There are two questions Sci-Fi can beg of me: what did it say, and how did it feel? Being well-versed in the fields Hollywood loves to bastardize, my bar for the specifics is unreasonably high. Whether they say it with dumb sincerity (Transcendence), playfulness (Lucy), or aggravating grandeur (Interstellar), most die by over-exposition. The best of them sidestep the specifics and go for the jugular. No one wants to know how Moon’s space station was architected, or whether Samantha actually runs Linux. There’s only one question worth asking: how would it feel?

Ex Machina takes this lesson to heart: first-time director Alex Garland has far more to say about the human psyche than science, and he tells you so up front. Set in an undisclosed location in a who-cares-how-soon future, the film functions less like a story than a three-character morality play. Nathan (Oscar Isaac) is a sort of Ghost of Sergey Brin Future; a wealthy, bearded brogrammer who lives in recluse, crafting the future with giddy disregard for privacy or ethics. His latest creation is Eva (Alicia Vikander), a humanoid robot who, he believes, will pass the elusive Turing Test. Caleb (Domnhall Gleeson) is flown in to conduct that test and, like any mid-level talent, he’s initially bogged down in low-level details. But true-to-type, Nathan insists on abstraction: it’s not about “stochastic processes” or hand-wavey explanations, but how it feels to meet her. So how does it feel?

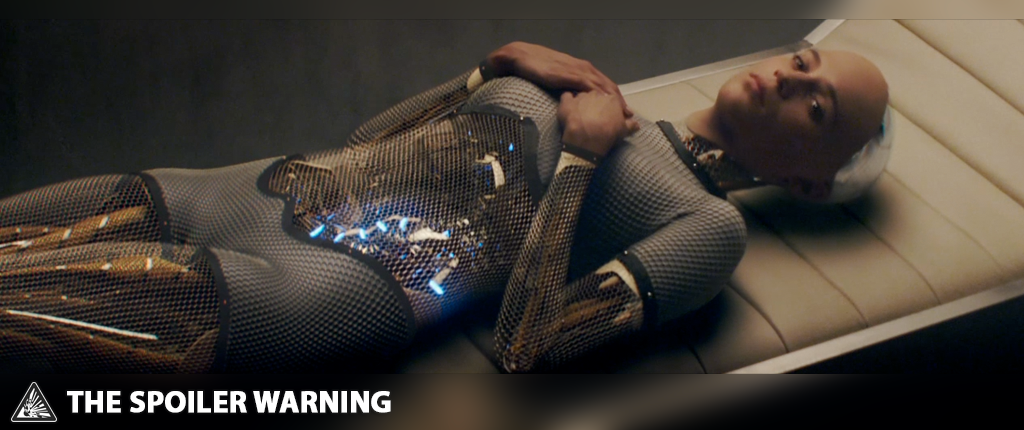

Exhilarating. And that’s why it’s the best film of the year, so far. Vikander’s Eva is the anti-Scarlett Johansson, lacking both the warmth of Her and the chill of Under The Skin. With literally unblinking focus, adolescent flirtation, eerie precision and just a hint of menace, she’s (brilliantly) never less than a machine. She’s set up camp in the Uncanny Valley, and the film dares you not to empathize. As the story unfolds with predictable shape, the texture is new and unsettling. You can feel it in every detail: gorgeous waterfalls flowing over industrial-gray concrete, nudity that defies the male-gazing camera, art and philosophy interspersed with orgiastic terror, a soundtrack whose fuzzy ambiance shouts louder than a Hans Zimmer choir. Something beautiful is happening, but it’s not yours to own. Nathan fancies himself Creator God and Caleb postures as a Savior, but the real Deus comes from elsewhere.

This one only gets better the more I think about it. Chris, Carson, and I review it at: