Movies about parenting are a dime a dozen. Good movies about parenting…less so. The bulk of that disconnect is likely driven by market forces: like pet ownership, faith, or military service (talking coming-home stories, not war flicks, here), there’s a built-in audience just begging to be catered to. It isn’t that nuance can’t exist — plenty of wonderful films tackle said subjects, at least peripherally — it’s just that it’s rarely profitable. People want to see themselves reflected on the big screen, and it’s far more safe to reflect something overtly flattering. Think broad zany comedies about the chaos of child rearing, capped with some what-a-blessing-this-is melodramatic finale. Think Josh Duhamel drowning in a ball pit full of diapers; think Katherine Heigl in, well, pretty much anything.

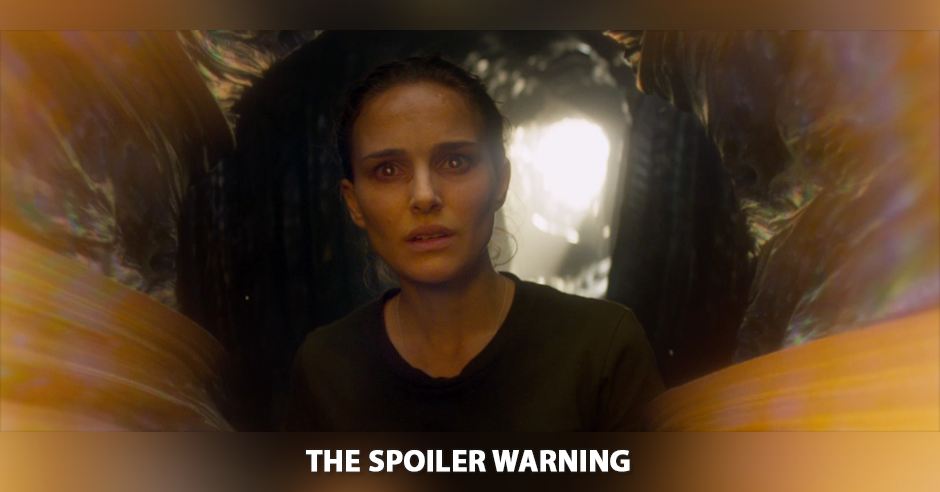

What surprises me about Tully (4.5/5), written by Diablo Cody and directed by Jason Reitman, isn’t that it avoids those cliches. Their past collaborations (Juno, Young Adult) set clear expectations on that front (to say nothing of Reitman’s recent, more standoffish work). It isn’t that they’re willing to alienate an audience with an unflattering reflection. It’s that, even while showing such a complex / difficult portrait, they manage to be truly generous to that same demographic. This is a gentle film; a tender, welcoming one. And it is, by my estimation, the most mature work (which isn’t to say the “best”) of all key players to date — not just of Cody and Reitman, but of the actress who carries it. Charlize Theron is, typically, outstanding here, and that has almost nothing to do with “bravery” or “physical transformations.” It’s her pitch-perfect ability to, somehow, emote cynicism and vulnerability in the same breath. While the trailer comes off as “Young Adult 2: Mo Baby Mo Problems”, her portrayal couldn’t be more different. She’s witty, as usual, and tends to be a megaphone for Diablo Cody’s barbs, but they’re never delivered with a wink to an audience. She’s hurting, frequently, but it’s a wound she opens for our inspection. She’s the embodiment of exactly the tightrope walk the script is pulling off: between cleverness and sincerity, between jadedness and feeling.

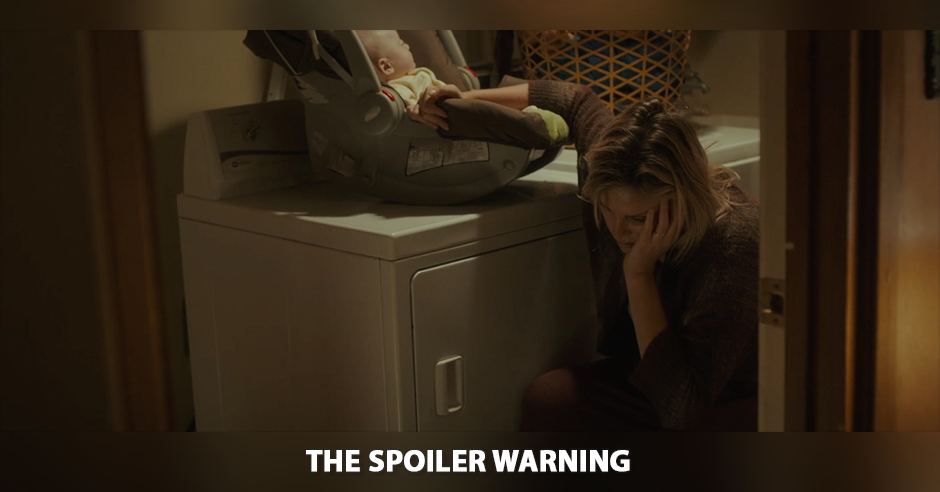

Marlo has two school-aged children and a newborn in tow. She’s overworked, stressed, and constantly tired. She’s primarily tired of working alone. Her husband, Drew (Ron Livingston), isn’t a bad guy per se. He wants to help in the same sense that your puppy wants to help you through your impending divorce — earnest in feeling, but lacking the emotional IQ. Enter Tully, the 20something night nurse her brother hired as a present. “Night nurse” means, from the hours of ~10pm till ~7am, she takes care of everything: watching the baby, cleaning the house, waking Marlo up to feed in the comfort of her bed. She’s quirky, self-assured, and almost infuriatingly perfect. She’s also a godsend. I won’t give away the third act (and don’t suggest you try and predict it), so I can’t say much more about the plot. All I’ll say is watching Marlo’s transformation, even after just a few hours of comfort and rest, was so heartwarming — so powerful — that the film could have ended virtually anywhere and left me satisfied. It’s one of those movies that manages to be just about everything: laugh-out-loud funny, quietly moving, audacious in bursts, reserved in others. It’s a kind, human portrait, and I honestly can’t imagine a single person being disappointed in it. You should see this when it hits theatres in a few weeks, and read as little about it before as humanly possible.

Listening to our spoiler-free review doesn’t count, though! Chris and I talk Up In The Air, emotional arcs, and dropping iPhones on babies’ faces in our first of many Tribeca Film Festival episodes.