tl;dr: here’s a list with no explanations

Things I wanted to see but haven’t yet: Selma (Update: Review Here), American Sniper (Update: Review Here), Two Days One Night (Update: it might have placed in the #10 category), Mr. Turner, Nymphomaniac, Still Alice, Winter Sleep, Goodbye to Language 3D

You can hear my friends and I discuss our lists at: The Spoiler Warning Podcast. You can also find more reviews at my Letterboxd page.

Meandering Intro

Ignoring a few edge cases (“What if it technically hit the festival circuit in 2013?”, “Do I count stand-up specials like Flickchart does?”) I saw 77 movies that came out last year. 71 if you want to be all conservative about it. And despite occasionally seeing terrible things for the sake of the podcast (here’s looking at you, Exodus), I rarely chose to watch garbage: most were actually pretty decent. Maybe 50 were solid enough to recommend to a friend; 15 or 20 I loved without reservation. But that love was often complicated. Maybe it’s just been an odd year for movies, or maybe I’m the one who’s changing.

2013 was full of “Stephen classics”: the intimate, heartfelt indie; the little guy you loved discovering and loved loving. Short Term 12, Her, Before Midnight, The Spectacular Now, Kings of Summer, The Way Way Back, Frances Ha. They were well-done works in their own right, but the thing that lingered wasn’t their quality so much as their soul: I was emotionally invested in the characters.

2014 would have been a depressing year without at least a few of those, but the leaders of the pack –- the things that truly stuck with me — were rarely warm and cozy. Which isn’t to say they weren’t emotionally resonant: it just wasn’t their ultimate point. More often the point was a total experience: to leave you overwhelmed, exhausted, thrilled, or lost in thought. This year was all about movies which defined their own rhythm and just started drumming; which pulled me in and said “This is what we’re going to do for the next two hours, deal with it.” “Visceral” trumped “sentimental” nearly every time.

For my 1-5 choices, I let that “wow” factor drive me: it didn’t matter if it was a charming underdog or had any sort of emotional anchor, it mattered how much it shook me. For 6-10 I wanted to represent a bit more variety, so I let myself be swayed by broader considerations. To avoid the impossible task of whittling those down to 5 slots, I decided to cheat and give each a named “award” category, with winners and honorable mentions. Taken as an ordered list (comprised only of winners, where #10 > any runner up) I’d stand by it, but my feelings are fuzzier than that. Finally, I’ll throw in a few misc categories which defied ranking, but really deserved mention.

1-5: The “Wow Factor”

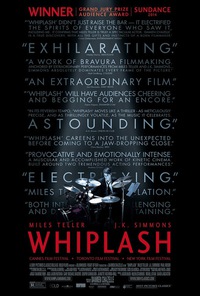

1. Whiplash

From the moment I left the theatre, I knew it would take an act of God to shake Whiplash (full review) from my #1 slot. While the others may have been more masterful or accomplished, nothing packed a gut punch remotely this sharp. J.K. Simmons and Miles Teller are absolutely terrific in their roles as abusive teacher and obsessive student, and the feelings they channel (a paradoxical blend of anxiety and joy, fear and admiration) are devastating. It packed more intensity into a single drum beat than all the explosions in Fury, and that intensity – squeezed through a restrained staccato pinhole – was as terrifying as it was thought-provoking and exhilarating. The final scene alone would have qualified this as my top choice of the year: that the rest of the film was brilliant is just icing.

From the moment I left the theatre, I knew it would take an act of God to shake Whiplash (full review) from my #1 slot. While the others may have been more masterful or accomplished, nothing packed a gut punch remotely this sharp. J.K. Simmons and Miles Teller are absolutely terrific in their roles as abusive teacher and obsessive student, and the feelings they channel (a paradoxical blend of anxiety and joy, fear and admiration) are devastating. It packed more intensity into a single drum beat than all the explosions in Fury, and that intensity – squeezed through a restrained staccato pinhole – was as terrifying as it was thought-provoking and exhilarating. The final scene alone would have qualified this as my top choice of the year: that the rest of the film was brilliant is just icing.

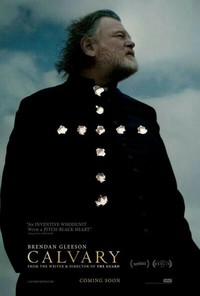

2. Calvary

Of all my top choices, this is by far the one dearest to my heart; which also makes it the least likely to be universal. I was so blown away by my first viewing of Calvary (full review) that I’ve purposely avoided watching it again, lest hindsight ruin the memory. In another life, I might criticize it for pretension: the whole film reads like an extended play, a Waking Life-esque outlet for John Michael McDonagh to muse about faith in a postmodern world. But the film absolutely demands otherwise. Where most treatments of religion either become pandering trainwrecks (Saving Christmas) or exercises in unbridled cynicism (Religulous), Calvary is both piercing and respectful, pitch-black but somehow gentle. It’s far too skeptical to satisfy the fundamentalist audience, and too empathetic to elicit “take-down” appeal. The tightrope it walks instead, rendered effortless by Gleeson’s world-weary gaze, is the closest thing to “wisdom” I’ve seen on film in a very long time.

Of all my top choices, this is by far the one dearest to my heart; which also makes it the least likely to be universal. I was so blown away by my first viewing of Calvary (full review) that I’ve purposely avoided watching it again, lest hindsight ruin the memory. In another life, I might criticize it for pretension: the whole film reads like an extended play, a Waking Life-esque outlet for John Michael McDonagh to muse about faith in a postmodern world. But the film absolutely demands otherwise. Where most treatments of religion either become pandering trainwrecks (Saving Christmas) or exercises in unbridled cynicism (Religulous), Calvary is both piercing and respectful, pitch-black but somehow gentle. It’s far too skeptical to satisfy the fundamentalist audience, and too empathetic to elicit “take-down” appeal. The tightrope it walks instead, rendered effortless by Gleeson’s world-weary gaze, is the closest thing to “wisdom” I’ve seen on film in a very long time.

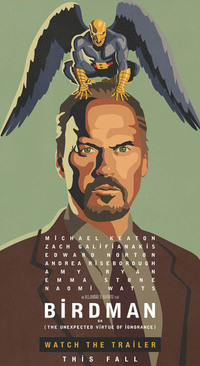

3. Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)

Birdman (full review) is about theatre, but what it ultimately amounts to is a magic show. Walking into the cinema, everything in me was ready to hate it – its hip meta-irony, self-satisfied winks at the camera, empty satire which would probably elicit zero laughs but somehow be praised by Merlot-sipping critics as “hilariously droll.” Then it started: the off-kilter percussion, the incredible sense of urgency, the camerawork which quite literally soars. In minutes it had established a visual language and world wholly unique to itself, commanding my attention in a way that nothing else this year has. With singular style and a inexplicable immediacy, it converted me by force. I was blown away.

Birdman (full review) is about theatre, but what it ultimately amounts to is a magic show. Walking into the cinema, everything in me was ready to hate it – its hip meta-irony, self-satisfied winks at the camera, empty satire which would probably elicit zero laughs but somehow be praised by Merlot-sipping critics as “hilariously droll.” Then it started: the off-kilter percussion, the incredible sense of urgency, the camerawork which quite literally soars. In minutes it had established a visual language and world wholly unique to itself, commanding my attention in a way that nothing else this year has. With singular style and a inexplicable immediacy, it converted me by force. I was blown away.

4. Boyhood

I’ve debated so much where, or whether, to include this. Strictly in terms of narrative, it’s doubtful that Boyhood (full review) deserves a spot this high: my love for it is as much due to the story surrounding it as it is the art itself, which, stripped of truth, might well play like a 3 hour episode of Parenthood. The same could be said about Linklater’s Before series, where the magic of recurrence can imbibe even the smallest, most lifelike conversations with depth. But I love those films, for all their perceived preciousness, and I absolutely love Boyhood too. In terms of “film as event” it stands peerless: it’s a feat of cinema and a necessarily rare spectacle. It carried with it the magic of growing up, the bittersweet loss of setting aside childish things, and a sense of incidental nostalgia which would feel forced in any other context. Which is the ultimate irony here. The story surrounding the film allows it a sort of unfiltered, heart-on-your-sleeve sentiment which would make me groan in any traditional coming-of-age story; but it’s exactly that unfiltered sentiment that makes it so hard-hitting and beautiful. Embrace the unfair advantage. Boyhood was wonderful.

I’ve debated so much where, or whether, to include this. Strictly in terms of narrative, it’s doubtful that Boyhood (full review) deserves a spot this high: my love for it is as much due to the story surrounding it as it is the art itself, which, stripped of truth, might well play like a 3 hour episode of Parenthood. The same could be said about Linklater’s Before series, where the magic of recurrence can imbibe even the smallest, most lifelike conversations with depth. But I love those films, for all their perceived preciousness, and I absolutely love Boyhood too. In terms of “film as event” it stands peerless: it’s a feat of cinema and a necessarily rare spectacle. It carried with it the magic of growing up, the bittersweet loss of setting aside childish things, and a sense of incidental nostalgia which would feel forced in any other context. Which is the ultimate irony here. The story surrounding the film allows it a sort of unfiltered, heart-on-your-sleeve sentiment which would make me groan in any traditional coming-of-age story; but it’s exactly that unfiltered sentiment that makes it so hard-hitting and beautiful. Embrace the unfair advantage. Boyhood was wonderful.

5. Inherent Vice

Inherent Vice is an inherently un-Stephen film. Like Anderson’s The Master, it eschews traditional narrative and emotional anchors outright: it had zero interest in holding my hand. But where I found The Master dry and distant, Inherent Vice was a joy to behold. With a distinct sense of time and place, unquestioning style, and a sprawling plot which would only be called “massive”, it left me in a daze. Phoenix is perfectly good as straight-man Doc, but it’s the zany characters in his orbit that really make the film: Martin Short as the drug-dealing dentist, Josh Brolin the repressed bully/manchild policeman, Katherine Waterston the ephemeral femme fatale, and MVP Joanna Newsom the remarkably warm narrator. It’s The Big Lebowki’s laid-back haze injected with Burn After Reading’s self-aware intensity: a period piece, a comedy, and a bizarre fever dream. There’s nothing quite like it.

Inherent Vice is an inherently un-Stephen film. Like Anderson’s The Master, it eschews traditional narrative and emotional anchors outright: it had zero interest in holding my hand. But where I found The Master dry and distant, Inherent Vice was a joy to behold. With a distinct sense of time and place, unquestioning style, and a sprawling plot which would only be called “massive”, it left me in a daze. Phoenix is perfectly good as straight-man Doc, but it’s the zany characters in his orbit that really make the film: Martin Short as the drug-dealing dentist, Josh Brolin the repressed bully/manchild policeman, Katherine Waterston the ephemeral femme fatale, and MVP Joanna Newsom the remarkably warm narrator. It’s The Big Lebowki’s laid-back haze injected with Burn After Reading’s self-aware intensity: a period piece, a comedy, and a bizarre fever dream. There’s nothing quite like it.

6-10: Awards: Winners and (Noteworthy) Runners Up

6. Dallas Buyers Club Award: Nightcrawler, w/ Gone Girl and The Imitation Game

This award is for films which were conventionally great: they didn’t break new ground in form or style, but were flawlessly executed from start to finish. The winner, Nightcrawler (full review), was a riveting thriller about LA crime journalism, propelled by a twisted sense of triumph, a romantic eye for the dark open road, and a transformative performance by Jake Gyllenhaal. Runner up Gone Girl (full review) was an excellent slow-burning thriller in its own right, with boatloads of style if only slightly less substance than I would have liked. The Imitation Game (full review) was an extremely solid biopic, telling an important story with urgency and wit.

This award is for films which were conventionally great: they didn’t break new ground in form or style, but were flawlessly executed from start to finish. The winner, Nightcrawler (full review), was a riveting thriller about LA crime journalism, propelled by a twisted sense of triumph, a romantic eye for the dark open road, and a transformative performance by Jake Gyllenhaal. Runner up Gone Girl (full review) was an excellent slow-burning thriller in its own right, with boatloads of style if only slightly less substance than I would have liked. The Imitation Game (full review) was an extremely solid biopic, telling an important story with urgency and wit.

7. Annie Hall Award: Listen Up Philip, w/ Love Is Strange and The Grand Budapest Hotel

This award is for comfortable, low-stakes films which, while not exceptionally daring, were pitch-perfect in their respective genre. With its distinctly New York vibe and infectious DIY aesthetic, Listen Up Philip was the clear winner: it took inherently unlikable characters and, somehow, created something charming, empathetic, and warm. While Jason Schwartzman was good as the titular Philip, the true scene-stealer was Elizabeth Moss, who blew me away in her own small, genuine way. Love Is Strange looked like it would be pure Oscar bait, but the leads (John Lithgow and Alfred Molina) were too convincing to ever feel precious: they conveyed a particular brand of loneliness (realizing you’ve become a burden on the people who love you) with ease and grace, and the New York it presents is a joy to get lost in. Grand Budapest Hotel (full review) was, like virtually every Wes Anderson film, impossible not to love: zany, playful, distinct. At the beginning of the year I would have easily expected this to make my list – it’s delightful.

This award is for comfortable, low-stakes films which, while not exceptionally daring, were pitch-perfect in their respective genre. With its distinctly New York vibe and infectious DIY aesthetic, Listen Up Philip was the clear winner: it took inherently unlikable characters and, somehow, created something charming, empathetic, and warm. While Jason Schwartzman was good as the titular Philip, the true scene-stealer was Elizabeth Moss, who blew me away in her own small, genuine way. Love Is Strange looked like it would be pure Oscar bait, but the leads (John Lithgow and Alfred Molina) were too convincing to ever feel precious: they conveyed a particular brand of loneliness (realizing you’ve become a burden on the people who love you) with ease and grace, and the New York it presents is a joy to get lost in. Grand Budapest Hotel (full review) was, like virtually every Wes Anderson film, impossible not to love: zany, playful, distinct. At the beginning of the year I would have easily expected this to make my list – it’s delightful.

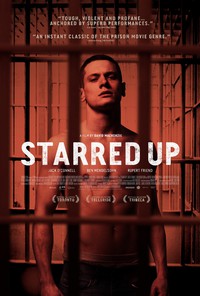

8. Whiplash Award: Starred Up, w/ Blue Ruin

If Whiplash hadn’t been my number 1 it would have handily won this award, reserved for small films which packed a disproportionately large, dizzying punch. As is, the honor goes to Starred Up (full review), a British prison drama carried by Jack O’Connel’s intense, almost unbearably difficult, portrayal of a young inmate. He brings with him a potent combination of frightening possibility and good intent, repressed anger lurking beneath every scene. It’s a powerhouse performance, the likes of which I haven’t seen since Keith Stanfield as Short Term 12’s “Marcus” (if you know my love for that film, you know how big a compliment that is.) Runner up was Blue Ruin, an unflinching, whirlwind anti-revenge fantasy set in the deep south. It’s a small, somewhat cryptic film, but carries more grizzly excitement than any big-budget thriller I saw this year.

If Whiplash hadn’t been my number 1 it would have handily won this award, reserved for small films which packed a disproportionately large, dizzying punch. As is, the honor goes to Starred Up (full review), a British prison drama carried by Jack O’Connel’s intense, almost unbearably difficult, portrayal of a young inmate. He brings with him a potent combination of frightening possibility and good intent, repressed anger lurking beneath every scene. It’s a powerhouse performance, the likes of which I haven’t seen since Keith Stanfield as Short Term 12’s “Marcus” (if you know my love for that film, you know how big a compliment that is.) Runner up was Blue Ruin, an unflinching, whirlwind anti-revenge fantasy set in the deep south. It’s a small, somewhat cryptic film, but carries more grizzly excitement than any big-budget thriller I saw this year.

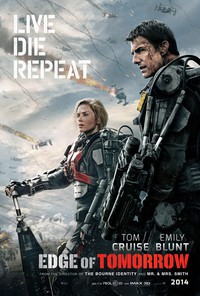

9. Stephen Isn’t As Snobby As Commenters Say He Is, Sometimes He Likes Stuff People Actually Saw Award: Edge of Tomorrow, w/ The Lego Movie, Guardians of the Galaxy, 22 Jump Street, and Big Hero 6

There’s a distinct possibility that no one saw any of the movies I mentioned so far. That’s partly my own bias: smaller films tend to take bigger risks, and bigger risks often yield bigger payoffs. But this was also a great year for creative blockbusters, which have the difficult task of being both uncompromising and crowd-pleasing. They deserve all the love they’ve received, and then some. The winner, Edge of Tomorrow (full review), took a clever Sci-Fi conceit and executed it with the perfect balance of whimsy and thrill. Tom Cruise is genuinely awesome in it. The Lego Movie (full review) was manic and wonderful, an ostensibly “kids’” movie with a sharper point of view than most “thinky” flicks that came out. Guardians Of The Galaxy (full review) was an unabashedly silly, campy adventure, which proves that the superhero craze doesn’t need to signify creative bankruptcy. 22 Jump Street (full review) was a hilarious buddy-cop joyride, with a clever, self-referential script that should put most of the raunch-com genre to shame. Big Hero 6 (full review) was everything I could want in a kids’ movie: sincere, playful, and endlessly inventive. Convincing kids that nothing could be cooler than “Bay Area robotics researcher” didn’t hurt, either…

There’s a distinct possibility that no one saw any of the movies I mentioned so far. That’s partly my own bias: smaller films tend to take bigger risks, and bigger risks often yield bigger payoffs. But this was also a great year for creative blockbusters, which have the difficult task of being both uncompromising and crowd-pleasing. They deserve all the love they’ve received, and then some. The winner, Edge of Tomorrow (full review), took a clever Sci-Fi conceit and executed it with the perfect balance of whimsy and thrill. Tom Cruise is genuinely awesome in it. The Lego Movie (full review) was manic and wonderful, an ostensibly “kids’” movie with a sharper point of view than most “thinky” flicks that came out. Guardians Of The Galaxy (full review) was an unabashedly silly, campy adventure, which proves that the superhero craze doesn’t need to signify creative bankruptcy. 22 Jump Street (full review) was a hilarious buddy-cop joyride, with a clever, self-referential script that should put most of the raunch-com genre to shame. Big Hero 6 (full review) was everything I could want in a kids’ movie: sincere, playful, and endlessly inventive. Convincing kids that nothing could be cooler than “Bay Area robotics researcher” didn’t hurt, either…

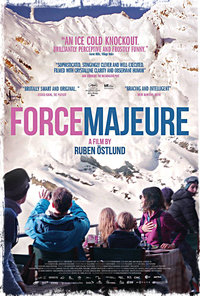

10. Take the Premise and Run Award: Force Majeure, w/ The One I Love

This award (misleadingly named the “Charlie Kaufman Award” on the podcast) goes to a film whose central premise, while simple, was so fresh and thought-provoking that even if it had been sloppily executed, it would have stuck with me. The One I Love (full review) was an excellent example: cryptically billed as a relationship comedy, it hinges on a single (massive, secret) twist, gives it time to sink in, then takes it to its logical conclusion. If it were somehow possible to adapt it for the stage, I can imagine it being amazing: it’s got that sort of elegant construction. While the script sometimes lagged, the concept was strong enough to win me over full-stop. However, my personal winner (which Chris will hate me for) has to be Force Majeure, a Swedish comedy which presents a pivotal event in a couple’s relationship, then sits back and lets that relationship slowly unravel. On premise alone it’s admittedly treading on established ground (The Loneliest Planet did it a couple years ago), but the execution of said premise, with its balance of exaggerated satire and awkward realism, made it rise above the competition. And though the award is about premise, it’d be a shame not to mention its distinct visual style, employing wide angle shots that frequently lose its subjects amidst magnificent, blinding white slopes. The unhurried pace might frustrate some viewers, but if you like your movies with a little breathing room, this one is well worth the investment.

This award (misleadingly named the “Charlie Kaufman Award” on the podcast) goes to a film whose central premise, while simple, was so fresh and thought-provoking that even if it had been sloppily executed, it would have stuck with me. The One I Love (full review) was an excellent example: cryptically billed as a relationship comedy, it hinges on a single (massive, secret) twist, gives it time to sink in, then takes it to its logical conclusion. If it were somehow possible to adapt it for the stage, I can imagine it being amazing: it’s got that sort of elegant construction. While the script sometimes lagged, the concept was strong enough to win me over full-stop. However, my personal winner (which Chris will hate me for) has to be Force Majeure, a Swedish comedy which presents a pivotal event in a couple’s relationship, then sits back and lets that relationship slowly unravel. On premise alone it’s admittedly treading on established ground (The Loneliest Planet did it a couple years ago), but the execution of said premise, with its balance of exaggerated satire and awkward realism, made it rise above the competition. And though the award is about premise, it’d be a shame not to mention its distinct visual style, employing wide angle shots that frequently lose its subjects amidst magnificent, blinding white slopes. The unhurried pace might frustrate some viewers, but if you like your movies with a little breathing room, this one is well worth the investment.

Misc Awards / Defied Ranking

The Act of Killing Award: Three-way tie between The Missing Picture, Jodorowsky’s Dune, and Mistaken for Strangers w/ runner up Life Itself

It’s impossible for me to rank documentaries against works of fiction, as I learned with last year’s The Act Of Killing — it may have been the most striking thing I’d seen in years, but how could I possibly compare it against a romantic comedy? I can’t bring myself to try, but these three films could go head-to-head with the best of my list. The Missing Picture was a heartbreaking look at the Cambodian genocide under the Khmer Rouge. Like the eponymous Act of Killing and excellent Waltz With Bashir, its narrator used a creative outlet to share unfilmable memories: in this case, acting out the attrocities with small, hand-engraved figurines. Like those documentaries, it is both devastating and hopeful, its darkest scenes frequently intercut with gorgeous flights of fancy. It’s a story about the triumph of the human spirit, and it’s truly beautiful. On the other end of the spectrum, Jodorowsky’s Dune is by far the most fun I’ve had with a documentary in recent years. The film, which centers around a movie that never got made, is a joy to behold: it’s bizarre, visually stunning, and a celebration of the indomitable creative spirit. Perhaps the most surprising was Mistaken For Strangers, which ostensibly begins as a tour documentary but ends as a deeply personal look at jealousy and sibling dynamics. If you told me a documentary about The National would almost make me tear up, I’d probably laugh at you. But I’d be wrong. Life Itself didn’t quite reach those heights, but it came close: the chance to see Roger Ebert tell his own story, mere weeks before his passing, is a gift to the film community. As a work of art it was pretty modest, but as a tribute to a lost icon it’s essential.

It’s impossible for me to rank documentaries against works of fiction, as I learned with last year’s The Act Of Killing — it may have been the most striking thing I’d seen in years, but how could I possibly compare it against a romantic comedy? I can’t bring myself to try, but these three films could go head-to-head with the best of my list. The Missing Picture was a heartbreaking look at the Cambodian genocide under the Khmer Rouge. Like the eponymous Act of Killing and excellent Waltz With Bashir, its narrator used a creative outlet to share unfilmable memories: in this case, acting out the attrocities with small, hand-engraved figurines. Like those documentaries, it is both devastating and hopeful, its darkest scenes frequently intercut with gorgeous flights of fancy. It’s a story about the triumph of the human spirit, and it’s truly beautiful. On the other end of the spectrum, Jodorowsky’s Dune is by far the most fun I’ve had with a documentary in recent years. The film, which centers around a movie that never got made, is a joy to behold: it’s bizarre, visually stunning, and a celebration of the indomitable creative spirit. Perhaps the most surprising was Mistaken For Strangers, which ostensibly begins as a tour documentary but ends as a deeply personal look at jealousy and sibling dynamics. If you told me a documentary about The National would almost make me tear up, I’d probably laugh at you. But I’d be wrong. Life Itself didn’t quite reach those heights, but it came close: the chance to see Roger Ebert tell his own story, mere weeks before his passing, is a gift to the film community. As a work of art it was pretty modest, but as a tribute to a lost icon it’s essential.

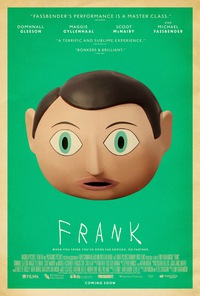

Vintage Stephen Award: Frank, w/ Obvious Child and Skeleton Twins

While they weren’t quite striking enough to rank, it’s worth mentioning that there were still plenty of movies which captured the intimate, “indie” spirit I normally gravitate towards. The winner, Frank (full review), is an excellent (and unabashedly odd) look at the creative process, and the mystique that can both inform and obscure it. Obvious Child managed to squeeze a heartfelt rom-com out of an extremely difficult subject, which despite its imperfections is no small feat. Skeleton Twins (full review) similarly took a dark subject and made it very funny: the charisma of its leads was infectious.

While they weren’t quite striking enough to rank, it’s worth mentioning that there were still plenty of movies which captured the intimate, “indie” spirit I normally gravitate towards. The winner, Frank (full review), is an excellent (and unabashedly odd) look at the creative process, and the mystique that can both inform and obscure it. Obvious Child managed to squeeze a heartfelt rom-com out of an extremely difficult subject, which despite its imperfections is no small feat. Skeleton Twins (full review) similarly took a dark subject and made it very funny: the charisma of its leads was infectious.

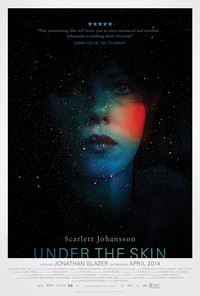

Tree of Life Award: Under the Skin, w/ Only Lovers Left Alive

Sometimes I can respect a movie’s vision while not personally loving the outcome. With striking imagery and a haunting score, Under the Skin was likely the most stunning sensory experience of the year. The guerilla-style filmmaking and socially resonant topic (the male gaze, expectations on women) gives me huge respect for the creator. It left me a bit cold, but I can see myself loving it in a properly calibrated second watch. Runner up Only Lovers Left Alive gave a shot of originality to a done-to-death vampire genre, turning it into a stirring think piece about art and culture. While the pace was a little too slow to pull me in, in time I can see it lingering long after most of these other films have faded.

Sometimes I can respect a movie’s vision while not personally loving the outcome. With striking imagery and a haunting score, Under the Skin was likely the most stunning sensory experience of the year. The guerilla-style filmmaking and socially resonant topic (the male gaze, expectations on women) gives me huge respect for the creator. It left me a bit cold, but I can see myself loving it in a properly calibrated second watch. Runner up Only Lovers Left Alive gave a shot of originality to a done-to-death vampire genre, turning it into a stirring think piece about art and culture. While the pace was a little too slow to pull me in, in time I can see it lingering long after most of these other films have faded.

It’s been…

…a lot of fun doing these reviews. I’ve been participating in The Spoiler Warning off and on for years (I remember when Up In The Air was my #1, if that clues you in), but this is the first time I’ve let it be a weekly thing. As a frequently busy person, it’s been a wonderful excuse to take the occasional break and hit up the theatre. As an engineer, these write-ups have provided an often-absent creative outlet. And as a movie lover, I’m glad for the gems I never would have given a chance on my own. It’s been a great year for movies – here’s hoping 2015 is even better!

Of all my top choices, this is by far the one dearest to my heart; which also makes it the least likely to be universal. I was so blown away by my first viewing of Calvary

Of all my top choices, this is by far the one dearest to my heart; which also makes it the least likely to be universal. I was so blown away by my first viewing of Calvary  Inherent Vice is an inherently un-Stephen film. Like Anderson’s The Master, it eschews traditional narrative and emotional anchors outright: it had zero interest in holding my hand. But where I found The Master dry and distant, Inherent Vice was a joy to behold. With a distinct sense of time and place, unquestioning style, and a sprawling plot which would only be called “massive”, it left me in a daze. Phoenix is perfectly good as straight-man Doc, but it’s the zany characters in his orbit that really make the film: Martin Short as the drug-dealing dentist, Josh Brolin the repressed bully/manchild policeman, Katherine Waterston the ephemeral femme fatale, and MVP Joanna Newsom the remarkably warm narrator. It’s The Big Lebowki’s laid-back haze injected with Burn After Reading’s self-aware intensity: a period piece, a comedy, and a bizarre fever dream. There’s nothing quite like it.

Inherent Vice is an inherently un-Stephen film. Like Anderson’s The Master, it eschews traditional narrative and emotional anchors outright: it had zero interest in holding my hand. But where I found The Master dry and distant, Inherent Vice was a joy to behold. With a distinct sense of time and place, unquestioning style, and a sprawling plot which would only be called “massive”, it left me in a daze. Phoenix is perfectly good as straight-man Doc, but it’s the zany characters in his orbit that really make the film: Martin Short as the drug-dealing dentist, Josh Brolin the repressed bully/manchild policeman, Katherine Waterston the ephemeral femme fatale, and MVP Joanna Newsom the remarkably warm narrator. It’s The Big Lebowki’s laid-back haze injected with Burn After Reading’s self-aware intensity: a period piece, a comedy, and a bizarre fever dream. There’s nothing quite like it. This award is for films which were conventionally great: they didn’t break new ground in form or style, but were flawlessly executed from start to finish. The winner, Nightcrawler

This award is for films which were conventionally great: they didn’t break new ground in form or style, but were flawlessly executed from start to finish. The winner, Nightcrawler  This award is for comfortable, low-stakes films which, while not exceptionally daring, were pitch-perfect in their respective genre. With its distinctly New York vibe and infectious DIY aesthetic, Listen Up Philip was the clear winner: it took inherently unlikable characters and, somehow, created something charming, empathetic, and warm. While Jason Schwartzman was good as the titular Philip, the true scene-stealer was Elizabeth Moss, who blew me away in her own small, genuine way. Love Is Strange looked like it would be pure Oscar bait, but the leads (John Lithgow and Alfred Molina) were too convincing to ever feel precious: they conveyed a particular brand of loneliness (realizing you’ve become a burden on the people who love you) with ease and grace, and the New York it presents is a joy to get lost in. Grand Budapest Hotel

This award is for comfortable, low-stakes films which, while not exceptionally daring, were pitch-perfect in their respective genre. With its distinctly New York vibe and infectious DIY aesthetic, Listen Up Philip was the clear winner: it took inherently unlikable characters and, somehow, created something charming, empathetic, and warm. While Jason Schwartzman was good as the titular Philip, the true scene-stealer was Elizabeth Moss, who blew me away in her own small, genuine way. Love Is Strange looked like it would be pure Oscar bait, but the leads (John Lithgow and Alfred Molina) were too convincing to ever feel precious: they conveyed a particular brand of loneliness (realizing you’ve become a burden on the people who love you) with ease and grace, and the New York it presents is a joy to get lost in. Grand Budapest Hotel  If Whiplash hadn’t been my number 1 it would have handily won this award, reserved for small films which packed a disproportionately large, dizzying punch. As is, the honor goes to Starred Up

If Whiplash hadn’t been my number 1 it would have handily won this award, reserved for small films which packed a disproportionately large, dizzying punch. As is, the honor goes to Starred Up  There’s a distinct possibility that no one saw any of the movies I mentioned so far. That’s partly my own bias: smaller films tend to take bigger risks, and bigger risks often yield bigger payoffs. But this was also a great year for creative blockbusters, which have the difficult task of being both uncompromising and crowd-pleasing. They deserve all the love they’ve received, and then some. The winner, Edge of Tomorrow

There’s a distinct possibility that no one saw any of the movies I mentioned so far. That’s partly my own bias: smaller films tend to take bigger risks, and bigger risks often yield bigger payoffs. But this was also a great year for creative blockbusters, which have the difficult task of being both uncompromising and crowd-pleasing. They deserve all the love they’ve received, and then some. The winner, Edge of Tomorrow  This award (misleadingly named the “Charlie Kaufman Award” on the podcast) goes to a film whose central premise, while simple, was so fresh and thought-provoking that even if it had been sloppily executed, it would have stuck with me. The One I Love

This award (misleadingly named the “Charlie Kaufman Award” on the podcast) goes to a film whose central premise, while simple, was so fresh and thought-provoking that even if it had been sloppily executed, it would have stuck with me. The One I Love  It’s impossible for me to rank documentaries against works of fiction, as I learned with last year’s The Act Of Killing — it may have been the most striking thing I’d seen in years, but how could I possibly compare it against a romantic comedy? I can’t bring myself to try, but these three films could go head-to-head with the best of my list. The Missing Picture was a heartbreaking look at the Cambodian genocide under the Khmer Rouge. Like the eponymous Act of Killing and excellent Waltz With Bashir, its narrator used a creative outlet to share unfilmable memories: in this case, acting out the attrocities with small, hand-engraved figurines. Like those documentaries, it is both devastating and hopeful, its darkest scenes frequently intercut with gorgeous flights of fancy. It’s a story about the triumph of the human spirit, and it’s truly beautiful. On the other end of the spectrum, Jodorowsky’s Dune is by far the most fun I’ve had with a documentary in recent years. The film, which centers around a movie that never got made, is a joy to behold: it’s bizarre, visually stunning, and a celebration of the indomitable creative spirit. Perhaps the most surprising was Mistaken For Strangers, which ostensibly begins as a tour documentary but ends as a deeply personal look at jealousy and sibling dynamics. If you told me a documentary about The National would almost make me tear up, I’d probably laugh at you. But I’d be wrong. Life Itself didn’t quite reach those heights, but it came close: the chance to see Roger Ebert tell his own story, mere weeks before his passing, is a gift to the film community. As a work of art it was pretty modest, but as a tribute to a lost icon it’s essential.

It’s impossible for me to rank documentaries against works of fiction, as I learned with last year’s The Act Of Killing — it may have been the most striking thing I’d seen in years, but how could I possibly compare it against a romantic comedy? I can’t bring myself to try, but these three films could go head-to-head with the best of my list. The Missing Picture was a heartbreaking look at the Cambodian genocide under the Khmer Rouge. Like the eponymous Act of Killing and excellent Waltz With Bashir, its narrator used a creative outlet to share unfilmable memories: in this case, acting out the attrocities with small, hand-engraved figurines. Like those documentaries, it is both devastating and hopeful, its darkest scenes frequently intercut with gorgeous flights of fancy. It’s a story about the triumph of the human spirit, and it’s truly beautiful. On the other end of the spectrum, Jodorowsky’s Dune is by far the most fun I’ve had with a documentary in recent years. The film, which centers around a movie that never got made, is a joy to behold: it’s bizarre, visually stunning, and a celebration of the indomitable creative spirit. Perhaps the most surprising was Mistaken For Strangers, which ostensibly begins as a tour documentary but ends as a deeply personal look at jealousy and sibling dynamics. If you told me a documentary about The National would almost make me tear up, I’d probably laugh at you. But I’d be wrong. Life Itself didn’t quite reach those heights, but it came close: the chance to see Roger Ebert tell his own story, mere weeks before his passing, is a gift to the film community. As a work of art it was pretty modest, but as a tribute to a lost icon it’s essential. While they weren’t quite striking enough to rank, it’s worth mentioning that there were still plenty of movies which captured the intimate, “indie” spirit I normally gravitate towards. The winner, Frank

While they weren’t quite striking enough to rank, it’s worth mentioning that there were still plenty of movies which captured the intimate, “indie” spirit I normally gravitate towards. The winner, Frank  Sometimes I can respect a movie’s vision while not personally loving the outcome. With striking imagery and a haunting score, Under the Skin was likely the most stunning sensory experience of the year. The guerilla-style filmmaking and socially resonant topic (the male gaze, expectations on women) gives me huge respect for the creator. It left me a bit cold, but I can see myself loving it in a properly calibrated second watch. Runner up Only Lovers Left Alive gave a shot of originality to a done-to-death vampire genre, turning it into a stirring think piece about art and culture. While the pace was a little too slow to pull me in, in time I can see it lingering long after most of these other films have faded.

Sometimes I can respect a movie’s vision while not personally loving the outcome. With striking imagery and a haunting score, Under the Skin was likely the most stunning sensory experience of the year. The guerilla-style filmmaking and socially resonant topic (the male gaze, expectations on women) gives me huge respect for the creator. It left me a bit cold, but I can see myself loving it in a properly calibrated second watch. Runner up Only Lovers Left Alive gave a shot of originality to a done-to-death vampire genre, turning it into a stirring think piece about art and culture. While the pace was a little too slow to pull me in, in time I can see it lingering long after most of these other films have faded.