Cut to the chase: Want to see this year’s actual list? Head over to Decoding Everything.

Previous write-ups: Check out the last decade of end-of-year lists to get a sense of our similarities and differences.

Podcast: You can listen to my straightforward Top 10 list on The Spoiler Warning.

Introduction

I have a tradition of tallying my favorite films of the year and turning them into an essay for my blog. But for the last few years, I’ve been honored to contribute that essay instead to David Chen’s Decoding Everything newsletter. If you haven’t already, you should read it first: It’s a significantly more polished (and complete) encapsulation of my thoughts about the year in cinema.

Still, for the sake of continuity, I always like to post a little something extra for readers of my blog and/or this Substack. Last year, that came in the form of an Appendix. This year, I thought I’d shift gears and talk about tomorrow’s Academy Awards—and, in the process, give one last “hurrah” to the many films I loved.

For each category, I’ll share three opinions: which nominee will win, which should win, and what alternatives should have been nominated in their place. Because I think it’s only fair to judge categories I have some personal experience with, I’m going to omit a few:

- Animated Short Film, Documentary Short Film, and Live Action Short Film. I didn’t manage to catch any shorts this year, so for those of you making a prediction bracket of your own, I suggest you give it a Google!

- Documentary Feature. I only caught up with one of the nominees, No Other Land. It’s a phenomenal doc, and I’m personally rooting for it to win! But I can’t honestly judge it against a slate I haven’t seen.

- Music (Original Song). I’ve seen two of the four films nominated, and in the case of Emilia Pérez, I forgot the songs roughly 30 seconds after they stopped playing. On the one hand, it would only take me ~15 minutes on Spotify to rectify this problem and be a completist. On the other: This category is garbage and I don’t care who wins.

OK, now on to the awards!

Animated Feature Film

- Flow

- Inside Out 2

- Memoir of a Snail

- Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl

- The Wild Robot

What will win? If you’d asked me to predict this category a few months ago, a low budget Latvian film with zero dialogue, little exposition, and an intentionally stripped-down aesthetic wouldn’t have been high on my list of contenders. But awards voting bodies continue to surprise me this year, and by all indications, Flow is going to take home the prize.

What should win? In terms of quality, it’s a tie for me between Memoir of a Snail and Flow. Both are excellent. But for its sheer audacity (and what this win means for the category moving forward), I’ve got to give an edge to Flow.

What should have been nominated instead? This was a fairly weak year for animated features. Setting aside Robot Dreams (which was already nominated last year), the only three I loved (Flow, Memoir of a Snail, The Wild Robot) are already represented in this category. No notes!

International Feature Film

- Emilia Pérez

- Flow

- The Girl With The Needle

- I’m Still Here

- The Seed of the Sacred Fig

What will win? If not for the train wreck of negative publicity, Emilia probably would have had this in the bag. But I think even the stubborn, Bohemian Rhapsody and Green Book-adoring factions of the Academy know a lost cause when they’ve seen one. Whereas I’m Still Here continues to have a groundswell of support. It catapulted seemingly overnight from being a film many American critics hadn’t seen, to being a serious contender in multiple categories. It also happens to be excellent, and has no serious detractors to my knowledge. I think this is Walter Salles’ award to lose.

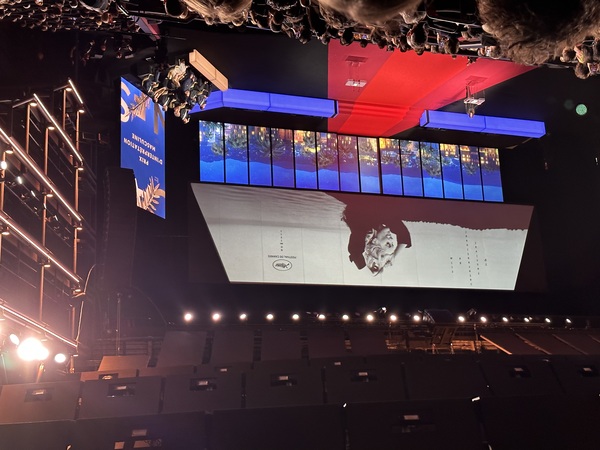

What should win? I think Flow, The Girl With The Needle, and I’m Still Here would all be worthy wins. But The Seed of the Sacred Fig is my personal favorite, both as a standalone work of art and as a potent political statement. Mohammad Rasoulof and his cast fled Iran in secret to attend the Cannes premiere, and cheering for them as they entered the Palais remains one of my most moving moments of 2024.

What should have been nominated instead? Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine As Light was one of my favorites of the year, and it’s a shame India didn’t submit it for consideration. Likewise for Poland and Green Border, a powerful work of docu-fiction which couldn’t be more timely given current anti-refugee sentiments and the recent change of tune regarding the Russo-Ukrainian war. Sub out Emilia Pérez (a movie I didn’t hate but certainly don’t think belongs in serious contention: You can listen to my scatterbrained thoughts out of Cannes) and The Girl With The Needle (a powerful, brooding arthouse drama which I liked just a tad less than the others).

Visual Effects

- Alien: Romulus

- Better Man

- Dune: Part Two

- Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes

- Wicked

What will win? I haven’t been following any of the buzz when it comes to these technical categories, so take all of these predictions with a grain of salt: I don’t know anything you don’t know. But I’d wager this is a dead tie between Dune: Part Two and Wicked. Going to give the edge to Dune: Part Two as a consolation prize for not winning much else.

What should win? I haven’t seen Better Man, but I have seen the other four, and think Dune: Part Two is the most deserving among them…with Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes just a smidge behind it. (The Robbie Williams biopic looks great, for what it’s worth, but it’s hard to imagine anyone out-CG-aping that franchise.)

What should have been nominated instead? It’s outrageous to me that the best action spectacle of the year, Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, isn’t getting a single awards nod. Drop Alien: Romulus and give something to George Miller’s epic.

Sound

- A Complete Unknown

- Dune: Part Two

- Emilia Pérez

- Wicked

- The Wild Robot

What will win? Same disclaimer as above regarding technical categories. I imagine Dune: Part Two has a solid shot here, and can also see a strong argument for A Complete Unknown given how vital diegetic music is to its success. But I think Wicked takes this as a last minute sub for Emilia Pérez.

What should win? The Wild Robot is an inspired nomination for this category. It’s less flashy in its use of sound than the other picks, but it’s the film whose sound design I find most personally memorable.

What should have been nominated instead? Again, Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga should be sweeping these technical awards. Drop Emilia Pérez to make room for it.

Costume Design

- A Complete Unknown

- Conclave

- Gladiator II

- Nosferatu

- Wicked

What will win? I wouldn’t be at all surprised if Wicked took the prize, and it would be a deserving victory. But I suspect the same voting bloc that swoons for Elizabethan period pieces and royal regalia will go all in on Vatican chic. I’m calling this for Conclave.

What should win? There are few categories I feel less opinionated about than Costume Design. But I found Nosferatu’s period aesthetic very striking, and a big part of that comes down to costuming.

What should have been nominated instead? I can’t say I know precisely where costumes end and makeup begins, but I Saw The TV Glow nails both in its eerie recreation of the 90s Nickelodeon look and feel. I’m as enchanted by Greenwich Village as anyone, but for the sake of variety, I’d let Mr. Melancholy and his minions bump out A Complete Unknown.

Makeup and Hairstyling

- A Different Man

- Emilia Pérez

- Nosferatu

- The Substance

- Wicked

What will win? It’s hard to imagine the Academy resisting the charms of Wicked. She’s green, for Pete’s sake! And it’s a metaphor for racism and other stuff, probably!

What should win? This is a stacked category, and there’s a decent argument for every nominee: Even Emilia Pérez, the punching bag of this year’s awards season, uses makeup and hairstyling in a way that is crucial to the story. But for me, it comes down to the two body horror flicks. While The Substance was the better film in my opinion, A Different Man is the one which lives or dies by its precise use of makeup. It nails it.

What should have been nominated instead? Even though I defend Emilia Pérez in this category, its inclusion is inextricably linked to its clumsy, ultra-binary handling of trans identity. Why settle for clumsy, when I can nominate a far better film about the trans experience which happens to have incredible hair and makeup? Give its spot to I Saw The TV Glow instead.

Production Design

- The Brutalist

- Conclave

- Dune: Part Two

- Nosferatu

- Wicked

What will win? None of these nominees would surprise me with a win, but I think Wicked is going to take it given the sheer scale of its production.

What should win? All five films impressed me with their production design (especially Nosferatu), but only one pulled it off on a shoestring budget. The Brutalist is the most deserving of the bunch, and doubly so when considering the constraints they managed it under.

What should have been nominated instead? I’m going to sound like a broken record, but I adored the look and feel of I Saw The TV Glow. It’s hard to cut anything in this category, but I’d lose Conclave as a matter of personal preference. It does an admirable job of recreating the Vatican; I’m just not as thrilled by it.

Music (Original Score)

- The Brutalist

- Conclave

- Emilia Pérez

- Wicked

- The Wild Robot

What will win? Normally I’d be inclined to bet on Wicked here, but I suspect the Emilia Pérez stragglers will split the musical vote. So instead I’m going with Volker Bertelmann’s excellent score for Conclave.

What should win? Bertelmann’s work on Conclave is great, as is Daniel Blumberg’s for The Brutalist. But by my memory, Kris Bowers’ score for The Wild Robot blows the competition out of the water.

What should have been nominated instead? The total lock out of Challengers from this year’s awards ceremony is bizarre, and nowhere is it more glaring than in the Original Score category. Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross not only should have been nominated; they should have won. Other highlights were All We Imagine As Light (particular Topshe’s song which closes the film, though I’m unsure where “score” ends and “soundtrack” begins when it comes to original compositions) and Alex Somers & Scott Alario’s ephemeral Nickel Boys score. Lose Wicked, Emilia Pérez, and (gun to my head) Conclave to make room for these.

Film Editing

- Anora

- The Brutalist

- Conclave

- Emilia Pérez

- Wicked

What will win? Judging by its awards season momentum, I think this is Anora’s to lose.

What should win? I’ve gotta go with the consensus here: Sean Baker’s linear editing process is vital to the momentum of his films, and he knocked it out of the park with Anora.

What should have been nominated instead? Count this among the multiple categories which Nickel Boys ought to have won by a landslide: Nicholas Monsour’s elliptical, rhythmic editing is crucial to the film’s artistic success. Also throw in Challengers for those heart-pumping tennis sequences. No hard feelings, Emilia Pérez and Wicked.

Cinematography

- The Brutalist

- Dune: Part Two

- Emilia Pérez

- Maria

- Nosferatu

What will win? Voters will be captivated by the way Greig Fraser managed to turn Dune: Part Two into Lawrence of Arabia, but ultimately I think they’ll give this to Lol Crawley for The Brutalist. The ingenuity of filming in VistaVision is sure to win over film nerds everywhere, and the end product looks like a (couple hundred) million bucks.

What should win? Count me among the hypothetical nerds. Of these options, The Brutalist feels most deserving.

What should have been nominated instead? It’s a travesty that Nickel Boys wasn’t nominated for the one category it seemed like an obvious lock to win. Jomo Fray’s first-person filming technique is every bit as clever as Crawley’s bag of tricks, and carries far more emotional weight: This movie is a miracle, and it lives or dies by its cinematography. I can’t rightly drop Maria because I haven’t seen it, so here again I’ll settle for kicking out Emilia Pérez.

Writing (Original Screenplay)

- Anora

- The Brutalist

- A Real Pain

- September 5

- The Substance

What will win? Screenplay awards tend to function as a consolation prize for smaller films. Normally, a Sean Baker indie or offbeat Brady Corbet epic would seem like perfect candidates. But this is a strange year, and Anora and The Brutalist are anything but underdogs. Instead, I think the Academy will award Jesse Eisenberg for A Real Pain.

What should win? If my prediction pans out, the Academy will have made the right choice. A Real Pain flows like a masterful short story; it’s tight, clever, and deserving of the win.

What should have been nominated instead? The Substance was one of my favorite films of the year, but I’d hardly call it tightly written: I was surprised when it won Best Screenplay at Cannes, and I’m doubly surprised to see it here. And The Brutalist, which I loved, struggles in its second half largely due to its screenplay. Meanwhile, September 5 was…fine. Substitute those for The Seed of the Sacred Fig for its deft blending of socio-political metaphor and a psychological thriller, I Saw The TV Glow for fashioning a universe whole cloth and making it emotionally gutting, and Challengers for effortlessly juggling multiple timelines while giving us the single most satisfying callback of the year.

Writing (Adapted Screenplay)

- A Complete Unknown

- Conclave

- Emilia Pérez

- Nickel Boys

- Sing Sing

What will win? Here, I think the Academy’s love of (good!) middlebrow dramas will tip the scales in favor of Peter Straughan for Conclave.

What should win? Sing Sing is my runner-up pick, and in most years it would probably be a lock: It’s cathartic and stirring. But as an act of adaptation, Nickel Boys is astounding on multiple levels. If you’ve read the novel, you probably understand just how difficult it would be to put on screen. RaMell Ross and Joslyn Barnes turn that difficulty into a strength, making the inability to depict certain aspects a thesis of the film. It’s staggeringly clever.

What should have been nominated instead? There was no more radical act of adaptation this year than Vera Drew and Bri LeRose’s The People’s Joker, whose queer reimagining of Batman lore makes the perfect argument for why we continue to rework and repackage existing stories. Throw in Zach Baylin’s screenplay for The Order, which adds surprising complexity to a terrifying true story. Lose Emilia Pérez and A Complete Unknown, both of which lacked the courage of their convictions: Splitting the difference between “easy viewing” and “provocation,” they wound up saying nothing.

Actor In A Supporting Role

- Yura Borisov (Anora)

- Kieran Culkin (A Real Pain)

- Edward Norton (A Complete Unknown)

- Guy Pearce (The Brutalist)

- Jeremy Strong (The Apprentice)

Who will win? People can cry “category fraud” all they want, but running Kieran Culkin in Supporting has clearly paid off: His is the most certain victory of the night.

Who should win? This might be the single strongest category of this year’s Oscars; all five performances are great. But Kieran would also get my vote: He lives up to the hype. (For what it’s worth, I’d argue he does function as a sort of supporting character on steroids: However much screen time he has, the narrative is all about Jesse Eisenberg’s response to, and inability to access, Culkin’s character. Granted, by that logic Timothée Chalamet should also have run in Supporting for A Complete Unknown, which is exactly the sort of trolling Dylan would have approved of.)

Who should have been nominated instead? Again, this is an extremely strong category. But Nicholas Hoult blew me away with his portrayal of a white supremacist in The Order, and all of I Saw The TV Glow hinges on the magnetic pull of Jack Haven’s Maddy. Lose Jeremy Strong and (heretical opinion forthcoming) Edward Norton. If I had three more spots to spare, I’d throw in Mike Faist for Challengers, Mark Eydelshteyn for Anora, and Jason Schwartzman for his hilarious not-technically-Ginsberg-but-I-mean-it’s-kinda-sorta-Ginsberg turn in Queer—but I’ve already cut two worthy contenders, and refuse to shed any more blood.

Actress In A Supporting Role

- Monica Barbaro (A Complete Unknown)

- Ariana Grande (Wicked)

- Felicity Jones (The Brutalist)

- Isabella Rossellini (Conclave)

- Zoe Saldaña (Emilia Pérez)

Who will win? Despite starring in the awards season equivalent of the Hindenburg, Zoe Saldaña still seems poised to take home the win. If the Academy were looking for a safer choice, Ariana Grande would run away with this—and still has a solid chance to. But I think they’ll wait until Wicked: For Good to give G[a]linda her flowers.

Who should win? Look, I want Isabella Rossellini to get a lifetime achievement award as much as the next person, and it’s shocking that this is her first Oscar nom. But Conclave is no Blue Velvet, and as strong as she is in this role, it feels too minor for me to give her the trophy. The cinephile in me wants to award Felicity Jones for her career-best work in The Brutalist, but in truth, I think Ariana Grande has earned this. Comic performances are too often sidelined by the Academy, and hers is as deserving as any I’ve seen in recent memory.

Who should have been nominated instead? The Piano Lesson seems to have been buried by the Netflix algorithm, but Danielle Deadwyler is a force of nature in it as Berniece. Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor also deserves serious attention for her work in Nickel Boys. Swap them for Saldaña (who does solid work given the circumstances, but is still acting in an over-the-top melodrama) and Rossellini (I’m going against the grain with this one, but I just don’t think there’s enough there there).

Actor In A Leading Role

- Adrien Brody (The Brutalist)

- Timothée Chalamet (A Complete Unknown)

- Colman Domingo (Sing Sing)

- Ralph Fiennes (Conclave)

- Sebastian Stan (The Apprentice)

Who will win? It’s a dead heat between Brody and Chalamet, but I give the edge to Timotheé, whose momentum has only grown since his killer appearance on Saturday Night Live. Adrien was also featured on a recent SNL, though I somehow doubt that one’s helping his chances.

Who should win? I’d be more than happy with Brody or Chalamet taking this, and intellectually I’m inclined to give it to Brody. But my heart belongs to Colman Domingo, whose performance in Sing Sing—and facility at matching the energy of first-time actors—feels most worthy of celebration.

Who should have been nominated instead? Sebastian Stan deserves to be here, but they picked the wrong movie: He’s great in The Apprentice, but he’s even better in A Different Man. Keep the name, swap the titles. Then bump Ralph Fiennes, whose excellent work in Conclave still didn’t grab my attention as much as Josh O’Connor did in Challengers. (For the record: I’m calling Zendaya and O’Connor leads, and Faist supporting. Apologies to the relationship anarchy types, but this throuple has a hierarchy).

Actress In A Leading Role

- Cynthia Erivo (Wicked)

- Karla Sofía Gascón (Emilia Pérez)

- Mikey Madison (Anora)

- Demi Moore (The Substance)

- Fernanda Torres (I’m Still Here)

Who will win? The momentum building for Anora could push Mikey Madison over the top, but I expect Demi Moore will retain her lead. Hollywood loves a comeback story, and this one is as juicy as it gets.

Who should win? Fernanda Torres is incredible in I’m Still Here, and Madison has enough charisma to bend an entire movie to her will. But Demi Moore’s turn in The Substance is vulnerable, self-referential, and fearlessly committed. I’ll be thrilled to see her take home the gold.

Who should have been nominated instead? Cynthia Erivo is great as usual, but (plug your ears, theater kids) I just don’t think the character of Elphaba has enough complexity to make for a winning lead performance. And Karla Sofía Gascón charmed my sleep-deprived self well enough at Cannes, but in the sober light of day…she’s gotta go. Trade them for Juliette Gariépy, who is enigmatic and captivating in Red Rooms, and Lily Collias, whose work in Good One is somehow quiet and earth-shattering. (Note: I haven’t been able to catch Hard Truths yet, but by all accounts Marianne Jean-Baptiste is more deserving than any of these nominees.)

Directing

- Jacques Audiard (Emilia Pérez)

- Sean Baker (Anora)

- Brady Corbet (The Brutalist)

- Coralie Fargeat (The Substance)

- James Mangold (A Complete Unknown)

Who will win? It’s a coin toss between Baker/Corbet for Director and Anora/The Brutalist for Picture, but something in me suspects the Academy will spread the wealth this year: Give Director to the more audacious work, and Picture to the bigger crowdpleaser. With that in mind, I’m calling Brady Corbet for the win.

Who should win? I’d love to see Baker or Fargeat take home the gold, but ultimately I agree with the Academy in my head: The Brutalist is Brady Corbet’s singular vision, and the culmination of gallons of blood, sweat, and tears. It’s an achievement that deserves to be championed.

Who should have been nominated instead? Spoilers for the next section, but RaMell Ross directed what I’d consider by far to be the most moving and formally accomplished film of the year with Nickel Boys. He deserves this honor more than anyone. Also throw Luca Guadagnino into the mix for Challengers: I imagine if he’d gone to bat for that instead of Queer this year, he might have made it here himself. Lose Audiard and Mangold, both of whom have made far more deserving movies in the past and will have plenty of chances to do so again.

Best Picture

- Anora

- The Brutalist

- A Complete Unknown

- Conclave

- Dune: Part Two

- Emilia Pérez

- I’m Still Here

- Nickel Boys

- The Substance

- Wicked

What will win? In a year that feels like a tug of war between traditional Oscar fare (A Complete Unknown, Conclave, Emilia Pérez, Wicked) and more challenging cinematic swings (The Brutalist, I’m Still Here, Nickel Boys, The Substance), two films split the difference by being both crowd-pleasing and critically beloved: Anora and Dune: Part Two. And ranked choice voting means there’s a big advantage to straddling both sides of the fence. If you’d told me last summer that this would be the state of things, I’d say Dune: Part Two had it in the bag: It’s a major spectacle, and Denis Villeneuve has been building Hollywood cred for years. But that decidedly isn’t how the year shook out, and the fact that an unapologetic, Palme d’Or-winning tragi-comedy about a sex worker is now the obvious front-runner tells you just how much we’re evolving as a culture. And I say, bring it on. Anora is my bet for Best Picture, and I’ll be cheering when it happens.

What should win? With that said, Anora isn’t my personal preference, even if I’m excited for it to win. Nickel Boys is the more accomplished and the more important work. Unfortunately, I don’t think it stands a chance. As far as the Academy has come, there’s still only so much you can challenge the viewer and take home the top prize. But for what it’s worth, I believe Nickel Boys is the nominee most likely to stand the test of time. A decade from now, audiences will look back and wonder why the hell we slept on a masterpiece.

What should have been nominated instead? If you really want to know my thoughts on this, you can check out my essay about the best films of the year, or the Top 10 list I gave on my podcast. But in the spirit of keeping Best Picture as a combination of populist and artsy fare, I’ll opt for a lighter touch. Lose A Complete Unknown and Wicked, and substitute them for two other star-driven vehicles: Challengers and Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga. Swap out Emilia Pérez with its clumsy attempts at “allyship”, and replace it with the more honest trans expression of I Saw The TV Glow. And if you’re willing to stretch the classic voter just a bit out of their comfort zone, drop one Catholic Church drama for another. Ralph Fiennes is great in Conclave, but have you tried Cillian Murphy in Small Things Like These?

Phew! And with that, I’m calling it a night. Be sure to tune in to tomorrow’s broadcast so you can watch me be wrong in real time.

A case could be made that Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse was the greatest technical triumph in cinema this year. It’s become a standard bit of hyperbole to claim that “every frame could be a painting,” but here it would arguably be damning with faint praise. Given its manic synthesis of visual styles, it’s more accurate to say that every frame could be its own exhibit—variations on a theme by a collective of creators, in conversation with one another but unmistakably distinct. From the pulsing pastels of Spider-Gwen to the zine-inspired anarchy of Spider-Punk, it’s bursting at the seams with visual invention. And like Everything Everywhere All At Once before it, that overstimulation is vital to its emotional core. Miles’ struggle to stay grounded in the face of swirling contradictions rings all too familiar in our present media environment. It’s a feeling best conveyed by way of cacophony.

A case could be made that Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse was the greatest technical triumph in cinema this year. It’s become a standard bit of hyperbole to claim that “every frame could be a painting,” but here it would arguably be damning with faint praise. Given its manic synthesis of visual styles, it’s more accurate to say that every frame could be its own exhibit—variations on a theme by a collective of creators, in conversation with one another but unmistakably distinct. From the pulsing pastels of Spider-Gwen to the zine-inspired anarchy of Spider-Punk, it’s bursting at the seams with visual invention. And like Everything Everywhere All At Once before it, that overstimulation is vital to its emotional core. Miles’ struggle to stay grounded in the face of swirling contradictions rings all too familiar in our present media environment. It’s a feeling best conveyed by way of cacophony. If Spider-Man overwhelmed my visual cortex, The Taste Of Things had other senses on its mind. Tran Anh Hung’s luxurious drama about a gourmand and his muse is as antithetical to Miles’ multiverse as one can get. It’s intimate, unhurried, and obsessively focused. Though the dialogue is technically uttered in French, the characters prefer to speak in a more universal tongue: the love language of food being prepared and enjoyed. Large swaths of runtime are devoted to their passion, most notably a near-wordless half hour sequence in the kitchen. The camera glides through the crowded space, peeping into bubbling pots of stew and lingering on sweaty hunks of veal with voyeuristic intensity. From my vantage point in the front row at the red carpet premiere, the experience was borderline pornographic. Eight months later I still vividly recall a glistening rack of lamb splayed beyond my field of vision, literally too much decadence to take in at once. You never forget your first time. I entered the theater hungry, left positively ravenous, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

If Spider-Man overwhelmed my visual cortex, The Taste Of Things had other senses on its mind. Tran Anh Hung’s luxurious drama about a gourmand and his muse is as antithetical to Miles’ multiverse as one can get. It’s intimate, unhurried, and obsessively focused. Though the dialogue is technically uttered in French, the characters prefer to speak in a more universal tongue: the love language of food being prepared and enjoyed. Large swaths of runtime are devoted to their passion, most notably a near-wordless half hour sequence in the kitchen. The camera glides through the crowded space, peeping into bubbling pots of stew and lingering on sweaty hunks of veal with voyeuristic intensity. From my vantage point in the front row at the red carpet premiere, the experience was borderline pornographic. Eight months later I still vividly recall a glistening rack of lamb splayed beyond my field of vision, literally too much decadence to take in at once. You never forget your first time. I entered the theater hungry, left positively ravenous, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

What could I possibly say about Top Gun: Maverick that hasn’t been said a thousand times? I genuinely don’t know, and I don’t think it matters. If Maverick proves anything, it’s that novelty is overrated. Sometimes you just want the band to play the hits. Sometimes you want to forget about plot, character growth, and troubling geopolitical implications and just ride a roller coaster. Of course it’s running on a pre-ordained track; of course the loops won’t hurt you. But if you throw up your hands and surrender to physics, you’ll feel the adrenaline of actual danger. Tom Cruise pulling off a simulated mission will feel exactly as death-defying as the one with real stakes—it’s all the same forces with the same cheering crowd, it’s all just a matter of perspective. This is the sort of thrill ride you feel in your bones.

What could I possibly say about Top Gun: Maverick that hasn’t been said a thousand times? I genuinely don’t know, and I don’t think it matters. If Maverick proves anything, it’s that novelty is overrated. Sometimes you just want the band to play the hits. Sometimes you want to forget about plot, character growth, and troubling geopolitical implications and just ride a roller coaster. Of course it’s running on a pre-ordained track; of course the loops won’t hurt you. But if you throw up your hands and surrender to physics, you’ll feel the adrenaline of actual danger. Tom Cruise pulling off a simulated mission will feel exactly as death-defying as the one with real stakes—it’s all the same forces with the same cheering crowd, it’s all just a matter of perspective. This is the sort of thrill ride you feel in your bones. Jackass Forever is another movie you feel in your bones, and the primary feeling is pain. There’s a reason my wife didn’t join me in this screening; it’s the same reason I never in a million years thought I’d be putting it on a list. I am nothing like these people. I have never cared about their show. It physically hurts me to watch them! So why did I love it? The best answer I can give is “catharsis.” As we strangers gathered together in the theatre, crying out “OOOOOH” and “NOOOOO”s with the blunt repetition of a pogo stick, all that pain started to feel needed, somehow. A sharp release after two years of dull ache. Hilarious in the way the best nonsense is hilarious: hilarious that we were laughing, hilarious that at 11am on a Saturday in the midst of a still-raging pandemic we’d crawled out of our caves and put on shoes and pants to watch middle-aged men bruise for our amusement. It doesn’t make a lick of sense. It’s also the closest I’ve felt to a stranger in years.

Jackass Forever is another movie you feel in your bones, and the primary feeling is pain. There’s a reason my wife didn’t join me in this screening; it’s the same reason I never in a million years thought I’d be putting it on a list. I am nothing like these people. I have never cared about their show. It physically hurts me to watch them! So why did I love it? The best answer I can give is “catharsis.” As we strangers gathered together in the theatre, crying out “OOOOOH” and “NOOOOO”s with the blunt repetition of a pogo stick, all that pain started to feel needed, somehow. A sharp release after two years of dull ache. Hilarious in the way the best nonsense is hilarious: hilarious that we were laughing, hilarious that at 11am on a Saturday in the midst of a still-raging pandemic we’d crawled out of our caves and put on shoes and pants to watch middle-aged men bruise for our amusement. It doesn’t make a lick of sense. It’s also the closest I’ve felt to a stranger in years. In Emergency, Kunle is striving for respectability, unobtrusiveness. A Nigerian American with Ivy ambitions, he doesn’t rock the boat in his white-dominated university; he keeps his head down and plays by the rules. Whereas his best friend, Sean, is convinced the only move is not to play: Nothing he does will change society’s perception of him as a young Black man in this country. At the start of the film they’re a classic odd couple. Kunle wants to study but Sean wants to drink. Kunle avoids confrontations in class, Sean actively courts them to squeamish effect. But when they come home to find an underage white girl unconscious in their living room, their competing theories of the world are rendered consequential, concrete. If Kunle is right, the social contract demands they contact the police. If Sean is right, that impulse could prove impossibly naive—and dangerous. Are they protagonists in a hijinks-filled raunch-com, or the soon-to-be-victims of a harrowing drama? Eventually, someone needs to choose.

In Emergency, Kunle is striving for respectability, unobtrusiveness. A Nigerian American with Ivy ambitions, he doesn’t rock the boat in his white-dominated university; he keeps his head down and plays by the rules. Whereas his best friend, Sean, is convinced the only move is not to play: Nothing he does will change society’s perception of him as a young Black man in this country. At the start of the film they’re a classic odd couple. Kunle wants to study but Sean wants to drink. Kunle avoids confrontations in class, Sean actively courts them to squeamish effect. But when they come home to find an underage white girl unconscious in their living room, their competing theories of the world are rendered consequential, concrete. If Kunle is right, the social contract demands they contact the police. If Sean is right, that impulse could prove impossibly naive—and dangerous. Are they protagonists in a hijinks-filled raunch-com, or the soon-to-be-victims of a harrowing drama? Eventually, someone needs to choose. The fault lines in Athena couldn’t be more apparent: There’s a physical barricade and two armed, opposing sides. A riot has broken out in the Parisian banlieue, following the murder of a 13-year-old Algerian boy at the (documented) hands of the police. On one side are the rioters, wielding bricks and Molotov cocktails, demanding that justice be served. On the other are the French police, decked head to toe in riot gear, insisting that order be maintained. In the film’s visual vocabulary, this is a war zone. Straddling both armies is Abdel, himself a resident of Athena, a literal soldier and the older brother of the deceased. He’s calling for peace and justice simultaneously. He wants to deescalate the tension, to translate each side to the other, to reason his way to an armistice. But there’s no way to diffuse a lit bomb while preserving its potency: You either neutralize its agency or you support its right to burst. Brimming with anger and raw kinetic energy, Athena is a sprint towards a reckoning.

The fault lines in Athena couldn’t be more apparent: There’s a physical barricade and two armed, opposing sides. A riot has broken out in the Parisian banlieue, following the murder of a 13-year-old Algerian boy at the (documented) hands of the police. On one side are the rioters, wielding bricks and Molotov cocktails, demanding that justice be served. On the other are the French police, decked head to toe in riot gear, insisting that order be maintained. In the film’s visual vocabulary, this is a war zone. Straddling both armies is Abdel, himself a resident of Athena, a literal soldier and the older brother of the deceased. He’s calling for peace and justice simultaneously. He wants to deescalate the tension, to translate each side to the other, to reason his way to an armistice. But there’s no way to diffuse a lit bomb while preserving its potency: You either neutralize its agency or you support its right to burst. Brimming with anger and raw kinetic energy, Athena is a sprint towards a reckoning. Julie wants to understand her mother, Rosalind. It’s at once an act of love and a creative pursuit: Having already mined her own life as inspiration for her films

Julie wants to understand her mother, Rosalind. It’s at once an act of love and a creative pursuit: Having already mined her own life as inspiration for her films Rama doesn’t know Laurence Coly. If her testimony in Saint Omer is to be believed, few people have even noticed Coly since she immigrated from Senegal, let alone known her. But like Julie to her mother, Rama is driven by a creative impulse to try. Hers is less an attempt to connect than it is to solve a terrible puzzle. What would possess this thoughtful speaker, motivated student, and by all accounts loving mother to drown her infant daughter? Played with perfect restraint by Guslagie Malanda, Coly denies the charge of infanticide yet disputes few, if any, details. She walks through her life story patiently, methodically, not wholly devoid of emotion but miscalibrated somehow. It’s as if after years of feeling unseen, she’s forgotten how to reveal herself at all. Was it an act of desperation? Was she in any way coerced? Surely Rama—French-Senegalese herself, a novelist of tragedies, and four months pregnant at the time of this case—can find a “why” that reconciles the mother with her inconceivable actions. Without it, how can she quarantine the horror from her own life? How can any of us?

Rama doesn’t know Laurence Coly. If her testimony in Saint Omer is to be believed, few people have even noticed Coly since she immigrated from Senegal, let alone known her. But like Julie to her mother, Rama is driven by a creative impulse to try. Hers is less an attempt to connect than it is to solve a terrible puzzle. What would possess this thoughtful speaker, motivated student, and by all accounts loving mother to drown her infant daughter? Played with perfect restraint by Guslagie Malanda, Coly denies the charge of infanticide yet disputes few, if any, details. She walks through her life story patiently, methodically, not wholly devoid of emotion but miscalibrated somehow. It’s as if after years of feeling unseen, she’s forgotten how to reveal herself at all. Was it an act of desperation? Was she in any way coerced? Surely Rama—French-Senegalese herself, a novelist of tragedies, and four months pregnant at the time of this case—can find a “why” that reconciles the mother with her inconceivable actions. Without it, how can she quarantine the horror from her own life? How can any of us? Nan Goldin, the subject of All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, has devoted her life to telling stories. Some of those stories are painful; some are provocative; some are glamorizing; some are a disquieting combination of all three. Her goal isn’t to moralize or synthesize, it’s simply to highlight. And for the first hour or so of the film, I have to say I was caught off guard by the approach. Here was a documentary ostensibly about modern day activism and the opioid epidemic, which was spending the bulk of its time depicting the New York club scene of the 70’s and 80’s—reminiscing about an era which seemed at best unrelated to the current crisis, at worst stylistically complicit. Like one of Goldin’s slideshows, the film contextualizes by way of overwhelming. It asks us to sit with the unease until, eventually, connections start to form: between addiction and feeling discarded, between one epidemic and another. What emerges is less a message than an argument by example: You cannot fight what you don’t understand, and you cannot protect by way of euphemism. The messy, unpleasant, often brutal realities of life are our most potent weapons against a power that thrives on contentment. Look at it, before you try to solve it. Look at it, and make it impossible for them to look away.

Nan Goldin, the subject of All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, has devoted her life to telling stories. Some of those stories are painful; some are provocative; some are glamorizing; some are a disquieting combination of all three. Her goal isn’t to moralize or synthesize, it’s simply to highlight. And for the first hour or so of the film, I have to say I was caught off guard by the approach. Here was a documentary ostensibly about modern day activism and the opioid epidemic, which was spending the bulk of its time depicting the New York club scene of the 70’s and 80’s—reminiscing about an era which seemed at best unrelated to the current crisis, at worst stylistically complicit. Like one of Goldin’s slideshows, the film contextualizes by way of overwhelming. It asks us to sit with the unease until, eventually, connections start to form: between addiction and feeling discarded, between one epidemic and another. What emerges is less a message than an argument by example: You cannot fight what you don’t understand, and you cannot protect by way of euphemism. The messy, unpleasant, often brutal realities of life are our most potent weapons against a power that thrives on contentment. Look at it, before you try to solve it. Look at it, and make it impossible for them to look away. The fact that Holy Spider exists at all feels like an act of political protest. A Persian-language procedural which unfolds like a depraved Fincher saga, it puts moral rot on full display and dares us to blink. The most brazen examples come from Saeed, a serial killer who preys on sex workers in the holy city of Mashhad. We open on one of his soon-to-be victims, and we follow until she is no longer living. Nothing, and I mean nothing, is left to the imagination. Saeed’s horrific crimes are being investigated by Arezoo

The fact that Holy Spider exists at all feels like an act of political protest. A Persian-language procedural which unfolds like a depraved Fincher saga, it puts moral rot on full display and dares us to blink. The most brazen examples come from Saeed, a serial killer who preys on sex workers in the holy city of Mashhad. We open on one of his soon-to-be victims, and we follow until she is no longer living. Nothing, and I mean nothing, is left to the imagination. Saeed’s horrific crimes are being investigated by Arezoo Katia and Maurice Krafft love volcanoes. And I can think of no greater compliment than to say that watching Fire of Love made me love them too. Though the documentary includes multiple interviews with the volcanologist couple, its power doesn’t lie in their—or any—words. Rather, it lies in what they saw and preserved. Namely: gorgeous, terrifying, mesmeric footage of volcanoes in the act of erupting. Tiny silhouettes in heat-resistant silver, dwarfed against a skyscraper of magma. Smoke billowing like the fury of some vengeful Greek god. A color palette which has always existed—which is intricately tied with the creation of our world—yet somehow feels futuristic, alien whenever it’s on screen. It’s breathtaking, and at least to this viewer, an entirely novel sensation. By relentlessly pursuing their unorthodox obsessions, the Kraffts accomplished what so many artists aim to do. They made us see the world through their eyes, and see it as glorious.

Katia and Maurice Krafft love volcanoes. And I can think of no greater compliment than to say that watching Fire of Love made me love them too. Though the documentary includes multiple interviews with the volcanologist couple, its power doesn’t lie in their—or any—words. Rather, it lies in what they saw and preserved. Namely: gorgeous, terrifying, mesmeric footage of volcanoes in the act of erupting. Tiny silhouettes in heat-resistant silver, dwarfed against a skyscraper of magma. Smoke billowing like the fury of some vengeful Greek god. A color palette which has always existed—which is intricately tied with the creation of our world—yet somehow feels futuristic, alien whenever it’s on screen. It’s breathtaking, and at least to this viewer, an entirely novel sensation. By relentlessly pursuing their unorthodox obsessions, the Kraffts accomplished what so many artists aim to do. They made us see the world through their eyes, and see it as glorious. In After Yang, the process is even more direct: We literally see the world through Yang’s eyes. When the titular robot becomes unresponsive, his (human) family is left in a state of muted grief. They can talk about solutions (to fix or to replace?) but their sorrow seems to linger on the tip of their tongue. By and large, the film follows their emotional lead: delicate, tentative, lush but only to a point, hovering just on the periphery of heartbreak. All of that changes when, for reasons I won’t spoil, we’re granted access to Yang’s memories. Or rather to his attention—a few seconds per day which Yang deemed worthy of preserving. As we cycle through disconnected fragments of memory, every previously-muted emotion hits with full force. It’s a moving experience, and its meaning has continued to gnaw at me after multiple viewings. Beyond language and rationalization, the most profound mark we leave behind might be the world as we remix it, the particular parts we choose to edit down. Whether a bubbling pool of magma or the perfect cup of tea, we construct the found art of our lives. We forage for beauty and compare notes.

In After Yang, the process is even more direct: We literally see the world through Yang’s eyes. When the titular robot becomes unresponsive, his (human) family is left in a state of muted grief. They can talk about solutions (to fix or to replace?) but their sorrow seems to linger on the tip of their tongue. By and large, the film follows their emotional lead: delicate, tentative, lush but only to a point, hovering just on the periphery of heartbreak. All of that changes when, for reasons I won’t spoil, we’re granted access to Yang’s memories. Or rather to his attention—a few seconds per day which Yang deemed worthy of preserving. As we cycle through disconnected fragments of memory, every previously-muted emotion hits with full force. It’s a moving experience, and its meaning has continued to gnaw at me after multiple viewings. Beyond language and rationalization, the most profound mark we leave behind might be the world as we remix it, the particular parts we choose to edit down. Whether a bubbling pool of magma or the perfect cup of tea, we construct the found art of our lives. We forage for beauty and compare notes. In my

In my  If RRR is a comic book retelling of known revolutionary history, The Woman King is a reimagining of the revolutions that could have been. It’s also an act of historical revelation. The film centers around the Agojie, an all-woman warrior unit who served the 19th century Kingdom of Dahomey in what is now (primarily) Benin. If this is your first time learning that an entirely woman-led fighting force not only existed, but existed for centuries, you aren’t alone: Beyond the bloody action sequences, the film’s most thrilling aspect might be that sense of discovery, excavation. Having established their well-recorded prowess in battle, the film turns its attention to possible points of inflection. What if the Agojie had been allowed to lead, rather than merely serve the King? What if the Kingdom wielded the brunt of its power against the encroaching Portuguese, against the slave trade itself? There are real stories, here, stochastic acts of revolution and revolt that are accumulated into one potent charge. Some view that as revisionistic; I view it as a battle cry. This is what the world could be. It only takes a spark.

If RRR is a comic book retelling of known revolutionary history, The Woman King is a reimagining of the revolutions that could have been. It’s also an act of historical revelation. The film centers around the Agojie, an all-woman warrior unit who served the 19th century Kingdom of Dahomey in what is now (primarily) Benin. If this is your first time learning that an entirely woman-led fighting force not only existed, but existed for centuries, you aren’t alone: Beyond the bloody action sequences, the film’s most thrilling aspect might be that sense of discovery, excavation. Having established their well-recorded prowess in battle, the film turns its attention to possible points of inflection. What if the Agojie had been allowed to lead, rather than merely serve the King? What if the Kingdom wielded the brunt of its power against the encroaching Portuguese, against the slave trade itself? There are real stories, here, stochastic acts of revolution and revolt that are accumulated into one potent charge. Some view that as revisionistic; I view it as a battle cry. This is what the world could be. It only takes a spark. Given the title, you might assume the comfort The Menu is skewering is food. And it is, in a sense—a horror film set at a world-renowned restaurant whose progressive tasting menu grows more violent by the course, it has plenty to say about elitism and dining. But the deepest targets of its ire have nothing to do with eating and everything to do with performance. It’s the Instagram story of the perfectly plated meal, the hallowed Authentic Experience™ fetishized to a commodity. Paying a premium for the bragging right of eating food you likely hate; exclusive membership to a club, password “mouthfeel.” It’s about the way wealth and the pursuit of status hollow you out, strip everything of enjoyment including the act of enjoying something. Like the best satirical comedies, The Menu knows how to execute on precisely what it’s criticizing. It knows how to be highbrow, how to sprinkle in a grace note or witheringly specific dig

Given the title, you might assume the comfort The Menu is skewering is food. And it is, in a sense—a horror film set at a world-renowned restaurant whose progressive tasting menu grows more violent by the course, it has plenty to say about elitism and dining. But the deepest targets of its ire have nothing to do with eating and everything to do with performance. It’s the Instagram story of the perfectly plated meal, the hallowed Authentic Experience™ fetishized to a commodity. Paying a premium for the bragging right of eating food you likely hate; exclusive membership to a club, password “mouthfeel.” It’s about the way wealth and the pursuit of status hollow you out, strip everything of enjoyment including the act of enjoying something. Like the best satirical comedies, The Menu knows how to execute on precisely what it’s criticizing. It knows how to be highbrow, how to sprinkle in a grace note or witheringly specific dig White Noise is based on a major work of postmodern literature; there’s a chance it was assigned to you in college. Yet, perhaps more than any entry on this list, it reads like a critique of our particular decade. Culture has become fragmented and hyper-specific. A rising interest in the

White Noise is based on a major work of postmodern literature; there’s a chance it was assigned to you in college. Yet, perhaps more than any entry on this list, it reads like a critique of our particular decade. Culture has become fragmented and hyper-specific. A rising interest in the  It’s tempting to read Bones and All purely as an allegory. Certainly, it has the raw materials. The queer-coded coming-of-age drama follows young cannibals living in Reagan-era America, whose desires thrust them to the fringes of society. Marked as definitionally “dangerous,” they’re left with no choice but to forge new ways of being. All the beauty, all the bloodshed. What I adore about this film, though, is its refusal to map neatly onto one didactic point. Drown out the social context and consider Maren and Lee on their own terms. They have this passion, this intensity of want they can’t control. It doesn’t just seem dangerous because it violates the social order; it is (in defiance of metaphor) a genuinely violent compulsion, a need to draw blood. They’ve hurt people in the past, and they’re likely to hurt again. Rather than ask us to fully fear them or forgive them, the film simply asks us to feel them. The dull ache of desire and the threat of its fulfillment. The self-loathing that comes after; if only you were stronger. How painful it must be to be at war with yourself. How freeing to lie back in the passenger seat, to peel off the armor, to share in the whole bloody mess. The text of the film is part horror, part tragedy, but the texture is pure romance. It’s love and sex and yearning and danger and self-hatred and -actualization, melded into one intractable feeling. It says “Take me, all of me, exactly as I am.”

It’s tempting to read Bones and All purely as an allegory. Certainly, it has the raw materials. The queer-coded coming-of-age drama follows young cannibals living in Reagan-era America, whose desires thrust them to the fringes of society. Marked as definitionally “dangerous,” they’re left with no choice but to forge new ways of being. All the beauty, all the bloodshed. What I adore about this film, though, is its refusal to map neatly onto one didactic point. Drown out the social context and consider Maren and Lee on their own terms. They have this passion, this intensity of want they can’t control. It doesn’t just seem dangerous because it violates the social order; it is (in defiance of metaphor) a genuinely violent compulsion, a need to draw blood. They’ve hurt people in the past, and they’re likely to hurt again. Rather than ask us to fully fear them or forgive them, the film simply asks us to feel them. The dull ache of desire and the threat of its fulfillment. The self-loathing that comes after; if only you were stronger. How painful it must be to be at war with yourself. How freeing to lie back in the passenger seat, to peel off the armor, to share in the whole bloody mess. The text of the film is part horror, part tragedy, but the texture is pure romance. It’s love and sex and yearning and danger and self-hatred and -actualization, melded into one intractable feeling. It says “Take me, all of me, exactly as I am.” If Maren and Lee find belonging in the open road, Casey is searching for it in an endless, scrolling feed. By the time we meet the protagonist of We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, she’s already formed a truce with her demons. She knows that she’s hurting and she doesn’t expect it to stop. What she wants is to make it be important. To find some audience to connect her pain to something bigger, who can rescue her from the oppressiveness of her isolated teenage life. What they witness is unsettling; I won’t spoil it here. But beyond this film’s horror trappings lies what might be the most perceptive look at modern adolescence since

If Maren and Lee find belonging in the open road, Casey is searching for it in an endless, scrolling feed. By the time we meet the protagonist of We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, she’s already formed a truce with her demons. She knows that she’s hurting and she doesn’t expect it to stop. What she wants is to make it be important. To find some audience to connect her pain to something bigger, who can rescue her from the oppressiveness of her isolated teenage life. What they witness is unsettling; I won’t spoil it here. But beyond this film’s horror trappings lies what might be the most perceptive look at modern adolescence since  Lydia Tár is nobody’s victim. An accomplished conductor, composer, author, and public intellectual, she seems wholly in control of every facet of her life. After all, she fashioned it herself. TÁR is likewise a meticulous construction. In terms of pure craft, I consider it the most flawless entry on my list. The same, however, cannot be said for its namesake. In one early impromptu lecture, we’re given a glimpse of her contradictions. She’s engaging, dynamic, passionate, persuasive, and also patently, toxically wrong. Her arrogance is unwavering and all-consuming. It will take no small force to uproot it. But piece by piece, with virtuosic precision, the film guides us through the movements that will do so. It first asks us to see the world from her eyes, to be hypnotized by her self mythology. Thus calibrated, we—like Lydia—are primed to perceive whatever threatens her position as a mysterious (even supernatural) threat. What else can kill a god, can take down nobody’s victim? The result is slowly unfurling nightmare.

Lydia Tár is nobody’s victim. An accomplished conductor, composer, author, and public intellectual, she seems wholly in control of every facet of her life. After all, she fashioned it herself. TÁR is likewise a meticulous construction. In terms of pure craft, I consider it the most flawless entry on my list. The same, however, cannot be said for its namesake. In one early impromptu lecture, we’re given a glimpse of her contradictions. She’s engaging, dynamic, passionate, persuasive, and also patently, toxically wrong. Her arrogance is unwavering and all-consuming. It will take no small force to uproot it. But piece by piece, with virtuosic precision, the film guides us through the movements that will do so. It first asks us to see the world from her eyes, to be hypnotized by her self mythology. Thus calibrated, we—like Lydia—are primed to perceive whatever threatens her position as a mysterious (even supernatural) threat. What else can kill a god, can take down nobody’s victim? The result is slowly unfurling nightmare. The nightmare in Resurrection is decidedly more literal. Margaret’s tormentor is no hazy manifestation of some inevitable future reckoning. He’s a flesh-and-blood man sitting on a park bench in broad daylight, sharpened canines puncturing a cruel and feral smile. Outwardly, Margaret exists as the epitome of confidence: the high-powered executive who plays her boardroom like a fiddle; the single mother who champions self-sufficiency to a fault. But now he’s clawed his way back from the past to the park bench, and brought with him a host of anxieties. If this sounds like the plot of a demented horror flick—and, spoilers, it absolutely is—it’s also a riveting drama. Over the course of a monologue of Bergman proportions, we watch Margaret peel back every carefully-constructed layer. Her unraveling is too massive to be pigeonholed by genre: She, and the film, defy everything. It’s unnerving to witness someone tear so much away. I have no clue what to make of it; it still lives inside me.

The nightmare in Resurrection is decidedly more literal. Margaret’s tormentor is no hazy manifestation of some inevitable future reckoning. He’s a flesh-and-blood man sitting on a park bench in broad daylight, sharpened canines puncturing a cruel and feral smile. Outwardly, Margaret exists as the epitome of confidence: the high-powered executive who plays her boardroom like a fiddle; the single mother who champions self-sufficiency to a fault. But now he’s clawed his way back from the past to the park bench, and brought with him a host of anxieties. If this sounds like the plot of a demented horror flick—and, spoilers, it absolutely is—it’s also a riveting drama. Over the course of a monologue of Bergman proportions, we watch Margaret peel back every carefully-constructed layer. Her unraveling is too massive to be pigeonholed by genre: She, and the film, defy everything. It’s unnerving to witness someone tear so much away. I have no clue what to make of it; it still lives inside me. Everyone on Inisherin seems to have a different answer. Pádraic is at peace with the smallness of his life and sees contentment as the ultimate aim. The people he loves are his legacy. His sister Siobhán wants to expand her horizons: She hasn’t seen enough of the world to know whom to live for. Then there’s Colm, whose existential crisis serves as The Banshees of Inisherin’s narrative fulcrum. Colm is fine with smallness, with a narrow field of influence. He has no desire to leave the confines of his home. What he can’t stand is that which Pádraic most values: impermanence. Evening pints with buddies, hours in the company of animals, unsung opportunities for kindness. They’re special precisely because they’re intimate, fleeting. But music—music is eternal. Dwarfed by the infinite, Colm’s day-to-day relationships seem like petty distractions. He doesn’t want to be cruel, exactly, but what is the weight of kindness when stacked up against eternal pursuits? If all the kindness of a lifetime were hurled against a door, would it make a sound worth studying like Mozart? A pitch black comedy about the human condition, Banshees refuses to offer up a villain or an answer.

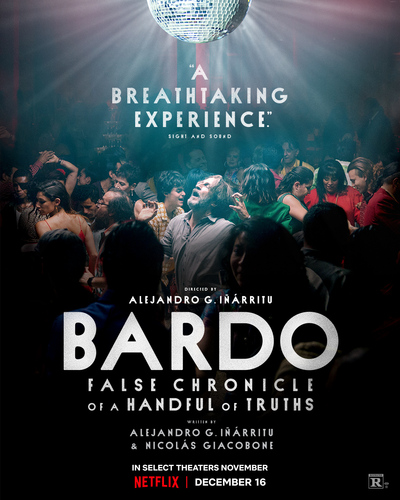

Everyone on Inisherin seems to have a different answer. Pádraic is at peace with the smallness of his life and sees contentment as the ultimate aim. The people he loves are his legacy. His sister Siobhán wants to expand her horizons: She hasn’t seen enough of the world to know whom to live for. Then there’s Colm, whose existential crisis serves as The Banshees of Inisherin’s narrative fulcrum. Colm is fine with smallness, with a narrow field of influence. He has no desire to leave the confines of his home. What he can’t stand is that which Pádraic most values: impermanence. Evening pints with buddies, hours in the company of animals, unsung opportunities for kindness. They’re special precisely because they’re intimate, fleeting. But music—music is eternal. Dwarfed by the infinite, Colm’s day-to-day relationships seem like petty distractions. He doesn’t want to be cruel, exactly, but what is the weight of kindness when stacked up against eternal pursuits? If all the kindness of a lifetime were hurled against a door, would it make a sound worth studying like Mozart? A pitch black comedy about the human condition, Banshees refuses to offer up a villain or an answer. In BARDO, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths, the argument isn’t divvied up between a roving cast of townspeople: Silverio embodies every side at once. The immediacy of family, the permanence of art, the security of a hometown, the tug of new horizons. To further his directorial ambitions, the thinly-veiled Iñáritu surrogate left Mexico City for Los Angeles early in his career. And on paper, the gambit paid off: He is critically acclaimed, his films are widely seen, and his family still lives under one roof. But now, as he prepares a speech for a ceremony held in his honor, he questions every decision. He moved to California to make his art more accessible, but by leaving the city that forged him, has he diluted his own perspective? Is it onanistic to strive for purity, or is it “selling out” to cater to your audience? And who is this audience anyway—pretentious snobs on one extreme, blood-hungry mob on the other. He still knows how to dazzle them, but to what end? Iñáritu still knows how to dazzle us too. Framing Silverio’s inner turmoil as a series of Fellini-esque flights of fancy, his self-critique is nothing if not wildly entertaining. Critics have called it indulgent, but I was bowled over by BARDO’s towering self-awareness

In BARDO, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths, the argument isn’t divvied up between a roving cast of townspeople: Silverio embodies every side at once. The immediacy of family, the permanence of art, the security of a hometown, the tug of new horizons. To further his directorial ambitions, the thinly-veiled Iñáritu surrogate left Mexico City for Los Angeles early in his career. And on paper, the gambit paid off: He is critically acclaimed, his films are widely seen, and his family still lives under one roof. But now, as he prepares a speech for a ceremony held in his honor, he questions every decision. He moved to California to make his art more accessible, but by leaving the city that forged him, has he diluted his own perspective? Is it onanistic to strive for purity, or is it “selling out” to cater to your audience? And who is this audience anyway—pretentious snobs on one extreme, blood-hungry mob on the other. He still knows how to dazzle them, but to what end? Iñáritu still knows how to dazzle us too. Framing Silverio’s inner turmoil as a series of Fellini-esque flights of fancy, his self-critique is nothing if not wildly entertaining. Critics have called it indulgent, but I was bowled over by BARDO’s towering self-awareness Immediately after leaving my screening of Aftersun, I knew it would land in my number one slot

Immediately after leaving my screening of Aftersun, I knew it would land in my number one slot If Aftersun is my personal favorite of the year, Everything Everywhere All at Once is the film which best encapsulates the year. Watching this frenetic multiverse saga feels like living through 2022: overwhelming, oversaturated, tugged in too many directions to move. Evelyn feels it; so does Joy. That temptation to be rendered numb by the enormity of everything, to be swept up in the riptide of

If Aftersun is my personal favorite of the year, Everything Everywhere All at Once is the film which best encapsulates the year. Watching this frenetic multiverse saga feels like living through 2022: overwhelming, oversaturated, tugged in too many directions to move. Evelyn feels it; so does Joy. That temptation to be rendered numb by the enormity of everything, to be swept up in the riptide of

Friendship can flourish in the most unexpected places. In Language Lessons, that place is a video chat. Cariño is a Spanish language teacher based in Costa Rica; Adam lives in Oakland with his wealthy, doting husband, who has gifted him a hundred Spanish lessons. What follows is a charming, minimalist drama about human connection. Adam and Cariño’s relationship is defined by limitation: they have never met in person, know nothing of each other’s histories, and the former’s Spanish vocab is childlike at best. Far from being a hindrance, though, those limits only deepen their connection. Truth by way of brevity. There’s a soulful undercurrent to their early lessons together, the way they fumblingly reveal themselves despite their best intentions. We can feel something personal wriggling to break free, made all the more lovely by the struggle.

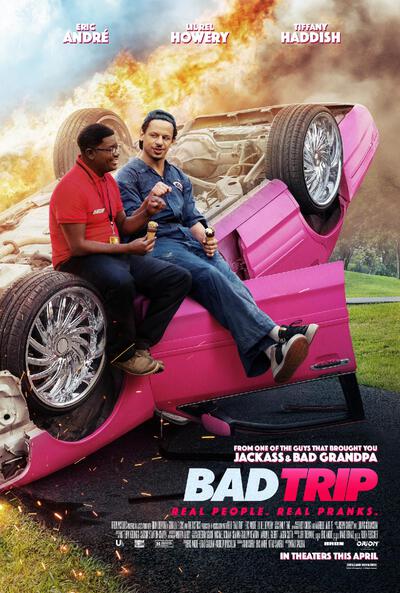

Friendship can flourish in the most unexpected places. In Language Lessons, that place is a video chat. Cariño is a Spanish language teacher based in Costa Rica; Adam lives in Oakland with his wealthy, doting husband, who has gifted him a hundred Spanish lessons. What follows is a charming, minimalist drama about human connection. Adam and Cariño’s relationship is defined by limitation: they have never met in person, know nothing of each other’s histories, and the former’s Spanish vocab is childlike at best. Far from being a hindrance, though, those limits only deepen their connection. Truth by way of brevity. There’s a soulful undercurrent to their early lessons together, the way they fumblingly reveal themselves despite their best intentions. We can feel something personal wriggling to break free, made all the more lovely by the struggle. Bad Trip might strike some as an odd inclusion on this list. A hidden camera prank show wrapped in a zany road trip comedy, it’s about as far removed from “minimalist drama” as you can get. On multiple levels, though, this is an earnest ode to companionship and shared…well, let’s just say experiences. Strip away the hilariously R-rated set-pieces and nonsensical plot machinations, and you’re left with a surprisingly sweet saga about two best friends. But it’s the meta story that really pulled me in. There’s something genuinely communal about watching this: It made me feel present with the cast unlike anything else this year. With its anarchic swerving between reality and fiction, Bad Trip implicates the viewer in every manic escalation and dear-god-don’t-tell-me-they’re-gonna twist. It has the cadence of a joke you had to be there to find funny, and a heart that’s big and silly enough to bring us along for the ride.

Bad Trip might strike some as an odd inclusion on this list. A hidden camera prank show wrapped in a zany road trip comedy, it’s about as far removed from “minimalist drama” as you can get. On multiple levels, though, this is an earnest ode to companionship and shared…well, let’s just say experiences. Strip away the hilariously R-rated set-pieces and nonsensical plot machinations, and you’re left with a surprisingly sweet saga about two best friends. But it’s the meta story that really pulled me in. There’s something genuinely communal about watching this: It made me feel present with the cast unlike anything else this year. With its anarchic swerving between reality and fiction, Bad Trip implicates the viewer in every manic escalation and dear-god-don’t-tell-me-they’re-gonna twist. It has the cadence of a joke you had to be there to find funny, and a heart that’s big and silly enough to bring us along for the ride. Slalom is centered on the perspective of Lyz, a 15-year-old athlete who spends her days training at a remote, Alpine ski academy. She’s independent, motivated, and—under the tutelage of her adult instructor Fred—seems to be on track for greatness.

That sort of internal striving can be its own overwhelming pressure, and Fred amplifies that pressure at every opportunity. But what seems at first blush to be a wintry spin on Whiplash

Slalom is centered on the perspective of Lyz, a 15-year-old athlete who spends her days training at a remote, Alpine ski academy. She’s independent, motivated, and—under the tutelage of her adult instructor Fred—seems to be on track for greatness.

That sort of internal striving can be its own overwhelming pressure, and Fred amplifies that pressure at every opportunity. But what seems at first blush to be a wintry spin on Whiplash The Fallout takes a similarly naturalistic tact in its portrait of a different form of trauma. Vada is an eminently clever junior in high school, whose world is undone by a mass shooting at school. Or at least, her family presumes it’s been undone. After coming down from an initial state of shock, what’s most concerning is just how little she’s changed. She has the same deprecating humor, the same easygoing charm, same self-fulfilling insistence that everything is fine. Like Lyz, her instinctive coping strategy is a fake-it-till-you-make-it brand of strength: accept the situation and keep moving. But while her classmates are divided between putting tragedy in the rear-view and channeling their outrage into activism, Vada’s keep-moving intentions leave her firmly stuck in place. She can’t make forward motion until she’s acknowledged that she’s hurting, but to acknowledge it would shatter the only protective tool she has. What I adore about this film is Vada’s beating heart at its center: a cocktail of irony and sincerity, energy and stasis, which feels remarkably true to this moment. Through her struggle to modulate her outlook while retaining that vulnerable core, we see a glimmer of the adult she’s poised to become. If she’s any indication, we have reason to be hopeful.

The Fallout takes a similarly naturalistic tact in its portrait of a different form of trauma. Vada is an eminently clever junior in high school, whose world is undone by a mass shooting at school. Or at least, her family presumes it’s been undone. After coming down from an initial state of shock, what’s most concerning is just how little she’s changed. She has the same deprecating humor, the same easygoing charm, same self-fulfilling insistence that everything is fine. Like Lyz, her instinctive coping strategy is a fake-it-till-you-make-it brand of strength: accept the situation and keep moving. But while her classmates are divided between putting tragedy in the rear-view and channeling their outrage into activism, Vada’s keep-moving intentions leave her firmly stuck in place. She can’t make forward motion until she’s acknowledged that she’s hurting, but to acknowledge it would shatter the only protective tool she has. What I adore about this film is Vada’s beating heart at its center: a cocktail of irony and sincerity, energy and stasis, which feels remarkably true to this moment. Through her struggle to modulate her outlook while retaining that vulnerable core, we see a glimmer of the adult she’s poised to become. If she’s any indication, we have reason to be hopeful. In Spencer, Princess Diana is dealing with a host of pressures. There’s the overbearing family that police her every move, the vulture-like prowling of the British tabloid press, and the emotionally frigid husband who only makes both matters worse. Over a three-day Christmas visit to their royal estate, she is physically and emotionally trapped. Forced to dress lavishly but never provocatively, to eat indulgently as performance (despite her struggles with food), to pantomime “transparency” without showing a modicum of pain. Hers is a haunted house within a haunted house. She’s holed up in a mansion whose curtains are literally sewn shut, and she can’t escape the confines of her head—an inner voice (and outer Anne Boleyn) that insists her plight is preordained. When she finally does break free of both in service to a miracle, it’s a shared release of tension unlike any I’ve seen this year.

In Spencer, Princess Diana is dealing with a host of pressures. There’s the overbearing family that police her every move, the vulture-like prowling of the British tabloid press, and the emotionally frigid husband who only makes both matters worse. Over a three-day Christmas visit to their royal estate, she is physically and emotionally trapped. Forced to dress lavishly but never provocatively, to eat indulgently as performance (despite her struggles with food), to pantomime “transparency” without showing a modicum of pain. Hers is a haunted house within a haunted house. She’s holed up in a mansion whose curtains are literally sewn shut, and she can’t escape the confines of her head—an inner voice (and outer Anne Boleyn) that insists her plight is preordained. When she finally does break free of both in service to a miracle, it’s a shared release of tension unlike any I’ve seen this year. No paparazzi are spying on the family in The Humans. But as they celebrate Thanksgiving in their daughter’s Chinatown apartment, it’s hard not to feel that same whiff of performance. They are happy to be together; happy to meet the new boyfriend; happy to finally catch up on one another’s lives. When it comes time to communicate, though, everything is strained. Their conversations hit all the usual nerves: political fissures, jabs about finances, closed-minded quips that land with a thud. There are other nerves, too, unspoken relational wounds they seemingly can’t help but pick at. Here, the haunted house aspect is rendered surprisingly literal. Unplaceable noises, flickering lights, clumps of paint and water damage which appear metastatic, looming. The apartment functions both as a symbol of their discomfort and as an active, taunting participant: luring different pairs away from the group, lulling them into a false sense of security, betraying them with its lurches and paper-thin walls.

No paparazzi are spying on the family in The Humans. But as they celebrate Thanksgiving in their daughter’s Chinatown apartment, it’s hard not to feel that same whiff of performance. They are happy to be together; happy to meet the new boyfriend; happy to finally catch up on one another’s lives. When it comes time to communicate, though, everything is strained. Their conversations hit all the usual nerves: political fissures, jabs about finances, closed-minded quips that land with a thud. There are other nerves, too, unspoken relational wounds they seemingly can’t help but pick at. Here, the haunted house aspect is rendered surprisingly literal. Unplaceable noises, flickering lights, clumps of paint and water damage which appear metastatic, looming. The apartment functions both as a symbol of their discomfort and as an active, taunting participant: luring different pairs away from the group, lulling them into a false sense of security, betraying them with its lurches and paper-thin walls. When analyzing the year via the movies it produced, Bo Burnham: Inside almost feels like a cheat. A hybrid comedy special/performance art piece shot and set entirely in the pandemic, communicating “how it felt” is its overriding point. That it communicates it so deftly would, alone, merit inclusion on this list: Scroll through TikTok and find me any other work that so clearly struck a nerve. But what really sets the special apart for me is how well it speaks to the non-pandemic aspects. The character of Bo Burnham (and this is very much a character) lives in a world that is somehow post -irony and -sincerity. Overwhelmed by an amalgamation of contradictory inputs, the quickest way to express the truth is to present competing versions: the backlash to the backlash to the thing that’s just begun. He’s rendered impotent by excess, too clever not to undercut every attempt at honest sentiment, too consumed by anxious energy to resist attempting it regardless. He wants to make comedy, but comedy is inherently egocentric. He wants to verbalize the rot at the heart of Internet-era culture, but he is a shareholder in and influencer of that culture. A confessional style is masturbatory and a failure to confess is wrong; apathy’s a tragedy and boredom is a crime. And so he spirals ever deeper into his bespoke, relentless Everything, shedding casual bits of brilliance as he goes.