funny, thought-provoking, and anchored by an excellent performance from Virginie Efira, it was the perfect snack to wrap up the trip; not too heavy, not too light.

In Competition, ranked

Phew! So there you have it. Everything I saw at Cannes. Now, as promised, I’ll give a quick ranking of the Competition films, which will almost certainly change by the time I wake up tomorrow:

1: Parasite

2: Portrait of a Lady on Fire

3: Pain and glory

4: Les Miserables

5: Sorry We Missed You

6: Young Ahmed

7: Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

8: It Must Be Heaven

9: Matthias & Maxime

10: Atlantics

11: A Hidden Life

12: Sibyl

13: Frankie

14: The Traitor

15: Bacurau

16: The Whistlers

17: The Wild Goose Lake

18: Little Joe

19: The Dead Don’t Die

20: Oh Mercy

21: Mektoub, My Love: Intermezzo

Outro

Cannes is a festival of contradictions, and I am no exception. Sitting here in my hotel in Tenerife (where I landed some 2/3rds of the way through this post), I’m unable to sift out the good from the bad. Stacking up moments of deep frustration against rapturous delights, the stressors of an opaque bureaucracy (I still recite names and showtimes when I try to fall asleep at night, like some obsessive-compulsive human Moviefone) against the delicate, the subtle, the empathetic, the profound. Maybe there’s no point in untangling it; maybe the 8am Ken Loach needed that 3am Big Mac just as surely as Malick needed my sweat-chilled suit. Mucinex and masterpieces, dolor y gloria. There’s something to be said for fighting for the things that you love, for love being wrapped up in the fight itself. I’m empty, and exhausted, and energized, and full. I never want to go to Cannes again. I’ll see you there next year.

-

Take note, future owners of a Cinephile badge: if you are trying to catch In Competition premieres, begging is by far the most efficient way to get in the door. It’s also incredibly easy for afternoon-after Competition screenings (which is lucky, because it also happens to be the only route you’re allowed to take). Lines are great for morning-after Competition screenings and any Un Certain Regard. The cinephile office is good for backup screenings and panel discussions. The town hall is generally useless and bewilderingly opaque, except for those moments when it suddenly isn’t.↩