TLDR: Cannes is Coachella with fewer drink options, In My Room is an amusing parable about masculinity, Dogman a pressure-cooker character piece with more than enough bark to make up for its lack of bite, Sorry Angel is a charming little period piece which accomplishes exactly what it needed to and little else.

Intro

Astute readers may note that it has been almost a full week since my Cannes Day 0 post.

See, when I set out for this Three Days In Cannes thing, I wasn’t entirely clear on the details. Here’s roughly what I’d imagined: four nights on the French Riviera, attending what would effectively be a low-key, exclusive, single-track conference on cinephilia which just so happens to include celebrities. 2-3 films would screen a day, and in between there would be free-flowing wine, shameless mingling, and comfy chairs for online movie reviewing. It would be chaos, but a restrained chaos with plenty of room for solitude.

As it turns out, three days in Cannes is less like a conference and more like a Black Friday sale at a Hugo Boss with the thermostat on the fritz. With two weeks and press badges, I imagine it might be a fairly comfortable, even relaxing, experience. With zero invitations and an impetus to see as many films as possible on a very limited schedule, it’s madness. Chaos. It’s thousands of sweaty Europeans smoking in formal wear at 3pm on a Thursday, forming a single-file-until-the-moment-some-douchebag-who-let’s-be-honest-is-always-male-and-always-French-and-always-has-whimsical-shoes-which-are-not-by-any-convention-black-tie-realizes-that-single-file-is-a-bourgeois-convention-and-we’d-all-be-better-served-by-a-Mad-Max-style-free-for-all queue, sunburned, hoping to catch an arthouse flick whose name they don’t remember. These lines are often formed after security, which means no food or drink, much less cozy laptop lounging. It’s Coachella in France without the overpriced Bud Light option; it’s an outdoor dinner party with the wrong dress code and no open bar and a survival-of-the-fittest invitation scheme; it’s a dry wedding in California. In short, again, madness.

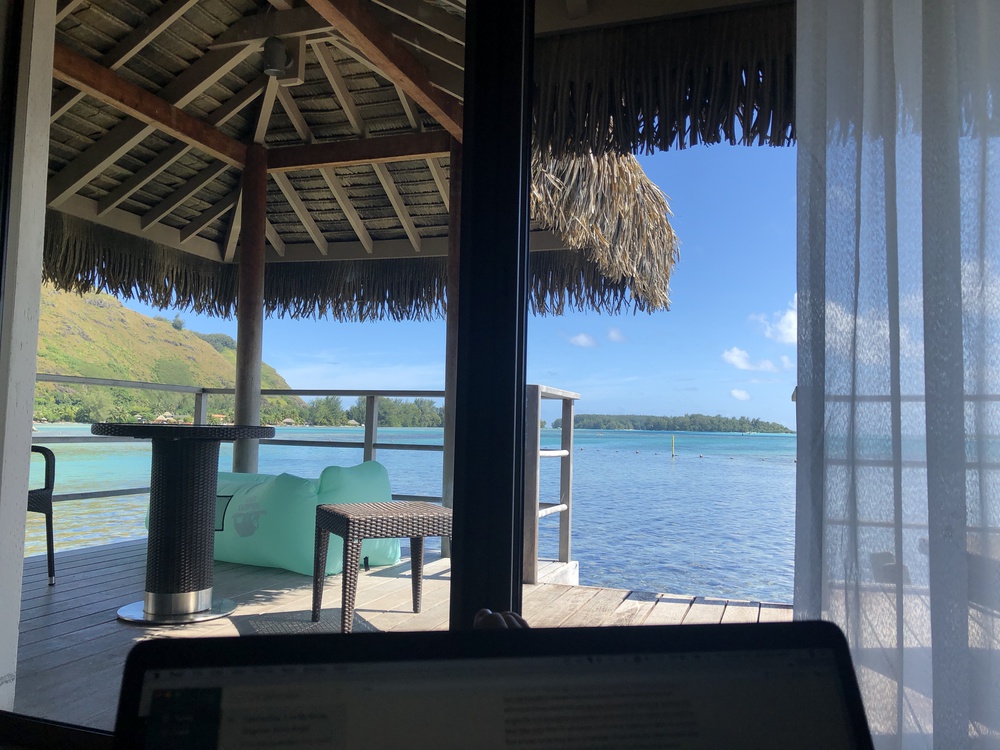

And I loved the madness. I wouldn’t trade it for the world. But madness is a situation far more conducive to 4-hour-nights sleep and lone 11pm breakfastlunchdinner combo meals than it is to a rigorous blogging schedule. So I quickly gave up on writing these in realtime, and opted instead to save them for my present situation: lounging in a bathrobe in an overwater bungalow on a French Polynesian island with my girlfriend, with nothing to do till dinner time and coffee and scotch in tow. I am now, geographically and metaphorically, about as far from a sweaty line in Cannes as is humanly possible.

So, OK, I think I’ll keep these in the daily-update format, paragraph or two per film, and for titles I really dug I might break into long form reviews later. So let’s get to it! Our Thursday Cannes journey opens, as always, in a big ass line.

In My Room (3.5/5)

This particular B.A.L begins at the Theatre Debussy around 10am. My ~36 hour travel marathon having been “totally cured” by a 4 hour nap and espresso chaser, I was ready to see my first (and only) premiere from the Un Certain Regard selection: Ulrich Köhler’s In My Room. A film about which I knew absolutely nothing. But the crowd was admirable, the caffeine was bumpin’, and once seated I was able to give a (reciprocated!!!!) head nod to Benicio Del Toro, two rows ahead of me in a green baseball cap. Thus, already complete, my day began.

Going in blind, it turns out, was the perfect way to see In My Room; I’ve read the public synopsis since, and am quite disappointed in how much it reveals. But since there is no way this film will come to the states without its premise being spoiled, I’ll give you some (not all) of the major details. Armin (Hans Löw) is a not-quite-middle-aged-but-not-quite-young man whose life has wound up, if not in a rut, at least in a series of aggravating snares. Like many in their late 30’s or early 40’s, he has found that occasionally tripping over modestly-set bars is more demoralizing than aiming for higher ones and failing. He is a videographer/photographer by trade, but he never seems to be given an interesting subject — and on the rare occasion he is (as shown in a very funny opening gag which, at first, might seem like a projector glitch) he ensures it won’t happen again. He maintains a relationship of sorts with his parents, but it feels fractured and strained even in those moments it ought to be profound: a breakfast conversation with his father, while his grandmother lies dying in the adjacent room, plays less like familial bonding and more like two old men struggling to make small talk on a golf course. Single, he still frequents epilepsy-beat dance clubs and is still able to pick up women, but he fumbles at the ten yard line for reasons that aren’t monstrous so much as tone-deaf and apathetic. It’d be easy to say that Armin is selfish, but I think the more salient truth is that he’s too tired to advocate for anything, self or otherwise. Everything has gone soft, eroded: his gut, spirit, hopes, mood. Is there a pill to get that up?

Then, something happens. The recovering childhood Tim LaHaye reader in me wants to call it The Rapture (and a scene involving choir practice might back it up, slightly), but the truth is, we’re given about as much to go on as Armin is. He wakes up one morning to find that everyone living is gone. Cars have skid off the road, convenience stores are left permanently closed, planes (we imagine, given budgetary restraints) have fallen from the sky. His grandmother’s body is still where he left it, but the grieving man at the breakfast nook has vanished, and with him all vestiges of social obligation. Watching it dawn on him feels a lot like watching the first episode of Last Man On Earth, as quiet horror gives way to high speed joyrides, anarchy and fire. A more moralistic film might argue that this strange, new world is what Armin had really wished for all along: a place that doesn’t need him, bereft of any alarm to snooze or boss to satisfy or partner to complement or bereaver to console. In Köhler film, there’s nothing quite so tidy. Like yesterday’s date or a job assignment gone wrong, this disappearance seems like just another shitty thing that happened to Armin. A case of the Mondays gone apocalyptic.

There’s a common joke (whose source escapes me), about a man who finds himself stuck in an elevator and immediately reverts to Survival Mode, defecating in the corner and drawing straws to eat his fellow captives before a horrified technician discovers him some 25 minutes later. Armin’s transformation has the cadence of that joke. Despite the whole of modern civilization in his grasp, within minutes he is living in an agrarian wasteland: gnarled-bearded, nude, rifle in tow, wrangling sheep abreast his trusty steed. We get the sense that he wants this more than he has wanted anything pre-rapture; here is a place, finally, where he can feel of some use. Of some hard, simple, undeniable use. As an exploration of the male ego, it lands — like much of Köhler’s film — somewhere between tongue-in-cheek and sincere. But the longer it unfolds, that playful back-and-forth becomes deeper, more complex, and I won’t spoil it (though I’m sure stills at least partly will). There are echoes of Z For Zachariah here, as well as the aforementioned FOX show. Now that Armin can truly be anyone, who will he be? Will he build a simple life for himself, reimagined as all aspects of “Man” the 21st century has evolved beyond — Provider, Warrior, Tamer, Builder Of Things? Can he find contentment in life, now that he determines the rules? Or will that same selfishness, that cycle of apathy, reassert itself?

It’s a small movie, more parable than narrative, and its style is as subdued as its performances. But I quite liked this one.

Dogman (4/5)

I lied, before, when I said Cannes was all waiting in line. A few days before arriving, I was allowed to request a few invitations on an online form, and received exactly one: the 3pm showing of Matteo Garrone’s Dogman. Having an invitation affords you many luxuries, chief among them: being able to actually eat lunch. Well-fed, I entered the theatre.

In Gomorrah, Garrone effectively does for Naples what David Simon does for Baltimore: he zooms out to show how organized crime operates within the region, whose lives it touches and whose pocketbooks propel it. It’s a gritty, bleak, and sprawling portrait. If Gomorrah was The Wire, Dogman is an episode of The Sopranos, likely centered around Artie Bucco: a study of a man who is, at most, crime-adjacent, but whose life nonetheless becomes undone.

Marcello (Marcello Fonte) is, if nothing else, a people-pleaser. Whether out of self-preservation or genuine love, his driving impulse is to make people happy. He lives under the shadow of crime, in much the same way that a high-profile businessman might live under the shadow of corruption, but within that framework he operates as a Mostly Good Guy. He grooms dogs for a living, and treats all breeds with equal affection — whether floofy little poodle or towering mastiff. He smiles, constantly; a toothy reflex so well-worn it almost doesn’t matter if it’s sincere. He means it, in the permanent sense; he chooses it. He wants to take his daughter on vacation to the Maldives. He wants to be at peace with his community, to sit at the sidewalk cafe sipping espresso and being one in whom others confide. He plays second fiddle in the occasional theft, and trades a little coke on the side, though both seem to be more calculated vices than earnest bad deeds. We get the sense that Marcello isn’t out to line his pockets, so much as to extend an olive branch to some of his seedier neighbors: the criminal equivalent of buying a round of shots when you mostly dislike liquor, or joining a bachelor party strip club when you’d rather stay home. He is spineless, yes, but he is not without compass: after an overheard robbery involves throwing a puppy in the freezer, he drives back separately to rescue her. He views himself in the same way a lifelong Republican might view his role in the Trump Cabinet: an adult in the room who can pick small battles and mitigate damage. If it just so happens to also make him filthy rich, well, it’s an honor to serve his country.

The problem is Simon (Edoardo Pesce). The vein-bursting bulldog to Marcello’s whimpering Chihuahua, the Trump to Marcello’s Preibus, the Season 5 Tony to Marcello’s Season 1 A.J., Simon is never not on the verge of explosion. He snorts coke in front of his 10-year-old daughter. He bashes in heads for sport. He refuses to pay back his debts, no matter whom it pisses off. He cannot be reasoned with, not even by the eminently reasonable Marcello; his response to all rational suggestion is to nod, grunt, and do the damn thing anyway. He’s a bully. And as he becomes more and more unhinged, Marcello’s affable, yes-and disposition becomes his ruin. He loses his reputation as a trustworthy buyer. He loses his standing in the community, his seat at the espresso table. And after a botched robbery leaves him the sole, prosecutable suspect, he loses a year of life with his daughter.

Dogman is pretty cleanly split into two parts: God tests Job, Job beats God with a metal pipe. Fonte is a revelation in both the decline and the upswing, and a worthy winner of that Best Actor prize. He communicates all of Marcello’s contradictions with perfect control, never losing that plastered-on smile even when he’s screaming bloody murder. The film, like Simon, wears its short fuse on its sleeve: we know, without question, that everything will blow to bits before the credits roll. The joy is watching it get there. And while Garrone isn’t doing particularly much with this story — the obvious parallels between dog and man, or between man and governments; Marcello’s loyalty as a cautionary tale — there’s a grunginess to the proceedings that permeates everything. I loved the inevitability, the ticking-time-bomb of this film; loved basking in the dusty, sepia wreckage that is Marcello’s life. Some might find it too simple in its brutality, too unsubtle in its metaphors. I say not every breed can be subtle; not all are conducive to delicate trims, well-coiffed manes. Some are hulking, singular beasts. I had a blast watching Garrone tear off the leash.

Sorry Angel (3.5/5)

In what would become a recurring pattern on this trip, I didn’t actually set out to see Sorry Angel. Having somewhat enjoyed her prior film, Where Do We Go Now?, I spent the first two hours of this late afternoon / evening trying to catch the premiere of Nadine Labaki’s Capernaum. Which is to say, waiting in another Big Ass Line. Roughly ten heads away from the red carpet, I was turned away with that withering French smile I’d come to know so well. So I retreated to the Cinema Les Arcades for one of the few showings in my official Three Days track which would actually be subtitled in English: Christophe Honoré‘s Sorry Angel. Or, to use the more compelling French name, Plaire, aimer, et courir vite. Please, love, and run quickly.

I pride myself on having a fairly good memory when it comes to movies. I never take notes; when it’s good, the image burns. So maybe it’s damning with faint praise to admit that, one week later, Sorry Angel has left me with virtually nothing to criticize. It isn’t that I forget what happened, only that I’ve forgotten how any of it felt.

What happened: it’s either the late 80’s or the early 90’s, and the AIDS crisis is in full swing. Arthur (Vincent Lacoste) is a young, queer man living in Brittany. Charming. Playful. Handsome and knows it. A Free Love lifestyle set to a New Wave dance beat, he floats from partner to partner in a joyous daze. Jacques (Pierre Deladonchamps) is a middle-aged playwright just off the train from Paris, briefly in town for a speaking gig. He has an easy smile, a son whom he adores, and an experation date only a few close friends are aware of. When Arthur meets Jacques in an afternoon movie screening, he doesn’t know that he’s dying of that godawful disease. All he knows is that he suddenly wants to stay.

There’s a moment in Andrew Sean Greer’s novel Less (which I happened to be reading on this trip), where the protagonist — a writer about to “celebrate” his 50th birthday — reflects that he sometimes feels like “the first homosexual ever to grow old.” Young adulthood, there had been a template for that: there were generation after generation of youth culture and music to fall back to. Even 30’s and 40’s, there were always veterans out blazing the trail — including the poet, two decades his senior, whom he spent his San Francisco 20’s swept up in. But 50’s? AIDS had all but ensured no one made it that far. Here was uncharted territory.

Sorry Angel features a similar exchange. Jacques says that he often feels jealous of Arthur’s generation; they are more beautiful, more at ease with themselves. They know exactly who they are, in a manner that his cohort was never granted. I see, in Jacques, that same old guard Less remembered so fondly — the trail-blazing generation that, sadly, would never make it to middle age. And I see in Arthur the new souls who would: would finally be allowed to grow up, marry, travel the world, become protagonists in prize-winning novels that don’t end in tragedy; would have a period far enough removed from “the wild years” to use that phrase without irony. Arthur will eventually experience the ultimate luxury: he will become boring.

Through a series of vignettes, parallel and intersecting, we watch how their lives slowly change. Jacques opens his home to a former lover, too far gone in his own disease to take care of himself. He stands as a vision of the Jacques’ future, a symbol of the mortality he’s trying so desperately to stave off. Arthur continues to enjoy his freedom in the way only a young person can, taking on new lovers and (never irreparably) hurting old ones in his wake. He stands as a vision of Jacques’ past; of those years when life was sun-bleached and careless. As the disease worsens, and their love affair deepens, they finally treat the two head-on. We’re granted tiny hints of maturation in Arthur — glimmers of tenderness and understanding that will surely bloom into more offscreen. We also see life, again, in Jacques — vestiges of youthful exuberance, given to him freely while he still lives to receive.

It’s a lovely story, which keeps its scope small and never attempts to venture outside of it. Gone is the wild romanticism of Call Me By Your Name, or the shimmering eroticism of Carol. Sorry Angel isn’t much about longing at all. It’s about the conversations that happen in the cracks between grand gestures; a gentle portrait of two men and two generations. How the older teaches the younger; how the younger comforts the older. While that smallness is appropriate for the subject matter, and well worth the ride, it also doesn’t leave much fuel to burn. I enjoyed this one for what it was. Your mileage may vary.