March, 2015. The festival circuit has just ended, national premier is a few months away, and director Craig Zobel is slouched in a La-Z-Boy nursing a well-deserved beer. It’s been a wild, wild ride. He flips on Fox to catch that new Will Forte comedy everyone’s been raving about. Thirty minutes pass in silence.

“I’ve made a huge mistake.”

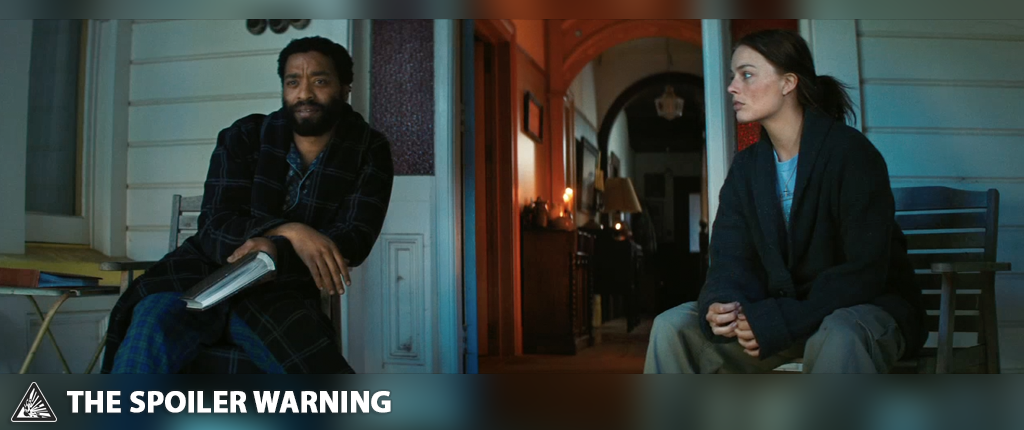

If I could describe Z for Zachariah with one word, it would be “odd.” Not in content, but in the fact that it exists at all. It’s an odd convergence of mismatched ideas, things which sound great individually but never really add up. Nuclear war has ravaged the earth, and Ann and Mr. Loomis believe themselves to be the only survivors. She clings to her faith, he clings to his science (why are those pronouns almost never reversed? Thank God / Science for Contact), but both know they have to rebuild. Forced together despite few commonalities, theirs is a tense union — and we have every reason to expect something will snap. Then hunky, Southern good ol’ boy Caleb wanders in from the Nicholas Sparks shoot next door.

Hold up. What was this movie supposed to be about?! You bring up themes of faith vs science, of romance vs cold patriarchal duty, of gnawing racial tensions; you present me with this murky relationship that promises to deepen into something terrifying or beautiful — and now after a half hour of lip-service, you jettison it all for a love triangle? And an imbalanced love triangle at that: we know virtually nothing about Caleb, except that the good Lord blessed him with rugged good looks, baby blues, and fortitude against radiation. It’s a truly bizarre twist, and one that the film created from scratch: even the book, targeted at ADHD-addled young adults, was content with two characters. That The Last Man On Earth mined so many laughs from such similar territory, only makes its lack of a payoff more pronounced.

Normally I’d be forgiving of missteps like this. It’s a small film, it took a risk, and it didn’t work. But like Interstellar, Zachariah unfolds with a sort of self-serious grandeur that practically begs me to nitpick. That ultra-brooding slowburn, those indulgent shots of nature, banal platitudes lobbed with the gravitas of Scripture — everything cries “Trust me, I’m an artist and I’m about to blow your mind.” After 80 minutes of failing to blow my mind, it busts out a shot-by-shot homage to Tarkovsky’s Stalker… and it’s probably the most affecting of the movie. Like Kubrick to Nolan, though, the nod feels less loving than delusional.

Excellent acting and solid ambience keep this from being a bust. But those can only take you so far. At some point, all that mood building needs to actually build something